In his four-decade career, Don Simpson has seen it all. He found early success with his signature superhero parody character Megaton Man, had a front row seat to the indie boom of the ‘80s, and then rode the Image and self-publishing waves of the mid ‘90s. But then, only a short while later - there he was, behind the register at Borders, selling copies of his own work while being paid just above minimum wage. Simpson ultimately gave up on the comics industry and went back to school, resulting in a doctorate and a 10-year run in academia, before returning to a vastly different world of comics. All that sounds like a lot, but it barely scratches the surface of the life and times of Donald E. Simpson, PhD.

I sat down with Simpson over Zoom for a sprawling discussion about his roller coaster ride of a career. Get comfortable, because the guy has seen it all, and has a lot to say.

-Jason Bergman

* * *

Why don't we start at the very beginning? Do you remember the first comic you ever drew?

[Laughs] That I ever drew, you mean as a child?

Yeah.

Okay, well, I think I did a crayon version of Superman fighting a dinosaur that had a horn that shot rocks out of it. [Laughter] So this would be like 4 or 5 years old, and it would have been in crayon on lined paper. I think my mom helped me with the words. It was held together with butterfly clips, and yeah, that would be my first epic. I think there was one picture per page, but it was sequential. Some dinosaur comes out of a volcano and Superman comes and saves the day, beats him back. I think it was based on some Saturday morning cartoon. This would have been the mid ‘60s. ‘65, ‘66, something like that.

Do you remember the first time you drew something like Megaton Man?

Well, not Megaton Man particularly. I remember in kindergarten, you know, just drawing the basic house with the tree in the front yard and the family. And for some reason, other kids just found [drawing] boring or they wanted to play kickball or something. I remember finding at an early age that I could make the lines do what I wanted, and I got some kind of satisfaction from that. I found it very absorbing. My grandmother had one of these little notepads that was a roll of paper you would pull out and tear off, that you'd keep by the phone. One of my earliest drawings was just a pencil Superman. So that would be, again, maybe 5 years of age, 6 years of age.

I don't think I was exclusively interested in superheroes, but just anything arts and crafts I found absorbing from an early age. I got a sense of satisfaction whereas other kids I recall just found, especially from kindergarten through the early grades, they became increasingly frustrated with drawing and couldn't get the nose to look right or something. And so they gave up and went off and did other things.

When did Megaton Man come in?

Well, that was pretty late. That's after high school. There were a lot of characters that I had created in junior high school. Of course, I was reading Marvel Comics from the age of 10, summer of 1972. And I started mixing in my own characters. Some of those characters ended up in Bizarre Heroes.

Megaton Man was very close to when I got into comics. It was kind of the freshest thing at the time because I was roommates with Mike Kazaleh, who was an animator. He drew Captain Jack for Fantagraphics back in the day. Later he drew Ren & Stimpy comics for Marvel or DC or whoever had that license. We were roommates in Detroit, we were a couple of undiscovered geniuses.

So in the early ‘80s, indy publishers like Eclipse were starting to publish, and Fantagraphics was starting to publish Love and Rockets and Don Rosa’s Comics and Stories and Lloyd Llewellyn, and Dave Sim [had] you know, Aardvark-Vanaheim, which was expanding under Deni Loubert. So there was this quasi-underground, post-'ground-level' alternative thing going on. There was Heavy Metal and RAW magazine, and somewhere in there I wanted to fit in. I'd kind of given up on the work-for-hire Marvel penciler idea I’d had in high school.

Mike and I had this little rivalry about his funny animal animation and my dramatic superhero science-fiction tendencies, and we decided to kind of switch. So he tried to do superheroes for a few days, but gave up pretty quickly. I tried to do something funny and humorous, and it was a little gentleman’s bet that we had. I remember the first few things that I tried in the humorous vein were really treacly, sappy, kind of sub-Archie comic cutesy. I don't know what it was; it wasn't funny stuff, but I kept persisting at it. Finally, I remember drawing this beach bum, this kind of muscle beach bum draped with young bikini-clad ladies, and it got a laugh from Mike and my other roommate, Bryan Gabel, who was a filmmaker. I think Bryan's still working on his black & white film in Detroit some 40 years later. [Laughs] But that was the first thing that I drew that got a belly laugh from people.

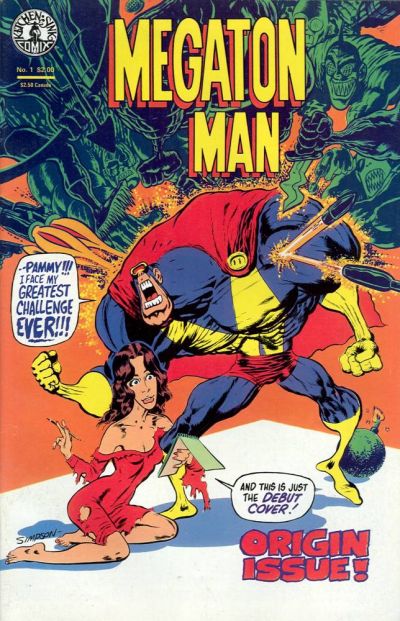

The name Megaton Man just completely crystallized the concept - it perfectly captured a certain political and cultural moment, as well as the Marvel Comics superhero, the hyper superhero, the post-Burne Hogarth Dynamic Anatomy superhero, the Arnold Schwarzenegger Conan physique. And from there, everything just gelled. The name was like that little speck in the middle of the snowflake that germinates, and everything around the concept emanated from that. So then I realized, he's basically a Superman parody, so he's going to work at a newspaper, and the newspaper we’d call "The Manhattan Project," and Megatropolis would be the city, etc., and all the different characters, everything just fell into place as a result of that name.

When you started, was the intention straight parody? Because, pretty quickly the series veers away from that classic Kurtzman-style satire.

Yeah, you know, people thought of it as a superhero satire that was discussing current events in the comics - that my target was the current industry. Of course, I went to comic book stores and I knew what was going on; eventually there'd be Secret Wars and Crisis and this and that. But I wasn't reading Marvel and DC comics. My references were all from when I was 10 years old in 1972 through maybe 1977. In my neighborhood, there was stuff dating back to the late ‘60s. A kid around the corner had a big stack of comics, and I could trade him two new comics for an old one. And that was how I got a Steranko Captain America and some Kirby Thors and things like that. And there were a lot of reprints going on in the mid ‘70s. That’s what I was drawing on for parody - certainly not the ‘80s scene, which I regarded as entirely derivative of that earlier period.

My frame of reference was the Silver Age, which to my mind goes up to the advent of the new X-Men. My influences were Kirby and Ditko and Steranko and Romita and Gil Kane and Joe Sinnott and Artie Simek, not the stuff that was being done in 1982-83, which would be Jim Shooter's era. At the time, I may have picked up a couple of John Byrne Fantastic Fours, but I thought they were weak tea compared to the stuff I had read as a youngster. The Silver Age was formative, not the ‘80s.

That’s the era I grew up with. Don’t get me wrong, I love the Lee/Kirby Fantastic Fours, but I’ll always love that Byrne run.

I can see that, but I see deficiencies in his draftsmanship. Same with George Pérez, and really that whole generation that came after Kirby, Romita, Buscema, Kane. To me, they were the workhorses; that was textbook superhero cartooning. That generation could do it all.

Anyway, the point being that by the '80s, I wasn't really interested in current stuff. They were all doing the same thing anyway. I mean, they were all just essentially repeating the Silver Age, remixing and redistributing, moving the chess pieces around, as Larry Marder would say. That's what John Byrne was really great at, moving the pieces around and making it seem brand new, I guess.

But was your intention then to parody those comics you grew up with? Because again, you went for plot, not necessarily straight humor. Maybe the very first issue [of Megaton Man, Kitchen Sink, Nov. 1984] is kind of a gag issue, but then you quickly go off in a different direction.

Yeah, and keep in mind there was already Jim Valentino doing Normalman, which beat me to the market by half a year, a year almost. Normalman was coming out from Aardvark-Vanaheim, and in fact I have a rejection letter from Dave telling me, “Sorry, we're already doing one parody book - but good luck.” Of course, Jim was doing something very different from me in terms of parody - he was very focused on the then-current industry, whereas I was not at all. In any case, I soon ran out of stuff to make fun of.

I did things like Megaton Man getting a black suit for one panel - a reference to Secret Wars. That's as deep as I went into referring to anything going on in the ‘80s with Marvel or DC. I remember I had a copy of Fantastic Four #73 - I know that because I cut out the numbering and the comics code seal and used it on the artwork for Megaton Man #1 for one of the fake covers inside, no doubt destroying a priceless book now. Those were my references. I had some old comics from the mid ‘60s through the early ‘70s, and, you know, The Steranko History of Comics and that kind of thing. But after two issues of Megaton Man, I ran out of stuff to say.

Probably the worst advice I ever got at the time was from Denis Kitchen. “Now that you're in the business, you should subscribe to Comics Buyer's Guide,” he told me. The Buyer's Guide and The Comics Journal. I was already reading The Comics Journal before I had broken into the business - you know, you read The Comics Journal because it was a kind of a support group in those days. If you outgrew superheroes and you didn't know what to do with yourself, you read The Comics Journal and you read about how Jan Strnad had been abused at Marvel and so on. Every disillusioned mainstream professional would come to The Comics Journal and talk about how horrible it was working in the industry. So I was reading The Comics Journal already, and then I subscribed to Comics Buyer's Guide, which was like subscribing to a Catholic school newsletter or something, which would be very depressing to read. I tried to read CBG cover-to-cover every week and try to get something out of it, but there was just nothing of any thoughtful substance. At least The Comics Journal had something to think about and evaluate. But the Buyer's Guide was horrendous. That was the worst advice I ever got. It was depressing, trying to keep up with news about the comics industry.

Was it depressing because you didn't you didn't see yourself or your work reflected in it?

Yeah. And it only got worse. I remember in the late ‘90s-- I was out of the business at that point, and I remember looking at a Diamond Previews catalog, and I literally was sick for three days. It had a catastrophic, depressing effect on my metabolism. There was nothing going on in the industry that I could identify with.

We’ll get to that, but I want to talk a bit more about your early era, because Megaton Man predated the reinvention of the superhero. You touched on some of the exact same themes that would come up later in the work of Frank Miller and Alan Moore, and that whole dark, or “realistic” wave that’s credited with reinventing the genre. You were already doing that three, four years earlier.

It will take an historian to figure out the exact timeline, but I agree. You were talking about how I parodied the superhero genre in Megaton Man, but then the plot took on a life of its own, and the characters took over. That was just because I had nothing else to do. I mean, I intended Megaton Man #1 to be a one-shot. I'd sent it to 15 different publishers, including Fantagraphics. I got a couple nice long letters from Gary Groth saying, “Stop aping superheroes, then maybe we'll publish you at some point.”

It took me 13 months to do the first issue. Then Denis Kitchen said, “Can you do this every other month?” I didn't know what the hell I was doing, but I said, “Sure!” I had done no world-building, I had no characters apart from parodies and pastiches, I had no plot in mind, I had no 300-issue plan like Dave Sim. I just figured, “Well, they’re giving me a chance to do this; I'm gonna try to do it.” I remember it was the spring of '84. I had finished the first issue and sent off photocopies to 15 different publishers, and I got all these rejection letters from Eclipse, from Epic Illustrated and everywhere else, but Denis Kitchen wanted to publish this thing, and he wanted me to do it as a series.

Now, in recent years, I've kind of figured out why in the world he would give a beginner such an opportunity - it was because he needed a plausible color comic. He needed a line of color comics, in fact. He had been forced by fate to do The Spirit in color [beginning in 1983]. I don't think he really wanted to do The Spirit in color, but there was this Will Eisner story called John Law Detective which Eisner had created and had later repurposed as a Spirit story, perhaps the most famous Spirit story. But the original version of it was the Spirit but without a mask - John Law had an eye patch, instead. Eisner had kept stats of the original version, and apparently it wasn't covered by the Kitchen Sink contract. Cat Yronwode and Eclipse offered to publish it in color. Eisner first offered it to Denis, and Denis said “I really don't want to do color comics.” He had been a black & white underground publisher, and the economics of color printing were very, very different - it was even worse than today. Very, very risky, very expensive, and very prohibitive. So Denis passed on John Law Detective in color, and Cat Yronwode [and] Eclipse released it. They sold, I want to say, 75,000 copies, which was like a king’s ransom in those days. And after that, it didn’t take much to figure that Denis was gonna have to do The Spirit in color from now on if he wanted to hold onto Eisner. I don't think Eisner was the kind of guy who had to raise his voice or stomp his feet; I think Denis just kind of knew.

And so The Spirit was in color for about a year, and Denis realized he needed more titles so that he could go to these color printers and say, “Can you bring the unit price down, because I'm gonna be doing more volume,” that kind of thing. He eventually did Death Rattle in color after Megaton Man, which had been an old underground horror anthology about 10 years earlier. He tried a two-issue Harold Hedd series by Rand Holmes called Harold Hedd in Hitler’s Cocaine. Rand Holmes was an underground cartoonist, a very talented guy, who did like a Wally Wood/Will Eisner fusion. Harold was bisexual, an old hippie, and he and his sidekick somehow stumble onto der Fuehrer's stash of blow - just what the Direct Market was asking for. Not surprisingly, it was a complete bomb in color. I remember unopened boxes of it in the Kitchen Sink warehouse when I lived at Kitchen Sink Press. I stacked three boxes of Harold Hedd #2 and sat my little portable black & white TV on top of them near my drawing board in what served as the bullpen. I remember when the space shuttle Challenger blew up; I had just turned on the portable TV one day, and it was sitting on top of those boxes of Harold Hedd #2. That’s how much of a commercial disaster that had been. Somehow, the Direct Market wasn’t quite ready for a full-color, R-rated underground comic about Nazi drugs!

So that was kind of a false start for Denis in creating a viable color comics line after The Spirit. And just at that moment, my Megaton Man #1 photocopies came over the transom. I was 23 years old, I had never written and drawn a comic series before, it was the first comic I’d ever created. I regarded it as a kind of “masterpiece,” in the old sense of a sample that demonstrates a certain mastery. I thought I might get some lettering work from it at best. Meanwhile, Kitchen Sink Press had never published a new, ongoing series with anybody writing and drawing, at least not on a bimonthly frequency - I think Crumb had managed four issues of Mr. Natural over a 12-year period or something. But they gave me a shot, which is just insane to think about now. And the worst part of it was they were very hands-off. They were like, “Just do what you want.” Dave Schreiner was a great editor to bounce ideas off of, but they weren’t set up to groom young talent; it wasn't a very structured environment.

So I had to find my own way. That first summer I was still living in Detroit, and after signing the contract I sent off the original artwork for the first issue. Trying to do the second issue all summer long, I was just a mess. I ended up doing all these dream sequences and flashbacks and a very convoluted storyline, trying to figure out how I could top that first breakthrough issue. And it was just a mess. I accumulated something like 64 pages of material, all disjointed and incoherent, some of it inked, some of it not inked. I was at the end of my rope; I remember photocopying it all in desperation and sending it off to Wisconsin to Denis and Dave to try to sort out. They didn't know what to make of it. Luckily, during all this time, they were looking for a new printer, so the first issue of Megaton Man was delayed until the fall, and then it was delayed again, almost until December. At the end of the summer of '84, I took a long walk around the New Center area of Detroit, which was where the GM Building and the Fisher Building were located. It was a really long walk - three miles, four miles, maybe five miles, past the campus of Wayne State University and back. It was a nice summer day. By the time I got back home, I had the idea for the second issue of Megaton Man—with Megaton Man joining the Megatropolis Quartet—which I drew in about six weeks.

After the second issue was in the can, I took that 64 pages and broke off a few chunks, and incorporated those into issues #3 and #4. So, there are these flashback sequences with Bad Guy and dream sequences about the End of the World and so forth - those were cannibalized from that 64-page false start from the summer of 1984. But the second issue, it hit me like a bolt of lightning to just have Megaton Man join the Megatropolis Quartet, because See-Thru Girl had left at the end of #1, and they needed a fourth character. So Megaton Man became Captain Megaton Man, and we were off and running for the series. But as you say, the characters started to take over, and I didn't even realize it. Dave Schreiner recognized it before I did. I thought I was somehow obligated to do a parody of superheroes for the rest of my life - I was supposed to comment on the industry and I was supposed to be funny in every panel and that kind of thing. But Dave was the one who said, “You know, you’ve got some interesting characters here - none of them are particularly likable except Megaton Man, who's trying to do the right thing.” He thought Pamela Jointly was insufferable and everybody else was very self-centered and self-seeking. He said, “You know, you've got original characters and storylines in their own right, and you should just follow that instead of trying to do this formula that you have in your mind of a superhero parody.” It took a long time for that to really sink in, but he was right. He passed away many years ago now, but Dave was the guy who recognized that Megaton Man was actually a character-driven series. Even though the popular perception of it was Not Brand Echh, that I was spoofing superheroes. Even Denis thought that. Denis was like, you know, “Just have fight scenes - and parody the Punisher movie or something.”

It seems like issue #5 was kind of the turning point, right? That's the See-Thru Girl issue.

I’m glad to hear you say that. I've always been very proud of that issue. That was the first issue I did when I moved to Wisconsin, and yeah, that is a unique issue, because it's all about See-Thru Girl, it’s the world of hyper-masculine superheroes from the female point of view. It's in the first-person, it's her reflecting back on her crazy life. She obviously started out as a parody of the Invisible Girl from the Fantastic Four, who was kind of a wallflower, eye candy. She’s the girl who's literally invisible, whose powers are not really that much use in a fight scene. And my take on it was, you know, she's married to the mad scientist of the group, who's much older, like three times her age - so what is that marriage like? That's just where my imagination went. Like, what would this really be like? And at the end of the first issue, she's having this surreptitious love affair with Megaton Man. It's like Superman crosses over with the Fantastic Four and he hooks up with the Invisible Girl, only they’re my avatars - the See-Thru Girl hooking up with Megaton Man. By the end of the first issue, she and Pamela Jointly, who's the controversial columnist, get fed up hanging around Megatropolis with these toxic-masculine types, so the gals take off to hit the road. That in itself was a genre of the ‘60s and ‘70s, hitting the road, go see America - Route 66, the TV show, or Easy Rider or The Graduate or whatever. Go see America! And they end up back in Ann Arbor. It was just a funny way to end the first issue, to have both of Megaton Man’s love interests leave the city, to write themselves out of the series. But I had no follow-up to that. I had no idea. It was just a funny way to end the one-shot. When it came time to continue the series, I thought, “Well, what would happen after Stella and Pammy left? What happens next?” That’s always the way I’ve plotted all of my stories.

Well, the girls would be off in Ann Arbor; Megaton Man would be back in Megatropolis, and he would join the Quartet, and that would wreak all kinds of mischief. I don't know how I thought of issue #5, which is entirely a flashback, except that I had this hanging plot thread. So, the entire issue is a flashback of their relationship, the See-Thru Girl and Megaton Man’s extramarital affair. In issue #4, I show them going on patrol—they hook up on top of a skyscraper somewhere—and I think, “All right, well, that's funny.” It’s another absurd idea, like having the women leave at the end of issue #1. But after the initial shock of the joke, I’m left thinking how I can develop it - what are the consequences for these characters? It’s funny, but it’s funny because it’s serious - it has human consequences.

The affair between Megaton Man and the See-Thru Girl—Trent and Stella—explains the conflict between Rex Rigid, the older mad scientist member of the Quartet, and Megaton Man. There's this friction between them in the second issue because Rex knows something's been going on with his young trophy wife and this nuclear-powered hero who just popped in from another dimension. After that, it occurred to me, “What if Stella realizes that she's pregnant now, and she's in Ann Arbor and the father of her child, Megaton Man, is back in New York?” The great thing about creating comics is that you think up these ideas, but then it takes you several weeks to draw them, and hopefully by the end of the time it takes to draw it, you'll have more ideas for the next issue. But I was just making it up as I went along; I had no multi-issue story arc or anything like that in mind. I was not a capacious plotter of storylines.

Speaking of capacious plotters, around this time I guess you were introduced to Alan Moore, because that's when In Pictopia was produced. Around the mid ‘80s?

I talk about this in the Afterword of my latest publication, X-Amount of Comics. So, in issue #6 of Megaton Man, I did a little Swamp Thing parody. Megaton Man, not only is he a reporter at the newspaper, but when Pamela Jointly leaves town, he becomes the new controversial columnist, the replacement for Pammy’s old job. And the controversial columnist’s job is to criticize Megaton Man. But there's a running gag where whenever he needs to go out and be Megaton Man, he pulls this sawdust dummy out of the closet and has him sitting at his desk in the newsroom, and nobody can tell the difference. So I have this whole scenario where the bad guys are trying to kill Megaton Man, and of course, everybody knows his secret identity, because he can never hide all that bulk under his suit. Besides, he wears his cowl and goggles under his hat. So the bad guys end up assassinating the sawdust dummy, and the dummy gets thrown from a plane into the Florida Everglades after it’s been doused in Megasoldier Syrup.

I’d been more of a Man-Thing fan myself in the ‘70s. I had seen a few issues of Bernie Wrightson’s Swamp Thing with Len Wein. But I was more of a Ted Sallis fan, for whatever reason. I was induced to read Swamp Thing by Norm Harris, who ran The Eye of Agamotto comic shop in Ann Arbor - he actually loaned me a stack of comics to read, which he circulated like a lending library, for exactly that purpose, to proselytize for Swamp Thing. So, one of the few mainstream comics of the ‘80s that I read was Swamp Thing - the Alan Moore Swamp Thing with Steve Bissette and John Totleben.

Not long after, Steve Bissette and John Totleben came to Pittsburgh, and I got to see them at a small show. I just showed up as a fan, and I think I probably had two issues of Megaton Man of my own out by that point. So, I got to meet them, and they were very friendly. This was before they really became like rock stars - they were the first Americans to draw Alan Moore, and they had the aura of the Beatles. So I got to meet these guys, and Swamp Thing was the first thing that I'd read of Alan Moore's.

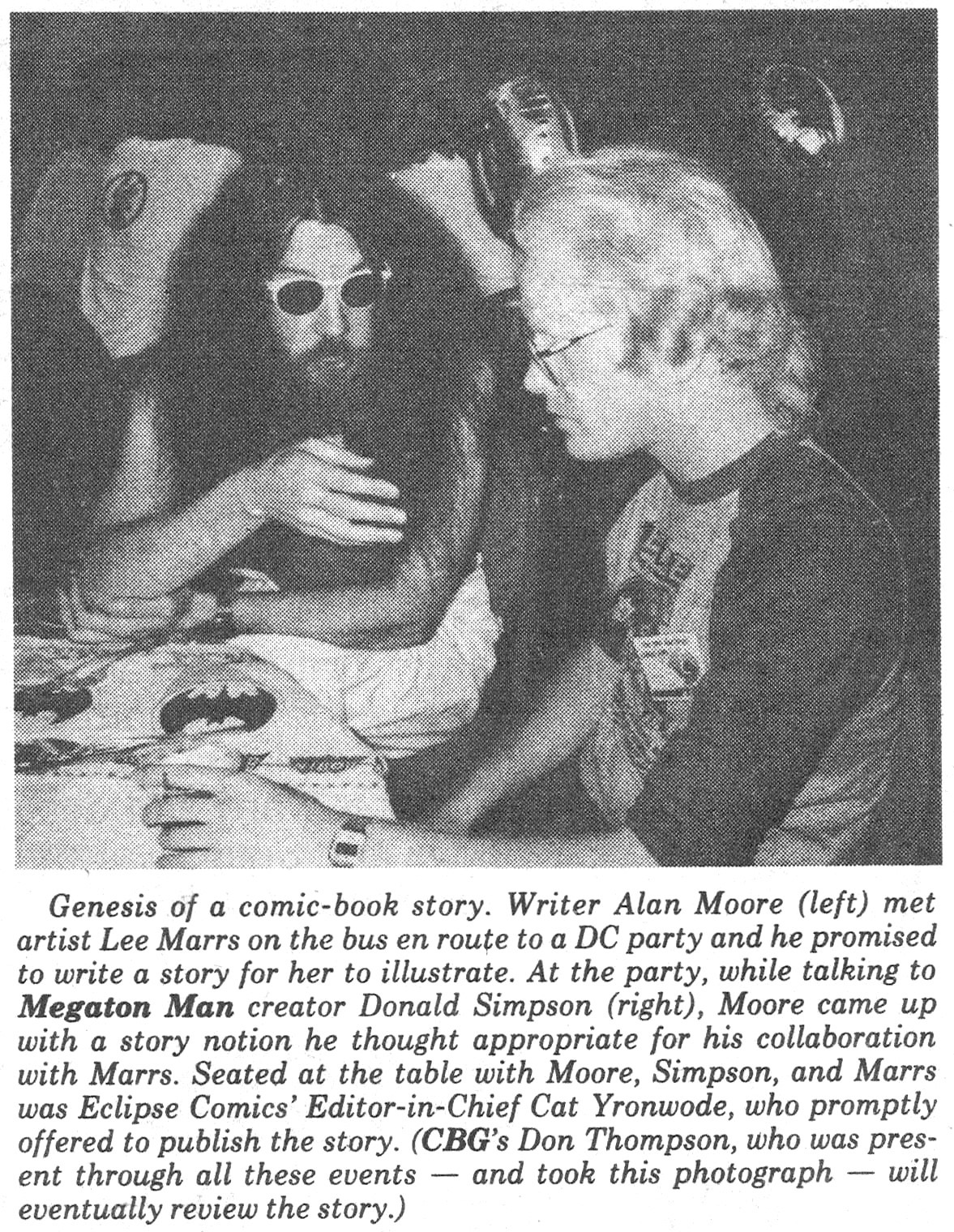

So, I did this parody of Swamp Thing in #6. I went to San Diego that year—this would have been ‘85—and I had photocopies of Megaton Man #6 in my little portfolio. At the same time, Eclipse had brought Alan over for the American debut of Miracleman. And I think I just ran into him in the dealer’s room. He was easy to spot. You know, he's walking around, like 6 or 8 or maybe 18 people are following him around the convention. This was back in the very early days of the San Diego Comic-Con, before it became monstrously huge. I stopped and introduced myself, and I had these photocopies in my portfolio. I showed him the page. I said, “I’m doing a Swamp Thing parody.” He knew who I was, and he read the last panel out loud, where I had parodied his “Anatomy Lesson” dialog. “But he’s not Trent Phloog… he never was Trent Phloog… he never will be Trent Phloog,” or however it goes, this sawdust dummy that is now slogging through a swamp. And Alan reads it and he goes, “Oh, this is brilliant writing. Just brilliant!”

Later that evening, DC had a gathering down by the marina; I remember taking a bus from the convention to the party. DC editor Julie Schwartz was chasing the Wonder Woman model around the bus, and she’s changed out of her costume for the evening, and she’s waving her star panties around. When we got to the marina, [Don] Thompson from the Buyer's Guide took a photo of me sitting next to Alan at a table with the tiki candles and the whole bit, and I look like I'm 14 years old next to Alan, who looked like an old hippie even though he was maybe a decade older than me. I mean, I just look so dumb and naive in that photo, and they run it in the CBG - I'm in the business for like five minutes, and I'm chatting with Alan Moore. And I wasn't like totally star-worshiping or gushing or anything, it was just a nice confab, and we were conferring.

And at one point he says to me, “You know, I'm ripping off Megaton Man - but not really.” I said, “What do you mean?” He says, “Well I'm doing this Watchmen thing, and I've got this character called Doctor Manhattan; he's kind of a nuclear character, and, well, you'll see it's not really a total swipe, but it's kind of… you know.” And so I thought, okay, well, great. I’ll look forward to that. And sure enough, when Watchmen comes out, it's pretty clear that he was looking at Megaton Man even before I had shown him my Swamp Thing parody - he had been tuned into Megaton Man from the beginning, apparently, among other American alternative comics. I suppose in those days I regarded it as flattering; I thought it was like, well, we're kind of mutually riffing on each other. Alan certainly had a much higher profile at DC, but this was before The Killing Joke and before the last Superman story he wrote before John Byrne turned back the odometer. Alan might have done Michael T. Gilbert’s Mr. Monster [#3] by that time, but the few things I read of his - I mean, they were all rich and entertaining and imaginative. And sure enough, when Watchmen #4 came out, there's Doctor Manhattan and-- what's her name, Nightshade or--

Silk Spectre?

Silk Spectre. I always get that confused.

Doctor Manhattan and Silk Spectre literally go on patrol in Watchmen #4 just like Megaton Man and See-Thru Girl went on patrol in Megaton Man #4, and Dave Gibbons drew the skyscrapers just the way I drew the skyscrapers in my comic, which is like a crossword puzzle pattern or something. And it was pretty clear Alan had been kind of cribbing.1 But there was just this feeling - oh well, you know, it's a kind of a shared discourse, a mutual admiration society; we're colleagues. That was the way I felt at the time. And I felt that way again later, in the ‘90s, when everybody was doing their own self-contained universes. I was doing Bizarre Heroes and Alan and Rick and Steve were doing 1963, and Rick Veitch later did Brat Pack, and Kurt Busiek did Astro City. Gary Carlson and Chris Ecker were doing the same thing with Big Bang Comics. Everybody was doing a universe in the ‘90s, so that was almost 10 years later, and again it felt collegial, like we were all working in a similar vein. We were fellow travelers, as it were. Those were the good old days.

So, how did In Pictopia come about, then?

That's a good question. You know the whole story of Harlan Ellison being interviewed by Gary Groth in The Comics Journal, and talking about Michael Fleisher,2 and in glowing terms Harlan Ellison said that Michael Fleisher’s scripting of Jonah Hex was “bugfuck” - which for Harlan was the sincerest form of flattery. Harlan meant it was really twisted, it was sick, it was dark. But Michael Fleisher thought it was very insulting, and sued Ellison and The Comics Journal for defamation. It became an opportunity, a cause célèbre, for the industry, which hated the Journal because it had been a thorn in their side for years, criticizing work-for-hire and superheroes and corporate hackwork and all. Because they were bringing all kinds of highfalutin criteria to their medium, calling it an artform. All sorts of people were lining up to testify on behalf of Michael Fleisher; Jim Shooter testified against the Journal and so forth. Fantagraphics ran up huge legal fees, so Gary and Kim Thompson put out a series called Anything Goes! as a fundraiser. Cartoonists would contribute work and all proceeds would go to defray their legal costs. And somehow, Alan Moore was prevailed upon to contribute a story. I don't know how that happened as far as Gary’s end. There was another artist that was going to draw it, but whoever was going to be the artist, that fell through, and it came to me. I was probably doing Megaton Man #7 or #8, so that would be like early ‘86. I got this script, and it was for an eight-pager, but it was really dense. Somehow Gary intuited that I would be able to bring this off, and I drafted Pete Poplaski to pencil the newspaper comic strip scene, which is like a page and a third. And I got Mike Kazaleh, my old roommate, to do the funny animal ghetto, which is a scene, also a page and a third. And I penciled the rest and inked and lettered the whole thing - but I had to expand it to 13 pages because there was so much in the script. Gary didn’t seem to mind - he was filling five more pages for free!

Pictopia is this place where comic book, comic strip, and animation characters all live in the same city, and they're all on hard times except for the superheroes, which are becoming increasingly grim and gritty and juiced up. The superheroes are in color, everybody else is in black & white or in yellowed newsprint. And it really worked. This was before Who Framed Roger Rabbit, the Disney movie, entertained a similar idea of mashing everything together like that. And it's really an allegory of how corporations are taking over everything.

There’s a group of leather-clad new superheroes, really sexed-up and thuggish - people have seen in this a certain foreshadowing of Image Comics, but of course, it was already happening with X-Men and Teen Titans and Punisher and Vigilante, and prior to that, with Judge Dredd. Which is why it’s so amusing now to see Alan complain to the UK press that superheroes are fascist, as if he just discovered that. He satirized it 35 years before!

Anyway, there are bulldozers coming at the end of the story, and people are disappearing, being replaced with new, revamped versions. You know, the old favorite comic book characters - there's a Plastic Man kind of character, Flexible Flynn, who disappears, and a Blondie-type housewife character who’s turned to prostitution; she disappears, and there's an ominous, fatalistic tone to the whole thing.

What few people realize is that Alan wrote a follow-up called Convention Tension, which would have been maybe a three-issue series or a six-issue series. This is before we thought in terms of graphic novels or collections; we were still thinking of series, either limited or open-ended. It would have been the counterpart to In Pictopia, which is an allegory about the fictional characters living in a city, and the impact of corporatization on their lives, although we never see anything but bulldozers and updated superheroes. Convention Tension, on the other hand, would have been about the industry - about the fans and the creators and the corporations running the show in a more literal way. It was directly about a hotel - I imagined it as being like Chicago Comicon at the old Ramada O'Hare in Rosemont in Chicago, where the entire industry gathers in one airport hotel for one nightmarish weekend. It was definitely a black comedy, as was In Pictopia, but in more realistic terms. In Convention Tension, there's a big dealers room, an Artists Alley, and all these characters. There's a Stan Lee character who's actually dead, who’s been cryogenically frozen; his capsule is up in a hotel room somewhere - because some insane editor felt the need to bring it along, although it’s an industry secret that he’s been dead for years. This was during the time when Stan was never seen at cons; he was busy running up his expense account in Hollywood or whatever. And there's a Jack Kirby character who resents the Stan Lee character and has a nervous breakdown when he realizes Stan’s been dead for years and he’s held a grudge toward a ghost, and there's a fan who gets stuck on an elevator for the whole convention; he never gets off on the right floor. After a while, he starts making up continuities about all the people he sees getting on and off the elevator. And there's a writer named Byron Starkwinter, who was pretty clearly a Steve Gerber parody. Byron Starkwinter is this young guy who writes mainstream superhero comics and he accidentally creates a character called Mookie the Worm which becomes a phenomenal hit, very much like Howard the Duck in the mid ‘70s. Byron can’t handle the sudden fame and fan adulation, so he takes a lot of drugs and goes crazy - little did we know this would be Alan’s self-fulfilling prophecy for his own career.

Convention Tension was only a plot outline, and like In Pictopia had been intended for another artist - perhaps Gary Kwapisz, who drew Conan. I wouldn’t have had time to commit to a multi-issue series, but I read this thing, and it made an impact on me. Nobody's seen it, because Anything Goes! came to an end, like all good things. The Fleisher lawsuit was thrown out and I guess Fantagraphics survived after paying off the lawyers!

So, any plans for that series were just dropped?

Yeah, it was never mentioned again.3 It would have been a pretty steep commitment to do a three-issue thing for free, and then Alan was already in the middle of Watchmen, and everything that followed after that. I was doing Megaton Man, then Border Worlds, but Convention Tension stayed in my files. But I've always thought of the Byron Starkwinter character, who greatly influenced Paul Nabisco, which was my satire of Steve Gerber with more than a passing resemblance to Alan Moore. I mention Byron in X-Amount of Comics, but I forgot to explain the reference in the endnotes - a major Freudian slip!

So you went back to Megaton Man, and started Border Worlds as a backup serial [in Megaton Man #6-10], and then spun that out into its own series.

Yeah. Now, as I mentioned before, I realized Denis really didn't like publishing color comics. It

was precarious, and the profit margins were tricky. There was Megaton Man, there was The Spirit in color, there was Death Rattle in color, for maybe two years or so. Three titles, and Megaton Man was the only consistently profitable Kitchen title in the Direct Market, naturally because it was a superhero parody. Death Rattle was kind of a tough sell. It was a spooky, R-rated suspense book, generally a horror title, but not quite as violent and gruesome as the old EC material. Frankly, I thought color worked against it - spookiness just seems to work better in black & white. As I mentioned, The Spirit had started out profitable in color, but then sales dropped. And the day came, around issue #9 of Megaton Man-- I was living in Wisconsin at the time, right there at the barn-turned-office, and Denis called us all into his office, [editor] Dave Schreiner, [art director] Pete Poplaski and myself. And Denis said, “Okay, well, we got to pull the plug on this color comic thing.” And he asked me, “What do you want to do? Do you want to continue doing Megaton Man?” And at that point we had already announced in a preview issue of Amazing Heroes, which was the old sister publication of The Comics Journal, that Megaton Man was going to end at #12, because I was running out of ideas. I was already doing Border Worlds as a back-up feature in Megaton Man, and I already considered that the follow-up to Megaton Man. When that meeting came about, I said, “Why don't we just wrap Megaton Man up with #10?” I'd kind of figured out what I was going to do for the final few issues, and I thought, “Well, I can compress the story without any loss, because I haven't drawn anything yet.” I hadn't written or drawn anything, so it would probably be better just to end it with #10 instead of having the last three issues be in black & white. So I got Denis to commit to extending the color line an extra month so I could wrap up the first ten issues of Megaton Man in color.

Border Worlds seemed to lend itself to a black & white treatment because it was going to be more serious and dramatic, more design-oriented - a lot of shadows and lighting effects and star fields and so forth. I think I had in mind a kind of European art cinema treatment, like Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville crossed with Woody Allen’s cinemascope Manhattan, but with all the special effects of a Ralph McQuarrie [Star Wars] movie. So I thought, “Let's just do Border Worlds as a black & white.” And that ended up being part of a line. Death Rattle then was in black & white, Alien Fire [by] Eric Vincent and Anthony Smith was also in black & white, and I did Border Worlds, the series, accordingly. Cadillacs and Dinosaurs [i.e., Xenozoic Tales] came in at some point. Now, suddenly, Kitchen Sink had this new identity as a black & white publisher - a more mature, EC science fiction kind of vibe going on, instead of what had gone before. The Spirit, of course, reverted to black & white as well - the whole line had a more somber, sober tone. And I did Border Worlds like that for seven issues [1986-87].

Now when we started, there was the black & white boom. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles had been in black & white, which became a self-publishing phenomenon a year or two before Megaton Man came into the market. Now everybody seemed to be scoring big with black & white comics. Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters was selling fifty, a hundred thousand copies; Paul Fricke and Scott Beaderstadt did a thing called Trollords that was selling thirty, forty, sixty thousand. Everything in black & white seemed to be going gangbusters. And Border Worlds started out pretty well - I was making more of a royalty off of it than on Megaton Man because I wasn’t paying for the coloring, and it was a 2% higher royalty to begin with, 10% instead of 8%. So I was suddenly making relatively big bucks!

I moved out to California, not far from where Gary and Kim and Fantagraphics were in Thousand Oaks - I remember [then-Amazing Heroes managing editor] Mark Waid shooting pool on a table set up in the garage-warehouse. And I stayed with Mike Kazaleh for a few months in Van Nuys. I ended up taking over Mike’s apartment when he moved to another place. So I moved out to California, and I was making enough to live on, but then sales started dropping like a rock. Part of it, I think, was the abrupt change from Megaton Man to Border Worlds - going from a superhero parody, a full-color funnybook to my attempt to be more serious, to play Hamlet. And just then the black & white bust, which was pretty evident by the fall of ‘86.

Border Worlds is still your only dabbling in that style. Have you ever thought about going back to something like that?

You mean the heavy shadows, the hardware and the science fiction?

Yeah!

Yeah, for sure. At least the extant seven issues—actually eight, with Marooned #1 [Kitchen Sink, 1990]—have been collected. More recently, I did a new ending chapter. Dover did a nice hardcover in 2017. It actually represents about half the story that I had in mind. At that point in my career, the late ‘80s, I had been in the business for more than five minutes and I was starting to think longer-term in terms of storylines; I was trying to plan out larger arcs over several issues. We still had no conception of graphic novels as such; we were still going month to month. I was just trying to keep the issues coming out every other month, but I was definitely attempting a longer, serialized story instead of just making it up as I went, like I had with Megaton Man.

But as far as returning to that style or returning to that dramatic look now… all I can say is, it was very painful when I had to stop doing Border Worlds. I remember being very traumatized by that. And that was when I turned to freelance. And luckily, in terms of paying my rent, Mike Gold was looking for artists for this thing called Wasteland for DC, and that started my freelance career. Which, I have to say, I didn't find enjoyable at first. Because up to that point, I had been only illustrating my own ideas. Except for In Pictopia, which was a full script by Alan Moore. And if you ever read an Alan Moore script, it's like it becomes your idea, because it's so dense and he explains everything that he wants - and then it's up to you to draw it. But illustrating other people's ideas didn’t come naturally to me. Most comics scripts, I soon discovered, tended to be more like recipes. Very, very schematic, very minimal. And you really have no idea beforehand what you’re baking. Wasteland in particular was very sparse. Del Close and John Ostrander, the authors, came from a background of theater - and not only that, improvisational theater. So, I think their ideal was a very minimal premise and not a great deal of instruction for the artist. Which would have been great for a certain kind of artist who has a lot to bring to the collaboration. But I was even more at sea than when I was floundering with the second issue of Megaton Man. I had met John, [cartoonist] Bill Loebs and I had even visited his house in Chicago, but I didn’t meet Del until years later. I’m sure if it had occurred to me to call them up and ask, “What’s my motivation in this scene?” they’d have been willing to coach me, because they were both a couple of practiced stage directors, literally. But it never occurred to me to ask - I thought I was supposed to just know this stuff because DC hired me.

Not only that, but Wasteland in particular was a series of curveballs - you never knew what you were going to get issue-to-issue. And I just had no method to approach ideas that I hadn’t thought up myself. I had no idea how to get into a script, no idea how to approach it, break it down. I learned. I think I learned and got better as the series progressed, but the first few issues were really rough going. Nowadays, I know how to approach a script; there’s a certain procedure. But back then, I had nothing. And I was too stupid to ask questions. Then I started doing Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and various other things.

So I started doing a freelance career of illustrating and I got the hang of it. And I ended up learning a lot from working with different writers and editors. I forget what your original question was.

I had asked if you’d ever thought about going back to that style, like Border Worlds.

Like I said, it was such a culture shock, and it was such a shift, and it was such a trauma, having to put that series aside and take on freelance work-for-hire. Years later, when Image was going gangbusters, Charles Brownstein, who was with the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, and Jim Valentino, contacted me. I don't remember exactly when this was, this had to be after Splitting Image! and Savage Dragon. And they asked me if I wanted to do Border Worlds for Shadowline, which was Jim's imprint at Image. Jim was looking for alternative kinds of stuff, non-superhero stuff -much like he later brought to Image in general when he assumed the role of publisher. And it was a very tempting opportunity for a number of reasons. I can't remember what all I was involved with that prevented me, but I was partially just gun-shy that I might not be able to pay the rent for the couple of years required to draw the second half of the story, and having to kill it again. I mean, if I couldn't be sure of at least a minimal income for two, three years, it would mean having to abandon it again, or put it on hiatus again. Which I just couldn't imagine. So I let that opportunity pass by. But aside from that and aside from returning to the character Jenny, the protagonist, for that final chapter [for the 2017 Dover collection], I have not seriously contemplated returning to Border Worlds -at least as a comic book series.

I think I would entertain the idea of attempting prose, although that's a whole different ball game, prose science fiction. It's a question of what the market will support. When I self-published Bizarre Heroes, that was something more of a compromise. It was something that I could live with, something that captured my imagination. It wasn't exactly Megaton Man, and it certainly wasn’t Border Worlds, but it was something that I felt was viable in the marketplace of the ‘90s, after I made a big pile of money at Image. [Laughs] Now such considerations seem irrelevant - I could do anything I want now and it doesn’t matter, it's not gonna make any money anyway! We’re past the age of print. Nobody knows how to monetize cartooning right now anyway. So I may as well be thinking about Border Worlds.

Getting back to the timeline, after Border Worlds, the industry contracted, and along came Anton Drek.

Well, in the late ‘80s I was freelancing. I had these red tag folders, three or four of them, and I had Bizarre Heroes #1, which was more the kind of thing I was doing in junior high school, kind of a serious superhero idea. Then I had Pteranoman #1, and I had the next issue of Border Worlds which became Marooned #1, which was the adults-only issue, the eighth issue that came out in 1990, a couple years after #7. And then there was another folder which was like Spider-Man samples or something. For some reason I was using folders to keep all these different projects together. As time permitted, I would do like a few pages of this, a few pages of that, but they all eventually came out. Bizarre Heroes #1 and Pteranoman came out from Kitchen Sink Press [both in 1990], and Border Worlds: Marooned #1 finally came out. [In the interim, Kitchen Sink also published The Return of Megaton Man, a three-issue series, 1988, and Megaton Man Meets the Uncategorizable X-Thems, a one-shot, 1989.] And one of these was this idea called Wendy Whitebread: Undercover Slut.

Again, I just make these things up as I go along. I had 14 pages of Wendy penciled and lettered, and I remember making photocopies and sending them to Thom Powers at Fantagraphics. I'd sent it around to other people before that. Last Gasp, the underground publisher, did not want it; it was too graphic. Kitchen Sink didn't want it, which was odd. Kitchen by this time was publishing Omaha the Cat Dancer, and they had published Bizarre Sex years before that, which was an underground anthology. So they had done some pretty graphic stuff. But Denis didn't even want to touch Wendy Whitebread.

What was interesting about that period was that it just brought in a whole different audience. I remember Gilbert Hernandez suddenly liked my stuff; other alternative creators suddenly liked my stuff. It wasn't like they were unfriendly to me before or anything. I remember Los Bros in the early days, and I loved Jaime’s stuff particularly. But suddenly when Wendy Whitebread came out, Beto-- suddenly we were colleagues, because he was doing Birdland, and it was like I hadn't quite been on his radar before that. There was a certain alternative crowd… I love Dan Clowes and Peter Bagge and those guys. I remember all those guys in the old days, and nobody was unkind to me or spat on me because I was drawing a superhero parody. But suddenly, Beto, we were hanging out at one of the San Diego shows. For five minutes or something like that.

You said in your last Comics Journal interview that Robert Crumb was a fan.

Crumb has said so, and I heard from intermediaries that he liked Anton Drek. In the Crumb documentary, there's a shot of Crumb and one of the Anton comics in the background at a comic book shop. Supposedly.4 But I've never met Robert. I met his late wife, Aline Kominsky, who came to a San Diego show one year. Pete Poplaski, who was the art director at Kitchen Sink and did the coloring on the Megaton Man covers in the early issues, many years now has been living in France, and I think he rents one of the outbuildings in the compound in the countryside estate that Crumb lives in. So Poplaski and Crumb have been close friends over the years, and I guess Crumb had visited Wisconsin in the ‘70s and stuff like that, but I've never met him. I understand he was a fan of Anton. But Anton gave me street cred with a certain class of alternative/underground people that I never had before, doing a superhero parody or even science fiction. Not that I was unacquainted with those folks before that, because I was always hanging out with Denis at San Diego, and I got to meet quite a few of the underground people that congregated in the old Hotel San Diego and so on. But suddenly I was like [Hustler magazine publisher] Larry Flynt or something. [Laughs]

After Anton Drek came the Image era in the ‘90s. Among other things, you brought Forbidden Frankenstein into your universe from the Anton Drek days.

Yeah, so I only did six comics [as Anton Drek]. Two Wendy Whitebread issues, two Forbidden Frankensteins, I did something called Dracula's Daughter, which was a sequel, a really hacked-out rush job, and then I did a thing called Anton's Drekbook, which was all just one-page cartoons or short little vignette stories. So I only did half a dozen Anton Drek comics for Eros, and they were collected in paperback [Anton's Collected Drek featuring Wendy Whitebread; 1992, expanded 1994]. They appeared from ‘90 to ‘92.

One thing I should say about the pseudonym is that while everyone knew Anton Drek was Don Simpson, it gave people a certain plausible deniability. Trina Robbins detested Anton Drek, but she had no problem hanging out with Don Simpson. That was a weird fact. The pseudonym somehow made it all a joke; it insulated the regular career of Don Simpson.

So anyway, ‘92 would then be the beginning of the Image thing. I was still freelancing stuff. One day Larry Marder calls me up. Larry was already the informal consigliere of Image Comics, this mafioso enterprise - he was like the Tom character from The Godfather who's the only character who’s not Italian, the Corleone family lawyer. Larry knew all the Image guys and he knew they were plotting this rebellion and putting this new company together. So he calls me one day and says, “Well, they're breaking out, they're gonna do this Image thing.”

Gary [Groth] had wanted me to do a parody of Image. He wanted me to do-- not to say a hit job, but he wanted to do a satire of Image, he wanted me to skewer them. The problem was that I had heard about it, and I didn't have a problem with Image. I had no problem with artists holding onto their toy royalties and movie licensing, and telling New York editors to go fly a kite. I told Larry about turning down Gary, and later Larry calls me back. He said he had told this to Valentino, who was studiomates with Rob Liefeld at the time out in California. So Larry says, “They want you to do a parody of Image Comics for them.” Like Not Brand Echh was a parody of Marvel by Marvel. “They want you because they heard you turned down Gary’s parody. They want you to do it for them. They want it to be an inside job on themselves.”

Luckily, Larry knew me well enough that you don't just give me a cold call, because I'll be like, “I don't know… it sounds like a lot of hard work, and I'd rather draw something else; let me think about it.” You know, very down in the mouth, not enthusiastic, because I’m weighing how much work it will be. But Larry shrewdly said, “They're gonna call you. Be enthusiastic. Don't blow this, it’s gonna be a lot of money - it's gonna be a big thing.” So I said, “Okay, okay, great.” So I got all psyched up and I get this call from Jim, and Rob's on the phone, and they say, “Hey, do you want to do your Image parody for us?” And I’m like, “Wow, that's the greatest idea I’ve ever heard!!” You know, very enthusiastic. So they start feeding me jokes about Jim Lee and Todd McFarlane, and I’m like, “Okay, great. I've got it.”

So I go to the Chicago Comicon that year, and I'm sitting in the Artists Alley in the hotel, and it's like a ghost town, because everybody's all lined up outside for these Image guys. Chris Ecker had the idea of pitching a big tent outside in the parking lot, and that’s where everybody was. Marvel boycotted that show, they were so upset that the Image guys were getting special treatment, which was really stupid because the only show in town then was to see the Image guys in the tent. And it was a phenomenon, right? So at one point somebody comes inside the hotel and finds me in Artists Alley and says, “Hey, they want to see you out at the Image tent.” And, of course, I have my photocopies of the first five pages of Splitting Image!, which was all I had gotten done at that point. And I go out there. Of course, I know Valentino, and I'm sure I'd faxed somebody something, but you know, Erik Larsen's reading the pages for the first time, and Todd's reading the pages, and they're all laughing and everything's going great, and then Erik says, “Hey, why don't we do a team-up? You know, I've got my Savage Dragon character, and he can meet your Megaton Man.” And again, I'm like, “Gee, I have to think about it.” [Laughs] And we're hanging out, you know, and I remember I was kind of sucked along into this parade of people, and we're hanging out, we're having pizza in the con suite and so forth, and I'm kind of an honorary Image guy because I'm doing this Splitting Image! thing.

So I wake up the next morning thinking, “Duh! What am I thinking?! I’ve got to do this Savage Dragon-Megaton Man team-up!” So I run out to the Image tent, and I tell Erik, “Oh yeah, oh yeah! This will be great, The Savage Dragon vs. Savage Megaton Man, it will be so kick-ass.” Dave Olbrich, who was the Malibu publisher [Image published through the already-established Malibu Comics until early 1993], he's just taking down notes like of all the projects these guys are suggesting, and not questioning the logic or the production schedule or anything. Just, “Tell me what you want to do.” Marc Silvestri’s throwing titles at him, Jim Lee's throwing titles at him, “We're gonna do this issue, we're gonna do that series,” whatever it happened to be. Rob Liefeld had like 15 titles he was gonna do, and Dave Olbrich is just writing all this stuff down. And Erik and I sketched out a Savage Dragon/Megaton Man cover on some spare Marvel Bristol board or something in the con suite, just to get the handshake deal consecrated, so to speak. So, that's how all that happened.

Now, the 1963 thing, I tell this story in the back of X-Amount, I don't know if you want to talk about that next--

No, go for it. Go right into it!

All right, so then the next show is San Diego, and the same thing happens, differently rearranged. I knew Bissette and Veitch at that point. Like I said, I had already met Steve Bissette, I’m not sure when I met Rick [Veitch]. I think I already knew Rick a little bit, but I knew something was in the works - they were cooking up something, I don't remember how much I knew. But I knew it involved Alan Moore, and it was gonna be a pastiche-parody-homage to the early Marvel comics. And I think I was being discussed as the letterer at that point, but it was not clear. So again, the same things happened. The Image panel’s going on upstairs somewhere in the San Diego Convention Center. We're way past the Civic Center, where the old San Diego con was; now we're down at the Convention Center. And, you know, the trade room is a ghost town, just like it had been in Chicago. I go up to the Image panel and there's like 5,000 people. This is the hugest thing I'd ever seen at a comic book show, and all the Image guys are on the dais and they're all talking about their titles that they're gonna be putting out. And at some point I was brought up there to talk about Splitting Image! and The Savage Dragon vs. Savage Megaton Man for like two minutes or something. [Both projects were published in 1993, Splitting Image! as a two-issue series.] But that was later. At first, I was still sitting in the audience, maybe in the first couple of rows, off to the side. And Jim Valentino was standing off at the side, and he's on the phone. And he comes over to me, he says, “Go find Veitch and Bissette.” I said, “Whoa, what?” Because, like any minute, they’re going to call me up to the dais. “Just get them up here.” So I'm running errands for Jim Valentino. [Laughs]

So I go down to the trade room, and I immediately find Veitch and Bissette, they're just standing around talking and chatting with people and stuff. And I say, “They want you up at the Image panel!” It's like-- what was that Leni Riefenstahl movie about the Third Reich? you know, the one with the giant beams of light--

Triumph of the Will? [Laughs]

Yeah - what city in Germany was that? That’s what the Image panel was like, it was like the Nuremberg rally. [Laughs] So we go up [into] this giant hall, and people are screaming, and Rob Liefeld is throwing hats out to the crowd, and mayhem is breaking out. I go back to my seat in the audience. But now Veitch and Bissette and Valentino are huddled off to the side under the exit sign, they're on the phone. Early cell phone days, you know, cell phones were still rather uncommon. And I was given to understand they were calling London or Northampton or something, they were calling England to get the verbal permission from Alan to announce this thing. And at some point there was a portable mic being passed around on the dais, and it comes over to Jim Valentino standing off to the side with Veitch and Bissette. And he announces to the crowd, “Alan Moore is coming back to superhero comics, and Image has got him!” And it's like, oh my God, the crowd goes wild. Like, the gathered multitude. It was the Second Coming. So Veitch and Bissette get the mic and talk about it, and Jim Lee is way over at the other end of the dais, as I recall. He's at the far end from where they are, over on the side. And he says, “I'm gonna draw the Annual! I’m going to pencil it.” And my impression was this was not premeditated, and it certainly wasn’t a foregone conclusion - it was not a done deal. Jim Lee just jumped in and said he was gonna do the art on the Annual. And of course, as we know, the Annual never happened. Everything else happened, the first six issues happened, but not the Annual. The Annual never happened.

But that's how deals were made in those days - if Dave Olbrich was around to write it down, or you would make a public announcement. Here's a sketch, we've got a handshake deal, this is what Image is doing. I mean, they were just going off the seat of their pants. If you let an idea hang out there for more than three days, they might have changed their mind, they might forget about it - they'd already be thinking of something else.

But my impression at the time—this may be retrospective—was that nobody really thought Jim Lee was ever going to pencil an 80-page Annual. And nobody was really surprised when it didn’t happen. But it was just glossed over and everybody proceeded as if it was all real. But it never came about.

So you do the Image thing, and then you get swept up in the self-publishing movement.

Right, so I had done one issue of Bizarre Heroes at Kitchen Sink in 1990, and then I was thinking of doing a kind of fusion universe. You mentioned Forbidden Frankenstein. I did this giant 15” x 24” print, and it was based on the Simon/Kirby letterhead, which had been reproduced in The Steranko History of Comics. Basically, it's a class portrait of all of Simon and Kirby's characters from the ‘40s that they were doing for different publishers. This was their letterhead, you know, for business correspondence. And Steranko blew it up and published it in his History of Comics, and of course, none of these characters actually ever teamed up because they were features created for different publishers. But it was always this captivating image to me, because they're all talking to one another, they're all chatting. “What’s it like working at Timely Comics?” “What’s it like working at MLJ?” The Red Skull talking to the Guardian and so forth. DC did a riff on it later - it looks like your third grade class standing on risers and everybody's all smiling and that kind of thing.

So I thought, I'm going to conventions, I was freelancing, but I had all these different series, and I had a certain audience for each series - Border Worlds and Megaton Man and the Anton characters. And I thought, maybe I could do something that I could sell at shows, maybe a portfolio; portfolios used to be a big thing in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Then I thought of this class portrait, this Simon/Kirby letterhead. And I would just put all my characters into one print, which would be less work and less expensive to print. So I draw on two huge sheets of Bristol board, and I put Megaton Man and Pteranoman, Wendy Whitebread and Border Worlds, Forbidden Frankenstein, and all these characters, all together in a class portrait. And then I could sell it to everybody, all my different constituencies of fans. Something for everybody, nobody is left out. I’m covering all my bases. [Laughter]

So I went ahead and did this thing, and I printed up 500 of them. I only sold maybe 75 of them, but that was more than enough to pay for it. But once I had created this thing, I had all these characters together, I realized, “Well, why wouldn't they meet?” With the Simon/Kirby characters, you could understand why Captain America couldn't meet the Guardian, because of ownership. But I owned all of my various characters. So I thought, “Well, I could have crossovers.” And then I started thinking of Bizarre Heroes #1, I wanted to follow that storyline, which was the start of a serious superhero universe. They create these superheroes in a laboratory - lots of people have done this thing, it's kind of a trope. They all break out, these superpowered characters - I call mine megapowered characters. And it was a dramatic, straight superhero idea. But I thought, well, why don't I bring in the Phantom Jungle Girl? I'll bring in Pteranoman, I'll bring in the Meddler-- which was a character from junior high school, he was already in the first issue, as a matter of fact. I'll bring in Cowboy Gorilla, and Yarn Man and all of the Megaton Man characters. So then I started thinking it could be an ongoing series. At the time, I didn't have any money to self-publish, and I had already broken off from Kitchen Sink Press. But then along comes Image, and there were some big paydays suddenly dropped in my lap. And after the dust clears from that, suddenly everybody has a pile of money and everybody's self-publishing, as you said it. Not just me, there was Jeff Smith, Colleen Doran, James Owen, and of course Larry Marder had been self-publishing for a while. But Bissette and Veitch both made a pile of money from 1963, and that was kind of the purpose of it.

I think Veitch and Bissette had initially planned for 1963 to last much longer, to generate spinoff solo titles for N-Man and the Fury and Mystery Inc. and so forth, and to bring in other collaborators after Alan moved on. It was always intended to be a cash cow, a commercial gambit - that’s why it was straight superheroes, after all. Only, I think they expected it to last much longer, maybe go for a year or two with them as the editors. It was supposed to be a bigger cash cow, in other words. They kind of had to switch to Plan B a lot sooner than they expected.

In any case, we were all self-publishing after our Image experiences. Dave Sim-- who never has been able to resist when a parade is going by his window, he has to run out and jump in front of it. So suddenly Dave Sim is rebranding himself as a self-publisher. But if you have any sense of history, you know Dave Sim wasn't a self-publisher, he had his girlfriend and then his wife Deni Loubert as a partner, and he gave her no credit whatsoever - and in the misogynistic world of comics at the time, we all accepted this, we assumed Dave really did do everything himself. So we’re all killing ourselves, trying to live this Dave Sim ideal which is just utter bullshit. Because Aardvark-Vanaheim had been a husband-and-wife publishing team, like Richard and Wendy Pini at WaRP Graphics, Elfquest. That was a thing, being a husband-and-wife publisher. And it’s no small thing, having somebody handling the business while the cartoonist is at the drawing board - the business partner is not just sitting there filing their nails.

When Deni broke off and took her A-V titles and formed Renegade Press [in 1984], only then was Dave suddenly a self-publisher. But by that point Dave was pretty well-established, it was a machine when Deni left. But none of us quite realized that. So suddenly now Dave's preaching about self-publishing, and he's saying you got to do it all yourself, and people are killing themselves trying to do it all themselves, and not factoring in the fact that there was another human being—Deni Loubert, in this case—doing a lot of the grunt work for Dave, so he could sit at the drawing board and be a genius. [Laughter]

In any case, everybody's doing self-publishing. I'm doing Bizarre Heroes, and it had been a goal of mine to incorporate the Anton characters in some way, to establish that they were in the same universe. With Frankenstein, that was very easy; all you have to do is put clothes on Frankenstein, and he's just Frankenstein. He's no longer Forbidden, he's just Frankenstein. One of the last issues of Bizarre Heroes, the 16th issue, was called "Megaton Man vs. Forbidden Frankenstein No. 1," and nobody was bothered by that. There's Frankenstein and he's got clothes on, and it’s a PG comic. Nobody’s pausing to think, “This is a XXX IP!” But by that point, I was kind of giving up on the Bizarre Heroes brand. I managed to do it for two and a half years [1994-96], but the self-publishing thing was proving as short-lived as the black & white boom. Books were dropping in sales, and then the industry—I should say the distribution system as we knew it—collapsed.

Friendly Frank’s, Capital City Distribution - there were like six or eight major distributors. I forget the sequence of events, but I think DC went with Diamond and Image went with--

Marvel bought Heroes World, then DC went with Diamond, then Image went with Diamond, and then it was all over.5

Yeah, I've kind of blacked all that out. It was very painful. Not as painful as when I put Border Worlds on hiatus, but still painful. I was doing my thing and just finding my groove. I had the serious superhero megaclone storyline, but Megaton Man and company had reasserted themselves into the proceedings. It was like Berkeley Breathed doing Bloom County, then doing Outland and Opus, but eventually they just turned back into Bloom County after a while.

In any case, when the distributor thing happened, suddenly all the cash flow seized up for all us smaller publishers, because dealers were paying Diamond but not paying Friendly Frank’s or Westfield or Capital City. So I was getting part of the money for the last few issues of Bizarre Heroes, but Capital City went into bankruptcy and it took several months to finally get paid. I finally got paid off, but it was pretty clear when Friendly Frank’s went out that my cash flow was not going to permit me to keep going. Sales were also going down. And I had burned through my Image Comics nest egg - I’d bought a Macintosh Quadra 800 computer, laser printer, scanner, a photocopier, the whole works. Nothing extravagant, like a sports car, but optimistic that I’d make it back with Fiasco Comics [Laughter] I wish I had bought a sports car instead and traveled up the California coast.

So you left comics.

Yeah, I realized at that point that I had a good long run. I had 12 years. I managed to get my imagination down on paper, for better or worse, and I wasn’t burned out, but I knew I would become burned out if I tried to persist. And I knew I wasn't going to be in line for more freelance work from Marvel or DC or Mirage - not this time. I realized that just wasn't going to happen, because I was always on the weird end of the spectrum with Wasteland and Turtles and weird odd jobs. I was never given a real shot at a mainstream, monthly superhero title, you know, even though I was born to draw Spider-Man. Larry Marder used to joke about how every artist in the industry was born to draw Spider-Man, or they thought they were. In the ‘80s I was already too old school for what they were looking for. They were looking for the next Rob Liefeld, with a kind of itchy style and all that itchy-scratchy inking, and I couldn't do that - beyond a brief, hit-and-run parody. I was old school, like Romita, Buscema - I was a How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way kind of guy, and I was already outdated, on top of being a well-known heretic and an asshole, and writing letters to the Buyer's Guide and The Comics Journal. I'm still doing the same thing today, by the way, online.

So I just knew I wasn't going to be in line for freelance work. Jeff Smith, Bone was going to Image, and it didn’t seem like there was going to be room for anybody else, any of us lesser self-publishers. I figured, “I'm not going to fight this. I'm kind of tired out. I need a break from this. There’s more to life.” And that was it. I was out of it. I remember the last San Diego show that I was at; the writing was on the wall. I guess this had to be ‘96, because that was when the Republican convention was coming into San Diego right after the Comic-Con. I remember sitting out on the balcony of the Marriott, Larry Marder’s hotel room, and we're looking out, and night had fallen, and we're smoking a joint. And all over the skyline of San Diego you could see these red, white and blue elephant kind of things - decorations were going up all over the town for the Republican convention, which was the coronation of Bob Dole and whoever his running mate was.

Jack Kemp?

Jack Kemp, yeah. I just remember sitting there on the balcony and thinking, “You know, I'm done. I've had my run. I've done X-number of comics, I had my Image fling.” I still had some money in a retirement account and I had some prospects. I just thought, “Whatever happens next in comics, this is not going to be for me. I'm not going to bash my head against the wall.” I just felt it was going to be a real tough road ahead for the guys who stayed in.

So you went to school?

I did. Back in the '80s, after the black & white bust, I had [gone] to art school for a year and a half, while I was doing nine pages of Wasteland every month, which wasn’t much of a workload. But that was a whole pocket universe. That was actually the late ‘80s, when I first came back to Pittsburgh, and I went to this rather ramshackle little art school and got an associate’s degree. I thought I would go into commercial illustration or something like that, but that industry was already on its way out because of technology and so forth. That associate’s degree, by the way, is so worthless I don’t even list it on my CV anymore. And the art school is gone too.

But in the late ‘90s, after the Image thing and the distributor collapse, that was a whole different episode. At first I was looking for freelance, and I did manage to get some freelance in the graphic arts field in Pittsburgh, and I even did a few commercial comic books using my straight superhero style. I always thought of the commercial jobs Neal Adams did, that were somehow more conventional and less innovative than the stuff he had done in comics.

So I was doing that for a while, but again it was kind of sporadic, and much like Steve Bissette ended up at a video store,6 I ended up at a Borders Books in the north hills of Pittsburgh. So around 2000, 2001, I got a job at Borders. I remember this because it was maybe a few months before 9/11. There was this thing, Harry Potter, which I was completely unfamiliar with. I remember the first day walking around Borders with the assistant manager - they gave me a name tag with a lanyard, and they showed me around the store, even though I was fairly familiar with it already as a customer. “Here's the local section, here's the philosophy section, here are the dictionaries, here are the Bibles, and here's romance, and here's literature, and here's young adult, and oh, there's this thing called Harry Potter,” a couple shelves in the kids' section, what they called “middle readers.” But they also had displays in the middle of the store, and at the check-out counter.

After I’d been working there a few days, I remember walking into the store one day, and the whole store seemed like it was covered in green. It was [Harry Potter and the] Goblet of Fire - it was all over the place. And I figured out in retrospect that they must have hired me because Harry Potter was so massive - it was a huge amount of their profit margin, and they needed additional labor because of it. Unbelievable. Books were flying out of the store like a special effect. I'd never read a sentence of it in those days, but I certainly handled 15,000, maybe 20,000 copies over the next five years. And I was only working there part-time. But I was at Borders for [Harry Potter] books four, five and six, and that was an unbelievable phenomenon to witness. It was the opposite end of the publishing business. And at the same time-- here's the kick in the head: I don't know if your voluminous research has uncovered this, but I did this book, Al Franken's Lies and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them [2003].

Oh, yeah. Not only did I dig that up in my research, but I bought that book when it came out!

Well, while I was part-time at Borders, I got this freelance job doing illustrations for Al Franken - he needed somebody to draw his chapter “Supply Side Jesus,” which was supposed to be kind of like a children’s book, a parody. And “Operation Chickenhawk,” which was all about the Republicans who got out of serving in Vietnam. I got a pretty good page rate, and I got to meet Al - I’d gotten the gig through an editorial cartoonist here in Pittsburgh, and I guess every other editorial cartoonist they knew at the time was busy. [Laughter] But the irony was, I'm literally working at Borders ringing up books, and I do this job, and I turn it in. And I’m expecting maybe 50,000, 60,000 sales, like Al’s last book, Rush Limbaugh Is a Big Fat Idiot. But instead, there’s a whole sequence of events - Fox News and the feud with Al Franken and Bill O'Reilly, and the lawsuit over the phrase “Fair and Balanced,” and suddenly this thing is doing like three, four million copies in print. Image comics like Savage Dragon/Megaton Man sold maybe 300,000, 500,000 or something like that. But literally the Al Franken thing went to like five, six million copies in print, hardcover, paperback - it was on the New York Times bestseller list at #1 forever. And I'm standing at the cash register with my name tag and lanyard, ringing them up. [Laughter] I’m scanning Harry Potter, Harry Potter, Harry Potter, and putting them all into a bag, and then scanning Al Franken, and putting it into the bag, and like The Complete Idiot's Guide to Auto Repair, and putting it into the bag. [Laughter] And I'm thinking, “Should I ask the customer if they would like an autograph?” [Laughter] Wouldn't that be weird? I should have tried it just once. “You know, I can autograph this for you.” And do a little Supply Side Jesus head sketch for them, and autograph [it] while I'm ringing up books for seven bucks an hour.

It was so strange, man. I mean, it was a good little gig, but you know - you get a gig like that and it takes you a couple weeks to draw it in the evenings, but you're still doing your day job. It was a very strange juxtaposition, being at two ends of the publishing industry at the same time.

But you did go back to school, and went so far as to get a doctorate.