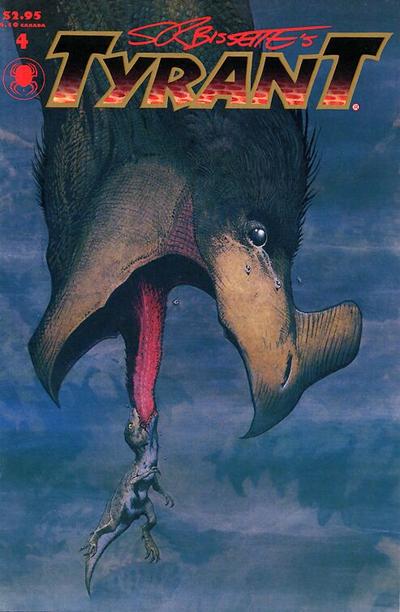

In his 1996 interview with Kim Thompson in The Comics Journal #185, Stephen R. Bissette boldly declared that he planned to spend the next 15 years writing, drawing and publishing Tyrant, his series detailing the complete life cycle of a Tyrannosaurus rex. Bissette had every reason to be confident in that plan. The book was riding high with strong catalog sales, and the fourth issue was on its way to store shelves. Sadly, it would be the last.

It’s safe to say the 27 years that followed didn’t go as expected for Bissette. His journey took him into video retail and academia, and while he never completely walked away from comics, perhaps at long last some part of his future involves drawing them again.

I caught up with Bissette over Zoom to talk about that unexpected journey, as well as the enduring legacy of his work on The Saga of the Swamp Thing, and what made his horror anthology Taboo so special.

-Jason Bergman

* * *

JASON BERGMAN: I thought I would start with a simple question: are you retired from comics?

STEPHEN R. BISSETTE: I stepped away from the American comic book industry such as it was in 1999. Foolish as I was, I announced it on the Comicon discussion board and instantly got the shit kicked out of me by Gary Groth and Kim Thompson, who tag-teamed all over me. That was the perfect sendoff, Jason. [Laughs]

So I did announce my retirement from the American comic book industry 24 years ago. I have occasionally dipped my toes back in, I did some work on three I think, SpongeBob SquarePants comic book stories, because the editor, Chris Duffy, was a good friend. I also have contributed to a few graphic novel projects over the years—introductions, forewords, afterwords, text essays—but I've turned down pretty much every overture.

About three-- well, we're going on four summers ago, I was approached by my friend John Jennings, who I met through my teaching years at the Center for Cartoon Studies, and John invited me to collaborate with John and fantasy novelist Nalo Hopkinson on a project that they had put together.

Together they decided they'd like to have me involved, so I finally stepped out of retirement to say yes to that project. Hopefully, we'll be starting work this year. The wheels of mainstream graphic novel publishing move very slowly, but Nalo delivered a first draft script and is currently revising that into a second. We're waiting for input from the editor and then I hope to be getting in gear.

I'll be doing thumbnails, layouts and pencils on the project. I work analog, I'm still old school, I scan the pencils. John Jennings does all of his work digitally. He and I jammed on a few individual pieces over about a three-year period off and on; you can see our first published collaboration on the cover art to my recent sketchbook, Brooding Creatures. We're both pretty happy with the results of the collaborative work we do. It doesn't look like what I do, and it doesn't look like what John does. I find in collaboration that's a good thing.

Is that your first published comic story in years?

No, I've been doing stuff all along. I taught for 15 years at the Center for Cartoon Studies, and off and on, over those years, students and alumni occasionally would ask if I would contribute something. I've done a fair number of short comics stories over the years for their anthologies (Sundays [vol. 1, 2007], Dog City [vol. 2, 2013], Dead Man’s Hand [2007], Tales from San Papel [2010], Dark Corners [2009], Awesome 'Possum [various from 2015], etc.) and other CCS community anthologies (Secrets & Lies [2008], It Is the Bad Time [2016], etc.). I also did a couple of original pieces for Accent UK, an independent publishing firm in the United Kingdom. I did a collaborative piece with my son Danny for Zombies [2007] entitled “An Alphabet of Zombies”, which Chuck Forsman and I later reprinted as a color poster print.

And I did a one-shot original piece that I wrote and drew for a western anthology that Accent UK published, Western [2009]. So I've kept my hand in it in terms of drawing to please myself when outside folks invited me, but nobody pays attention to that stuff, it’s all been pretty much ignored, and I’ve yet to collect that work in any form. [Laughs] The students knew of it, and people who are staying on top of some of the individual creators who were part of the Center for Cartoon Studies probably saw that work. I've even sent comp copies out to comics journalists, and so on, but I never hear anything. So fuck it. [Laughs] Per usual, I do it for myself, really, for my own pleasure

Let's go back a bit then, because your last interview with The Comics Journal was in 1996.

Yes.

That interview with Kim Thompson was extensive and you covered a lot of ground. I don't want to retread any of that, but there are a few areas I want to expand on. First off, you talk a lot in that interview about what your plan was going to be, you say specifically, for the next 15 years of your life.

Then the direct sales market imploded.

Right. I want to talk a little bit about that because you said you had this 15-year plan for Tyrant. At the time of that interview, you were just getting issue #4 out the door, which unfortunately was the last one. Can you go back and walk through what happened?

Actually there's one Tyrant piece that saw print after that. I did a piece called "Tyrant in Slumberland" for an anthology called Sundays that was put together by Sean Ford, Chuck Forsman, Alex Kim, Joseph Lambert, Jeff Lok and Bryan Stone, who were part of the 2008 graduating class at the Center for Cartoon Studies. It was my ode to Little Nemo in Slumberland, a riff on the classic poem “Casey at the Bat”. So there was a successive Tyrant piece that saw print, and that editor Chris Stevens later included in the crowdfunded first edition of Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream; it didn’t make the cut for the mass-market edition. C’est la vie.

So let's see - at the time of that interview with Kim, many of us were optimistic about the future, the direct sales market was still thriving. [But] there were clear warning signs. A very good friend at that time was Larry Marder, creator of Beanworld, and Larry was somebody who had his finger on, it seemed, every pulse in the industry. There were a number of us who called Larry, without joking at all, 'the nexus of all comic book realities' because Larry seemed to really understand what was going on in the big picture.

I remember at the time that Marvel went direct distribution with Heroes World, Larry called that Pearl Harbor. That was the beginning of the end for many in the 1990s wave of self and/or independent publishing. He was right, the dominoes fell very quickly thereafter. At the time, Jason, I was active as a self-publisher, along with a circle of very close friends and associates, including people like Rick Veitch, Colleen Doran, Jeff and Vijaya Smith, Paul Pope, Don Simpson.

We were doing the trade shows. And to explain what trade shows were, when the direct sales market had multiple distributors, the big distributors, Capital [City] and Diamond, had annual trade shows where it was very expensive to go. It wasn't just a normal convention cost of travel and the hotel room, but you would have to buy a table at their trade show, which if memory serves was about a thousand bucks.

But if you did that, you then had two days of meeting with all the key retailers from around North America, Canada and the US, and some who came over from the UK, and that was incredibly invaluable, especially [when] launching a project like Tyrant. Rick Veitch was launching Roarin' Rick's Rarebit Fiends. Don Simpson was ramping up his self-publishing imprint, Colleen Doran was still doing A Distant Soil. Jeff Smith was really picking up steam with Bone. Those trade shows were instrumental, and there were a number of peers, people I had met when I first entered the field, Jason, like Charles Vess, who were also self-publishing at that time. So it was this cross-generational embracing of self-publishing as a viable means of getting our work out there into the direct sales market. But Marvel went direct with Heroes World, meaning any retailer who wanted to carry Marvel comics could only buy them through a single distributor, this small New Jersey outfit called Heroes World. That set the dominoes falling and within-- oh god, I would say within less than a year of that Comics Journal interview seeing print [in March 1996], everything imploded.

I remember being at the last Capital City trade show and we were getting reports from upstairs down to the trade floor as to how the negotiations were going between Image Comics and reps of Capital City. Our livelihood hung on what was going to happen with those negotiations. Once word came down that Image had gone direct with Diamond, that everything had fallen apart with Capital, the writing was on the wall.

I remember being at the bar after hours the first night. Paul Pope and I were sitting at the bar. Paul is a lot younger than me, but we hit it off as soon as we met. I got to spend, I don't know, about a week in Columbus, Ohio, and I got to spend some time with Jeff and Vijaya Smith, and I got to spend some time with Paul.

Paul and I were so depressed at the bar that we were playing a game of sketching on napkins, drawing our favorite monsters from Jack Kirby's Kamandi series. Sliding the napkin over to the other guy, and you'd have to say what issue number the monster had appeared in. This is how despondent we were, Jason.

We knew the party was over at that Capital City trade show when Milton Griepp, who was one of the two proprietors of Capital City, got up to deliver a speech on day two - and by day two, everybody in that room, retailers and self-publishers and creators, and anybody who was at that trade show knew this was it, this is the last trade show for Capital. And Milton is trying to put a good spin on it, and at one point he said: "For the leather and earring crowd, we will still have access to certain Sandman special editions and trade editions." We looked around the room and most of the retailers had leather coats and earrings on. Milton didn't understand his own market.

One of my favorite retailers I had worked with over the years came up after Milton's speech and shook my hand and said, "It's been great working with you and with Rick and all you guys. I'm going home, closing my shop, and reopening it next month as a tobacco store." That was the shockwave, Jason, and then the Diamond show was just like the tombstone.

I mean, it was like going to a wake because by then we knew it was over. The bitter irony is that I think it was the Diamond show, not the Capital show [that was the end]. They paid Will Eisner to come in and give a talk. And Will's talk was, "Don't kill this. This is the best thing that ever happened in comics, the direct market. Don't kill this." And Diamond had already killed it. It was done. So, long answer to your question, I pretty much went home and began strategizing my exit from self-publishing.

I had two teenage kids, the oldest of the two, Maia Rose, my daughter, was going to graduate [high school] in 2001. Danny, our son, who's a bit younger than his sister, had a few more years to go, and much as I love Tyrant and great as a debt as I felt to the readers, Tyrant is not my kid. Tyrant is my brainchild, and my kids are more important, and I was facing the hard reality of how was I going to make ends meet and get my family through what was gonna go down in the following years.

Just to conclude the answer for you, understand how devastating the collapse of the direct sales market was. The distributor who came out on top, Diamond, and the publishers who went direct with Diamond as part of the process of the axe falling, Dark Horse, Image, DC, they thought this pie that everybody recognized as the direct sales market was going to stay the same size. And we could see before we left that Capital City show that the pie was already shrinking significantly.

We were being told by retailers, in person, face-to-face with us, “We're done.” Holding the same place in the sales chart over about a one-year period of time was Todd McFarlane and Spawn. When he held that position before the implosion of Capital City, he held his top position in the sales chart, selling over 700,000 copies of whatever the current issue of Spawn was. He was still in that same sales position a year later, but holding that position selling a little over 70,000 copies of Spawn.

The market contracted beyond what any of us had imagined possible. It was almost like the collapsing of a star - the market almost went nova. And I was doing one comic. Tyrant sales were doing very well, but those sales, my ability to pay household bills, and so on, and continue working on the comic depended on reorders. My first issue of Tyrant went through four printings, and after four printings, I was selling about 32,000 copies per issue. Which for an independent self-published comic was great at that time.

Those would be dream numbers now.1

If I had gotten to the point of my first trade paperback of Tyrant, maybe I could have survived. Maybe. I got a very generous offer from Jim Valentino at Image. Image was offering, like, a protective umbrella to a number of self-publishers whose work they respected and would have liked to have worked with. And I declined, because, again, my imperative was to get my family through this. It wasn't a matter of getting Tyrant through this. Tyrant, that was it. That was over.

There were a couple of other folks who reached out to me and made very generous offers at that time, including Joseph Michael Linsner, and I really appreciated it then. I still appreciate it now, but I didn't need a band-aid. There was no way that I could continue to carry two households. My first wife and I were in a separation, moving toward divorce. Not acrimonious, but [a] major life change going on. I was supporting two households, and I wasn't going to be able to do it self-publishing any longer.

So what did you do?

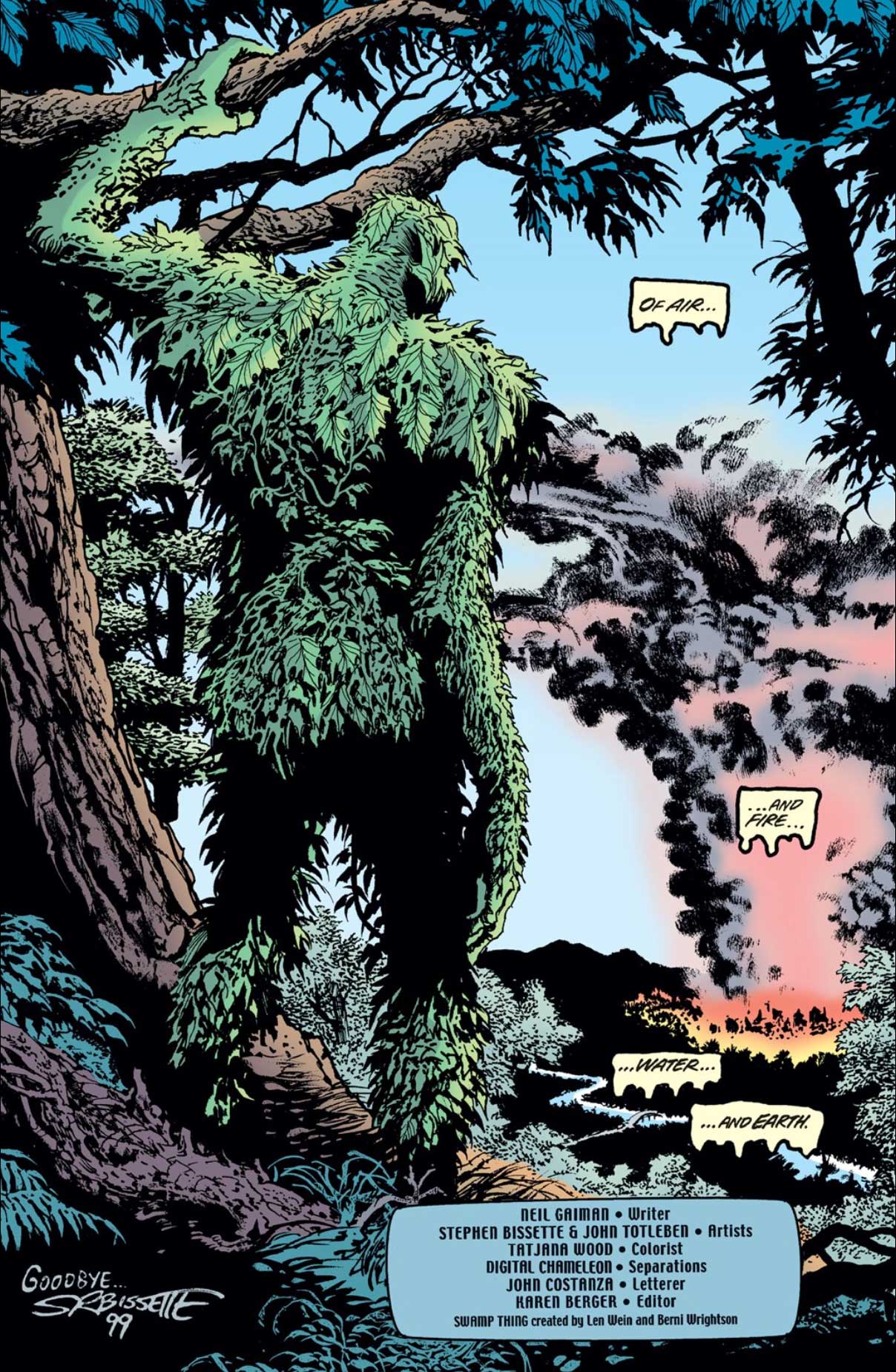

Good question. For a brief period of time I started accepting work-for-hire. I did a work-for-hire Tarzan script that my friend Tom Yeates-- Tom Yeates and I go back to first-year of Kubert School [i.e. the Kubert School's first graduating class], where we met in fall of '76. I wrote an original Tarzan script called “The Soft Parade” which Tom illustrated for Dark Horse [in Dark Horse Presents #143 (May 1999)]. This is when Dark Horse had the Edgar Rice Burroughs license for a time. I was approached by Neil Gaiman. I think I met Neil when he was 20 or 21. He approached me saying, "DC is going to do a collection of odds and ends material I had done" - I, meaning Neil, had done. "But I'd like you and John [Totleben] to illustrate my first-ever script that I submitted to Karen Berger." Because it was a 10-page Swamp Thing story, and Neil wanted it to be John and I. And his dream, he said, was that we would work at the level we had been working at when we were collaborating with Alan Moore on Saga of the Swamp Thing.

So I said yes to that. Whatever my misgivings about doing anything with DC, I said yes to that. Both jobs gave me an immediate crash course reminder in just how fucked freelancing can be. [Laughs]

Dark Horse took almost six months to pay me for that little Tarzan story. I negotiated an agreement with Karen Berger at DC, and part of the agreement was, as I turned in pencil pages-- it was only 10 pages, but as I turned in pencils, they would cut me a check. And that's because I now had child support payments to make every month.

Well, I turned in the first batch of pages, three pages. I was working on the next three, and when you asked what I did next, Jason, I was by this time in the video marketplace. I was working full-time 40-hour weeks at a video superstore, First Run Video, in Brattleboro, Vermont. I had been a shareholder in the business since about 1991, when First Run Video first opened its doors. I had worked for a few years as a promotional manager; one day a week, but enough to earn a modest weekly paycheck. It was a side job where I went in on Fridays and put together the newspaper ads and whatever promotions were going to happen in the video store that week or that month. And when I came back from the Capital City and the Diamond Trade shows, I called the proprietor of First Run Video, an old friend of mine named Alan Goldstein, who I'm still friends with. I said, "Alan, I need a job." He said, "You got one." He wanted me to be a manager and I said, "No, no, no, start me as a clerk. I need to understand every part of the business if I'm going to be working with First Run Video. I need to know what the clerks do, I need to work the floor."

So I was working 40-hour weeks at a video store. On my feet. Going home after hours, both my kids were in school, doing what parents do, and essentially being a single parent at that time. My first wife, Marlene, and I, we’re still friends, had shared custody of the kids. They would spend an equal time each week with me and with their mom, but during those times, we were essentially single parents during those periods.

I didn't get a check for my first three pages I turned in. I was about to FedEx the next three out and I called Karen because the end of the month was coming up and I said, "What's going on?" Karen said something along the lines of, "Our policy at Vertigo is we don't pay until the entire job is in." And I said, "Karen, we negotiated this contract." She said, "Well, that's how we do it at Vertigo." I said, "You just bought me a 60-hour week." I think I called her on a Wednesday.

Clerks at video stores are always happy to trade hours to get nights off or something. And I ended up doing a 60-hour week that week to make sure I could make my child support payment before the first of the month. I turned in what I had on pencils, there was one page left to go and I said, "I'm done. You broke the contract. I'm done." I apologized to John Totleben. There's one page in that story that John did from my rough thumbnails, all the other nine pages I had fully penciled. And that was it. 2

Those two experiences taught me I was not going to be able to make it working work-for-hire in the comic book industry. Why was I doing work-for-hire, Jason? You may well ask. My lawyer that I was working with, to see through the process of separation to divorce, said, "What are you going to do when a judge says you’ve got to get a job?” And I laughed. I was self-publishing Tyrant. I was paying the rent on both houses, January 1st of every year for the entire year’s rent, because Tyrant was doing so well. I laughed. And he said, "No, what are you going to do when a judge says you have to get a job?" And also he said, "Until the divorce is done, you cannot do any more work you own. You and your wife have to sort out and separate the proprietorship of these intellectual properties." Because under Vermont law, everything's 50-50, and that was part of what was on the table in this mediation process. He said, "You can't do any more creator-owned work until you're at the other end of this." So work-for-hire was suddenly my only option, and I had spent what? Twenty, twenty-five years working my way out of work-for-hire. When those were my first two experiences with work-for-hire, I just said, "Fuck it. I'm in the video business now." And I stayed working in the video rental and retail business from '98 until March of 2005.

And I have to tell you, I know it's of no interest to people in the comic book field, but almost everything I had learned self-publishing was applicable to what I was doing in the video retail market. This included experiencing all over again a variation of the same thing that just happened in the comic book field with consolidation of distribution: the home video imprints of the major motion picture and TV studios wanting to go exclusive. All that shit that I had just endured and survived in the comics field was happening within, I'd say, two to three years' time in the video retail business as well. As we all know there is no video retail business anymore, not as it used to exist. Crazy times!

That brings you to 2005. What happened next? Did you think about going back into publishing?

No, there were two things that happened. I'll keep them short. Number one, I got approached by an editor working for Byron Preiss, as part of his ibooks imprint, and they wanted me to do a trilogy of licensed Swamp Thing novels. Not graphic novels, novels. This would have been in 2004. We talked about it. I reached out to Karen Berger at DC. I had to make a pitch of what the story arc was going to be in the three novels because it would have to be approved by DC, and Karen was the point person in that approval process.

I cooked up a three-novel arc, featuring Swamp Thing, Abby, Arcane, the key characters that I'd worked with. The editor at ibooks that I was working with knew Swamp Thing. He was the one who had come to me and asked me what I write because he had read Aliens: Tribes, the novella that I had done for Dark Horse back in '94. I said, "Well, how about getting John Totleben to do the illustrations?" And the editor was like, "Yeah! That would be great."

I called up John. John was up for doing individual illustrations for these three novels. The problem was our publisher, Byron Preiss, didn't know who John Totleben was. The problem was our publisher didn't really know who I was. It was the editor who knew that we had worked on Swamp Thing and wanted us for this project. The synopsis I turned in to Karen was accepted, DC approved the three-story arc that I had cooked up.

We negotiated a contract and an advance and because it was three novels, the initial advance that was due to start work on it was going to be the full advance for the first novel. Preiss balked, saying, "I don't want to pay the full advance on the first novel until the book is in." I said, "Well, what am I going to live on when I'm writing the book?" And within about a month's time, the editor left the employment of ibooks, so I no longer had the editor who had first approached me.

I had a publisher who didn't want to pay the negotiated advance that everyone had signed off on. And the project fell apart very quickly. I called Karen Berger and said, "Sorry, Karen, here's what happened." She understood. No hard feelings, project over. Sadly, as it turned out, Byron was killed shortly afterwards in a car accident, July of 2005, so even if circumstances had worked out with the advances, the ibooks project would have been terminated before the first novel would have been delivered.

Oddly enough, I likely would have turned down a great life opportunity had I been working on the planned Swamp Thing novel trilogy. I guess the universe had other plans for me, right? I was approached right about that time by someone I had been corresponding with for a few years, James Sturm. James Sturm told me that he was going to open a cartooning school.

And I said, "Well, that's interesting. Where are you thinking about doing it?" He said, "In White River Junction, Vermont." I was like, "What?" Now, Jason - White River Junction, Vermont, I will not mince words, was at that time the asshole of Vermont. White River Junction, Vermont, was this key hub of business throughout the 19th century and into much of the early 20th century that had hit hard times during my lifetime.

All that White River Junction, Vermont, meant to me as a kid who had grown up in northern Vermont and later in my teenage years and in my 20s, had been bussing from Northern Vermont to Boston to New York to New Jersey; White River is where you got stuck when the bus stopped and you had to do a layover for two hours, and there was fucking nothing there.

There was one strip club that I wasn't old enough to go into. There was one Chinese food restaurant that was part of the bus station, and that was it. I couldn't believe what James was describing, but he said, "Well, why don't you come up to White River, I'll walk you around." I went up. I was living in southern Vermont at the time, I drove up to White River and James walked me around downtown White River. There were all these empty storefronts, all these businesses that had closed, and he said, "We're looking at this building, we're looking at this building." And I could see he was dead serious. This is something James was going to do. Somewhere in this process, Jason, James and I both got invited to a comics academic symposium at Bennington College in southwestern Vermont; Brad Verter organized and curated the event. We both were there, and I was there as a guest speaker. I gave a shortened version of this lecture I'd given for a number of years called Journeys Into Fear. It was a slideshow history of horror comics. I had done it everywhere, contracted and expanded (depending on the venue) from a half-hour version to a three-day version for one institution; my Bennington symposium version was 45 minutes or so with 10 minutes of Q&A, and it went over well. So James attended that, and after I was offstage, he said, "I need you. You're the guy I need teaching comics history." I went back up to White River. I met Michelle Ollie, who was James Sturm's partner in launching the Center for Cartoon Studies. While we were at that Bennington College event, James also showed me the original art that Seth had done for the first CCS brochure promoting the launch of the school.

I knew it was real. I had met Seth during my convention years, and I had met Seth when he was going through his Andy Warhol phase back in the Mister X days, when I would go up to Montreal or Toronto to visit friends. I knew and respected Seth and his work a great deal, and seeing that Seth had done this wonderful artwork for the Center for Cartoon Studies, I knew this was real. This was really going to happen.

I think that was February of 2005, Jason, and the whole deal with ibooks collapsed in April or May of 2005. Here I was leaving the video store. My springboard, what was going to get me through that year, was going to be writing these three Swamp Thing novels. That no longer was there, and yet James and Michelle are saying, "We need you. We need you at the school."

And so we had serious talks, and I was one of the first faculty members they hired. I was there when we opened our doors for the first summer workshop, that summer [of 2005]. Within two months of, "What the fuck am I going to do?" I sort of was back in the comic book field, Jason, without meaning to be back in the comic book field. But publishing had nothing to do with it. I was now teaching.

Were you teaching comics history?

Yes. It was called Survey of the Drawn Story. That was not my name for it, but such is academia.

That sounds like a course.

It's academia, my friend. Because of the nature of the institution that CCS was and is, I did not need a teaching degree or certificate. I did two years at Johnson State College, and then I did two years at the Joe Kubert School. I don't have an associate's degree. I don't have a bachelor's degree. I certainly don't have a degree in teaching. But for James' and Michelle's purposes, the fact that I had worked professionally 35+ years in the comic book and graphic novel field was all they needed.

So I was teaching Survey of the Drawn Story. I was teaching, and co-teaching, [another course,] Drawing Workshop. I was also the first instructor working with the senior thesis class, beginning the second year, once we had a senior class. It's a two-year program. I refer to it as freshman, senior, first-year, second-year. It was a full-time job. I have to say, James and Michelle were the best employers I have ever worked with or for. CCS took great care of me. It is a not-for-profit institution, so they were not withholding from my wages for income tax purposes or anything; the old lessons and methods of freelancing still applied. I had to strategize how I was going to make ends meet and how I was going to deal with being still self-employed, even though I was full-time teaching.

We made it work, and it was 15 years of the best work (and some of the finest creative) experiences I had ever had in my life. And it was 15 years of one of the most excellent life experiences I have ever had in my life.

I can only compare it to the adventure that both my marriages have been. I'm still married to my second wife, Marge. We're about to celebrate our 28th anniversary together, and our 21st wedding anniversary. I had 14 years or so with my first wife. And having kids. My life with Maia, Danny, and now through the marriage with Marge, sons Michael and Bill, that’s been life’s greatest adventure - and CCS was right up there. I can't fully communicate to you Jason, what those 15 years were like. But it was just amazing. We could (and someday should) indulge an interview session just about the CCS years and experience.

Did you start academic writing around that time too? Because I know you do a lot of essays and other writing these days.

I have been writing since I was a kid, and I was a very enthusiastic creative writer during junior high and high school, thanks in part to teachers like David Keefe and Carol Collins. My writing for publication began with my late friend, Chas Balun. Chas Balun launched a fanzine called Deep Red back in 1987. It was a horror film fanzine. Chas was one of the first people writing openly in the English language here in North America, with exuberance, about his unapologetic love for splatter movies.

Chas was right in there with the first wave, along with the first author of the first book on splatter movies, John McCarthy (Splatter Movies: Breaking the Last Taboo of the Screen [1981], published by Tom Skulan’s FantaCo Publishing out of Albany, NY, one of the unsung pioneer publishers for the genre). Chas invited me to contribute to Deep Red. I think I wrote him a fan letter. I bought the first issue of Deep Red and I wrote him a letter saying, "Hey, this is a great zine. I really enjoy it." He said, "Well, do you want to contribute?" I sent in some capsule reviews and I wrote an article about a film that had really blown my mind, a little independent horror film called Combat Shock, which was written and directed by Buddy Giovinazzo, out of Staten Island.

It was a really powerful little anti-war film, a really nasty piece of work too, made with almost no money. I interviewed Buddy, and that was I think the first long piece I did for Deep Red, and everything followed from there. I wrote for Fangoria. I wrote for Gorezone, for Craig Ledbetter’s European Trash Cinema (ETC), Charles Kilgore’s ECCO, Tim & Donna Lucas’s Video Watchdog, G. Michael Dobbs’s run editing Animato! and Animation Planet, and more. There was a whole network of zine culture, as you know, at that time. Part of the zine culture I had been tapped into since junior high were devoted to horror and monster movies, and I was all in for those, because I love horror films.

I was subscribing to Gary Svehla's Gore Creatures. I was subscribing to Richard Klemensen's Little Shoppe of Horrors, which was dedicated completely to Hammer horror films. I had my first fan art published in the pages of Greg Shoemaker's Japanese Fantasy Film Journal. This is all back in the late 1960s, early-to-mid '70s. So plugging back into the horror zine scene in the '80s felt natural to me. I know that this seems like an aberration to people that are just into my comics work, but understand I was plugged into horror zines long before my first comics work was ever published. It was Randy Stradley being familiar with my zine and newsstand magazine non-fiction articles and interviews that led to Dark Horse approaching me to write Aliens: Tribes.

It's funny you say that, because if you go back to those four issues of Tyrant, you've got 24 pages of comics and then 20+ pages of supplementary material, including movie reviews and other things.

Oh, yes.

I still have not forgiven you for your very negative review of Tammy and the T-Rex.

[Bissette laughs]

Did you see the director's cut? Because they--

I did. The director's cut is way better than the film that I saw on video. But I also have to say, I got to meet the actress who was the star of Tammy and the T-Rex, who's name--

[Laughs] Denise Richards?

Yes! I met her at the VSDA [Video Software Dealers Association] video trade show when Tammy and the T-Rex was brand-new. She was at a booth with the prop head of that t-rex animatronic model mounted on the wall behind her. I have signed photographs of Denise. I might be one of her first fans!

And you still published a scathing review of that movie in Tyrant!

It was a piece of shit! I love pieces of shit, but it was a piece of shit, Jason! I have to say, now that Vinegar Syndrome–I've contributed bonus features to one of the partner labels of Vinegar Syndrome, I've been doing work for Deaf Crocodile [a label focused on 'world' genre cinema, significantly from Eastern Europe]—has released the director’s edition, well, hell, I jumped on that Tammy and the T-Rex [re-release] immediately. A scathing review does not mean Stephen Bissette didn't love watching the movie, and that I would not hesitate to buy the complete director's cut.

In fact, Jason, I bought the second edition of Vinegar Syndrome put out because Chuck Forsman, who is an esteemed alumni of the Center for Cartoon Studies and a friend, did a special illustrated comics sleeve for their second release of Tammy. So I am the proud owner of not one, but two blu-ray editions of Tammy and the T-Rex.

Well, we could talk about Tammy and the T-Rex for the next hour.

We won't go there. But I'm glad you noticed that, and that level of writing is what I was doing for Deep Red, for Video Watchdog, ETC, ECCO, Animato!... there were a whole bevy of zines that I was contributing to. It's just like when I was doing work for comics: you see your work in print, you get better because suddenly you're seeing it with an essential remove. It's no longer “just” what you wrote. Now you're reading what everyone's reading and you're going, "Oh shit. I'm a really bad writer. I’ve gotta get better." [Laughs]

I worked hard on the pieces that I was doing for a lot of those zines. I wrote overviews of Abel Gance’s 1938 J'accuse (aka "That They May Live" in the US), which was a film almost impossible to see on video back then. I wrote an entire book on cannibal movies, We Are Going to Eat You!, which Alan Moore found hilarious and a great source of ridicule. But I was fascinated with-- where did these fucked up movies come from? What cultural zeitgeist leads to that cycle of Italian cannibal films from the late '70s and early '80s?

I love how the pop culture works. I love having been part of it and still being part of it. But I also love its ebb and flow, simply as someone who experiences the pop culture like everyone does, like you do, Jason, like all of us do. I try to understand, where does this stuff come from? Because it comes from somewhere. And all of that fascinates me. Any opportunity I ever have to talk to filmmakers, people who have acted in film, people who have directed films, people who have worked on any aspect of film, all of that is grist for my mill. It's the same with comics.

I've written a lot about comics, right up to this month that you and I are talking. I've got four new things in print since January 1st. Three of those are in comics. Like the Blacula graphic novel that was just published [Blacula: Return of the King, Rodney Barnes & Jason Shawn Alexander; Zombie Love Studios], I did the afterword to provide the context for the Blacula character. I also did a very lengthy introduction for the collected The Lonely War of Capt. Willy Schultz [Dark Horse/IT'S ALIVE!], which is a comic I grew up reading as a teenager and that I loved. It's a comic drawn by one of my heroes, the late, great Sam Glanzman.

So yes, that academic level of writing-- I'm glad you called it academic, because I think I do a pretty good job with it now.

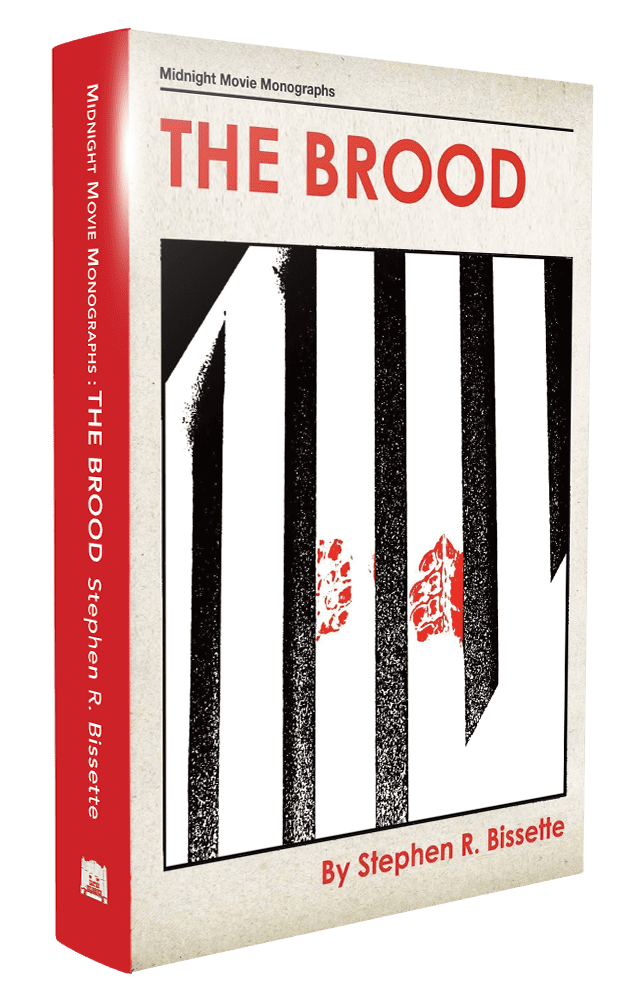

You wrote a thousand-page book about Cronenberg's-- was it Rabid?

No, no, The Brood.

The Brood. That's right.

It was only 700 pages. Well, that's the first edition. I'm about to turn in an additional bonus chapter. They want to do another edition later this year. “They” meaning Midnight Movie Monographs, from Electric Dreamhouse, an imprint of PS Publishing in the UK.

It was the same when I was doing Tyrant. I would finish an issue of Tyrant, and then there was new information from paleontological texts that changed what I had done before. It was the same with the Brood book. I worked for five years on that book: two-and-a-half years writing it, another two-and-a-half years that it took to finally see print, including the entire proofreading process. Once it's in print, new stuff is suddenly within my reach that I wished I'd had access to when I was--

That does bring up a good point. When you were doing Tyrant, the whole concept was that you were going to be as scientifically accurate as you could be. You depicted the life cycle, and put all this detail in. But the problem with that is that when you look at Tyrant now, the science has all changed!

Oh god. [Laughs] I have a very good paleontologist friend, Dr. Michael Ryan. We first met each other, I think in the late '80s. And Michael Ryan is also a good friend of Mark Schultz, Cadillacs and Dinosaurs/Xenozoic Tales. Mark is now collaborating with my old buddy, Tom Yeates, on Prince Valiant, the Sunday comic. So Michael has been my paleontological guru, and he was the man who opened the door for me to the world of paleontology when I began work on Tyrant, and I joined the SVP, the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. I was an active member for four years while I was doing Tyrant. I didn't let my membership lapse until getting back from that Diamond trade show and going, "Okay, I guess I'm in the video business now."

So four years ago, my late friend Mitch Berger bankrolled a research trip for me. I took two weeks and I drove up to Ottawa where Michael Ryan is based, and I was able to bring up to Michael photocopies of all the Tyrant issues. We went over every page, every panel, and Michael sent me home with two thumb drives of current papers. I've since been crash-coursing on the new paleontology.

I've been following it all along but as a lay person. I was no longer attending those annual events that the SVP held, where it would be three days of active seminars with cutting-edge paleontology and new discoveries and new theories and so on. So Michael brought me up to speed, and I also went up to Ottawa armed with scripts and thumbnail layouts for two new Tyrant stories.

Michael walked through those with me and I made some corrections. But he also chose which story I should do first. He was like, "This is the one." And it jived perfectly with my friend Paul Karasik offering a summer workshop at CCS on graphic novels where you can go in for a week to two weeks and work with Paul and the other students in that workshop to workshop whatever your current project is. And I brought in my two scripts and workshopped them with Paul Karasik and with the crit group I was part of during the week of that seminar.

I paid my money and I was there just like all the other students. And Paul chose the same story. He said, "This is the one you're going to do first." My hope, knock on wood, is that I'll be able to do that Tyrant story. However, I’ve got to pay mortgage and I’ve got to pay bills, and Tyrant doesn't feed those. Nobody ever paid me to do anything Tyrant-related, save for the research trip Mitch Berger bankrolled, bless him. It's that eternal vicious cycle of: what's going to keep roof overhead and food on the table while you work on your dream project?

Would you be returning to self-publishing for this, or--

You know, that's a good question. Since the year 2000 or 2001, I have been experimenting with print on demand. I started with a couple of books that I did with and for longtime friend Jean-Marc Lofficier, who has his own print on demand imprint called Black Coat Press. I did a book on Vermont filmmaking, Green Mountain Cinema, which is another one of my interests and passions; I later wrote essays on Vermont horror films for Arrow Video’s and Stephen Thrower’s blu-ray set American Horror Project: Volume Two, accompanying the 1976 shot-in-Vermont feature Dark August.

Part of my job at and for First Run Video, the video rental/retail shop I worked with and for-- between 1998 and about 2004, I used to write a weekly newspaper column reviewing new releases for a couple of New England newspapers. I later collected all those into a book series called S.R. Bissette’s Blur, five volumes in all - that’s an awful fucking name for a collection of film reviews. I also wrote Teen Angels & New Mutants, a massive book that's a biography of Rick Veitch and a deep dig autopsy of Brat Pack, Rick's graphic novel, and the whole of North American teen pop culture.

How does it work? Where does it come from? Rick attacked the dynamic of the comic book publishing industry and how the teen pop culture functions via Brat Pack as his expressive vehicle. In any case, all those book projects were print on demand ventures, published through Black Coat Press. I have continued experimenting with print on demand using CreateSpace until late 2017 or so, when it all shifted over to Amazon's Kindle POD platform.

I've done two sketchbooks to date, Thoughtful Creatures and Brooding Creatures. I did a book called Cryptid Cinema, which was the first of three planned books defining a new genre in monster movies that [had] always been there, but nobody had really defined as its own unique storytelling genre. Print on demand is now at the level where I can begin collecting my comic work that I own or co-own and put them out in collected editions. The ultimate goal, Jason, if I live long enough-- I turned 68 this year. I'm not a spring chicken, but if I live long enough, yes, I'd like to get the original Tyrant back into print in an archival edition. And I would be using print on demand in part to get the new Tyrant work out there.

David Lloyd, who I first met during my Swamp Thing years - V for Vendetta David Lloyd, not my good friend David Lloyd, who I worked with at the Center for Cartoon Studies. Two different people, both great guys. So, cartoonist David Lloyd has been editing and publishing his own anthology, the digital anthology Aces Weekly. I've offered one of the stories to David Lloyd, but he's been waiting now for what? Eight, nine years. [Laughs]

They're really good stories. I hope I get to them. Time will tell.

Well, it's funny, I'm going to call out something you said in your last Comics Journal interview: you specifically said that you do not like writing comics for other people. You said have a vision in your head, and you’re the only one who can get that down on paper. 3 Has that softened over the years?

No, it hasn't softened. One of the first comic strips I ever did was for my buddy Tom Yeates. We did a story that was a backup in Sgt. Rock called “Live by the Sword... Die by the Sword”. When Tom asked me to do a Tarzan story right after my lawyer had said, "You can only do work-for-hire" - I can write for Tom Yeates. I know Tom's work. I understand Tom. We're close friends. We've been on these oddly parallel paths. So I scripted the Tarzan tale I mentioned earlier, “The Soft Parade”.

When we were at Kubert School, Tom and I were the two students who were in love with the dead genres. Tom only wanted to do adventure comics. There were no adventure comics anymore. Bissette only wanted to do horror comics. There were no horror comics anymore. And we've both done it! Tom has drawn Zorro, Tarzan, Prince Valiant, the Lone Ranger. Tom has gotten to do all the great adventure heroes in comics, and I think I've done alright by horror comics in my career.

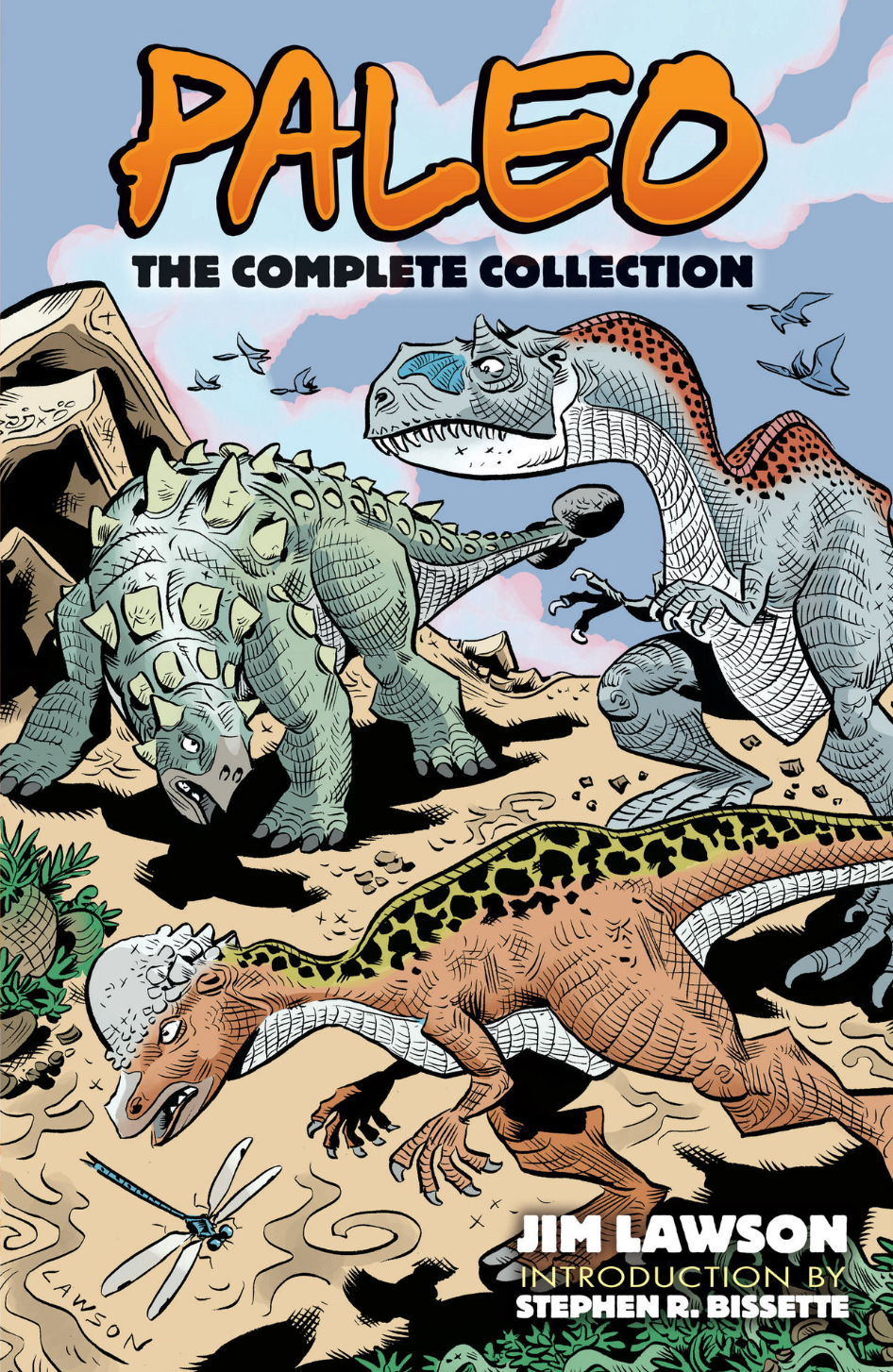

That said, I've also written-- all right, you brought up Tyrant. I wrote two scripts for Jim Lawson, for his dinosaur comic series Paleo. It was a lot of fun writing those scripts for Jim. It meant I could write about dinosaurs who did not live in the Upper Cretaceous period.

One of the limitations of doing a project like Tyrant, where I'm trying to adhere to the fossil record, is there's a lot of great prehistoric animals I can't draw because they didn't live when Tyrannosaurus rex lived. Scripting a couple of Paleo stories for Jim Lawson was fun because, "Hey, I can write about this dinosaur instead of this one."

So, with a few exceptions, I haven't softened on that view. When I'm working on a story in comics form that I'm passionate about, I just want to draw it. However, when I was teaching at the Center for Cartoon Studies, it was like living in a beehive. Everybody there was working their asses off on their own dream project. It's this amazing experience of being in the beehive.

Here, I can give you a concrete example, Jason: one of our alumni, Denis St. John, became a really great friend, and we had an opportunity to work on a character Denis loves, Vampirella. My pal Nancy Collins asked if I’d be up for contributing something to a Vampirella project Nancy was editing and co-writing, Vampirella: Feary Tales [Dynamite Entertainment, 2015]. Nancy was ok with my co-scripting a story with Denis, and our pitch fit the agenda Nancy had presented, but it was to be drawn by a designated art team, Ronilson Freire and colorist Jorge Sutil, who do really solid work. Unfortunately, either it was our failing, or simply a mismatch of aesthetics, but Denis and I were very directly spinning off of the famous Fleischer Studios Betty Boop cartoon Snow-White [1933], with the surreal animation style and Cab Calloway “St. James Infirmary Blues” bit. We made that explicit in our script, and the published final version retains our dedication to the memory of Roland Crandall, one of the animators credited on that classic animated cartoon.

Either our editor(s) or the artist(s) or-- well, nobody else got it, they didn’t get, and certainly couldn’t capture, what Denis and I were picturing. The look, the feel, the design, there was nothing, but nothing of the Fleischer animation universe reflected in the published version. Of course, Denis St. John could have caught it with his own artwork—see his solo six-pager “Satan’s Log Fume” in 666 Comics [2023], which is precisely in the style we were hoping for to illustrate our collaborative Vampirella script—but that wasn’t an option presented or an option we pursued. We were invited to script a story, and Nancy was happy with our script. End of the day, hey, I was able to work with Denis, Denis got to work with one of his favorite established comics characters, we got paid, and we had some fun. But once you let go of that script, well, good luck!

Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. As a writer, you have no control over the artwork in the traditional industry practices still holding sway in parts of the marketplace. You go in knowing that-- you give it your best, almost always everyone gives it their best (Ronilson and Jorge certainly did), but if the magic isn’t happening, if the visions aren’t meshing, if the chemistry isn’t there, for whatever reason, you get something that’s different than intended, different from what it might have been.

In an educational setting, you take all these as lessons, and hope they’re lessons learned. I wrote for others over the years, and no doubt I will again. I’ve worked for various editors for decades, and I will again, no doubt. I’ve edited a number of projects, professionally for publication (Taboo; two issues of Gore Shriek for Tom Skulan, which turned out well; attempted co-editing an anthology that didn’t work out elsewhere, etc.), and as an educator. I, at times, edited the students' work—for instance, every spring semester was kicked off with a two-week ‘create a color comic from scratch’ collaborative comic book project, and every year of that assignment I edited an assigned team’s project—but I had my own work, and it wasn't just the teaching work I was doing. I have to say the most satisfying experiences are usually when I’m doing my own thing, my own work. A lot of my own work was published between 2005 and when I retired from teaching in 2020. I did a lot of published work, including some of the work you've brought up, like the Brood book.

But everybody was working on their own projects, too, and the nature of collaboration is that if it's a fruitful collaboration, if you're working with people who understand each other, you can arrive at an alchemy that is unlike whatever you could do yourself.

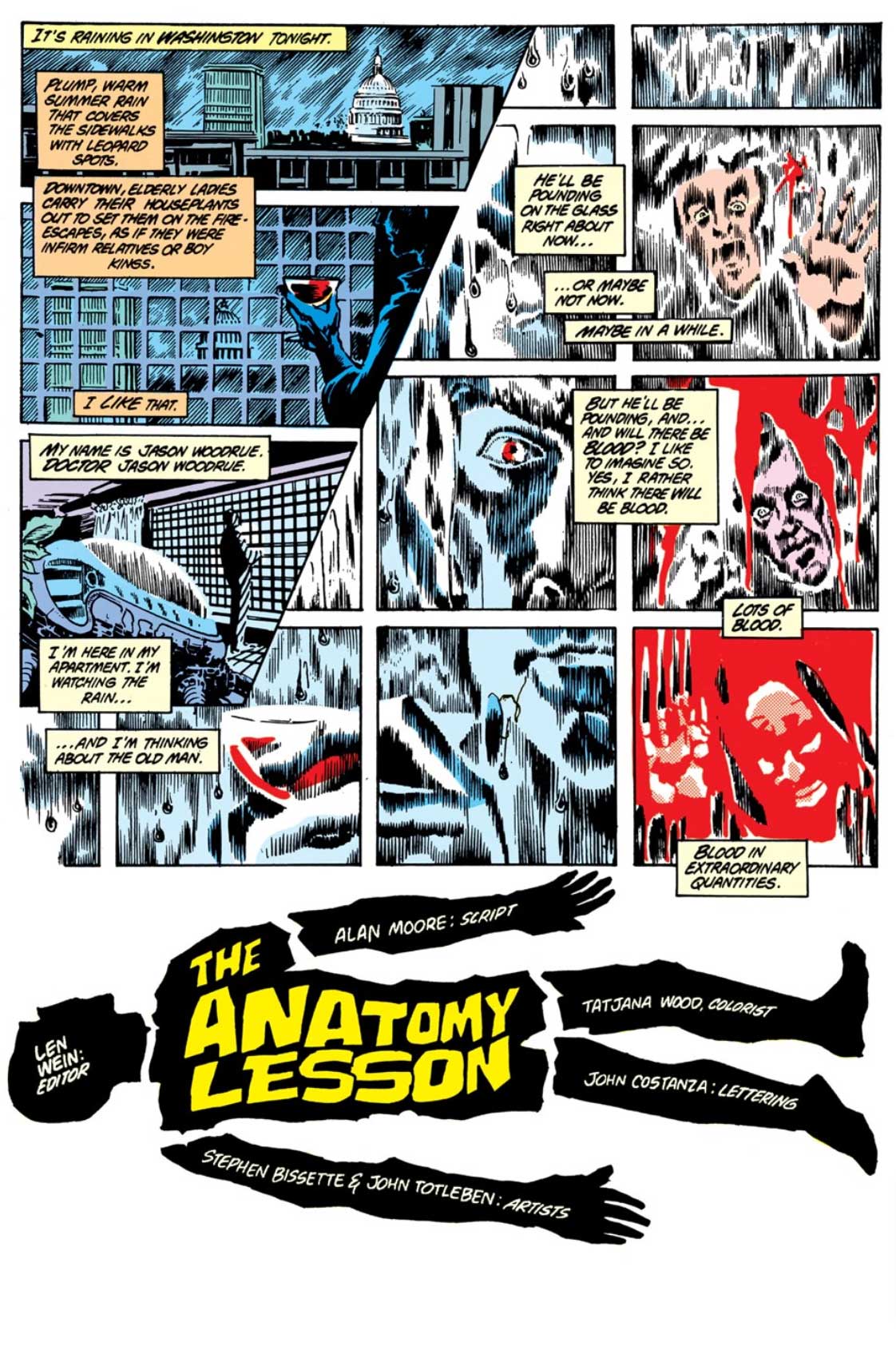

I alone couldn't have done what we did on Swamp Thing. None of us who were part of that unique team could have done it alone (although Rick Veitch came damned close to doing so, didn’t he, when he was writing and penciling his run on the title?). We, meaning Alan Moore, John Totleben, Rick Veitch, and everybody else that was part of that - Len Wein our first editor, Karen Berger our second editor; John Costanza lettered the book, Tatjana Wood was our colorist. That kind of chemistry yields work that, when it's really humming, is better than the work any of us could do individually. Having experienced that myself, I really believe that.

I went into Swamp Thing having experienced that kind of synergy with one of my oldest friends in the comic book field, Rick Veitch. Rick and I really did some work together that we're both still proud of.

Now, when I made that statement to Kim Thompson, I meant it, it was true: I’d had enough of collaboration for a time. I was insisting upon doing Tyrant on my own, apart from the research, for which I welcomed all the help I could get. Tyrant was a great experiment and experience. When I write, I usually write solo, to this day. But once I was in the CCS community, I was ready and eventually willing, even eager, to enjoy the fruits of collaboration upon occasion.

I've collaborated on a few projects over the years since the 1990s. When John Jennings reached out three or four summers ago and said, "Hey, Steve, do you want to play in this imaginative playpen that Nalo Hopkinson and I put together?" Hell, that sounded like fun, and I hoped I could bring something original to their concept and narrative. When it became apparent after two or three three-way phone conversations that I had something unique to offer to that, I was upping their game by bringing in something. It was very satisfying when they let me know, "Hey, we see you as an equal partner now."

I'm looking forward to doing that project with Nalo and John, but it's unlike anything I would have done myself. I never would have come up with the story they had come up with. I never would have pursued what I'll be doing graphically with that story. I never would have pursued what we will be doing narratively with that work, but I'm looking forward to doing it. Is it a distraction from Tyrant? Well, you can see it that way. In another way, having something come out from a publisher like Abrams will probably help Tyrant reach a wider readership, whether I self-publish it or I work with a publisher, than I would have had if I weren't doing this project with Nalo and John.

My father owned his own businesses, and I am a very pragmatic huckster, Jason. It's part of why I did okay as a self-publisher during those years. I have no problem with being a flea marketer, which is what you have to be at a comic book convention, as you know from SPX. Comic conventions are just big flea markets here in America. They're very different from the European shows. They're very different even from the Canadian shows. SPX is very different from your run-of-the-mill North American comic book convention, but they're still flea markets.

So as a huckster, I have to be pragmatic. I'm never going to be the genius wedding of creator and businessman that someone like Will Eisner was, or my mentor Joe Kubert. I always have in mind: how am I going to sell this? How's the business going to work? Part of that is, okay, if I'm going to do this project in order to get back to work on Tyrant, then that's what I'm going to do.

There are a couple of things I still want to touch on, but let's start with Swamp Thing. When you look back on Swamp Thing, what is it that makes that run - the Moore, Totleben, Veitch, Bissette run special? It doesn't just hold up, it is the defining run for the book and the character. And it wasn't the original, but it’s outshined that by far. Do you even know what it was about that exact moment that caused everything to come together so perfectly?

I don't know. I've been on this creative path long enough to know that windows open and windows close, and doors open and doors close, and they're usually finite in duration. Sometimes when those windows open, if you're there at the right time with the right people, you can do something extraordinary. Most of us only get one shot at that if we're lucky. I reckon back in 1983, it was the right group at the right time with the right people, on the right title, with DC in the right position of mercantile desperation.

They had been beaten in the sales by Marvel for so long that they were willing to experiment in ways they never had before as a publisher. We don't have time to go into all the layers of that, but if Paul Levitz hadn't been where he was, if Jenette Kahn and Dick Giordano hadn't been where they were, if Len Wein hadn't been in the mindset he was in, at that time, none of it would've come together.

Case in point, if anyone wants to get into the minutiae of this, I wrote a lengthy text piece in the back of the first volume of the Absolute Swamp Thing. I really got into, as best I could in that finite space, what it was that was unique about that period of time and that group of people, myself included, coming together.

And I interviewed John [Totleben] and Rick [Veitch] and John Totleben's wife Michelle Totleben as well, so that it wasn't just my perspective on what happened, but I was incorporating their memories of what had happened at that time. And, you know, if Alan Moore was still talking to me, I would have happily been talking to Alan as well to get his input.

But you can't make this shit happen, Jason. We were coming on the heels of some remarkable work that had recently been published, right? We drew inspiration from that work, from the generational context we were living in. That had fired us up. Dave Sim's Cerebus, Wendy & Richard Pini's Elfquest, Frank Miller's run on Daredevil, which had run its course at about that time. It wasn't over yet - Frank still had Elektra and a few other things in the hopper. Howard Chaykin's work, American Flagg! There was all this stuff happening at that time that was really firing on all cylinders, and Swamp Thing was the right vehicle at the right time for us.

Now, it didn't start with that team, right? John Totleben and I started on it [with issue #16] when Marty Pasko was still scripting The Saga of the Swamp Thing. What Marty was doing, it wasn't a horror comic. I don't know what it was, but we were working on it and we were happy to be working with Marty. We lucked into that gig because our Kubert School compadre Tom Yeates was leaving the book and convinced John and I to try out for the spot.

So when we came on, it was still Marty Pasko writing the book. Even though the chemistry was there for John and I, the chemistry wasn't meshing yet with Marty, bless his soul. He passed away a couple of years ago, three years ago now. Marty had his foot halfway out the door when we climbed on board—if I am remembering correctly, Saturday morning animation programming was providing a far more lucrative scripting career opportunity for writers like Marty—which became evident only two issues into John’s and my tenure with Marty on the title.

Len Wein called us and said, "You're going to be working with a new writer and it's somebody you've never heard of." And I said, "Who is it?" He said, "Alan Moore." I said, "Alan Moore! We love his work." Len thought I was bullshiting him. I said, "No, no, no. We've been reading Warrior since the first issue." We had been buying the UK black & white comic magazine Warrior from Heroes World, ironically enough - Ivan Snyder’s Heroes World New Jersey comic shop, the same mini-distributor Marvel later went exclusive with. The Heroes World comic shop in New Jersey carried Warrior, and we'd been reading "V for Vendetta" and "Marvelman" right from the first issue. We knew what Alan had been doing and we were psyched.

And this is what you can't explain, Jason. This is pre-internet. This is before we could have afforded a phone call to each other. We all wrote letters to each other, John Totleben, me, Alan Moore. All three of us. Our letters crossed in the mail. Alan wanted to do with the character exactly what John and I wanted to do with the character. What we wanted to do with the character, John had been pitching to Len via Tom Yeates, and Len had said, "No, no, no, no. Too radical." The whole idea of Swamp Thing not being a man inside, that he was this plant. That's what John said that the character should be, should run with.

Len had turned it down as an idea. For some reason, now that Alan was onboard, Len was open to it. Does that mean Len had let go of the character he had co-created to the point where he could do that, or because Alan so excited him as a writer that Len would trust him? I don't know, but we all wanted to do the same thing.

Furthermore-- Rick Veitch could talk to you about this. From the time Rick and I met, one of the things Rick said always captivated him is, I remember every movie I've seen. And this is pre-video era, so you would see a movie once or twice and you would try to remember it frame-by-frame, if you were crazy like me, because you might never see that film again in your life. And I was trying to make that kind of kinetic imagery and storytelling happen in my comics work, the aspects of cinema that I knew would and could work in comics, but I didn't have the writing skill to do it.

The filmmaker by name, and I've named him before in interviews, was Nicolas Roeg, co-director of Performance, director of Walkabout, Don't Look Now, The Man Who Fell to Earth. It turned out that Alan Moore loved Nicolas Roeg's work. In our first couple of letters, we found we were on the same page, that Roeg was a common reference point: something we could work from to forge a different way of doing comics.

If you go back and read "The Anatomy Lesson"—that first story that the team of us worked on together (all of us, because as I’ve repeatedly stated, Rick helped me on the pencils), so it was the four of us—it's structured like a Nicolas Roeg film, right? Nicolas Roeg approached storytelling like a mosaic, and you can move the tiles around. I always like to describe it as when Roeg’s approach to cinema is really working, you can tell the story from both ends to the middle—to the heart of the story—and you make the fireworks detonate in the reader's head. That's what Alan could do. He could already do it. Alan was scripting everything Rick Veitch and I had been talking about doing for years. We wish we could do this. Here's this script from this guy in England none of us have met, “The Anatomy Lesson”, and he aced it. And he fucking did it in what, 22 pages.

So right from that point, we all knew we're onto something, like, this is working. Alan would get fired up seeing my pencils. And what was happening, Jason, because there was no internet, is, we were moving all this stuff through the mail. I would photocopy in triplicate every pencil page I sent out to DC, and I would send a package to John Totleben and a package to Alan Moore and keep a set for myself. And Alan was seeing the pencils within a week to 10 days of when Len Wein and then Karen Berger had them. That was back when the US-to-UK/UK-to-US mail was functional and dependable.

Alan would get excited by what I was doing with the pencils, and then we would all see what John had done with the inks, and it would set fireworks off, and we were all pushing each other to go further. For a time, it was just a perfect synthesis.

I don't know how to describe it to adequately answer your question, because it's not the lightning in a bottle you can repeat or make happen, and we couldn't even sustain it. I vividly remember the night when-- John and I, we first met the second year I was at Kubert School because that was when John first came (he was part of the second class to ever attend the Kubert School). We were friends from that moment on, when we first met. We talked on the phone often, and I still remember the night where John and I both felt it at the same time, that our time on Swamp Thing was waning. John's way of phrasing it was, "You know, we put this car on the road and now they want us in the back seat."

And it wasn't long before we were exiting the book. We could feel the point where it wasn't that the magic had stopped happening for us creatively. It's that it was no longer possible to do what we had been able to do for about a year and a half working with DC. A lot of other forces were coming into play. Suddenly everything was caught up in the Crisis on Infinite Earths crossover, which I fucking hated with every fiber of my being, and the wheels fell off the car right at that point.

Well, you mentioned your relationship with Alan Moore is kaput. Is that due in part to this project? [Holds up an issue of 1963]

Well, shit, here we go. Ok. No, it was due largely to something I said in conversation with him in that interview in the Comics Journal.

It wasn’t where you talked about the 1963 Annual? 4

Was it me talking about the business? Was it me talking about what happened to From Hell: The Complete Scripts? 5 I don't know. There is a biography out about Alan where Alan goes on for almost a page about what he supposedly said to me, and, no, that didn’t happen - that's called “a conversation.” We didn't have a conversation. Alan said three sentences to me and hung up. 6 And it was definitely the draft version [of the Journal interview] he’d been upset by, because Kim Thompson and I spent about three hours on the phone after my call with Alan, trying to second-guess what might have upset him and re-edit it before it saw print, but we finally gave up; Kim and I decided, “Well, let’s let it see print as is,” for the most part. It was something in that interview, and Alan did not specify to me what it was. I’ve guessed at what it might have been, but I could be wrong. I think it was—and this is what Dave Sim said to me right after—that I dared to talk about the business relationship among creative people. I dared to say things like writers need artists. [Laughs]

I do want to talk about your legacy in comics. Because to me, there are three major parts of your comics legacy. There's Tyrant, there's Swamp Thing, and then there's my personal favorite from my younger years, Taboo.

I'm very proud of Taboo.

And I should say, I have a complete run right here. [Holds up a stack]

Oh, you got them all! Good. Good for you.

So, I went back and I reread the entirety of Taboo in preparation for this interview.

How did it read, Jason?

Well, it's interesting, especially after rereading your Comics Journal interview. The first issue is rough around the edges.

Oh yes.

And then you really hit your stride a couple of volumes in, and it’s just the best. But the last two are very… safe.

They were safe because they were published by Denis Kitchen.

Well, but what made Taboo special, and there was a time where I think Taboo was something truly special, was that there was a danger to it.

I agree.

Maybe it's because I was a teenager when these were coming out.

It wasn't just you, we got busted in every English-language country on the planet. Taboo was busted by customs in every English-speaking country. The only one that we ever got a favorable customs report from—I still have the photocopy proudly displayed in my library—was from New Zealand. They actually read the issue of Taboo that was under scrutiny and they passed it. They said, "This is a very mature, intelligent work." [Laughs]

In England they just banned it. They just said, "That's it." They would destroy any copies they came across. It was dangerous. It was as dangerous as we could make it.

It came across. I think at the same time, one of the things that made Taboo so special is one of the things that damned it, right?

Oh, yes.

You gave complete creative freedom and ownership to every one of your creators, which means, this stack of Taboos that I have here is pretty much the only version there will ever be.

That's it. I've had many people over the years come to me, wanting to either revive Taboo or do a collection, and it's not possible any longer. The creators who contributed their efforts to Taboo wholly own their own work. When Taboo ended, people didn't just get their original art back, we actually cut the negative film up and returned them to any artists that wanted those negatives.

So my pipe dream of a Best of Taboo collection?

If you can make it happen, Jason, I will happily write the introduction and work with you, but there is no publisher on earth that I have ever dealt with who was willing. They all wanted Taboo to be safe. Taboo was never safe. It was never meant to be safe. It was meant to be dangerous, even toxic.

And those two issues… I'm not complaining. Denis Kitchen made clear to me when we negotiated doing those last two volumes that there was a lot in Taboo he would not publish. I said, "I understand that." I'd grown up reading Kitchen Sink Press. I knew Denis' taste. I knew that Death Rattle, the Kitchen Sink horror anthology, in both its incarnations (the 1970s, and the late 1980s-1990s) was not Skull. I knew Denis' comfort zone, so I didn't go in with any reservations. Denis was the publisher. Phil Amara was the editor. Because I said, "Look, these aren't the books I would have put together, but whoever I'll be working with, I want them to get the editorial credit because they need it more than I do, and it's more representative of the last two books being Kitchen Sink publications. They are not really SpiderBaby [Bissette's publishing concern] publications."

I've been approached a number of times by creators, including Neil Gaiman who asked, "Steve, would you revive Taboo?" Christopher Golden, the horror novelist, approached me once too. And I laid out, "Here's how I would have to work." I won't go into everybody who has approached me over the decades, Chuck Forsman once approached me about doing an indie Taboo, but the problem is it's dangerous. The other problem is this, Jason: once we did Taboo, nobody had to do Taboo again.

All that time that I was at the Kubert School, and then entering the comic book field, and laboring as a freelancer, and lucking into Swamp Thing, and having it blossom into what it blossomed into, and pushing it as far as we could push it, including losing the Comics Code Authority [beginning with The Saga of the Swamp Thing #29] - well, that was part of my fantasy, my path. “Can I play some part in making horror comics viable and dangerous again?” I gave it my all. If there's anything I'm proud of, it's that we fucking busted the Comics Code. They didn't bust us.

And then Taboo was to try to push a genre that I love—horror—into the late 20th and 21st centuries. And once Taboo existed, I knew we had succeeded when I got a phone call from Karen Berger saying, "Steve, we're thinking about starting something like Taboo at DC, but it's going to be a whole line of books." It's what Vertigo became. Karen was calling to see if I would share some contacts with her, some of the creators who had done work on Taboo (which I did).

The minute I got that call, I went, "Well, I guess, mission accomplished.” If Warner, DC is looking at Taboo and going, "Huh, we can do something with some of this," then we succeeded in punching a hole in convincing the comics world first, and then hopefully the world, that horror comics did not just have to be regurgitations of EC comics. I love EC comics, but what was cutting-edge in 1954 was no longer cutting-edge in 1984.

I've got to tell you, re-reading Taboo, I don't know that there's anything else out there right now like that.

Sure, but even that genre term, horror, I hope you came away from revisiting Taboo going, "Wow, this isn't like, just horror."

Yes.

My book on The Brood, if you haven't read it yet and you can afford it-- [Laughs] I hope you'll read it because it's my treatise following Taboo on what horror is to me. Horror is to me a genre that is not just about being scary or being gross or being fucked up, it is about awe, it is about wonder, it is profound and essential, it is about tapping into the aspects of being a human being that we don't like to talk about.

The name Taboo—which was suggested, by the way, by Mark Askwith, who at that time was a friend that we'd met through Silver Snail, a comic shop up in Toronto—says it all, in that one word. "Taboo" sums up the importance of the horror genre. If it's something we're not supposed to talk about, then it's important. If it's something we're not supposed to show, then it's important. If it's something you're not supposed to write about or draw about, then it's important. If it wasn't important, it wouldn't be taboo.

Horror as a commercialized genre tends to not go as far as it should go, but thank god we do have creators that work in horror that are able to push it. Takashi Miike, David Cronenberg, Ramsey Campbell, we could list our favorites.

When you look at the current state of horror, because horror is having a moment now--

Oh, it's having a big moment, yes.

But a lot of it is very safe.

No. I've never seen it! Probably because I rarely get into comic shops anymore.

I don't buy them from comic shops. Jay does them as Kickstarters and you can order them through Black Eye. Everything's online now. Dwellings is Jay Stephens doing - well, it’s perhaps the best current horror comic I'm reading, but it's done as a Harvey comic, like Casper, like Wendy the Good Little Witch, only it's really fucked up, and it's called Dwellings. This is my current favorite horror comic book.

I love tons of the new genre work in print. Julia Gfrörer’s work, that really gets under my skin. I love Julia’s comics and chapbooks, they're all terrific. I also love Junji Itō's work, which is very successful. We don't have comic shops around here anymore but we have Newbury Comics, which is a CD/tchotchke store that has a comic section. They have every Junji Itō work in there for sale. I mean manga eats up a fifth of their floor space right now, and that's mainstream. Junji Itō is mainstream.

And you're right, much of it is safe, but I came into horror when I was a little kid and because there was stuff that was safe for me to see, I could cut my teeth. As I grew up, with the exception of the underground horror comix and some of the black & white horror comic magazines, horror comics didn't grow up with me. Horror literature and horror cinema did. I grew up into the adult horror that already existed. And there was some work that we would consider safe enough that it was read in schools, like Edgar Allan Poe, that became even more fucked up when I re-read it as an adult, then I went, "Oh my god, I had no idea."

I don't despair. I take a lot of heat from friends. I love the extreme horror waves we’re experiencing, but I also keep tabs on and enjoy much, if not most, of the mainstream horror fare amid this genre boom we’re in. I lost one friend on Facebook because I liked Twilight. I loved seeing the Twilight movie because it is a mainstream horror movie aimed at pre-adolescent girls and their mothers. [Laughs] I have waited all my life to see a vampire movie in a packed theater, because it sure wasn't packed when I was going to see Dracula Has Risen from the Grave when I was what - 12 years old, 13 years old.

I'm okay with all this. I try to catch every horror movie I can. I have given up trying to read every horror comic out because thankfully there's too many of them, Jason. You're right, it's not just a moment, we're in a boom cycle right now. I gave up trying to read all the literature because there's so much new horror work. When you bring in print on demand horror…

And what do you call horror anymore? Should I be reading Bigfoot sex novels? Should I be reading-- [Laughs] could I stomach another zombie novel? I say that as somebody who wrote a zombie short story or two that's been published. I find it all invigorating. I was worried when I was younger that I would become one of those old geezers. I grew up reading Famous Monsters of Filmland, where the whole thing was, Universal Monsters are best and these gore movies are awful. And I didn’t buy that then, and I don’t buy that now. Hell, I love all of it. To me, the adventure of being alive right now at the age I’m at is, oh my god, the best horror shit that ever existed, it exists right now and I want to sample all of it. I want to experience the work that goes too far. I want to experience the work that's okay for my grandkids to see.

My grandkids, who are ages 10 and under, are watching cartoons that are considered safe and normal for them, that have incorporated the entire fucking H.P. Lovecraft Cthulhu mythos into these cartoon universes. It's all dark dimensions and demons from the other side, and it's like, holy shit, this is the stuff I was reading when I was reading about-- Cry Horror! by H.P. Lovecraft, here we go, I happen to have it right here. [Holds up the book, laughs] Now, it's part of the cartoon universe. That Pixar/Disney film, Strange World that just came out, looks like a Richard Corben underground comic. I love this stuff!

Does that mean you won?

I wasn't out to win anything. Yes, sure, when you put it that way, Jason. Let me do a victory lap around the basement if I can do it without hurting myself. Taboo did what it was supposed to do, and when I got done with Taboo, Tyrant was the next most important thing to me because I didn't feel like I had to prove anything anymore.

Charles Burns didn't need Taboo. Mainstream book publishers are fucking publishing Charles Burns, German and French publishers are publishing Charles Burns. I love everything Charles Burns does. But he didn't need a vehicle like Taboo. Charles Burns spring-boarded out of RAW into the world, into doing covers for Time Magazine and the New Yorker. But Taboo definitely needed Charles Burns, in my mind.

I'm pretty sure you're still the only one to publish that story, though.

Oh, yes. You mean his first comics story, the photo-roman?

You published his very first story, 7 which is unlike anything else he's ever done.

I agree. There is part of me—and this is the axe-grinding part of me—I'm reading all these books, and I even bought one of the books that went with an art exhibition of the alternative comic scene of the '80s [Raw, Weirdo, and Beyond: American Alternative Comics, 1980–2000, edited by John McCoy & Andrei Molotiu; McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2022]. Nobody mentions Taboo. Nobody. It's never mentioned. Weirdo, RAW, Love and Rockets. There's like this holy body of work and nobody talks about Taboo. Well, that's okay. I’m used to it, I get it. You know, when horror really works, it's the bastard child nobody wants to talk about.

Is there part of you that's pleased to know that Taboo's legacy is in dusty bins somewhere that some kid will stumble upon?

Yeah! Also, if you ever measured those books that you just held up, Jason, we designed Taboo to not fit in any bag or white box. So that it would have to stay on the shelves and in those dusty bins. [Chuckles]

I mean, I wish it was still in print. I wish that the people who contributed the work were still profiting off it. Some of it is still in print, From Hell, Lost Girls, Jeff Nicholson’s Through the Habitrails enjoyed a proper Dover Graphic Novel edition. But it had its time. Swamp Thing had its time, it's really gratifying to hear what you said earlier about the work we did. That's for you to say. I can't look back at it and assess it, but we had our time and we gave it our best shot. If I die tomorrow, what a hell of a ride I had, and I really gave it my best.

You said earlier, I had three career arcs in comics - well, no, I also taught at CCS for 15 years, had an active hand in working with and teaching all I could to part of a whole new generation of creators, and that’s as vital a part of my life in comics as anything else I did. But, again, I get it: only our CCS alumni understand what we did, what that experience was, its importance - to them, personally and professionally, to the field of American graphic novels, which will (as the Kubert School proved over time) become increasingly evident as the new work by those who came out of CCS make their respective individual and collective marks. And now, post–CCS, will I be doing more? I hope so. Whether anyone notices or cares or not, well, I’m keeping busy. It’s still working for me. I can’t worry about much more than what I can do.

I've taken a lot of lumps in my life. I'm not fast enough, I'm not professional enough, I didn't get enough done. I'm too distracted. My friends that are into horror fiction think I don't do enough horror fiction. My friends that are into comics piss on all the work I do that's not comics. My friends that are into horror movies wish I was making horror movies. I've got all these crazy interests, they go in multiple directions, I get work out all the time, I'm having fun, I got a good life, I feel very fortunate.