In this series of interviews, I want to explore the question: What makes Toronto a great comics city? Instead of looking for a definite answer, I want to show the various elements that constitute the Toronto comics community. While it is true that there are seminal institutions and figures in its development, the contemporary Toronto comics scene is proof that great art does not come from a lone genius but from a community.

This is the second installment of my Toronto Comics Today series of interviews. (Chris Butcher is retroactively the first.)

***

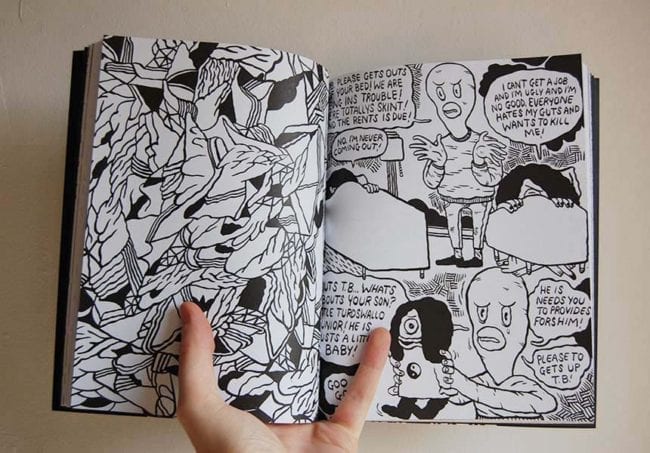

Patrick Kyle has been making some of the most innovative and distinctive comics in North America for several years, most notably in his graphic novels Don’t Come in Here (2016) and Distance Mover (2014). Kyle’s oeuvre explores space as the main force for the propagation of narrative. You could also just enjoy his beautiful, surreal, out-of-nowhere, and often abstract images, as well as his perfectly matching non-sequitur dialogue.

Kyle’s new book, Roaming Foliage, is his most innovative work yet in page design, style, and structure. He is already significantly influential among young cartoonists.

I want to start with the excellent Distance Mover T-shirts. It is the best T-shirt in comics. It is super comfortable. The cotton and the texture is terrific.

I chose those shirts especially because I love that type of shirt. Annie Koyama’s partner Scott has like three of those Distance Mover shirts. He wears them all the time. [Laughs.]

I was surprised when I finished Roaming Foliage. I had followed it from [your zine series] New Comics, and it had looked like the narrative was intuitive and there had been no considerable plan. But it turned out to be a profound and complex narrative. I think that’s the most advanced narrative structure you’ve ever used. Did you plan it from the beginning?

No, Roaming Foliage was my least planned in recent memory. I started it in 2014 when I returned from the book tour with Michael DeForge and Simon Hanselmann. I was feeling restless and nostalgic for stuff like Mat Brinkman and Brian Chippendale’s zines I read as a student.

I wanted to make something that was more visual and a little more energetic than what I had been working on. I think I was deep into Don’t Come In Here already at that point. I just had a desire to create some zine-type work that was visually different from what I thought other people were making at the same time.

So my approach with it was to make quick drawings and half-write the narrative. I’m sure you noticed some of the lettering is hand-rendered, and the rest is a typeface. I’d leave myself spaces and fill in dialogue later. I’d scan all these bits and pieces and collage them together on the computer. There’s one background that’s used over and over again like on almost every page, but sometimes it’ll be reversed or in a grid or torn apart and rebuilt differently.

I was actually going to ask you why the backgrounds of Roaming Foliage are collages.

It was a desire to experiment with something unusual-looking. I intentionally created compositions on the computer that were garish, ugly, or asymmetrically balanced. [I think these images are] challenging to look at and absorb for both myself and an audience. That's what I like about comics as a medium, that you can present a lot of information to someone and they can take their time to figure it out. In films or music, there’s only this specific—

Time-based?

Yeah, so in contrast [to time-based media like films or music, in comics] people have an infinite amount of time to look.

Is it just the same one image in the background of the entire book?

Yeah, it depends on the page. I mean there’s this one central background and it’s like a drawing of a forest, and it appears definitely in the first half of the pages and then it appears more sparingly as it goes on just because I was bored and wanted to challenge myself in some ways.

For a lot of readers, that’s a hard to detect detail unless you take care. You said that comics are good because people can take their time on each page. Aren’t you worried, because a lot of people just read the dialogue and then go to the next page and look for the plot -

For a lot of readers, that’s a hard to detect detail unless you take care. You said that comics are good because people can take their time on each page. Aren’t you worried, because a lot of people just read the dialogue and then go to the next page and look for the plot -

If that’s the kind of comic they are looking for then maybe my comic is not the comic for them. [Laughs.] I’m not making it as a pitch or a script or anything. I don’t want to court that kind of audience. I want people to take out their book and enjoy it as a visual object, maybe even more so than what the narrative is offering.

You wanting readers to take time reminds me of one thing I loved about Don’t Come In Here and Roaming Foliage. There are several sequences where you show the passage of time and there only little differences between each image, for example when Rotodraw goes into the hole, the sequence of images. It’s rare for comics artists to show how time passes and how things change in such ways. It’s one of the things that I wish people are noticing from your work, that it’s not only beautiful drawing but there’s more to it.

I think that comes from watching 2001: A Space Odyssey or especially Lynch films, where he creates these tedious moments that happen for a lot longer than they maybe should. It tests the audience’s patience and I like doing that as well, especially that sequence where Rotodraw is descending into his chambers. I was thinking how long can I make this before people are like, “Oh my god, this is still happening?” Also, it was just a lot of fun for me to draw those individual areas and imagine that space and how it exists. I like that part of the book.

There are enlarged and modified images in not only the background but also in characters and places.

I like the way the drawings look, like small drawings blown up. You can see all of the character and nuance in the linework. I did a lot of that when I was a college student. I’d do acrylic matte medium transfer technique that I was known for in my early illustration career. It would involve photocopies. I’d do tiny, tiny drawings and then blow them up big and paint them.

I think it makes the line and the drawing look a certain way that wouldn’t be possible had I just actually drawn it from that 1:1 scale. I think it looks cool [Laughs.]

Is post-production using computer important in other works too?

No, not necessarily. For a long time, I was very anti-computer manipulation. All of my illustration work was completely analog, and all my comics were analog. I only used the computer to clean up black and white drawings.

But I have been way more comfortable thinking of the computer as just a tool, not as a shortcut or cheating or anything anymore. [Laughs.] I’ve become way more accepting of it. I think it’s my only book so far where there’s not original pages, just lots of bits and pieces. All of the originals only exist in the computer.

Aren’t you worried about original art sales? [Laughs.]

I don’t sell comic pages to anybody. I don’t know if they’d be interested in that. [Laughs.]

Your work is surreal or sci-fi, even when it’s about real lives like Don’t Come in Here. Roaming Foliage and Distance Mover are more evidently sf.

I love science fiction. I like making those types of works, creating them in a way that’s different from what currently exists. Everyone has certain idea of a fantasy story, like involving like an elf or some creatures. I have an interest in taking those existing tropes and putting them into my world.

Every book of yours has a very distinct style. Do you try to come up with a new style every time?

There was a time when I felt like I was actively pushing to draw in new ways, but it doesn’t always work like that when you are forcing it. It comes out feeling static or strange looking.

So I draw a lot. I turn my brain off, and I fill sketchbooks with drawings. A lot of the ideas come through just doing lots of sketchbook work and doodling.

How did you come up with the idea to make Don’t Come In Here as a collection of short stories?

Both Black Mass and Distance Mover were collections of previously published zines, and I wanted to challenge myself to create a book. It just made more sense to me to create it in short bursts and I make all my comics that way now, just because I think it’s easier, both for me to organize the narrative arc, since I am making it off the cuff and maybe it’s easier for an audience to digest it as well. I like taking those breaks when the story needs to sit with what happened for a minute. It’s a chapter break, I guess.

Since Don’t Come in Here, your books have the grey newspaper-like light paper stocks. It looks similar to the paper your zines are printed on.

I don’t know if it’s the same paper technically, but it’s similar. All the issues of New Comics that have the Roaming Foliage stuff in it, they were all in newsprint.

I love the paper, but I am worried because it’s newsprint and it doesn’t last that long!

Everything is fleeting. Every book will some day be dust. [Laughs.] So it doesn’t matter. [Laughs.]

How did you decide to print them with not just zines but in books? That is a huge decision.

For Don’t Come In Here, for the entire process of drawing the book, I had this idea in mind of what I wanted to finished product to look like. It was like that of a cheap novel that you would buy at Rexall or whatever in the romance section. I wanted them to feel fleeting as an object. Just simple. Something you can jam into your bag or your back pocket.

I think that the paper is very tactile. It feels really good. A lot of the paper stocks that had been presented to me just didn’t feel right. I wanted something different for the book. I just really really liked the aesthetic of the paper. Annie suggested that we continue with it. So all of my books are being printed like that.

I have been frustrated with reviews of Don’t Come In Here. People say, “Oh, it’s about being alone and sad in modern society!” Yes, it is, but also there’s much more-

People will either get it or they are not going get it. It doesn’t bother me.

I mean, your work is unique in how you present your ideas visually, but I think you don’t get enough credit for it. I worry that critics don’t have enough or good understanding. It's sad because we should cultivate this kind of work that studies visual language and representation. I want to see more work that takes care of these aspects of comics.

Thanks, I appreciate that a lot. I think a lot of people who follow me are more interested in me as an artist or an illustrator, and maybe don’t really know me for my comics work, and I don’t often feel like a comics artist. I’m part of that world, but I feel like most of the artists that inspire me are making fine art or illustration and are not completely comics work. Honestly, I haven’t been reading a lot of comics recently. I feel a little disconnected from the comics world, but also it doesn’t bother me.

I was wondering if you get frustrated—

No, not at all. I’ve been really lucky in my career. I’m not the most famous or popular artist or whatever but I don’t know, who is? It doesn’t matter. I would still be super-lucky to be in this situation I’m in.

I have such an amazing publisher, mentor, support from Annie [Koyama]. I’ve just been really lucky in the school I got to go to; the space that I live in; the peers I came up at the same time with. I feel so thankful for all of that. But if that support system wasn’t there, I’d still be doing all this stuff. It'd just be in a different way I guess. I don’t know if I would’ve found a publisher necessarily if Annie hadn’t known me.

A lot of young cartoonists are influenced by you, but not a lot of them acknowledge it.

I don’t know [Laughs.] It’s a different time. I am influenced by a ton of people, and it’s pretty evident. It’s like a weird thing to speak on. I definitely see young artists who are inspired by me, and I think it’s really amazing and flattering and I am glad that I’ve been able to have that kind of reach as an artist.

It doesn’t bother me. I always feel excited about embarking on new challenges, and I like working in different styles. So if someone sort of takes a specific aspect of my work, they can have it and I’ll come up with something else.

I first saw your work online in around 2013, with the Distance Mover zines. I was surprised when Koyama Press announced that they were going to publish it because I thought it would not sell well. I thought it was too avant-garde.

Yeah, I was worried about that too. Even in our first meeting for the book, I told Annie, “We should keep the first run of this book low, it’s not going to be popular.” And she was like “Shut up, I’ll take care of this.” [Laughs.] Not in those words but [laughs] yeah. That book went into a second printing quickly.

Wow!

Yeah, maybe because I had warned her and she was like, “Okay, maybe I won’t make a lot of these.” [Laughs.] It had to go into second printing quickly. It was really cool. I think that’s actually my most popular book.

Interesting!

I think it’s because although it’s visually a little daunting, the narrative is straightforward.

Black Mass is your only book that is not published by Koyama Press. It is self-published.

That’s right. Because I didn’t think any publisher would even consider publishing it. I think that is probably accurate.

Your style has changed a lot since Black Mass. Between Black Mass and Distance Mover I see the most substantial gap.

I consider Black Mass and Distance Mover to be my two juvenile books. My early career books. I find that they are connected stylistically and rhythmically. The reading of them is similar. The style changes a lot through the book Black Mass also.

I started Distance Mover a couple of months after I finished Black Mass. It wasn’t a conscious change. I just got the risograph machine at that point. I wanted to create the page layout that would work simply for doing two color separations. So I decided I would have no object to touch each other. Everything on the page is a separate entity so that I could just easily cut it out of the computer. It’s the same as Black Mass, but it omitted any background idea. In Black Mass it was about filling up the space with lines.

Did you meet Annie Koyama after you printed Black Mass?

No, I met her before, maybe even before the first issue of Black Mass or during the creation of the first issue. She came to our launch for Wowee Zonk 2.

What year was it?

It was 2009. The first issue of Wowee Zonk came in 2008. It was just me, Ginette [Lapalme], and Chris Kuzma. We got a small grant from OCAD [Ontario College of Art and Design], our school to print it.

For the second issue we worked with a newsprint press we found out from Jesjit Gill [from Colour Code Printing.] He'd been doing a free paper called Free Drawings through them. We asked a bunch of artists whom we went to school with to contribute. We asked Michael DeForge to contribute as well. I think it might be one of Michael’s first published comics — I don’t know if that’s 100% accurate but I think it was one of Michael’s first things. We were just graduating from OCAD at the time and we finished the issue and had a ton of artwork that we wanted to show in excess of all the work for our grad show. So the same week we graduated we put up an art show and launched the magazine at a gallery on Bathurst street. We felt excited and proud of ourselves that we had done all that.

Did you like OCAD?

Yeah, I definitely feel I needed to go to art school. OCAD is responsible for me meeting Chris Kuzma and Ginette. I grew up in the suburbs, and there was no culture available to me. I didn’t know anything interesting artistically until I was in college.

Why did you choose illustration at OCAD?

In high school, I wanted to draw comics as a career. I was looking at the different programs on OCAD website, and illustration seemed like closest one to what I want to do. While I was at OCAD, I got excited about the opportunity of becoming a commercial artist and using my skills in that way. I think comics took a back burner for a certain period of time while I was at school. Then when I was in the fourth year I started drawing comics more seriously again. I drew the first issue of Black Mass as a student.

I heard artists hate this question, but readers love this question! What’s your next project?

That’s easy. I’m working on it right now. It’s called The Death of a Master. It’s a full-length version of a 22-page comic I printed in 2017. I had no intention of continuing it, but I was just thinking of what I was going to do next, and that story just had a lot of opportunity in it for world-building. It seemed like it would be a lot of fun.