This interview with French dessinatrice Catherine Meurisse was conducted via email in the second half of 2016. Meurisse's German publisher Carlsen was about to release the translation of Lightness, wherein she processes her feelings as a survivor of the Charlie Hebdo killings on January 7, 2015. Because of my poor French, the questions were asked in English, answered in French, and then translated into English by Thomas Ragon, editor at Dargaud, the French publisher of Meurisse's work. This translation was then proofread by Marc-Oliver Frisch. - Oliver Ristau

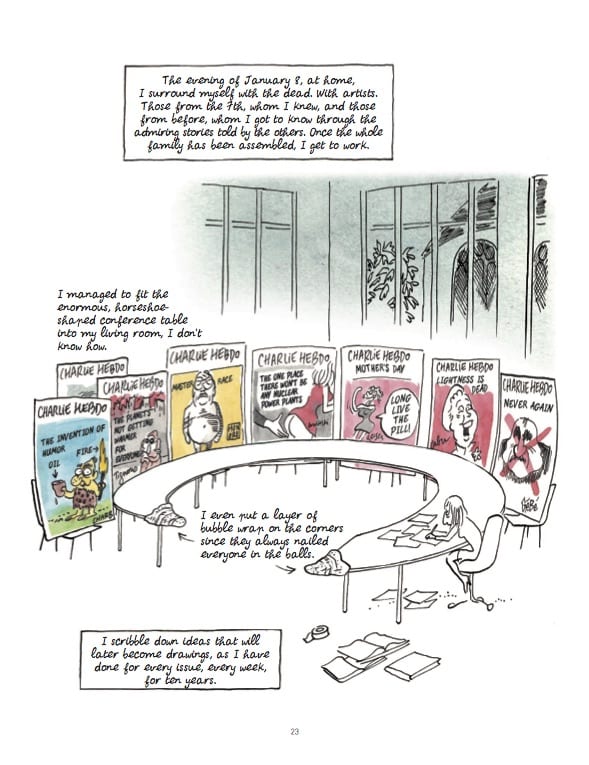

Oliver Ristau: Do you sometimes feel like Niobe? Seven artists - killed on January 7 - are depicted on page 23, with you being shown in a still protective but also stranded manner.

Catherine Meurisse: Correction: On page 23, the seven artists whose drawings we see were not all killed in January 2015. From left to right: Charb, Tignous, Honoré, and Wolinski were killed on January 7; Reiser died in 1983; Cabu died on January 7; Gébé died in 2004. They are important and historic Charlie artists. After the attack, I summoned them mentally, like one summons friendly ghosts, to help me get back to the drawing board. I don’t feel like Niobé, as I’m not their mother [Niobé saw her children dying under Apollo and Artemis’s arrows]. It’s more the contrary, they were like fathers to me. My position/posture at the drawing table, encircled by these spiritual fathers, is more a focused than a disoriented one. I represent myself regaining my strength thanks to their imaginary and posthumous presence around me, at the same table. It’s an oneiric scene, not a mythological one. January 7 is not a myth; it unfortunately really happened.

What bewildered me most during my reading of La Légèreté were the panels depicting the previous backgrounds both of you and the brothers Kouachi in an overlapping way. At the beginning the panels were separated from each other, the final panel at the bottom of the page shows you and the killers using the same slogan, "En route pour le 'bête et méchant!'" while heading out into the world. Technically, that's something you can't easily achieve by using any other medium than bandes dessinées. Content-related it's setting the "career entrant" of the murderers of your colleagues working at Charlie Hebdo on the same level with your beginnings as an artist. How cynical is that?

Comics allows everything, representing everything, telling everything, in that it’s unique. For me, this imaginary scene, staging the Kouachi brothers and me as children, is more ironical than cynical. It’s the only moment in La Légèreté where I condescend to notice the killers. Those two guys were as old as I am. Why did they tumble into violence and not me? This question occurred to me, but I chose to not reply to it, I didn’t want to draw a psychological portrait of these men I despise. I simply put them in the "stupid and mean" category. When using the locution "stupid and mean," I’m ironically playing with the words: It used to be Charlie’s satirical-magazine ancestor Hara Kiri’s catchline, and it [the locution] pointed to free, unbound, and anti-conformist humor.

The topic is explored further when you tell the reader about the experiences made during your residency in the Villa Medici. There are two graffiti artists residing in the studio of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, which are represented as performers that seem to have an infatuation with extremism. For example, after posting some of their works on social media they get insulted as "Daesch." I find it kinda funny to juxtapose them with Ingres, who's classified as a keeper of tradition within the French artistic canon, but also anticipated modernism in several ways by using incorrect perspectives etc. And your fascination with Caravaggio, who wasn't only a redefining artist during the times of early baroque but also had been banned from Rome because of manslaughter. Have you, while trying to get salvation from an experience of enlightenment from Stendhal syndrome, maybe fallen victim to a kind of post-Stockholm syndrome instead? Do you believe in the destruction of art to create something new and can it be read as a statement on that?

The topic is explored further when you tell the reader about the experiences made during your residency in the Villa Medici. There are two graffiti artists residing in the studio of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, which are represented as performers that seem to have an infatuation with extremism. For example, after posting some of their works on social media they get insulted as "Daesch." I find it kinda funny to juxtapose them with Ingres, who's classified as a keeper of tradition within the French artistic canon, but also anticipated modernism in several ways by using incorrect perspectives etc. And your fascination with Caravaggio, who wasn't only a redefining artist during the times of early baroque but also had been banned from Rome because of manslaughter. Have you, while trying to get salvation from an experience of enlightenment from Stendhal syndrome, maybe fallen victim to a kind of post-Stockholm syndrome instead? Do you believe in the destruction of art to create something new and can it be read as a statement on that?

My encounter with the two graffiti artists Lek and Sowat has been important. On the one hand, because they’ve been immediately generous and trustful by lending me the keys to their studio. In that, they remind us that an artist should be open to other artists and allow an encounter. They also embody friendship, which is crucial in a post-traumatic context. On the other hand, I was interested in their status: They were the first street artists to enter the Villa Medici, and incongruous in this institutional landscape. They questioned themselves and their position as artists all along their residency, and their anxiety eventually generated a big artistic audacity I could witness while staying in Rome. The fact they were assigned the Ingres studio was a fantastic wink to art history, which has always been punctuated by fights between academia and modernism. As you point out, Ingres, an eminently classicist painter, allowed himself some anatomical mistakes, and Caravaggio was to me the creator of "the lightness of murder."

Art is full of paradoxes, that’s why it’s vital to us all. Caravaggio holds a particular place in La Légèreté. In the course of my walks in Rome, I used to visit him like you visit a friend. He was fascinating to me in the way his works join together the urges of death and life. I consider him a proponent of the urge to live, and that his paintings stand for me as the impenetrable mystery of beauty. We need this mystery to live. In La Légèreté, I didn’t want to make any statement about art, for the good reason that, after the attack, my memory was damaged, therefore everything I knew about art history had been erased. I was seeing the works as if it was for he first time, I wasn’t cluttered with my old knowledge anymore, I was a virgin to art. This allowed me to be touched right in the heart, to be moved by beauty. Art transforms the eyes that examine it, that put some affects and reflections in it. Facing the beauty, we stop thinking and then we start again to think, but in a different way. This transfiguration is a way to inner peace.

That’s what I was looking for after the attack, and that’s what happened. I say in the book that I’m looking for the Stendhal syndrome, convinced that an aesthetic shock would cancel the January 7 shock, that fainting in front of the Italian beauty would permit myself to live again. Finally and luckily, what happened was the contrary: I fainted, in the figurative meaning, on the day of the attack, and I then woke up again amongst the beauty, in Rome. I did not feel, not for a second, the Stockholm syndrome. In my story, the only persecutors are the January 7 killers, and no empathy was even imaginable towards them. They only deserve contempt, or better, indifference. Ultimately, I only experienced the Meurisse syndrome!

I'm very fascinated by your use of colors as a narrative element, for example the golden glow complementing your heroic pose while applying for the Villa Medici after crawling out of a glooming pond composed of green, black and violet shades. Even more impressive are the opening pages, wherein the colors range from a melancholic setting to a glaring and loud outburst, almost like an outcry. What's behind these coloring schemes, what were your criteria when choosing them?

I'm very fascinated by your use of colors as a narrative element, for example the golden glow complementing your heroic pose while applying for the Villa Medici after crawling out of a glooming pond composed of green, black and violet shades. Even more impressive are the opening pages, wherein the colors range from a melancholic setting to a glaring and loud outburst, almost like an outcry. What's behind these coloring schemes, what were your criteria when choosing them?

There were no selection criteria, because the whole book was made by instinct. As I was saying earlier on, the shock of the attack made me lose my intellectual faculties for a few months. I was unable to think, to form sentences, my imagination was totally blocked, as if some of the parts of my brain had been unplugged. My memories and my culture had disappeared, but drawing and comics require a solid culture. I was terrified by the idea that I might never be able to draw again. I started to write and draw in a large sketchbook in order to not become crazy, to try gathering fragments of myself, emotions in particular. I did not want to let any part of me escape. Colors came to me because they had to: In the opening scene, in front of the ocean, I chose dry pastels because it couldn’t be anything else. For the pond scene, it couldn’t be anything else than watercolor. I opened up some color boxes randomly, instinctively. This graphic disorder at the time matched my inner disorder. La Légèreté is a huge gathering: There are the dead and the living, black and color, writing and drawing, sadness and humor.

Have you ever heard of Karl May's fictional Native American hero Winnetou, who is very popular in Germany? I'm asking because the pun you made about Edith Piaf was changed in the German edition of La Légèreté into a pun on Winnetou.

No, I didn't know about him!

Walls seem to play an important part in your BD. Sometimes they appear suddenly in your way, straight out of nowhere, other times you're moving through them like a phantom. What does it mean, especially when you're located in an art gallery full of hollow frames and ending up with Edvard Munch's The Scream as the only painting being visible? Could it symbolize the wish to vanish in art but being unable to do so?

Walls seem to play an important part in your BD. Sometimes they appear suddenly in your way, straight out of nowhere, other times you're moving through them like a phantom. What does it mean, especially when you're located in an art gallery full of hollow frames and ending up with Edvard Munch's The Scream as the only painting being visible? Could it symbolize the wish to vanish in art but being unable to do so?

My wish was not to vanish in art but to traverse it and get out of it with an additional thought or feeling. That’s the case with the dreamlike sequence with Munch, which immediately follows the sequence of the morning of January 7 and which represents my swaying into the inexpressible. I’m striding along an art gallery with empty walls, art has completely vanished from the picture rails, culture has just been murdered. I cross through the walls and end in the Munch’s painting The Scream. Munch’s Scream is the scream I didn’t succeed to express on the 7th. Munch therefore helps me to express the inexpressible, and I believe this is the function of art in general. There is this intention all over the book: In Rome, especially, I go to meet the works, antique marbles and paintings, in order to find help, a new way of thinking, a breath of life, a rebirth.

I appreciated the way you made use of initial drafts by incorporating them in your story. You took parts previously published in other magazines, as well, for example the sequence set at the psychiatrist that originally appeared in the Charlie Hebdo issue released one week after the attack. How did it feel to revisit these older episodes, how did you conceptually arrange the older stuff with the new content?

I tried to collect all the pieces that could help me to rebuild my identity as a woman and as an artist. Hence, my notes from the "Survivors Issue Wrap-Up“ and the drawings I made for this unfortunately exceptional issue are inserted in La Légèreté, such as the strip where I draw Elsa Cayat, Charlie’s psychoanalyst, analyzing her own murderers. It’s a way to make her eternal and to show her intelligence’s triumph beyond her death. The strip showing me on a shrink’s couch [page 88] was made in November 2015 for Le Monde. To me, it looked eloquent enough, I had nothing more to say about the November attacks. La Légèreté is a book about reconstruction, where I put the pieces back together. I don't want to lose anything anymore, having lost so much already.

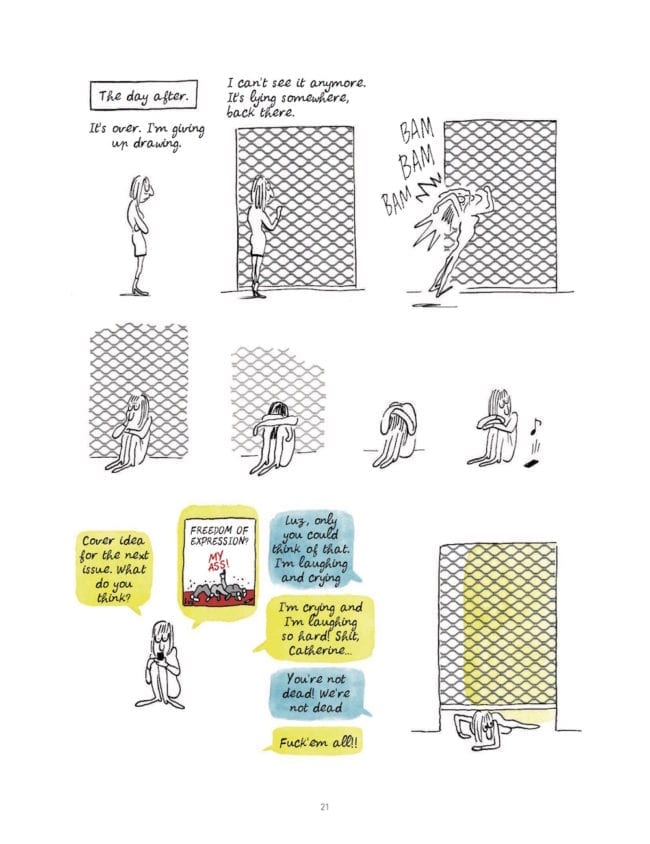

You have a very idiosyncratic way of doing page arrangements, by getting rid of panels and using coloring in unusual and unlikely ways; page 21 would be an outstanding example for that modus operandi. The portcullis/grid background is mostly defining the space while the coloring, finally, is used to lock out the conversation between you and Luz behind that grid at the bottom of the page. Is this a meta-commentary on the medium's inherent boundaries, maybe?

You have a very idiosyncratic way of doing page arrangements, by getting rid of panels and using coloring in unusual and unlikely ways; page 21 would be an outstanding example for that modus operandi. The portcullis/grid background is mostly defining the space while the coloring, finally, is used to lock out the conversation between you and Luz behind that grid at the bottom of the page. Is this a meta-commentary on the medium's inherent boundaries, maybe?

The graphic treatment of this page looks like the condition I was in when I drew it. Alone, unable to stand up yet, I’m crawling under the obstacle. That steel grid did exist, it’s the one which was pulled down on the premises where I was sheltered – you can see it on page 17. Afterwards I used it as a metaphor: It’s the wall behind which lays my drawing, which temporarily makes my art and my profession unreachable. The color underlays and separates my texting back and forth with Luz, yellow for Luz’s texts, blue for mine. One could also see it as a coloring of language, a beginning of color, therefore life, as the traumatized language recovers.

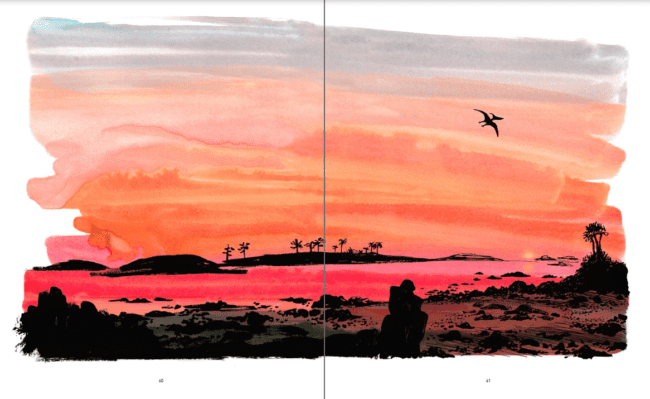

On page 61 there's a pterodactyl flying into the setting sun. Do you feel like an endangered species?

No, I didn’t identify myself with the lost species pterodactyl. I made it fly over my head, it’s alone in the sky and I’m alone on my rock, each of us in our own solitude. This scene is a report of a vision I had while staying on a British island to which I escaped a few weeks after the attack. Absorbed by the setting sun, whose light made the craggy landscape very mysterious, I lost my sense of time and I thought for a minute that I was back at the beginning of the world, in prehistory, before inhumanity, before the Kouachis’ acts of hate. Trauma makes people tumble out of human time, it can take us back to ancient times, it's barely possible to describe. It’s very weird to experience. I tried to communicate this new and incredible feeling. I put it on paper in order to preserve it, and to not lose my mind.

Did you find the solution to Honoré's rébus? And is "Operation Revanche" a thing that really did happen?

Did you find the solution to Honoré's rébus? And is "Operation Revanche" a thing that really did happen?

Unfortunately, everything in La Légèreté is true. It would have been obscene and absurd for me to invent anything, as the reality was bigger than fiction. The "Opération Stencil" accomplished with Honoré’s daughter and Sigolène Vinson happened exactly as depicted. Hélène Honoré did pronounce the words "vital expedition" in front of the Bataclan, on which there would be a deadly attack two days later at the same time of day. Life and death never stop to cross each other in my book. The solution to Honoré’s rébus has not yet been found, though we roped in great minds such as the Fields Medal mathematician Cédric Villani! Honoré keeps his mystery, as he should. He would laugh a lot seeing us all try in vain to decode his rébus like you try to decode a treasury map.

You re-drew works of famous painters for the benefit of your story, Manuele Fior worked in a similar way for his Variations d'Orsay commissioned by the eponymous museum. How did those works help you to get on with your story, art-wise? Were they influential to your style habits? Were they essential for the healing process you tried to achieve by re-appreciating the world of art?

I’ve always been making comics alongside my work as an editorial cartoonist, and art and literature have been at the core of my comics for almost ten years. In Mes hommes de lettres ("My Literature Men"), I tell, with humor, the history of French literature, from the Middle Ages to the present. In Le pont des arts ("The Bridge of the Arts"), I look at the turbulent friendships between painters and writers: Cézanne and Zola, Proust and the Impressionists, Diderot and Greuze, Picasso and Apollinaire, etc. In Moderne Olympia, co-published by the Orsay Museum (the book precedes the one by Manuele Fior), I change the museum into a Hollywood studio and I revisit art history as a musical; characters from paintings become actors and rivals, like in West Side Story. Manet’s Olympia is my protagonist, and the book is also a reflection on the status of the woman model in art. I always liked to belittle the great artists, not just for the fun of doing so, but in order to invite them into our lives and share their treasures unreservedly. Until now, artists and writers had been actors to me, and I would put them on a stage. In La Légèreté, for the first time, I’m joining them on stage, I’m talking to them, I’m going through Caravaggio’s works, I’m walking the Roman Forum with Stendhal. I’m calling them for help, literally. And what is wonderful is, they help me instantly and generously. Art is allowing me to meditate, I can face the violence of the real world when I contemplate the violence of Caravaggio’s paintings, I can think about death and about wounds when I contemplate the marble sculptures in which I believe I see the bodies of my murdered friends, I can find peace when contemplating the chaos inherent in beauty. Art allows me to give some meaning back to my life.