A full house turned out for the book launch of cartoonist, writer and sometimes television celebrity Ed Subitzky's long-awaited first anthology of work at Rizzoli Bookstore in New York City on October 13. The collection, Poor Helpless Comics! The Cartoons (and More) of Ed Subitzky (New York Review Comics, 2023), gathers many of the best comics and text pieces Subitzky contributed to the National Lampoon over the lifetime of that magazine (1970-98). An in-depth interview with Subitzky by cartoonist Mark Newgarden, the person responsible for bringing the project to NYRC, is interspersed throughout the book.

It's a wonderful collection, and deceptively dense, given Subitzky's ultra-spare art style. As Frank M. Young wrote in his TCJ review of the book, "Sometimes the enormity of [Subitzky's] concepts and disciplines makes time stand still; your brain, so accustomed to the predictable, is rocked and socked as you take in these quodlibets and logic puzzles. They are designed to release you from mundane thinking. Subitzky’s work is demanding but therapeutic, like an intense massage. These pieces don’t betray their vintage: they are fresh, bracing and modern in their avant-garde-yet-humble approach."

Subitzky has long been one of my favorite cartoonists; his Dada-tinged minimalist comics set my brain on fire when I first encountered them as a teenager. I'm not alone in having waited impatiently for decades for someone publish a collection of his work; it joins NYRC's 2021 publication of Shary Flenniken's wonderful Trots and Bonnie in preserving the legacy of the work done by amazingly gifted cartoonists during the best years of the Lampoon.

Meeting Subitzky and his lovely wife Susan Hewitt at the book launch was an honor. To me and many others, he remains one of the most singular figures in comics history, and the new book should open his brainy, bizarre take on the world to new audiences. It truly deserves the attention. The 80-year old Subitzky was joined at the event by Newgarden and filmmaker Owen Kline (of 2022's Funny Pages) for a discussion about the new collection, as well as his career as a cartoonist, a successful advertising copywriter, and a regular performer on various David Letterman TV shows.

The following article is not strictly a transcript of the Rizzoli Bookstore event. Rather, it combines questions by Newgarden and Kline—and questions from the audience—with several questions of my own, both asked at the event and later, inserted where relevant to the topic.

-John Kelly

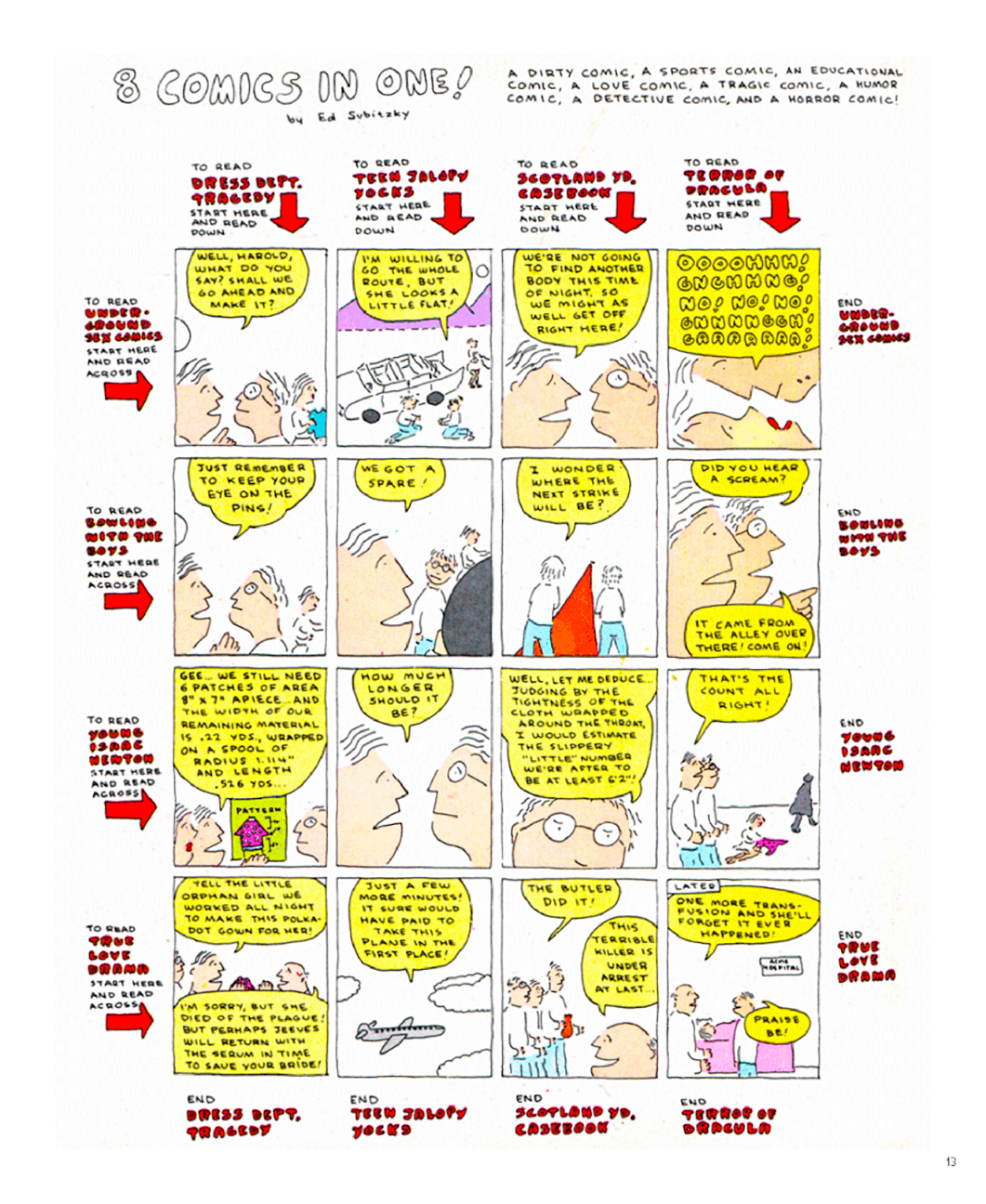

MARK NEWGARDEN: I saw Ed's comics at the right age... 12, 13 years old, and they really changed the way that I thought about comics. What kind of a brain gets us to "8 Comics in One!"?

ED SUBUTZKY: You want me to talk about "8 Comics in One!"?

NEWGARDEN: I want you to talk about your brain. [Laughter]

Oh, my brain. [Laughs]

NEWGARDEN: How you came to comics.

Well, that's just my brain talking about itself. My brain talking about its brain. How I came to comics... well, I have always adored comics. As a kid I bought every one on the newsstand that I could find. And I was always drawing and making little tiny sketches and things like that. To the consternation of my parents, who didn't understand and who wondered what kind of a weirdo they were bringing into the world. And then when I grew up a little bit and got out of college, I took a course at the School of Visual Arts, and that course was the best thing that ever happened to me, at least as far as cartooning goes. I had two marvelous teachers, Bob Blechman and Charles Slackman, and I loved that class so much I took it for 12 semesters. [Laughter]

And so, I started submitting to the Lampoon, and I started fiddling around with the comics format to try and see what I could do with it -could I stretch it, could I bring it in and make it a little stranger, and stuff like that. I'm saying all of this in retrospect, like thinking back and giving myself reasons for having done something, but the fact of the matter is, it was just fun. I just wanted to sit at the drawing table and play around, and it was great that the National Lampoon at the time was using this stuff. And that's it. I feel a little bad, because the way I work, there's not a lot of story. Again, it was just: sit down and have some fun, and "Oh, this popped out." And two weeks later, "Oh, and this popped out of me." And, "Where did this one come from? Oh, that popped out of me..." I can't give you any overriding theme that my work represents or anything like that. Maybe there is one, and maybe somebody here can figure it out, but I wasn't able to.

NEWGARDEN: I took that same SVA class a few years after you. When I took it, Slackman and Blechman very much played good cop/bad cop. Was that your experience?

Totally. [Laughter] Slackman was rough, tough and 'tell it like it is.' If he didn't like something, you knew he didn't like it. Blechman was soft and gentle and sweet, and he would just tip toe up to the fact that he was having a problem with what you did. So you really did get the good cop/bad cop treatment.

NEWGARDEN: It was an effective technique.

It was an effective technique. It worked for me, at least.

NEWGARDEN: Did you ever take another class of any kind?

In art? No, I never did. Just that one was all I ever felt I needed.

NEWGARDEN: Why did you stop after 12 semesters?

Because, by the 12th semester, on the first day of class I could see the expression on the instructors' faces. [Laughter] I think they were thinking, "Not him again! What's going on here?"

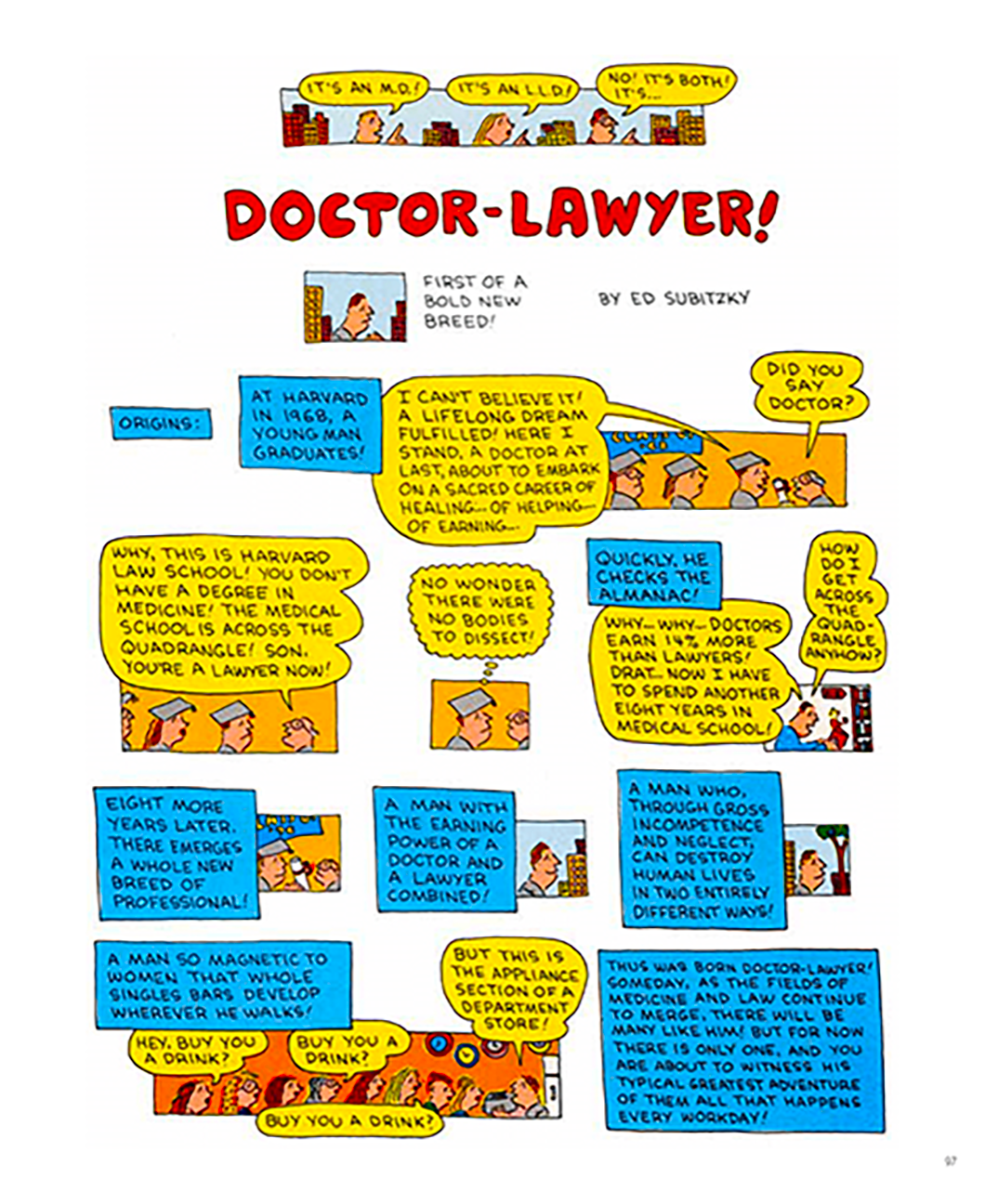

OWEN KLINE: Ed, all of your comics have a certain absurdity in the over-complexity of them. I think of Rube Goldberg and his inventions, things that are overwrought in their complex absurdity. When was it that you came to that particular conception style?

Oh, I think almost right at the start, because I think one of the first thing that I went to do was "Anti-Comics!" in which the comic balloons were people and people were words, or some such crazy thing. And I've always felt that the world was a very strange and complex place. And when you think like that, it's got to drip down into the work that you produce. Again, I don't think there was anything conscious there, that I was trying to do something surreal or anything like that, it's just that I'm a surreal person. [Laughter] I can't help it.

KLINE: Did you find the Lampoon to have the perfect sensibility for you? Bruce McCall, who was also there, also had that certain overly complex, hilarious complexity to his work.

It wasn't any conscious thing. The Lampoon was so open to all kinds of things. I am so grateful that it existed... it was an amazing publication back in the day. And... oh, they would take almost anything. [Laughter] If it weren't for the Lampoon, I probably would hardly ever had my work published. I'd have a little gag cartoon here, a little illustration there, maybe, but nothing substantial. The Lampoon took everything that you could give them. And another thing that was very unheard of in publishing is that they never made changes. You could give them the craziest, wildest pieces, and they never said, "Well, why don't you do it this way... why don't your try this instead and we'll think about it." You just handed in work and that was it, and they published it and didn't mess with it all. That's where the complexity kind of comes in, and they accepted it and then I did more of it. And if they didn't accept it, I probably wouldn't have done more of it.

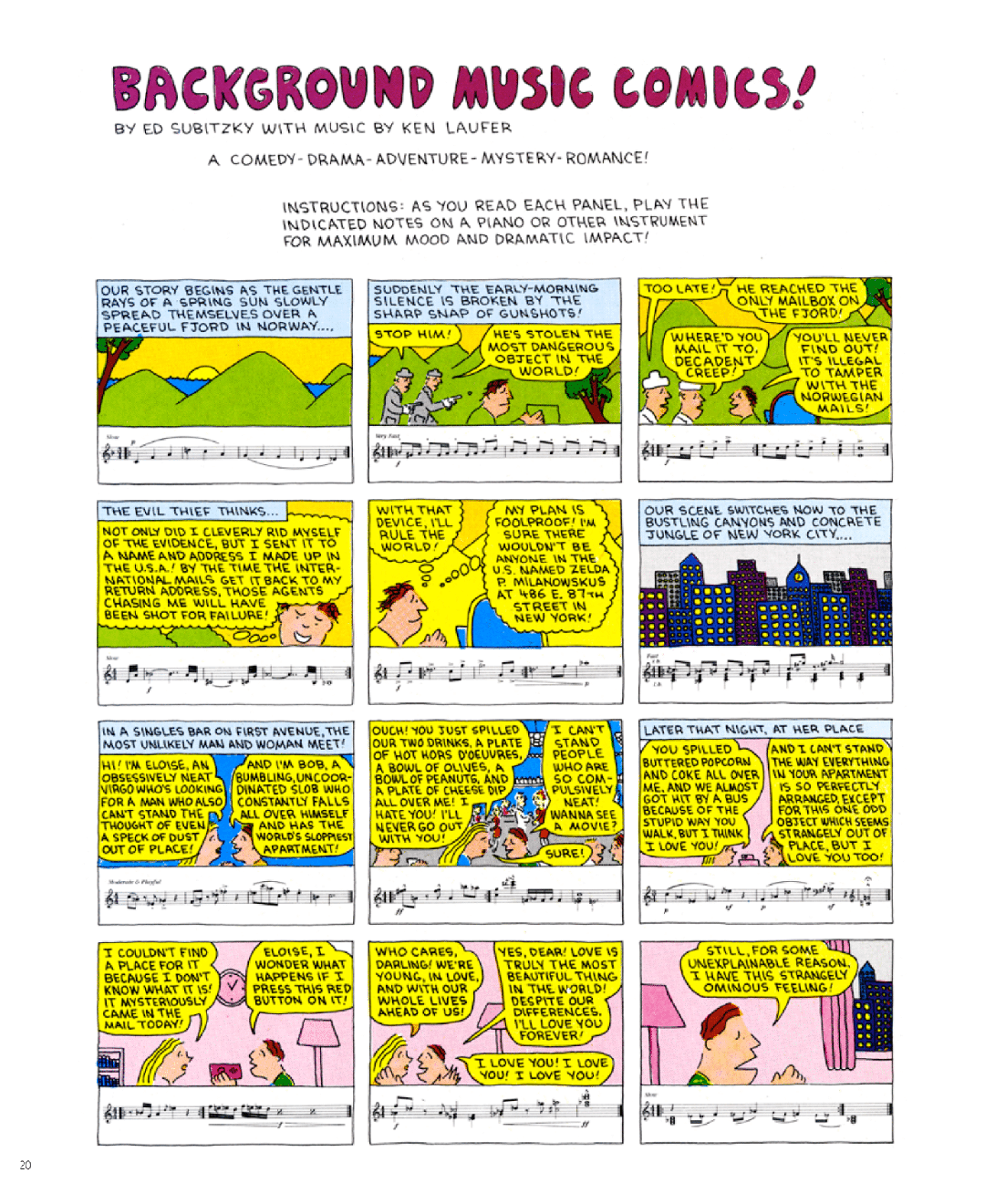

NEWGARDEN: "Background Music Comics!" is one of my favorite comics, or spreads, of yours. You created a strip and actually collaborated with a composer to score your strip. [Laughter]

Yeah, and it came out brilliant. The music is absolutely appropriate for it. Only Ken [Laufer] could have pulled off something like that. [Applause]

NEWGARDEN: Was this ever performed anywhere?

Not that I know of, no. [Laughter] But if you know how to play it on a piano, you can. It's wonderful. Ken used to do a comedy routine with music, and it was amazing. One of the things Ken used to do was, he would play all of the music that was ever written in five minutes. [Laughter] And the darn thing is, it sounds like every piece you've ever heard is in there. He put it together masterfully.

NEWGARDEN: Sounds like a perfect collaborator.

He was.

NEWGARDEN: You became a writer and a contributing editor at Lampoon...

Yeah, I was. I wrote a lot of print pieces for them and "Foto Funnies" and all kinds of things like that. It was a wonderful time for humor back in those days. And I had the privilege of working with such smart and intelligent and funny people. And they taught me a great deal about humor, things that I never knew or understood before.

KLINE: Do any little pieces of humor theory from the Lampoon office stick in your mind?

No, what would happen is there was a terrible restaurant in the [building the Lampoon was in] called Steak & Brew. They would serve beer and terrible steak, and at the end of the day the staff would go down there and they would sit and guzzle beer until quite late, sometimes, and they would come up with the most marvelous material and I would be laughing from the moment I got in there until the time I left. There's one person who I would single out-- I wasn't on the staff of the Lampoon so I don't know a lot about the ins and outs, but there was one person there who I think was the most responsible for the magazine, and that was Henry Beard. And these meetings were rapid-fire, they would just come out with one hysterical idea after another, and then go on to the next hysterical one and then to the next one, all the while eating that terrible steak and drinking that lousy beer. [Laughter]

But unfortunately, I wish I could remember even one thing that Henry or someone else would say during this sessions, but I just don't. I don't remember much anymore. [Laughter]

NEWGARDEN: Is that positive or negative?

The world is getting its revenge on me because I guest-edited the notorious "Old Age" issue of the Lampoon [Sept. 1974], and now my memory is getting a little... "aaaahhhh," so my past is catching up with me.

JOHN KELLY: Henry Beard and Doug Kenney [1946-1980] were the founders of the Lampoon. Did you work with Kenney much?

Unfortunately, I never had much to do with Doug Kenney. There was no particular reason for that, just the way things happen to fall, what issues I was in, what issues he was putting together, and so on. My impression of Doug, for whatever it might be worth, was that he was a very nice person, soft-spoken, endearing, and maybe I can even use the words sensitive and quiet. Since I didn't work with him much, I wasn't exposed on a first-hand basis to his ongoing brilliance. I do seem to remember that he was known for his disappearances: he just wouldn't show up for rather long periods of time, then suddenly reappear and be ready to work on the magazine again. I do want to be careful here, because as I've said, I wasn't on the staff of the Lampoon, just a contributing editor who frequently dropped by their offices, as much as I could! Eventually I think I had some sort of contact with almost everybody, but still - what I'm saying about Doug's disappearances is not based on first-hand knowledge, just a wisp of a memory from so long ago.

I do have one rather sad story about Doug. I wrote two pieces for the [Lampoon's] Encyclopedia of Humor [a 1973 special issue], the "Principal’s Letter" and an "In Memoriam" piece for a student who had passed away, written [in-story] by another student. I tried to make the memorial both funny and sad at the same time, a bit of over-the-top prose that a high school student might write in the face of mortality. Much of the page was taken up with a picture of the deceased, and who did they choose to use as the model for that picture but Doug Kenney? I'm not sure, but I think it might have been a picture of Doug from his real high school days, complete with white tuxedo and a bow tie. Doug told me that he felt spooky about having his picture used for someone who had died. No more need be said.

From 1980 'til 1984, Subitzky made regular television appearances on NBC programs hosted by comedian David Letterman, starting with the morning The David Letterman Show and then the nighttime Late Night with David Letterman program. Subitzky's reoccurring role was that of an "imposter" pretending that he was a famous, or semi-famous, celebrity.

Newgarden: Talk about how you made it onto The [David] Letterman Show and about your performing career.

Well, I got a call from the Letterman Show—I don't even remember who it was—saying they liked my Lampoon work and they wanted me to get involved with writing for the show. Which I did. And then we cooked up this crazy routine where I played an imposter who... what would happen was Letterman would introduce a famous person, but somebody whose face you weren't likely to recognize. Like a bestselling author. And I would come out and [Letterman would] interview me as if I were that author, and we would be two or three questions into the interview and I would get to the point where I would have a total meltdown and breakdown on the stage and say, "Mr. Letterman, Mr. Letterman, I'm not really-- this certain person-- I just wanted to be on television... I'm sorry." [Laughter] And I would run up through the audience apologizing to everybody.

NEWGARDEN: I see here that you were claiming to be both Sally Field and Burt Reynolds [at the same time]. [Laughter]

Yeah, it was a wonderful routine.

KLINE: You did Don Henley, Donna Summer...

Yeah, I did Don Henley, Donna Summer... a lot of people don't remember this, but there was a Letterman morning show, before the evening show with David Letterman, and I did a whole bunch of the "imposters" for that show. The thing about [the morning show] is that it was live - it wasn't filmed, it wasn't taped, you were right there live, and if you made a mistake there wasn't any recourse. You just had to try and wiggle out of it, but I loved it. But being on live TV is a strange feeling.

KELLY: I've heard that there was a cartoon of your work created for Saturday Night Live, but it never aired. What can you tell us about that?

It happened when Bob Blechman was in contact with Saturday Night Live, and he was supposed to create some short animations for the show, at least as I remember it. I submitted some ideas, perhaps as scripts or storyboards, and we settled on one that featured a character called "Two-Headed Sam," who now appears in my book. Blechman worked with an outside source who took my story and turned it into an animated short, and did the same for the other cartoonists whom Blechman had asked to take part. They even told us that we could wait in the green room on the night my cartoon would be shown. Susan and I went over there with great anticipation, but the staff were totally perplexed and didn't have any idea who we were, or why these two unknown strangers would presume to think they were invited to the green room. Actually, I had been in a green room many times when I did my skits for the David Letterman show. That's all I remember. The piece was never shown. No one told me what happened to it, and I suspect, although I'm not sure of this, that none of the work of the other contributors was used either. What happened was in no way Bob Blechman's fault - we gentle cartoonists, hovering over our drawing boards, are no match for the crazy hyper world of television. Disclaimer: These are very old memories, and I hope I'm getting it reasonably right.

Mountain King was a video game published by CBS Electronics in 1983, and was available on various gaming platforms. Subitzky wrote some of the copy for the game's advertisements and starred as a middle-aged gamer in this commercial.

NEWGARDEN: Tell us a little bit about Mountain King. That's a part of your career that I'm not quite as up on.

Ok, I'm ashamed to say this... this is not something that I'm sure I want anyone to know about, but I had a day job. And my day job was in the advertising business. I was a copywriter. And again, I'm not being boastful, but I was actually very good in advertising. I had a real knack for it. And one of our clients wanted us to do a TV commercial for a video game. And we auditioned and auditioned, and we couldn't find anyone who seemed to fit the bill. It ended up that the director said, "Why don't you try it, Ed?" And so I tried it and he liked it, and so I ended up playing someone playing a silly video game called Mountain King. And I had a great time. I loved it.

NEWGARDEN: I did some research on Mountain King recently, and somebody online calls it "the scariest video game ever created." What was so scary about it?

Me, probably, in the commercial. [Laughter] I love to perform. Because of the Mountain King commercial, I actually have a [Screen Actors Guild] card. Although I shouldn't say that, because we're actually on strike... I'm sorry, the union people are coming after me right now. [Laughter]

NEWGARDEN: What was it about the 1970s that allowed a guy like you to become a model and a TV show star and a cartoonist and a writer, doing stuff that probably would not have flown in the 1960s... or perhaps again in the 1990s?

You know, I really wish I could answer that. I think you'd need a historian to tell you that...

NEWGARDEN: But you were there!

Yeah, I was there, but I never was really a part of the scene. I was always the shy person huddled over my drawing table or a keyboard at my computer. I never really got involved in all the stuff that was going on, so I have to not answer that question completely because, although I was there, I wasn't really there in a certain way.

NEWGARDEN: You were doing op-ed comics for the New York Times for a while. What was that like?

I did a few of them. The person who was in charge of that was Nicholas Blechman, son of Bob Blechman, the cartooning teacher that I had [at SVA]. So it was really easy. He called me up and gave me the topics and I sat down and did a few cartoons for them, and he liked them and he used them. I stopped doing things for them, and the only reason I can say that I did that is that when I was doing [the op-ed cartoons] I had a very demanding day job and it was getting harder and harder to squeeze this stuff into the evenings and weekends. So I kind of had to pick and choose a little bit what I did and didn't do. And made all the wrong choices, like we all do. [Laughter]

I have a question, is there anybody here tonight in the audience who has ever made a right choice in their lives? [Laughter]

KLINE: Can you talk about some memories about Harvey Kurtzman?

Oh, I worshipped the old Harvey Kurtzman MAD comic books. In the very early days of MAD magazine, Harvey Kurtzman wrote these hysterical parodies on the things that were going on - like the TV show of the time, but more than anything, the comics of the time. And there were illustrated by people who could pick up the style of the original cartoonists that were absolutely perfection. And I adored those. I read them to this day. I have old, yellowing page books of them. But I'd say that Harvey Kurtzman had a big influence on me. In fact, should I tell the story about how I met him?

KLINE: I think you should.

Okay, I was about 14 years old and at the height of my love for Harvey Kurtzman. I worshipped him. It was like God himself had come down to Earth. And what happens? It turned out that he lived across the street from a friend of mine, and the friend arraigned a meeting for me and Harvey. And it just so happens that when I went over to meet Harvey, trembling, another artist was over that day, and that artist was Bill Elder. And to me, not only Harvey Kurtzman, but Harvey Kurtzman and Bill Elder, was absolutely overwhelming. I didn't think I would survive it! [Laughter] My heart must have been beating so quick... they were just the finest to me. And did they influence my stuff? I think they probably did. I don't think I could have helped but have it influence my stuff, because I really adored it. I think that when you really love something it get its way into you, it influences you, whether you want it to or not.

My drawing style for comics has been compared with Bob Blechman, and a lot of people have even gotten angry with me, thinking that I was ripping off his style. But the fact is, I had been in his class and he helped me develop that style. [Laughter] The best thing that ever happened to me, cartoon-wise, was at that School of Visual Arts class. Because I was floundering around in the class, and the two instructors called me in at the end of one of the class sessions and said, "We want you try a certain kind of pen." And I said okay, not knowing about it, and it was called a Rapidograph. And it's not a drawing pen, really. It's a pen that architects use, basically. Or people who want really straight lines. I don't know of any other cartoonist who really uses it, but I tried it and my style just fell into place. It was a great gift. A great gift.

NEWGARDEN: And you're still using it 'til this day?

'Til this day. I still clog them up. [Laughter] I can't unclog them. I have to go out and spend more money on a new one every time I get an assignment, but that's the best part.

NEWGARDEN: Have you ever thought about teaching?

Not really. It's just a question of time. I like to teach, but I have a character flaw which would make teaching hard for me. I find it very difficult discussing [students'] work if I don't like what they've done. It hurts me. It hurts me more than it hurts them, probably. So I wouldn't be a good teacher because you have to be honest. You can't reinforce bad work and make them feel that it's okay. I just don't have the teacher's personality, I don't think.

***

INTERMISSION: A few audience questions

AUDIENCE: What was your earliest memory of wanting to draw a comic, and what you saw that made you want to do them?

The earliest memory that I have is that my father was a glazer, he put in glass and stuff like that, and he had a store that he operated out of. And they had big panes of glass that they kept in stock. And between each of the big panes of glass they had a big piece of paper, and I would pull the paper out and sit down at the desk there and start drawing. And I drew little comic strips. I can't image what they looked like. I would love to see them.

AUDIENCE: What was the first comic that you saw that you remember seeing?

I guess when I was really young—I must have been around 5 or 6 years old—I loved a comic called Walt Disney's Comics and Stories. I waited for it to come out each month. I went through all the traditional phases as a comic book lover. There was the Walt Disney strips, and of course I got into all the superheroes. As I got into my teenage and college years I particularly had a great affection for a series of Marvel comics that most people don't remember. They're called the "monster age," or monster books, and they're all about these giant creatures who came down to Earth to destroy us or enslave us or something. And they used that same theme again and again and again. [Laughter] And I loved them. I had a little collection of them for a while.

I still love comics, but life goes on and I get older, and I probably don't pay as much attention to the field today as I wish I did. I've always adored comics.

AUDIENCE: I worked with you at the advertising company... please tell people about the computer program that you wrote that made up nonsense words.

Oh...I had a hobby... [Laughter] When I was bored, I used to write these little amateur programs for my Macintosh computer. I fell madly in love with computers. I'm not [talking about inventing] Microsoft Word here, I'm talking about little tiny things, but I loved to get together and give the computer its instructions and checking the results and if they don't work right, trying to fix them. And one of the little programs I did generated a bunch of silly little nonsense words and nonsense conversations and stuff like that. I don't do it anymore, but I remember my computer programming days with much, much fondness.

AUDIENCE: Did you have any contact with the other cartoonists at the Lampoon?

A few of them, yeah. A few of them I became kind of friendly with. I was kind of close friends with Sam Gross. He passed away not too long ago. I would go and have dinner with him from time to time. And he was a great person, a very nice guy. He's one of those people who has a very gruff exterior, but it's all an act. He loves to put it on. He likes to act like the major rough and tough New Yorker. He's a pussycat. Whenever a cartoonist would have a problem, the first person they would call was Sam Gross. He was really sweet and I knew Sam best of anybody, and I think I hung out with some of the other ones a little bit, but the main one was Sam Gross. An amazingly great cartoonist. Every time I look at a Sam Gross cartoon, I get jealous. I think, "Oh, how could he do that? How could he think of that?"

My other favorite cartoonist from the Lampoon, who I only met briefly, was [Charles] Rodrigues, His work was very strange, really bizarre, makes my work look almost normal. [Laughter] And I understand that he was a devout Catholic, and it's hard for me to get a dichotomy like that, because his work was so wonderfully weird, and on the other hand he had this religious aspect to him. If I'm right. If the memory is right.

AUDIENCE: How much editing and rewriting generally would go into your work?

Into my work? Into a Lampoon piece from the old days? Or even today with the way I work today? I have to be honest with you, I don't know, because the way I work... I don't know how typical the way I work is, but generally, things just pop out of me. I have a feeling that it's all built up inside of my head, and then I'm just transcribing it. I don't really play [with] or edit it. The [text] pieces more, and I would rewrite different drafts much more than with the comics. The comics usually came to me right away. For better or worse, they were there pretty quickly. But I know there are people who work very differently. There are people who will slowly and systematically piece something together instead of having it just whoosh out of them the way it does in my case. But both ways are fine. You can do excellent, great work either way. It doesn't really matter whatever way you do it. The important thing is to do it your way, whichever one works for you. If you're analytical and detail-oriented in what you do, great. And if you like to let it all come out and land on the page and mop it up afterwards, that's fine too.

***

NEWGARDEN: Were you ever edited by the Lampoon editors?

Never. This was unheard of in the publishing business. You would go there with a bunch of pieces and they would take them and you would see them in print. They didn't edit them, they didn't change them, they didn't ask you to change them or ask you any questions about them... and I found out later in life what an unusual experience that was. That was not typical at all for the publishing business.

SUSAN HEWITT [Subitzky's wife]: Tell them about the one time that you were edited.

Oh, yes, there was one occasion where I was really edited. I had handed in a piece to Brian McConnachie of the Lampoon staff and he liked the piece, but what happened was... in those days, it was before word processing, and this was a [text] piece, and because it was before word processing, if you had a last minute thought you would take a pencil and show it on the page. You might cross out a paragraph, you might cut a few things here or there. And so Brian came to me and said, "Ed, we want to make one little change to your piece..."

And I said, "Whaaaa....?" [Laughter]

And what he wanted to do was put back a part that I had crossed out. [Laughter] So that was the only time that I was edited at the Lampoon.

A small sample from 1974's Official National Lampoon Stereo Test and Demonstration Record, which Subitzky conceived, wrote, and performed in alongside John Belushi, Chevy Chase and others.

KELLY: One of the Lampoon projects you worked on was the Stereo Test and Demonstration Record [1974]. You worked with John Belushi and Chevy Chase on that, before they became cast members of Saturday Night Live and, later, movie stars. Can you share some memories of that?

For those who may be unfamiliar with the Stereo Test and Demonstration Record, it was intended to be used as a premium related to all the stereo advertising that was helping to keep the Lampoon afloat at the time, although I believe it was also sold on its own. Yes, John Belushi and Chevy Chase were both major voices on the record, and yes, I was there too and actually directed them! They weren't world-famous then, of course, and I'm assuming that I just thought, who are these super-talented guys making my record album sound so good? What I can say about both of them is that each combined two traits, being incredibly funny and superbly professional. I remember, perhaps wrongly, that Chevy was quieter than John, and that John seemed to love the parts of the album that called for a lot of screeching and screaming. Please forgive me for saying it once again: these are very old memories, and the lens of time may have much distorted them.

There is a story I can report about John Belushi. On the night of the Animal House premiere, I was standing with a bunch of other people on a sort of balcony when, underneath us in a roadway, John Belushi's limo came up, parked, and John got out got out to gushing admiration, looked up, noticed me, and gave me a loud, "Hey Ed! How are you?" or words to that effect. Oh boy did my street cred jump! Suddenly I wasn't just another schlub standing around surrounded by people who paid no attention to me, but I was quite the Mr. VIP, and I thought I felt something from the crowd that seemed to acknowledge that. Now, it may have been that John Belushi was just doing the natural thing of saying "hi" to a person he had worked with, but I've always suspected that he did it as some kind of favor to me. A less shy person than I would have parlayed that one moment into meeting lots and lots of girls, at least in my fantasy. But all I remember is shouting, "Hi John!" [and] slinking back into the crowd, and then my red-carpet moment was over. Lucky me, poor me, I guess.

NEWGARDEN: I have a question about your day job [as an advertising copywriter]. What did they make of you there?

Oh, they thought I was a really strange person, but again, you can't say that you're good in advertising and be boastful at the same time. It's just not possible, because advertising is... advertising. But I was really, really exceptionally good at it, so they put up with me. [Laughter] One of the ways they put up with me was... I was a totally an evening person and I could not get up in the morning, and I used to always go in an hour, two hours late every day, and they hated that but I was bringing in big money for the firm. And that overrode everything of course, and they kept me.

KLINE: Did the advertising job in any way lubricate what you were doing in the Lampoon?

That's a very excellent question, but the fact is I tried to keep them as separated as possible. I made a very conscious effort not to let one have anything to do with the other. Advertising was for earning money, to pay the rent.

Cartooning was for the joy of life.