I first met Owen Kline over a decade ago; a teenage comics fan and aspiring cartoonist (not unlike the lead character in his film) at a Gary Panter event in downtown Brooklyn’s late great comic book store, Rocketship. Jump cut to a few years later and Owen was an able-bodied hand on the S.S. How To Read Nancy, painstakingly transcribing the last known interview with cartoonist Harry Haenigsen, then in his 90s, from an already disintegrating VHS tape. When it finally came down to “comic books or movies?” Owen cast his lot wisely and his first feature, Funny Pages, is an over-the-shoulder glance at the road not taken, capturing something specific and genuine of that Rocketship milieu. It also captures the sort of single-mindedness, self-absorption and hunger required to transition from comics consumer to comics maker, as well as something about the kind of moths who are attracted to that particular flame.

Funny Pages tells the story of Robert Bleichner (Daniel Zolghadri), an upper middle class kid from New Jersey and wanna-be comic book artist who dives headfirst into the adult end of the pool, ready or not. After the death of his beloved high school art teacher (which he may or may not be responsible for) Robert scores a day-job as a factotum in a public defender’s office, an after-hours job in a comic book store, and a mattress in the sweatiest apartment share in Trenton, while relentlessly pursuing his muse. Fate intervenes when Wallace (Matthew Maher), a troubled ex-con / ex-mental patient / ex-assistant comic book colorist crosses his path. Robert befriends Wallace; desperate for any possible industry connection, while Wallace is equally desperate to have Robert score his meds and harass his pharmacist. In the final act, the two make arrangements for a Christmas day inking lesson at Robert’s parents’ suburban home, unexpectedly joined by his high school crony Miles (Miles Emanuel). Dangerous comedy ensues.

Owen Kline began in the movie business as a child actor, best remembered for his leading role in The Squid and the Whale (2005). He launched his writing / directing career in 2014 on an iconoclastic note with a short pairing the late NYC talk show host Joe Franklin and a toddler named “Jazzy”. That short’s cast included Michael Townsend Wright, who triumphantly returns in Funny Pages as Barry; a plodding, toenail-picking, subterranean roomie. Both films share a kindred cartoonist’s vision; nightmarish, absurd, yet utterly matter of fact. (One might dare call it Plonsky.) And while there is plenty to laugh at in Funny Pages, some of the best moments offer an unexpected insight into the inherent tensions between the values and preoccupations of childhood and those of the so-called adult world.

Funny Pages was nominated for a Golden Camera award at Cannes. It was a New York Times Critic's Pick, and opened on August 26th at selected theaters around the country. You can be find streaming options for the film at the A24 website.

-Mark Newgarden

Written and directed by Owen Kline

Produced by Elara Pictures

Distributed by A24

MARK NEWGARDEN: When did you stop wanting to be a cartoonist?

OWEN KLINE: I never stopped drawing, but mostly I just do it for myself these days. I rarely draw comics anymore, though when this movie was broken down on the side of the road for a few years there, I would always calm myself by saying I could still finish the story as a long-form comic. When I was a really little kid, at 10 or 11, I mailed sample comic strips to King Features [Syndicate]. I’m still waiting for a reply.

For me, Funny Pages hits a lot the right notes. You not only capture the disturbing quality of certain individuals who are attached to comics, but the general futility of the whole endeavor. What do you think people want from comic books anyway? What does Robert want from them?

That’s a big question. I think Robert appreciates the human fingerprint inherent in cartooning more so than even the comics form, necessarily. He is very organically a humor cartoonist and a caricaturist, someone who looks at the bent world and figures out the way to bend it even more, or just magnify an aspect of someone to capture their essence. That’s a rare breed these days unfortunately. There just aren’t many slots for that kind of funny cartoonist, there isn’t a huge space for genuinely funny drawing styles in the culture anymore, as you well know. People like their cartooning a little more dressed up than that.

This comic book project took you six years to complete and went through several iterations, an unusual trajectory for an indie feature. Tell us a little bit about how it all started and what happened along the way.

Some things take a long time to steep. People chip away on their books and graphic novels for years but that’s hard with a film, but that was the only model this movie could afford. They always say: “Fast, good and cheap, you can only have two.” I wanted it to be good and knew it had to be cheap, so fast was out of the question. I wrote the earliest iterations about 10 years ago, and spent a few years trying to get anyone to even read it. Every door I knocked on, it was a lot of “we’ll get back to you!” Classic empty promise. I had designed it to be very cheap, but no one wants to give a kid in his 20s a film budget no matter whose ass you fell out of. All they saw was stink lines. Most people didn’t get it, understandably. But the Safdies were supportive of it, and found me the money and helped me tune up the script into something more. The humor and characters were there but I just chipped away at it for about a year with [the producers] Josh [Safdie] and Ronnie Bronstein, the third Safdie basically, and they helped me develop the story. Then we shot. I spent four years editing what we made in principal and just tossing and turning with it. And I ended up severing a two-hour film in half and simplifying it to a smaller chapter in this kid’s life, which it was always meant to be. Over those four years of editing, a lot of rewriting happened. I wrote a new 40-some pages and the reshoot was approved and I had 10 days to execute it. I couldn’t believe it was gonna get finished after so much uncertainty. And then, bang, the pandemic. So we had to wait some more. And more editing and rewriting happened. But it all gave me time to think. Six years is a good amount of time to spend on a feature, especially a first, I think. I worked all through that period and was very zen and patient about it all. Like birth, it’s a miracle when a movie makes it out of the vagina alive. It escapes!

With the (possible) exception of the lead and his immediate family, everyone in this movie is depicted as an out and out grotesque. What were you after?

I wasn’t actively thinking of this movie as a grotesque, although so much of my favorite art and comics are [what] I had in mind, like Crumb, Hogarth, our friend Drew Friedman, who like to portray extremes. I was just thinking about strong personalities and thinking in extremes. I guess I was just trying to make the world this kid romanticizes so real it’s surreal... or something like that. That is probably the idea that supported and validated the decisions you’re talking about. All the characters are falling apart a bit, so fake sweat and spit flies, and eyes drool, and all that [was] essential. Cartoonists know flaws are the funnest to draw. Our mutual pal Drew is obviously the king of wrinkles and liver spots. The world within the movie is a bit of a nightmare version of the adult world. It’s one without adults or decency. It’s heightened like a comic a bit, but I wouldn’t just make people look that sweaty for no good reason. It’s cause [they] live in a boiler room.

You tip your hat to many cartoonists and cartoon characters throughout the film. (I stopped counting after about two dozen in the first 10 minutes.) Can you cite the influential cartoonists who helped shape your worldview (and by extension this film’s)?

The ‘80s and ‘90s Fanta stuff was all still cover price when I was a teenager haunting the dusty back-issue bins, and those are what I immediately gravitated toward. Peter Bagge’s Hate and Clowes’ Eightball definitely informed the world. They were pointing to subcultural archetypes no one else was at the time and parodied their generation with the same relentlessness as Crumb or MAD. Chester Gould and his shooting gallery of inventive villains, especially the '60s work where it got darker. The Hernandez Brothers and their obsessive fixation on their characters and their interpersonal relationships. Drew Friedman’s comics with Josh Alan Friedman were formative. And of course the comical existential wretchings of Mark Newgarden. And Peanuts obviously, everyone is influenced by Peanuts though. I could go down this rabbit hole but those are some conscious influences in regards to the stuff that really stained me. Duplex Planet too, which has been adapted into comics by great Fantagraphics cartoonists. And lots of older comics too.

In Funny Pages we see numerous characters express themselves through their drawings. How did you cast the cartoonists whose artwork was featured in the film? Can you tell us who was used and why (and what was it like working with them)?

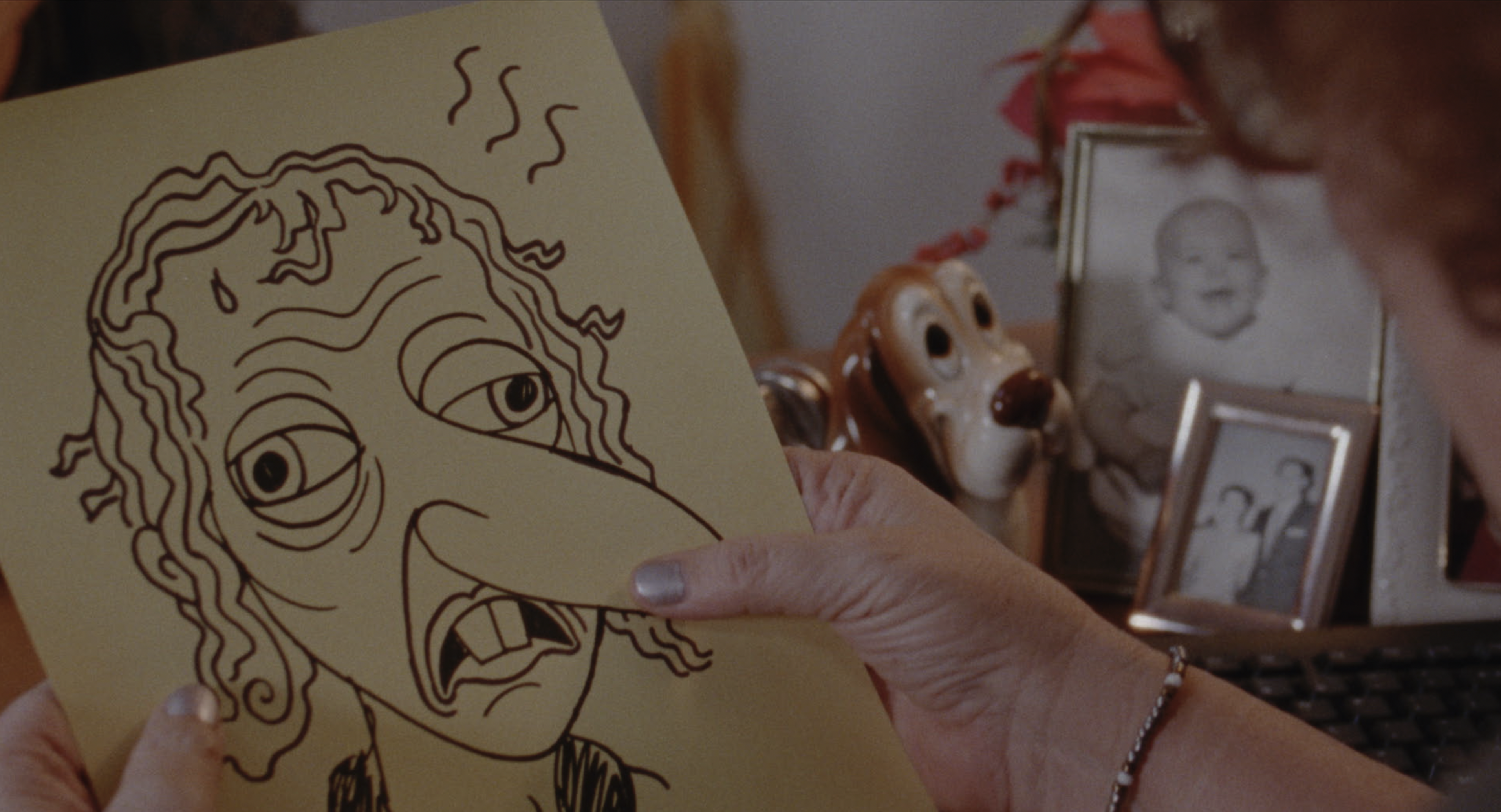

Originally I thought Robert’s character should be a mad crosshatcher and have an advanced but totally esoteric style of cartooning. And I got the great Rick Altergott to execute Robert’s portfolio. It ended up being the wrong decision. No high school student would be able to achieve a middle-aged master’s level. So I had Johnny Ryan create Robert’s art. I wrote a crass letter in Angry Youth Comix as a teenager, the same issue as Al Jaffee sang Johnny’s praises, and we had a rapport, and he knew the Safdies too. His style proved perfect for the character, whose work is unfiltered and unconscious and warped. And Rick Altergott’s work became the drawings of Robert’s late teacher Katano. That’s the kind of lavish work he maybe one day aspired to achieve. And our mutual friend Charlie Judkins drew Miles’ comics. He did them when we were in high school. That added a nice personal layer, plus they are a real teenager’s xeroxed minicomics and that maybe lends some authenticity. The way a character draws a face says a lot about how they see people. Their hand can reveal more than their mouth sometimes. Rick was a pleasure and so focused. And Johnny, of course you just let him do his thing. I gave him suggestions but I always preferred him to just go nuts. They both really got the script and its humor so it was very organic I think for them to have their angle on these characters and the characters’ various hands.

You come from a film family of multiple generations. How did the family business (as well your background as a child actor) prepare you for Funny Pages?

Creatively, but not business-wise. They are smart and have good taste, I think. I definitely… I analyze acting the way I do because of my parents and the discernment I was around as a kid, just seeing them watch movies and react to them. Business-wise… well, no decision about this film for me was really around business, period.

I was impressed with the dialogue, much of which felt improvised. Was it? And if not, can you describe your writing process?

Very little of it. Barry’s Joe Franklin and Gulliver’s Travels musings were really just Miles Emanuel and Michael Townsend Wright linking obsessive brains for a second. Then Robert comes into the room and it becomes scripted. Another heavily improvised scene was the first scene, with the teacher. Stephen Adly Guirgis who played Mr. Katano is a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright so I let him take liberties with Katano’s art musings there.

Can you tell us something about your choice of shots in Funny Pages? (I don’t think I’ve seen so many closeups of so many ugly mugs since the last time I watched The Passion of Joan of Arc. )

A lot of close-ups of hands and “dirty” over-the-shoulder shots of people drawing or looking at comics. Spaces we filmed in were usually full of fluorescent lights, so instead of pushing back against those constraints, we embraced them. Unsurprisingly, fluorescent light only looks good on celluloid. Both DPs, Sean [Price] Williams and Hunter Zimny, who work together a lot, are of the school of mind that you’re there to photograph the actors, and especially the actors’ faces, and they love close-ups. I think close-ups allow the micro-gestures on an actor’s face to tell the story. And they also just allow for a certain level of freedom in editing.

Our mutual friend, ragtime pianist Charlie Judkins, told me that Funny Pages reminded him of an Our Gang comedy. He has a point, there is something similar about the way the adult world is portrayed: unstable, sordid, and often terrifying. Did you feel this way about adults as a child? Do you think of yourself as an adult now? (I’m not sure I always do.)

Ha, that’s a great point and a very Charlie Judkins-y observation. I think Robert, the protagonist, has a little Spanky and a little Breezy Brisbane in him. It’s funny, as teenagers Charlie and I spent a lot of time with stunted or strange adults, whether they were older cartoonists at the indie-oriented comic shop Rocketship, a store where I met both you and Charlie for the first time, or film collectors or animation historians or 78 collectors, all the obsessive, great, crazy people we both know and share. Some are more sane than others.

That Trenton boiler room bunker is a character in itself. Disturbing yet plausible, I had flashbacks to some of my cartoonist friend’s most squalid digs back in the day. What was the impetus for that room and its inhabitants (and were you ever tempted to limit the story to that one locale)?

Yes I was tempted. I tried a few drafts like that, where it’s entirely about that one vacuum-sealed world and you never really understand what kind of world is on the outside of it, or where we really are, which read more like a play. I’ve twisted this story so many different ways over the years. But in the end I realized this kid wouldn’t realistically last too long down there, his excitement has a pretty fast expiration date. The basement was inspired by Joe Franklin’s infamous Broadway office. Joe was the first talk show host ever, out of New York. He created the format. And he had a bizarre local show and cluttered office. I met both Michael Townsend Wright there the first time, who played Barry and brought a lot of Joe to his depiction I think, as well as Cleveland Thomas Jr. who plays Steven, who Robert shares his bedroom apartment with. Or rather Steven shares with Robert. Cleveland answered the phones at Joe’s which would ring off the hook with Broadway Danny Rose showbiz types trying to get ahold of him. Cleveland also had to pick up the phone and catch avalanches of stuff falling. So that environment in general was very inspired by Joe’s office.

Why New Jersey?

Slobs over snobs. It’s America’s magnificent armpit. I just thought a kid growing up around the WFMU culture and with access to the Princeton Record Exchange—a store other stores pick from for resale—like the places he inhabits, the kid exists in a vacuum seal, doesn’t even take notice of the real world, or the modern world. Princeton and Trenton allowed for that, and a cultural contrast.

What sort of reaction has Funny Pages gotten from cartoonists? Comic book fans? Comic book retailers? Ex-mental patients?

All over the map. I’ve gotten crazy conspiratorial things. Cartoonists of all ages generally like it and relate to it, others don’t connect, which I get. You can’t make a movie work for everyone, just for yourself. But I got it out of my system and spent the time and care on it, and its time to move on now. It was an albatross that finally broke out of the cocoon.

What sort of reaction has Funny Pages gotten from people who have no frame of reference at all for any of it?

People who were, or are, in an art scene of any kind have been connecting with it even if they never picked up a comic in [their] life. The only thing that goes over their heads is that the character is a cartoonist, not an animator. What? Who calls a cartoonist an animator? Obviously an animator is a cartoonist, but not the other way around.

Over the years, there have been a number of films about cartoonists and comic books, but none that ever felt quite so… unsettling. What are your favorite movies about cartoonists (and why)? How does your film relate to them?

Crumb because it gets into both the influences and the formative… formative years of warping. Yeah. Ugly to say, but that’s the magic of that film, you really learn most of the experiences that are tattooed in his brain from the work, but it gives you this extra layer into Crumb. Obviously us two are burnt out about talking about Crumb though, it’s a given almost, so I’m trying to think of another… I also really like that one Jules Feiffer wrote that Alain Resnais made, I Want to Go Home. Grumpy old American cartoonist dealing with the French reaction to his work at a giant Parisian exhibit about the comic strip. One of the great movie endings too, a comic strip dress-up party concluding in a dark night of the soul.

What is your favorite comic book that almost nobody else knows about?

Well, in the modern day, I don’t think Steven by Doug Allen gets nearly enough love. Tiny, angry bitter drunk in a hat that tells everyone to eat some paste, is friends with other animals and a cactus who needs his “sauce” constantly and calls everyone babe. A very batty and delirious comic book laid out in strip format. I’d recommend it to anyone who likes Dada comic strips. It needs an omnibus - that old “Best Of” booklet [Kitchen Sink, 1998] isn’t enough. Same goes for Idiotland [Fantagraphics, 1993-94], his collaboration with the amazing, late Gary Leib. I mean, I really think in an ideal world Doug Allen would be doing that as a daily in a paper, with a topper too, that would be great.

What is your favorite movie that almost nobody else knows about?

The same as yours, Mark. It’s called Nothing Lasts Forever and is Tom Schiller’s greatest of Schillervisions. I won’t try to describe it because that would be impossible, but it is a masterwork oppressed by the studio and never given proper distribution.

What is your relationship with comic books today? Do you still read them?

Mostly I read newspaper comics. Ones published by the Nemo Classic Comics Library and Fantagraphics in the '80s. Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie volumes, V.T. Hamlin’s Alley Oop, Wash Tubbs…. Revisiting McCay’s Rarebit Fiend stories recently too…. Daily newspaper cartoonists are the most committed artists and really build intricate worlds since they essentially live at their drawing tables.

Will Robert Bleichner ever be published by Fantagraphics?

I could see him moving to Seattle and working in the warehouse. And maybe trying to slip his work to Gary Groth under the table, or put it on his car under a window wiper.

What can you tell us about your next project?

Like Funny Pages, it’s character-driven and a comedy. That’s all I know for certain about it until it’s shot and cut.

* * *

Owen Kline will be in conversation with Drew Friedman at NYC's Society of Illustrators for the launch of Friedman's new book, Maverix and Lunatix: Icons of Underground Comix. The event is November 17th, and will be followed by a signing.