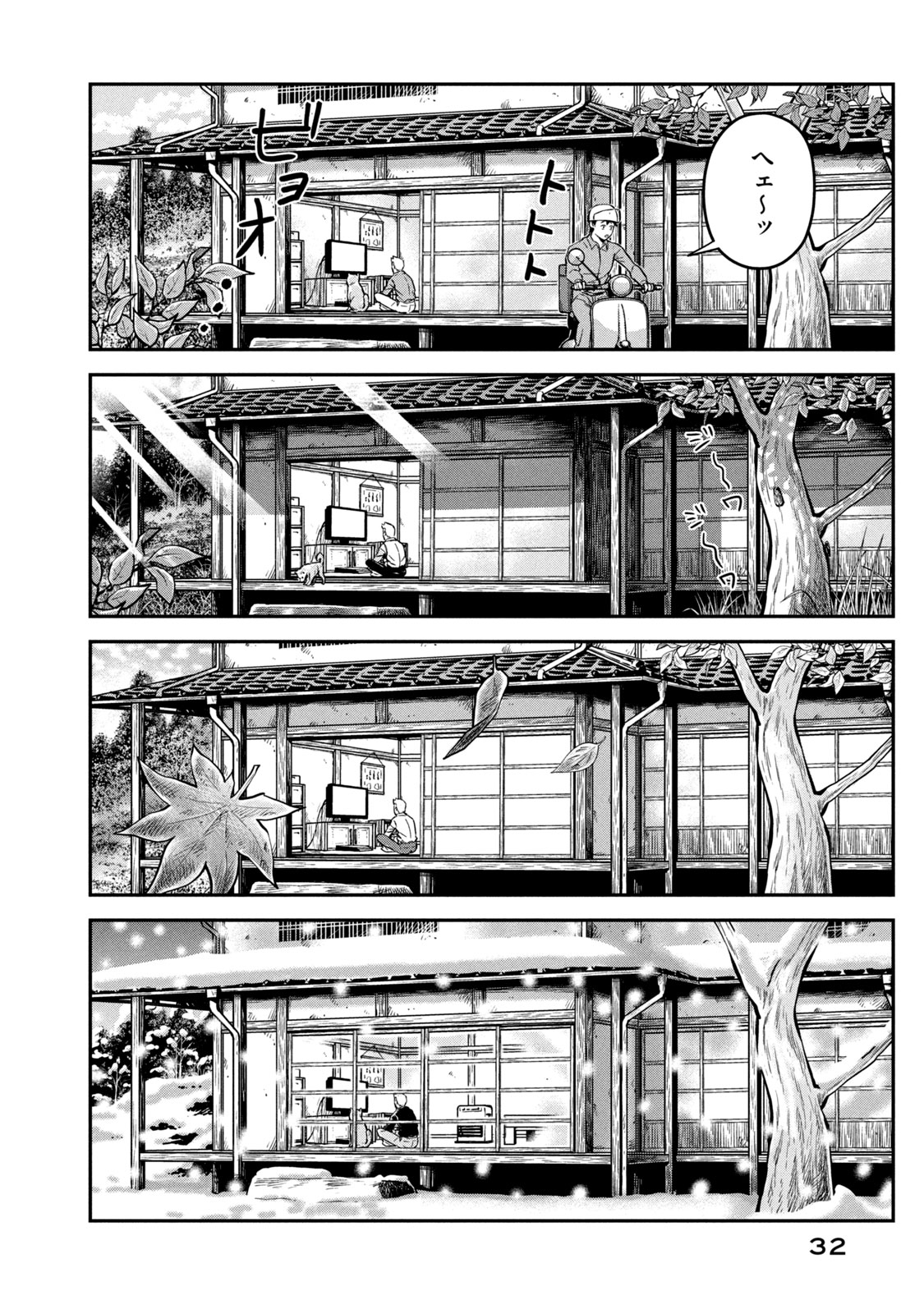

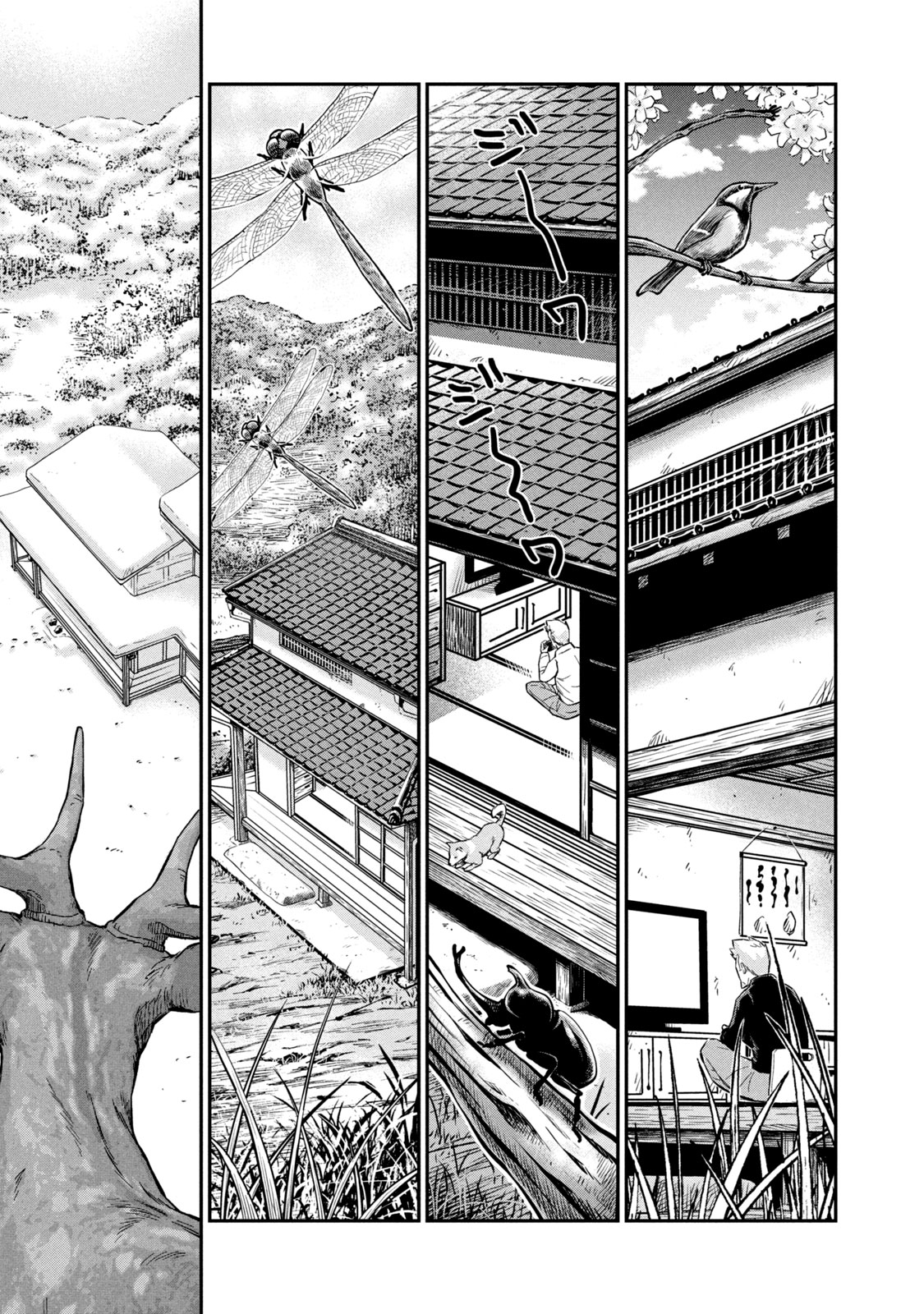

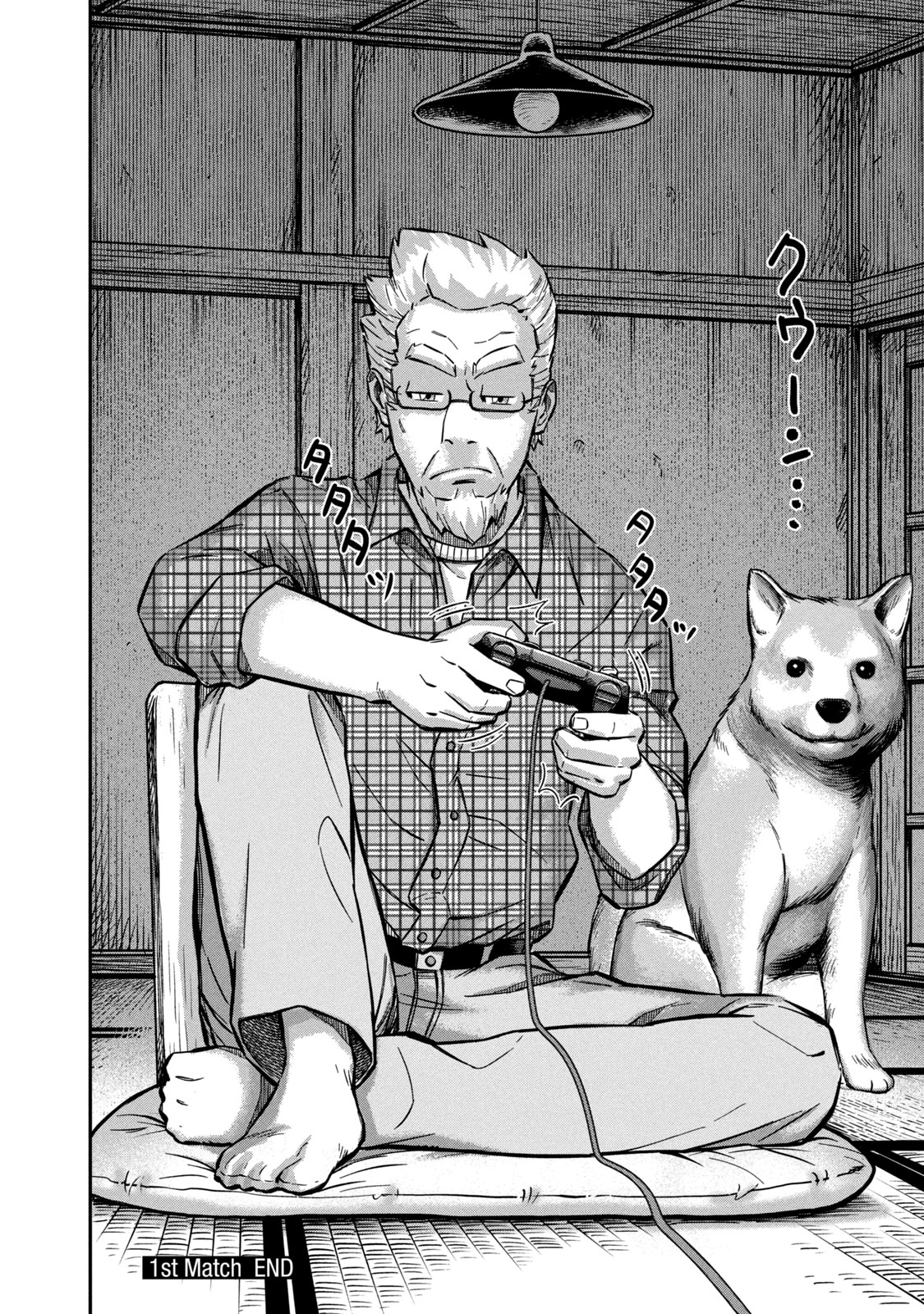

Juan Albarran is a Spanish creator who first broke into comics as an inker at DC. He worked in that vein for almost seven years with artists like Bruno Redondo and Daniel Sampere, as part of the Spanish creative scene. But after COVID, Albarran made a drastic change in his life and career, and now draws Matagi Gunner, a series for Japanese publisher Kodansha’s weekly seinen magazine Morning, in collaboration with writer Shōji Fujimoto. Aimed at adult male readers, Matagi Gunner is the story of an elderly rural hunter who proves unexpectedly skilled at video game first-person shooters, and soon becomes embroiled in the colorful world of e-gaming. The series' first collected volume was released in Japan last month.

We spoke with Albarran via Zoom this past September about the Spanish comics scene; how COVID struck American comics and changed his life; breaking into the Japanese manga market; working with Japanese editors and Kodansha; the differences between American and Japanese mainstream comics; the hectic, difficult life of being a mangaka; and plenty more.

-Ritesh Babu & Ari Bard

* * *

Part 1

RITESH BABU: So, you started out as an inker for American comics while living in Spain, and went over and worked as a mangaka in Japan. That’s what you’re doing now. Let’s go back to the start: what were the first comics that you read and made you say, “I love comics”?

JUAN ALBARRAN: You know, in my family, nobody was really a comic book fan, but somehow I remember that when I was a kid, like four or five years old, I remember a Superman anthology. It’s really difficult for me to say what it was, because here in Spain, a publisher would license those and just repackage them, and I don’t know if it was in order or if they chose a specific writer and put it together. But I remember Superman, and Spider-Man, and I do remember Sal Buscema, the Green Goblin comic that will haunt my nightmares forever, and some Spanish books too. Superlópez, which is a Spanish spoof of Superman. Very humorous but very good. It had a very cartoonish style but was very good. Also some French, European comics with Tintin aesthetics.

RITESH: Bandes dessinées, yea.

Exactly. Basically whatever was well known at the time. Somehow my parents would just buy it, and I would realize later that it was never good enough for me to just read or consume something. I had to try it. And so from reading those comics, I started copying them. So yeah, those are the first memories I have when it comes to comics.

RITESH: What about manga? When was the first time you really saw manga, and what was your first experience like?

Manga didn’t come to Spain until a little bit later. The first manga that came into my hands wasn’t even a manga. It was the Akira movie, which blew my mind. That was 1980something, and I was in my teens. I was not ready for that. I got really obsessed with Akira, and because of the success of the movie, the manga got published in Spain. That was the first manga that got into my hands, and it changed me forever.

RITESH: Ōtomo!

[Laughs] Yeah. Then the next thing was the Dragon Ball anime. Here in Spain, anime seemed to be, at first, the door that got opened for manga to come in. Anime would get shown on TV, and whatever show was really popular, some publisher would import and translate the manga, so Dragon Ball was probably a big influence for me and the first manga that I collected. Akira was a movie I watched and was really obsessed with, and I tried to find as many issues of the manga as I could, but it was published here in a really strange way. It wasn’t in the tankōbons [small collected books] or anything, it was in a really strange 30-page, big format. Dragon Ball was the first manga I collected.

RITESH: I don’t know if you follow football, but I remember Messi, Iniesta, Xavi, just that generation talking about how Captain Tsubasa was huge for them. It was massive and now Iniesta is in Japan, so anime as the first reach as opposed to manga makes sense.

Yeah, I actually live in Barcelona. I am from Barcelona, and I am a massive Barcelona [football] fan. Big fan of Messi, Iniesta, and everybody. Captain Tsubasa was like the second generation, so to speak, of shows that came into Spain. Again, it was not really the manga. The manga got published here, but it didn’t sell, and I don’t know why. It was the TV show, the animation. People got really obsessed with it, and we were not used to seeing such a dynamic, exaggerated representation of anything. It was like Dragon Ball. We’d seen fighting in stories before, but Dragon Ball took everything to a scale we’d never seen before. Of course we’d seen football, or soccer the way you call it in America, but then you get Captain Tsubasa and it’s like, “What the hell?” It’s like Dragon Ball people playing football. It was really different. So that was a big influence, but artistically, not so much for me. I was hooked. Every week they would show an episode, and I would stop whatever I was doing, I was in school at the time, and I would watch it, but I wasn’t really into the storytelling so much and the art style. I don’t know why, but it was not really a big influence for me. Of course I play sports. I played football for a few years, but it was not like Iniesta inspired me to play football.

ARI BARD: Right, right, so what, artistically, was what made you say, “Okay, I want to pursue this seriously. I want to create comics?”

I don’t think it was just one moment. I remember being really small, like four or five years old, and I always wanted to create something. I always had the instinct; it later became apparent to me when I got into other things like music and photography before coming back to comics eventually, which is what I think is my calling. I was drawing and, by chance, I got two 2nd or 3rd place prizes in some local drawing contests. One in school and one that was in my neighborhood, and it told me that I was doing well. So I was drawing comics, but I didn’t really think about doing it professionally. The first thoughts I had about doing it professionally was when I was 18 and I got into college and did my first year of law school. I hated it so much that I decided I just wanted to get out of it. I joined a school, kind of like the Kubert School, but not as good, don’t get the wrong idea. It was just a much smaller school, and at the time it was the only place where they would teach comics and how to make comics here. My parents were paying for my education at the time, and when I said I wanted to quit law school and make comics, that didn’t go over very well with them. They thought I was out of my mind. I ended up going into the military for a year to clear my mind. I came back and got a degree, sort of like a different kind of law degree that was only three years. That time was a time where I kind of forgot about comics for a while. I didn’t draw or read comics for about 10-12 years. That’s when I got into music.

Sometimes I wonder if I had kept drawing during that time, what my life would be like. I might be a much better artist now, but unfortunately we’ll never know. So I was into music, and I actually moved to America. I lived in America for about 10 years. Then something traumatic happened in my personal life, which was basically a divorce. It was a serious, traumatic situation for me, and it made me-- it sounds like I’m a manga character now, but it made me change my life. I went back and thought about who I was before I changed my life by going to America and all of those things, and I really missed creating and drawing comics. Just sitting down at the table by myself and drawing. So I started drawing again, and because it was such a difficult time for me, and I was a bit lost-- I was pursuing music for quite a few years, and it was my goal. Then it became clear for many reasons to me that it wasn’t what I wanted to do, and I needed something else to chase. I’ve always been the kind of person where it’s not good enough for me to just get up, go to the office, clock out, go back home, and do it all over again the next day. I need to chase some bigger goal. Music was that for all of the years I didn’t draw comics, but at 32 or 33, I made up my mind to go back to comics. I started drawing again and decided to go back to Spain, in Barcelona, and I enrolled in that school that my parents didn’t allow me to enroll in when I was 18. I was an adult and I made my money, so I decided I didn’t care what my parents said and enrolled in the school. So very late, at 32 or 33, I decided I was going to become a professional.

RITESH: Gotcha. And there is a long history of comics in Spain, right? Paco Roca is a huge name now, and there’s Editorial Bruguera. There’s a long tradition there as well. It’s not quite the Kuberts, but there is a sort of comics as an tradition. It’s not quite the French Ninth Art, but there is that thing.

Yeah, and I’m not quite sure why. Maybe it’s because this school, Joso School by the way, is here in Barcelona, but a lot of that activity and scholarships that you’re mentioning happened here in Barcelona. Many people, for some reason, from other parts of Spain came here to study in this school. There was a big community, the biggest comic book store in Spain is here, and it even won an Eisner a couple of years ago about being the best store in the world or something like that. So there’s a pretty big tradition here, but the thing is, there’s no industry in Spain. If somebody wants to make a living as a cartoonist or comic book artist, pretty much all of us have to go and work for the American market or a different market; and now, of course, apparently the Japanese market is also an option. There's a few people that actually do it here like Paco Roca. Paco Roca is one of those people that managed to publish between France and here in Spain and became a big artist. Some of his books have been adapted to animated movies, but there’s no really big money. Eventually, I think if you want to make a living at comics, there’s a big tradition of publishing and of artists, but if you’re Spanish, you usually have to go outside [of Spain] and look somewhere else.

RITESH: So when was the moment when you decided to work for the American market? How did that process go? When did you break in and how was that journey?

That was a little bit of a coincidence. You will see that there’s a bunch of moments like this in my life when I kind of plant seeds, somehow, and one of them grows without me knowing, and something happens that creates opportunities. I was studying in school, and when we were studying, I was so frustrated, and still am today, about my drawings. I do a drawing and I just don’t like it and try to find what’s wrong. Is it the drawing? Is it the inking? At some point I thought that what was screwing up my art was my inking. So I got pencils from professionals and inked them in order to practice so my inking would get better. I started to do that and went to the internet and started inking pages from other people. I realized myself, and got feedback from other people, saying, “Hey, you’re actually good at this,” and I started sending samples to agents here in Spain, posting online of course, and trying to network as much as I could.

It turns out, another inker, Jordi Tarragona, probably one of the best inkers here, saw my work online and was offered Nightwing in [DC's line-wide relaunch] New 52 back in 2013 and he couldn’t do it. Also the [penciller] was Juan José Ryp, who was very famous because he uses a lot of detail and takes a lot of time, and [Tarragona] couldn’t handle it at the time. He saw my work and sent me an email out of the blue saying, “I‘ve seen your work. I have this opportunity for DC. Do you want to try?” I was surprised. Again, I just posted work in some places until somebody saw it. I said yes, and back at the time, I had a day job. Basically, I was doing a little over half of a Nightwing issue while having a day job and working over the pencils of one of the artists that has a high amount of detail on each of their pages. It was a bit of a nightmare. It was so stressful, but I did a good enough job that it got published, and it gave me somewhere to work with.

Now I was not just an unknown person trying to break in. I had something to show, so I started to send those samples to everybody, meaning editors everywhere, especially Marvel and DC since smaller publishers typically don’t have the money and resources to pay inkers. Also agents here. There’s two or three big agents that network and have a roster of artists and pencillers that an inker can work with or team up with. Then, wherever the artist goes, the inker goes with them. Eventually another opportunity came up, but it was a year and a half. I thought it would be shorter than that. I was working my day job and doing samples. At that point I realized that my pencils were not where I wanted them to be. I did not think I was going to get a chance with my penciling, but my inking seemed to be working. So I went all in on inking. I basically stopped drawing except occasionally for fun. I knew my chance to get into the comic book business was going to be through inking.

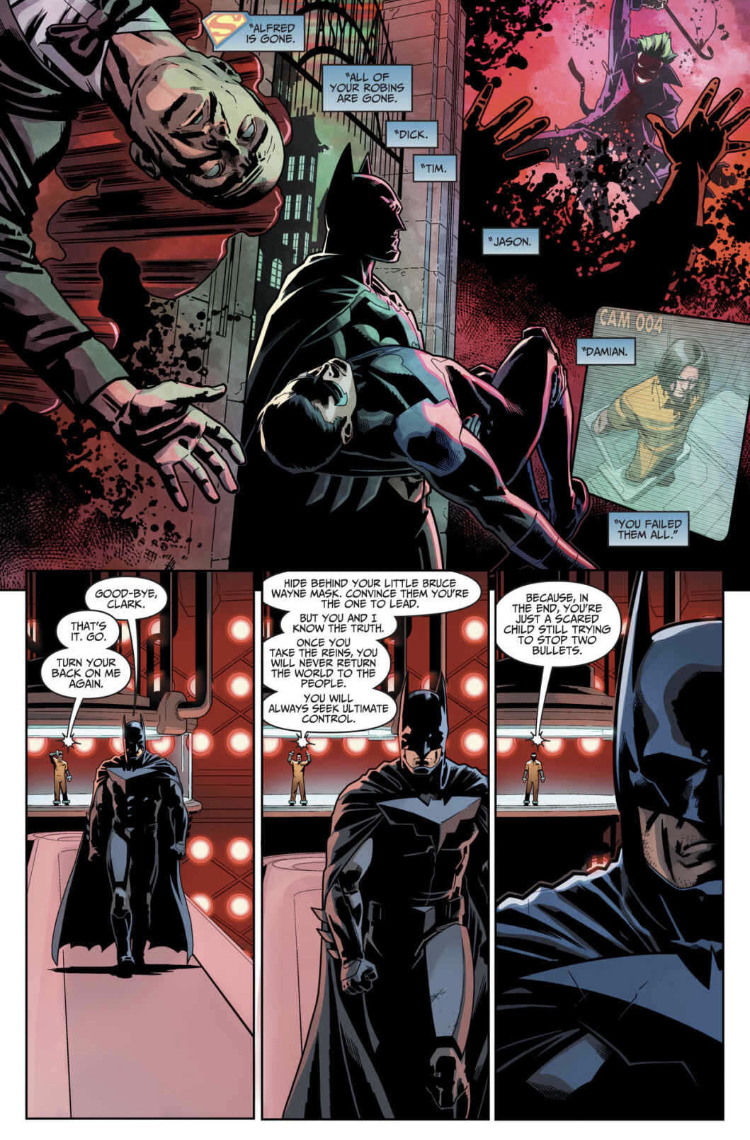

I did that, and after a year and a half of sending messages to everybody-- and I mean everybody in New York or LA that had a comic book company. Then, one of the editors at DC, Jim Chadwick, was editing Injustice at the time. He sent me an email saying that “Hey, we’re basically desperate. We’re running behind and need help with one issue. Would you help us?” I said, “Of course!” and basically did one issue, which was ten pages for digital. It was digital first and would come out at comiXology. Then they would put two chapters together to make an issue for print. I made one of those 10-pagers, and the artist, Bruno Redondo, who is now doing Nightwing, liked my inks and asked to team up. He was working with an agent that I’d spoken to before here in Spain. The agent wanted me to join the agency to package me with Bruno as a team. Chadwick said yes, so I started working as a regular inker for Injustice, and that lasted three or four years. That was probably, to this day, the longest run that I’ve had.

ARI: That’s really important because you took what you thought of as a weakness that you were working on for yourself, and it became what made you known and what got you hired. I don’t think people realize those sorts of things can happen.

It’s funny now that you mention it. I’ve never thought about that. I was so frustrated with myself. My comic book career brings a lot of frustration to my life. I don’t know why because it’s just me. Nobody’s doing anything to me, it’s just me not being happy with the work that I do. I realized that avoiding the problem is never going to help. If I don’t know how to draw hands, I know that I will never make a living as a professional if I don't fix that problem. I knew my inks were not good, or maybe the problem was my pencils, because now that I think about it, whenever I inked over professional pencillers, apparently my inks were good. So I guess my problem was my pencils, I just didn’t know it at the time. What I thought was a weakness, which it probably was at the time, everything was a weakness at the time probably, ended up being my ticket into the comic book business.

RITESH: Eventually, you went from the American industry to the manga industry. Can you talk about that transition? How was that for you?

That’s thanks to COVID, basically. It’s a big gap. I worked as an inker for seven years. Working as an inker is a very comfortable life, in some ways, because the most difficult part of the process is already done for you when you get the work. For a writer or a penciller, dealing with the blank page is the most difficult part. You have to create something out of nothing. For me, when I got the page, I didn’t have to deal with that. It was very enjoyable work, but the problem with that was I was not in control of my career. Whenever DC, Marvel, or other publishers don’t hire inkers, they hire pencillers or artists. Those are the ones that sell the books, and rightfully so because of what I said. They do the most difficult part. Whenever the pencillers I was working with found a job, I would go with them hopefully, but you’re always fearful of an editor offering a better inker. Or, what can and did end up happening, was that the penciller, especially now with digital, may decide to ink themselves, for many reasons. They may want total control over what the pages look like in the end; they may want money, which is totally legitimate, or the publisher can decide they want to save costs or maybe they don’t like the look of a certain inker. At the time I was working with two pencillers: Bruno Redondo, who I worked with for six years, and Daniel Sampere, who is also an amazing penciller.

RITESH: He’s terrific, yeah.

I did the Justice League Dark, Injustice, Justice League, and we did Suicide Squad for a little bit. That was when the pandemic happened in April 2020. That’s the time where basically everything stopped. The comic book shops stopped and Marvel, Valiant and other publishers said pencils down. DC was the only publisher still marching on. They were continuing to make stories so that when everything went back to normal, they’d have comics to sell, but then Diamond closed. That, to me, was the thing that sealed the deal. Now it didn’t matter how many comics were being made because they weren’t being delivered to anybody. I don’t know, of course, how much money DC or Warner Brothers have, but I think at some point they decided they couldn’t afford to keep making comics when nothing was happening and no money was coming in. At the time, it looked like that was going to last for a while, which it eventually did. I think that DC decided-- and this is completely my conjecture, I did not receive any official communication from DC or anything just to be clear. I think that DC at some point decided to cut expenses and make less comics, which I know did happen for a while. They didn’t stop completely, but only the major comics, the Batman comics, were coming out. Basically, they offered, from what I know, Daniel Sampere to ink himself. I was not working with Bruno Redondo at the time, as he had already decided to ink himself a year before.

So we were all in lockdown in April 2020, and I was out of a job. I was really scared. Everything stopped except for the bills that came in the mail. I was like, “Okay, what do I do now?” Then I remembered something. Even though I’ve worked more years, the majority of my career, in American comics, I’d always considered myself more of a manga guy. As a reader, I enjoy manga, but I always thought it would be impossible to work in Japan. I don’t speak Japanese. I don't live in Japan. I know a little bit about how they work, and it’s all about the face-to-face interactions. You work with an editor almost as if they were another creator of the story. They’re never going to go for somebody that doesn’t speak their language. So I thought it was impossible and I never even considered it. But I was talking about the lack of control that I had when I was an inker, and I got really tired of that. I needed to start thinking about making the transition from inking to pencils.

I started to draw some samples of American comics. I would just look for scripts and have the samples ready just in case, nothing major, but then [COVID] happened When it happened, I had a bunch of sample pages for American comics, but the whole American market was closed down. I sent new pages, but nobody was even replying to emails. Everybody is usually pretty nice and would reply saying, “I don't have anything for you, but this looks nice. Come back to me in a few weeks or months.” Nobody was even replying. I remembered a tweet that I saw from a famous mangaka, who retweeted in early 2019, that was like “Hey, I’m looking for an assistant. And here’s the conditions of the job.” It had a link that took me to a website that was a message board where people could post as assistants looking for jobs or mangaka looking for assistants. A seed planted in my brain and I decided to bookmark this page. I lost my job and was tired of not being in control of my own career. It was time to stop being an inker now and I stopped asking publishers to give me work as an inker. This was my opportunity to go and try something different - to draw comics instead of just ink comics. But the American market was dead, so what did I do? I decided to go to the only market that never stops making comics no matter what happens.

I went to the message board and posted a message saying, “Hey, crazy guy from Spain here! I worked inking comics for a few years, and I can draw, so if you want an assistant, let me know!” It took 20 minutes for someone to reply. They were working for mostly commercial projects. In Japan they use manga for a lot of things, not just stories for magazines, but also to market a product. She was doing a lot of manga like that and was like “Hey, I need to practice my English. Will you work with me? I also love Batman! I love DC Comics!” So yeah, that’s how that happened. It was a little bit of a chance, like Jordi Tarragona sending me a message, but it was also a conscious decision I made that I was not going to be an inker anymore if I could avoid it because I knew there was no future in that profession. With digital, most artists have the time and the will to ink their own pencils in black, and that’s called inking these days.

RITESH: Out of curiosity, you mentioned you are a fan of bandes dessinées. Clearly the French industry is closer to Spain. Did you ever consider making a bande dessinée? It’s not a monthly, it’s just 60 pages, so there’s that.

I did and I didn’t. Thematically, French comics are not my favorite. I know that is a generalization and the French publishers make all kinds of comics. There’s a lot of history in comics, and you’d be unfair to say that’s the only thing they do because they also do manga and all kinds of work. But I was not known in the French market and I was not known in the Japanese market. I thought I basically had zero chance at each so if I were to choose, I’d choose manga because as a reader, I prefer manga. Also, the way Japan approaches comics and what Japanese manga meant for me as a kid growing up gave me more motivation to be part of that world.

RITESH: So now, when you think of manga, what are your favorite manga? What comes to mind for you and connects with you?

My taste has changed a lot over the years. I would like to think that the older I get, the more adult-oriented manga I enjoy, and I am not talking about [sexual content]. One thing I really like about manga is that-- I feel like American mainstream comics are, I don’t want to say for kids, but the kinds of stories you tell with superheroes are very limited to the action-adventure realm. Manga, Japanese comics, have the opportunity to be so much more diverse and they give the opportunity to people like Taiyō Matsumoto to be superstars.

RITESH: Yeah. You can make Ping Pong in manga in a way that you can’t in the mainstream American industry.

Exactly. You can make it, but I do not think it would be received or supported. Taiyō Matsumoto is one of my favorite mangakas ever. I also like another one, the total opposite almost, Mitsuru Adachi.

RITESH: Yes, Touch is a classic. Amazing sports mangaka.

Exactly. The way he tells stories with silent backgrounds, very understated stories. There’s a lot of panels with no text or very little text. He makes the reader work and say, “What is this guy thinking?” He doesn’t tell you everything right away. Also Akira. If you asked me what my favorite comic of all time is, I would say Akira, because it has everything. Now that I am working on a weekly schedule, it blows my mind what they did. The amount of detail and perfection they achieved on a weekly basis.... Personally, I really enjoy more adult-oriented mangaka like Jirō Taniguchi, Taiyō Matsumoto, Inio Asano, etc.

RITESH: What’s interesting to me is that you clearly reflect that. You could have gone to Weekly Shōnen Jump or Weekly Shōnen Sunday or Weekly Shōnen Magazine but instead you are at Morning, which is a seinen magazine.

Exactly, but I have to be honest: I tried everything. Even the type of manga I’m drawing now, if you look at the art style and the kind of stories we do, there’s a big component of shōnen, even though it’s a seinen magazine. There’s a big part of it, the videogame part of it, but we’ll talk about that later, that is nothing like Taiyō Matsumoto. Some of the pages I did to show my work to Japanese publishers were nothing like that at all. But then they take you and give you a chance to try to do what they want with this story and I do my best with what they give me.

Part 2

JUAN: Inio Asano is another guy I really enjoy.

ARI: I love Inio Asano. His work is really simple and human, it’s a lot of conversational pieces, but the way he renders everything is wild. His process is unlike anything else. He’s done interviews wherein he talks about how he’s used Unreal Engine, the video game software, to render backgrounds and stuff and how he does it from photos that he takes, it’s crazy.

RITESH: And he’s in Shogakukan’s Weekly Big Comic Spirits, yeah? Him, Naoki Urasawa, Yūgo Kobayashi, all of them are in that magazine and they do amazing work.

The advantages they have, Urasawa also, is that they are big stars now. So if they go “Hey I’m only going to make four chapters and now I’m going to take a break for a month!”, Spirits is gonna go “Okay, you do whatever you want!” [Laughs] I don’t have that luxury, I’m just a newcomer. But yeah, in general you asked me about this and I realize - to me manga gives you the opportunity to make stories and reach stories that I relate to as a human being. And by that I mean, people like me. Like, of course, they live in Japan, but they’re people like me. When I read superheroes, I read a Thor or Superman comic, it all seems to foreign to me. Like, these days if you asked me about my favorite superhero, I’d say y’know, Daredevil, Hawkeye, guys that are just human and normal and not so close to all that big cosmic action stuff.

And manga to me gives you a lot more of that, that human stuff.

RITESH: There’s also the fact that a lot of those superhero characters were created for a different period and a different audience a past century ago. And while there’s a lot of stuff in manga that is the older stuff continuing on, like say, Kamen Rider, the central focus is always on making new things, new series, and they become popular in their own right.

Yeah, you look at Batman for instance and he’s like 80 years old or something like that at this point. You wonder how many new takes or new things you can tell with one character, which I suppose can also be said about, I dunno, One Piece or those kinds of long stories, but like you said, every few weeks or a few months, you get a whole bunch of new series that are not based on anything. They’re not part of any universe. They’re just new. The work that I’m doing now is completely new. So I had to sit down with the editors and go “Okay, we’re going to create the look of this manga!” We don’t get to do that in American comics if you work for the Big Two.

RITESH: Yeah. There’s the pre-set expectation that Gotham has to look a certain way or Metropolis has to look a certain way or a costume has to be a certain way.

Exactly! That to me is very appealing, the fact that I have-- and of course it’s not just all up to me, it’s also the Japanese editors, who are very strict and have a lot of control over what I do, but I still have a lot more input on the final look of the manga that I’m doing than I ever had on any comic that I did for DC.

RITESH: And looking at the manga industry now, you can see Jump trying some stuff. There’s the Weekly Shōnen Jump magazine, but there’s also Jump+ now, the digital service where they’re publishing series and creators that can work on a more slightly lenient schedule at times than the regular magazine weekly schedule. Do you see that as a positive step forward? You hear so much about mangakas' health and them having to have surgeries and the schedule being very intense and them being hospitalized.

Yeah, actually, going back to the story of the mangaka that I started working for? I worked for her for six months, and suddenly she tells me “I fell sick. I have to get a surgery,” and I didn’t get to work for her for months. And basically after that I haven’t worked for her since. I found a new batch of mangaka that I work for, like four or five. And like, yeah, no, I’ve seen that.

For myself, the easier way to describe it is as a weekly schedule but in reality, it’s not really. I publish, we publish, three chapters every four weeks. Which is not 100% weekly, but it gives you one week to-- not to rest, because we don’t rest, but it gives you a week to just take it a little bit easier, or if I have to do covers for the tankōbons or promotional illustrations. Like today, I was doing a promotional piece because we’re now about to release the first tankōbon, with a famous Japanese professional e-gamer. So we have to do all these things. I don’t know how the people that work weekly-- and they have to deliver one chapter every week without the week rest that I do, and I don’t know how to do it. On top of that, I only draw. There are people that draw and write the story, and I think those are the people that end up getting sick and having all kinds of trouble.

Of course I haven’t talked about this with anybody or any editors in Japan yet, but you look at Morning, and there’s a big emphasis on the team - the writer and the artist. And it’s something I think other magazines don’t have so much. And I don’t know, and I haven’t asked why they do it like that, but I don’t think it’s a coincidence. I think it has to do with giving more time to everybody to do their job and have a little bit of time with their family or some free time.

Personally, having gone from not drawing a professional comic book page (I just inked a lot, I didn’t draw)-- from not drawing a single one to drawing 16 or more a week, it’s been too much of a jump. I’m still suffering the consequences of it, and still adjusting. And I basically don’t have a life, I’m basically just always working. This is my break, really, this interview with you. So I think the people that have been drawing for longer than me for years, they are faster than me maybe, and they are more used to the workload that they have to handle. And now I’m getting better, but at first it was like “Okay, I haven’t done anything ever, and now I have to do all this, and I have a team of three assistants!” That's a lot of pressure that I have to manage. Now I’m a project manager in addition to drawing my own manga. So I’m sure the people that have grown up in that culture, the manga culture, that know what they’re getting into, for them it’s like “Okay! Well, yeah.” So if editors give a little bit more time, it’s great, but for me it’s been the opposite, going from inking 20 pages over five to six weeks, which was a very easy life, to drawing nonstop. Like, I don’t do anything else besides this.

RITESH: So being a freelancer in any way is already hard enough, but especially an international freelancer-- I’m curious, if you’re allowed to speak on it, going from the DC payments and American comics payments, how are the Japanese manga industry payments? How is that pay structure and how has that process been, particularly because you don’t speak or read Japanese? Freelancing involves a lot of paperwork, especially to pay you and get you approved, whether it be PayPal or however. So how has it all been for you, the chaos of that?

So first of all, my Japanese editors do not do chaos, they’re very organized. That helps a lot. Also one of my editors, I have two editors, the one that I mostly speak with, she speaks a little bit of Spanish, so that helps a lot. But most of our communication is through email and I do it in Japanese through Google Translate and things like that. So it takes a while for me to receive emails and know what they’re talking about - money and important things like that. [Laughs] And just, okay, now I have to deal with this and make sure I understand everything.

I just signed the contract for the first tankōbon of my manga Matagi Gunner, which clearly states this needs to be confidential, so I’m not allowed to talk about the money. But I can compare. As far as page rate, I make less drawing one page in manga than I made inking one page for DC. So you’d probably say “Oh, that’s awful!”, which if you think about it considering the time that I take, yes, that’s not good. But, here’s the deal:

I would ink about 20 pages in four to five weeks, so if you make [those] numbers, it’s still not very good pay, [and] I had to usually take two books when I could. In manga, we make about 60 pages a month, by sheer quantity. And the sheer accumulation of pages like that ends up being a good amount of money. Now, I have to pay my assistants, assistants come out of my pocket. So this I’m not sure about yet, because the first tankōbon is set to get released on October 22nd, but I think it will work in my favor if the tankōbons sell well.

Here’s the cool thing - whenever you’re working for American mainstream comics, usually there’s fill-ins and you go do two to three issues of something. [In Japan] everything that goes into that manga is mine. Like, I drew it, me and my assistants. And if anything happens with my series, if it gets adapted to anime, adapted to a live-action movie, if there’s merchandise done with it, I get paid. If I draw a Batman comic and they make a Batman movie, I don’t get anything from the movie. Now here, I get it, I get it from everything done with the work. So the potential is just so much more, and you can make so much more money than you can in the American scene. But again, only if the manga is successful. If not, you can live by it. But it’s not crazy money. You’re not like Eiichirō Oda, who’s done so many chapters of One Piece in tankōbons and movies and everything. He’s a millionaire. [Laughs]

RITESH: Or a Takehiko Inoue on Slam Dunk or Vagabond, just huge hits.

Right! And also, the first tankōbon of Matagi Gunner is Chapters 1 through 7 of the manga and tankōbon two will be 8 to 16; just today I’m finishing up Chapter 15, meaning tankōbons 1 and 2 will be out soon, they’ll come out really quickly. I think that to put together a body of work that creates an income that passively just keeps coming in-- I don’t have to do any more work for that, that money just keeps coming in. So it’s a lot easier to, in four to five years, have a few tankōbons out that are selling. And hopefully they get translated to more languages, and that creates more revenue for me. I get a cut of the translated volumes and just a cut out of everything, like it should be, I think.

Overall, I think if the manga you make does well, I think you end up making a lot more money in general. If not, maybe it’s better to work for American comics, just because you get a better page rate and a better stable life.

If you work for Image and your indie comic gets made into The Walking Dead, you’re Robert Kirkman and you’re loaded, right? But that’s a bit of an exception. In Japan, I think that happens a little bit more often.

RITESH: I’m interested because you’ve done all of this, working in American mainstream comics and now the Japanese mainstream comics system, so in terms of the actual craft process, how much has changed or been the same for you? I know you talked about how you very much use Clip Studio Paint and you have your set of brushes, did you still work with that in this? How do your manga industry peers and assistants work? How is the process and craft of it?

They don’t tell you a lot about how you need to do your job, so to speak. They just basically help you if you need it. Like, I remember when I started, the guys at Morning said “We have a guy here at Editorial that’s like a Clip Studio guru, so if you use it, just let us know. Any questions you may have or if you send us your file, he’ll advise you on how to organize your page better.” Things like that. So that was really useful. Also, they helped me with the recruitment of the assistants, because I don’t speak Japanese. So I just give ‘em a call and talk to them. But the process - first you gotta start with the fact that I worked as an assistant for two years, so I learnt a lot about how the Japanese mangaka work with assistants from them, and then I applied that exact system to the way I work with my assistants.

My process has changed a little bit. The goal is always to be faster, right? How can I eliminate steps and try to do everything faster? Basically I have to do a chapter in a week, most of the time. 20 pages. Which you would think “Oh, but the assistants help you,” but I still have to draw the storyboard of 20 pages, and I have to draw 20 pages worth of characters and SFX and everything, which is what I do, everything except the backgrounds in about three days. Which is insane. You basically get up and draw, then stop, go to bed, then get up, next day same thing. And you don’t even know what you’re drawing anymore by the end of the third day, right?

So the process in a nutshell - the editor sends me a Nemu/Name from the writer, Fujimoto Shōji-san. The Nemu/Name is basically the script but they don’t give you the script written like PANEL ONE - GUY JUMPS.

RITESH: Like storyboards.

RITESH: Covered thoroughly well in Bakuman by Takeshi Obata & Tsugumi Ōba.

Exactly! If you’ve read Bakuman, it’s the same process. So they send me that, it’s been approved by the editors already, and they send it to me in Japanese, with all the text and everything. And also the SFX, that was a big thing for us at the start. How are we going to do the SFX? They’re a big part of the look of Japanese manga. So we decided that the writer was going to do it. So I get the Nemu, but I get it in Clip Studio format all ready. It’s not a PDF. It’s just the whole thing already done. And it has a layer with the text, and a layer with the SFX, and then the storyboard. Aside from that, I get a word file with the text, only the text. Panel One - Here’s what the character is saying, in Japanese. So I take it, and put it in the translator, put it in a file, everything in English. Really broken English, of course, but good enough that I can understand what’s going on, right? So with that, I go through the script, I go through the Nemu, I read what happens in the story/chapter and I usually understand and don’t have to ask editors about this. Just the storytelling of the writer in the Nemu is so clear, because the writer Fujimoto-san actually drew manga for years before he did this. So he’s a mangaka, but he just doesn’t have the time to draw a weekly this time. He actually drew a story for nine tankōbons for a monthly magazine before [Shūden-chan, also for Morning, 2015-20]. So I get that, I understand the story, and at first, I would do my own Nemu. When they asked me to do my own Nemu, and I was like “What?! We already have a Nemu! We already have a storyboard! Let me just do it!” But they were like “No, no, no, very basic but do a Nemu. Part of the job is you have to adapt this in the way you want to tell the story.” And I was like “Okay!”, but it concerned me a lot because I have to now also do the Nemu of so many pages on top of this weekly, and then draw more stuff.

So my process at first was like “Okay, I’m going to draw some very quick sketches,” and sometimes they’ll match what the writer will do, like I’ll like what he did. Sometimes it’s just very basic what he did, and I’ll have to add or come up with a few things. And then I would send that to the editor, and the editor would approve or ask for any of the changes. When he would give it back to me, I’d then draw the pencils, because that’s the way they do it in American comics - they do the storyboards, then they do the pencils, then the inks, and then the colors. So yeah, I would spend like two or three days drawing the storyboard, then the pencil, and then the inks, and that just took me too long. It was like “I’m not going to make it if I do it like this, this is not going to work,” so eventually what I decided to do is from the storyboard I went straight to pencils, and the pencils only for the parts that I would do, meaning I only [draw] the characters, right? And there’s a big emphasis from the editors on facial expression and body language. So I would do like a quick sketch of the background or take a picture and put it in, that I cannot use later for the final version, because they’re really big on not using copyrighted material, so I cannot just take a picture from the internet and use it. But something that’s good enough for them to visualize, then I would just do those pencils of the story and send it to them, it takes me three days usually to draw the pencils-- and when I say pencils, I also mean the lettering. The speech balloons and everything, I decide them and I make them. We don’t have a letterer at [our] end. The text is already there, so I just have to place the balloons, and I do everything. When they approve it, I just ink the characters, and due to deadlines, I ink the characters before I send the work to the assistants. Sometimes, a lot of the times, we have to do it in parallel.

So how do I work with assistants? Well, I have one Spanish assistant, and two Japanese assistants. The Spanish assistant is more fluid, especially due to communication, as we speak the same language. With the two Japanese assistants, it’s a little bit easier to work with, I think. They’re quiet and shy, but they get the job, they send me a Thumbs Up emoji on Discord or something. And then they do it. Three days later, it’s all done. It’s all very maintenance free. What I do is I distribute the workload to everybody, and then I write the type of script that American writers write for their artists. Panel One - Building, night time, it should in [insert] perspective. Sometimes I even draw the perspective or a very basic shape, and I send that to them, with as much reference as I can. Like if I want, I dunno, a crane in a port, I just look for reference online, and I send that to them. And because the writer Fujimoto-san decided that the main antagonist of the book was gonna be Spanish and from Barcelona, actually--

RITESH: Oh my god.

ARI: [Laughs]

That was a surprise! That was not my idea! They didn’t tell me! They just sent me the Nemu and at the end of the chapter, there’s the big reveal, as she’s in Barcelona, with la Sagrada Família in the back. And Japanese assistants don’t know what Spain looks like, so I have to send them a lot of pictures for that. On the flipside, we have to draw a lot of rural Japan, and the main character is a guy that lives in the country. And I know absolutely nothing about rural Japan. So they are very helpful when it comes to drawing food, houses, things that look authentic, because the editors were really concerned about that. They were like “Okay, how are we going to get the Spanish guy to draw this? This is so Japanese. And he doesn’t even live here, so he can’t go out and take pictures.” So that was a big concern, but the Japanese assistants helped me.

And also, something I think is very cool is that the editors took two trips to the countryside of Japan and spent two to three days taking pictures and sending them to me.

RITESH: That’s lovely.

ARI: Wow, that’s so great.

That is so great! I’ve never had anyone do that. I’ve found the lengths and the support the Japanese editors will give is just incredible. So they went to the country two or three times, and the manga is set in the world of Matagi, and Matagi is hunters, traditional hunters. So they actually reached out to real Matagi, real traditional hunters, spent time with them, went on a field trip, went to their houses and they allowed them to take pictures of their houses, their clothes, their shotguns, their everything. And they sent me like 5 GB of pictures of everything they saw. And that was really surprising. They also sent me a big envelope full of promotional material, like tourist material, that they found in the area. Like flyers, with pictures and information about the area, the animals and everything, and they even went-- one of my editors went to a very famous Japanese shrine in Tokyo and they bought me an object that gives you good luck, like a charm.

RITESH: That’s incredibly sweet.

ARI: Yeah, that’s so nice.

They sent me this, and I was like “What is this?”, and they said “This is a charm for prosperity and good business, and we wish you luck for the beginning of the manga and this series.” It was very sweet. And of course, they’re really demanding, they ask for a lot of changes and everything, but they sent me this charm, so I think it’ll be alright. [Laughs]

So yeah, it’s just great to work with people that seem to care so much about the work you do and about you as a person. The culture is just different here, and it’s not just my editors - I just think in general, the way they deal with artists.

RITESH: I’m curious. I’ve gone through the first chapter of Matagi Gunner, and obviously it’s untranslated, but you can still see and get the storytelling there through it. And it’s very much a comic that seems to balance on one end the sort of slice of life stuff with this old man as a lead, and then there’s also the wild, wacky video game violence to it. So how has that been for you, going from DC superhero fare to this?

I don’t know, I don’t want to sound cocky here. Working with American comics trained me in action comics. And then the comics that I read, which are, again, like Taiyō Matsumoto, a bit more slice of life. So I know both worlds, and I do think I’m getting better and better in the latest chapters, you can tell. Drawing more is what makes an artist get better, right? But it’s funny because Morning is such a big magazine, and they have such a long history of making comics, they’re in their 40th anniversary now, and they told me “The action pieces you’re doing, the action manga you’re doing, we don’t have it here.” You look at the other manga they publish, and none of ‘em are really action.

RITESH: They do publish works like Inoue’s Vagabond, which has amazing action, but it’s also utterly unique and mostly on hiatus.

Yeah. The kind of action they’ve been giving me in the Nemus to do, it looks a lot like superhero comics in many ways. There’s a showdown that happens in a city a lot like New York City, and I’m like “Okay, this is a bit like, I dunno, Elektra and Daredevil fighting each other in Hell’s Kitchen.” I was able to take a bit of that sensibility and take it there. And I also enjoy the other part of the manga, again, because I relate a lot more to the characters that I see in that world, right? More so than the video game characters, which are fun because of the stakes of the players that are playing those games; the real story is not about who wins in those fights, whether it’s a samurai or a robot. The real story is about this old man, and that to me is the drama that’s interesting about the story. So the one Spanish assistant I have deals with all the video game stuff, and the other two Japanese assistants deal with the real world stuff. So in a way it is like two different worlds, and we do try to make it look like two different worlds. So yeah, when I get a chapter, one can be more actiony, while another is more quiet, so it’s kind of like working on two different comics at once.

RITESH: The superhero point is interesting because Japan also has its own rich history of superheroes, because you have Shōtarō Ishinomori and Super Sentai and Kamen Rider, or even Ultraman manga going all the way back to [Kazuo] Umezu and his horror work. But also there’s the new contemporary Kamen Rider and Ultraman manga that exist. So there is that tradition, even looping in Fujiko Fujio’s Perman, for example, is another iconic one. So have you ever gotten in touch with that stuff?

Oh yeah. I’m a huge, huge fan of Ultraman. Huge fan of Kamen Rider. I actually just read the Seven Seas omnibus that they released in English a month ago. When it comes to reading, I’m actually more of a fan of older manga, like classic action like Ishinomori or even the work of Gō Nagai. But again, I draw for 2022 Japanese readers, so there’s things that have to look different, right? But I’d say, if you look at some of the characters, and I don’t know if the editors noticed, there’s one character who looks a lot like Kamen Rider in some ways. There’s a secondary character that gets killed in a panel who looks like Ultraman, but I just changed a few things so we don’t get into trouble and all that. I’m a big fan of the Japanese superheroes - tokusatsu. Huge fan of tokusatsu, I actually enjoy it a lot more-- listen, I’ll watch through an Ultraman series before I watch any MCU series.

And I do have to be honest, I would like to think I sit down and design a look for the series and all that, but a lot of it has been growing naturally, because we don’t have the time to sit down and think and design things for the most part. When there’s a new character, usually I write the design of the character on the page. I don’t have the time to do a sketch before. So I found that the look, the design, they just grow naturally. So if a script suggests this chapter of an American city, I just go “Okay” and try to make it a bit more like an American action comic and do something different, because that’s not the kind of action that they do there.

ARI: Right, right. And given you are in Morning, which is a seinen magazine, which is for an older audience, that kind of sets you apart, because this is usually something more common in a shōnen magazine. Readers come in more so for the story of the old man and him dealing with his grief, and they find this action derived from your time in superhero comics and the influence of the older manga you’re into. That should likely be a draw and a boost for the book.

If that happens to be the case, I will be so happy. To be honest, the editors-- not now so much because we’re now in cruise control so to speak, but at first I spent probably three months sketching two characters day after day. I was working as an assistant and sent in 20 pages, over 100 designs of the characters, and that’s when the look of the manga was actually established. There was a lot of input from them. I actually tried a lot of things. I tried to make it more retro, I tried to make it a bit more crazy, and that’s when you realize “This is still a business.” Some of the thoughts that I got was, which was a nice thing to hear, “We believe in this series a lot and we want it to be a huge success if it’s possible. And we want it to be accessible to anybody, and hopefully get adapted to animation, movies,” things like that, which I don’t know if it will happen, fingers crossed it happens and I make a lot of money. [Laughs]

But yeah, they tried to keep the style as mainstream and as neutral as possible. And of course, I’m not Japanese, I’ve spent most of my life not drawing manga, I did a lot when I was a kid but not after that, so it’s going to come out looking different. My style, if you look at it, the girls look manga-esque, the guys look manga-esque a li’l bit, but there’s something different, and I don’t know what it is. And honestly, I wish my stuff looked like the kind of manga I loved, right? And it just doesn’t, but I think in the end that may be an advantage. And one thing that they did, and this is what I think-- one of the points that made me go “I want to work on this manga!” because they offered it to me right away, is they sent me an email saying “Hey we’re looking for an artist for this thing, are you interested?”

And the elevator sales pitch was “This is a story about an old man that is so good as a hunter that his skills transfer to the video game world and he becomes a huge guy in the gaming world, he’s great.” And I thought, here you have the Morning story about an old man, like you said, whose life is basically ended, and there’s a new beginning of something, even though he’s reluctant, and if you look at his face he’s always angry. And there’s a big group of people that are not the Morning readership, which is the gamers, and this is I think what Morning is counting on for the series. We get the usual Morning readership, and if the manga’s good, they keep reading it, but then we have this other element of the video game, which - there’s not a ton of manga, a few but not a ton, that make first-person shooters a key selling point.

The cover of the first tankōbon was revealed by Kodansha and it had FPS in big letters, and even the promotional piece I’m doing is in collaboration with a big gaming team in Japan, so they’re trying to reach that gaming audience also. So that’s when you realize “Ah, I’m just a part of a much bigger thing here. There’s a whole marketing team thinking about this manga.” It’s not just me trying to put in Kamen Rider references. I do all that I can to put my stamp on it, but also I’m in the biggest-- I think Kodansha’s like the biggest publisher in Japan? And one of the biggest in the world. And their goal is to make money, so one has to keep that in mind. So y’know, just trying to balance out the artistic side of it with the business side of it.

Part 3

RITESH: Alright, so, the one big question I want to pose is: from what I understand, one of the things you did when breaking in after having been an assistant is that you made your own one-shot - Play Ball, a baseball manga, which is very Japanese, and then you had a friend translate it and an assistant letter it in Japanese with all of the right grammar and everything. Now you’re working on Matagi Gunner and you’ve broken into manga proper with a serial as opposed to just a one-shot. When you look at your future now, while you’re building your career, do you have any sort of “bucket list” items? What do you want to do and create while you’re making manga from here on out? What are your dreams? Do you have any publishers or magazines you want to work for? Do you have any certain kinds of stories you want to do?

JUAN: Oof. That’s a big question. Well first of all, the manga-- have you read Play Ball? It’s only available on my Patreon.

RITESH & ARI: Yeah.

Okay, so you know it’s so different from what I am doing now.

ARI: Right.

RITESH: Yeah.

So you could think, and you probably would not be wrong, “This is the kind of manga he wants to make, but he’s making something else.” There’s a mix of everything. First of all, I don’t see myself-- I have a lot more experience drawing or inking or making comics visually and not writing, so the idea that I have to do this, [what] I am doing now, and also write the story: it just gives me nightmares. Right now, I don’t think I would be able to do it. If in the future, maybe working for a monthly magazine, maybe I can write.

But also, what I’ve realized is when I get the stories from Shōji Fujimoto—and I don’t know if it’s just him—but they just never fail to surprise me. I’m not saying what we’re doing is a masterpiece, but [the stories are] so creative as far as like, “Okay now you think the next chapter is going in this direction,” and it goes in a totally different direction and it introduces you to new characters like, “Whoa, this is a different part of the universe that I didn’t know existed.” It’s just the way he creates characters. The main antagonist of the story right now is a guy with the head of a pumpkin that’s dressed in a chef’s outfit, but he’s actually a cat. So you go, “That’s so stupid,” [laughs] but then you look at it and you go, “Oh, that’s so cool.” So, he has examples like that, and he sends me the basic concepts for all of the characters, most of the time, that appear in the manga. It blows my mind, and I realized that I don’t have that type of creativity - at least right now. I don’t know if in the future, that’s something you can train like a muscle. So I don’t know if I feel ready to try and make my own manga.

With Play Ball, I drew it really fast. I did about five pages everyday, and I did everything. I did backgrounds and didn’t hire assistants or anything, and I wrote the story, but it was, again, a nightmare. One thing that happened is-- I’ve touched a little bit on the frustrations that creating brings to my life, and writing-- I’ve written so many comics, and I’ve finished so few. Somewhere halfway through the process, I convince myself that I’m not any good and that it’s not worth finishing. Play Ball was one of the few times where I didn’t listen. It’s like the devil and the angel [on my shoulder]. The devil is saying, “You suck,” and the angel is saying, “I don’t think you should listen to him!” This was the first time that I went to the devil and flicked him off my shoulder. I forgot about it and finished it even though I thought it sucked. Then I sent it to Japan and editors started responding saying, “Oh, this is great!” I’m so stupid. I am telling myself I’m no good when maybe I can tell stories. This is just a long, roundabout way to say that this whole process has been about self-discovery of what I am able to do.

I said yes to this job thinking that it was impossible for me to do a chapter in a week, and six months later I’m doing a chapter in a week. You know, I’m doing things that I didn’t think were possible because very few people or anybody outside of Japan have done it before. Right now, mentally, I am trying my best to make the series I am working on a success, and my goal long-term is to stay in Japan because I see so many more advantages to staying in Japan creatively and financially. Also the fact that I’m the different guy in Japan, that’s clearly the advantage for me. I’m sure some other people will come, and I’m not the only one right now - there’s another Spanish guy drawing Tezuka characters in a monthly magazine. I’m not the only guy, but I realize I’m a bit of an exception. At some point it won’t be an exception anymore, but while that lasts, that’s an advantage that I have. Obviously Japanese readers, when they find out that I’m Spanish, they’re like, “Oh, this is different, cool.” In the first tankōbon, they asked me to write a two-page short story about me introducing myself because they want people to know that I'm actually from a different place, different background, and that it’s not a coincidence that they used Spain in the manga. There’s so many advantages for me that I want to continue there. If Matagi Gunner was a success on the level of One Piece and I get to one thousand chapters, you will not hear me complain, [laughs] however, what I want to do is what the guy from Chainsaw Man is doing--

RITESH: Tatsuki Fujimoto.

Right, what [Fujimoto]’s doing lately is he's doing [a continuing series], and then he’s doing one-shots. I saw that and said, “Okay, that’s what I want to do,” because creatively right now, I’m following the story of somebody else. Sometimes I think, “Oh, it would be so cool to explore this other part of these characters or this story.” The other day I got an idea that would be very good for a one-shot, like a 40-page manga or something. Of course right now, I don’t have the time to do it, but I think that if I can get something that I enjoy doing like this with great people-- my editors are a dream to work with, I can make this continue for a long time and make it financially viable after so many years of barely scraping by with inking and the instability of the American comic book business. If I can finally establish myself as a well-known artist that has worked on series for many years, and every now and then I can just do my own creative little things here and there, I would be happy. Of course, I would say [that] if I knew I was able to write and draw my own story for a manga magazine and do whatever I wanted because I’m a big star, like Inio Asano does, for instance-- he just takes breaks whenever and writes the story he wants, that would be perfect. That would be a long-term goal that I’m not sure will ever be possible.

RITESH: Yeah, definitely, but at the same time, I am fascinated by how much you have done that has seemed impossible before you did it.

ARI: Right.

A lot of people asked me, “How did you find a way to send them your manga?” It’s there on their websites. Just go on their websites, they have a link. Send your work here. Why are you not doing that? Why is nobody doing that? It blows my mind. Manga [in western availability] has been going on for 40 years. The internet hasn’t been around for 40 years, but in the last 10 they have had that link there to send work. They have a monthly award, which is something that happened - I managed to find a way to get Play Ball to one of the editors at Morning. He liked it so much that he submitted it to the newcomers’ award they have every month. They told me that I was too old for the newcomer award, which was a different story, but I think that Play Ball was seen by all the editors - that’s how they decided the winner. I’m pretty sure that played a role in the fact that later on, just three or four months later, they sent me an email offering [Matagi Gunner]. Maybe I was too old for their newcomer award, but maybe they thought they could work with me. “He hired somebody, he paid somebody to translate, he paid an assistant to letter everything to make sure it was in place, [he] researched everything in Japanese.” Even if it was out of desperation, which it was, maybe that’s what they needed to see from someone outside of Japan. “He went through all of these hurdles, we’re going to give him a chance.”

RITESH: I’m fascinated by this because you did Play Ball, which is a sports baseball manga, and you mentioned you're a big fan of Mitsuru Adachi, who’s done so many amazing baseball comics, even stuff with romance. The biggest baseball manga right now is Yūji Terajima’s Daiya no Ace, or Ace of Diamond. Are you a fan? How do you feel about sports manga? Are you into it? Takehiko Inoue did it, so many have done it, and you’ve mentioned you’re a football fan. There’s Ao Ashi [a footballer manga] by Yūgo Kobayashi in Weekly Big Comic Spirits.

I’m a huge fan of sports manga. It dumbfounds me that it’s not big outside of Japan. I don’t know why American people are not drawing manga about the NBA.

ARI: Yea totally, or the NFL.

Exactly, or here in Spain. Why isn’t anybody drawing a manga about Messi and Iniesta and all of these people? I don’t understand.

RITESH: A La Liga manga, yeah.

I discovered Touch by Mitsuru Adachi. When Captain Tsubasa played on TV, they also played Touch. Nobody watched Touch, probably only me. [Laughs] Everybody watched Captain Tsubasa, but that Touch series got me obsessed with Kōshien [high school baseball tournaments] and with baseball manga. That started a lifelong obsession, to the point when in 2018 when I first went to Japan, the only place I knew I had to go to was Kōshien Stadium. If you look through my social media, you’ll find a picture of me at Kōshien Stadium, and I am so proud of that. But the fact that we got manga about sports, that’s something that we never saw in the west. One of the things that fascinated me the most-- and it’s not the kind of manga that I’m more drawn towards today, as sports manga tends to lean more to shōnen manga for the most part. But they’re so smart to exploit such a big field of so many sports. Football, baseball, gymnastics, they’ll turn anything into a manga!

RITESH: There’s comics about everything, like Chihayafuru about karuta [a centuries-old card game] or Hikaru no Go about Go or Akane-banashi about rakugo [a style of live comedy performance]. All of these things, any hobby. There’s a shoemaker manga titled IPPO, a wine manga called Drops of God. It’s endless.

ARI: Right, Drops of God came out in Morning, in the magazine that you’re working for, and it’s over 50 volumes about wine. You can make a manga about anything. It’s super popular.

It’s insane, right? I worked as an assistant for a manga called "Superman vs. Rice" (Superman vs. Meshi: Superman no Hitori Meshi), a DC licensed manga, and the manga is about what Superman does when he’s done doing superhero things. Then he goes and eats at restaurants, Japanese restaurants. It’s all kinds of crazy things. Those are things that only mangaka do. That’s one of the things that attracts me the most to the Japanese manga market. The fact that right now I am doing a crazy manga about an old man who plays videogames, but the fact that if this series gets canceled at some point because it doesn’t sell or whatever, the fact that I have the opportunity, potentially, to do a story about anything, anything.

RITESH: Exactly. Cooking Papa or Oishinbo or Food Wars! - food manga is a thing, which doesn’t exist as much in the mainstream comics of the west.

Exactly, and the fact that-- Play Ball is an example. Play Ball was rushed, and I can see so many things wrong with it, but it was well-received by Japanese editors because you take a well-known world and then you focus on something. Why is such a big field like sports explored in all those kinds of ways? I’m talking about the potential for professional competition, you can do a manga about that. The pressure that people feel behind the scenes, a manga about that. The coach-- one of the biggest mangas in Morning is Giant Killing [another football series].

RITESH: Yeah, Giant Killing is amazing. Very manager-focused.

Exactly. I just don’t understand why Americans are not doing that. The fact that I am starting to play in a field now where I have all of those toys is really exciting. Will I be allowed to play with them? I don’t know if they will let me, but I will try.

RITESH: Yeah, and Giant Killing is amazing because the lead, Tatsumi, is almost like an anime Mourinho kind of figure. He is a defensive-minded coach who can lead scrappy players and teams to win, so it’s fascinating that there’s all of these things.

Yeah, the Japanese have the ability to make anything exciting in a manga. They can take ping-pong and try to make the most epic manga—and animation series by the way—in the hands of Taiyō Matsumoto. So I don’t know why, if you go to American comics or even European [comics], and you tell people you want to make a comic about football or about ping-pong, they’ll look at you funny. Like why? It’s not going to make money, but even artistically, they don’t see the potential of you telling a story, a potentially exciting, epic, touching story, about something like ping-pong or any other sport.

RITESH: Yeah, that’s a shame.

It is a shame. It is a shame because even-- I don’t know about America, but even [in Spain], most sports manga don’t get translated either.

ARI: Some do in English, but not a lot. Some are fan-translated or translated online unofficially. Slam Dunk, Ace of Diamond have official translations now.

RITESH: Giant Killing also has an official translation, but at the same time, most translation also tends to happen in French because France has a big tradition of that sort of thing, but definitely not in Spanish or English.

Not in Spanish. I know that Captain Tsubasa got translated and published, but not a lot of people cared. Touch was canceled. It was first published in the '90s and only nine small issues got printed. Then it got published by a really really small publisher in the early 2000s with the four big omnibuses, but it looked like an amateur job. It looked like people who said, “We want to be a publisher because we like this.” Then the publisher closed down, so it was a poor job. It baffles me because we all like sports, we all like football, we all like basketball, and I don’t know if it’s because the fanbases don’t overlap, maybe. Maybe the people who like sports don’t like manga, but I like sports and I like manga, so I don’t know. I can’t be the only one, right?

RITESH: Yeah, you can totally make a manga about Real Madrid vs. Barcelona, for instance. It totally works. The Derbys are like a warzone.

Right, exactly. But I don’t know. At least here, there’s no culture about that. In Japan, you go to the subway and you see everybody with a cell phone or a tablet or a manga in their hands. You never see that here, never. In America either, so I think that’s the difference.

RITESH: Comics are a different thing in the context of Japan as opposed to a lot of other places, for sure. I remember earlier you were talking about the person you initially started working with in manga, one of her clients was a suit company, and they wanted to promote their suits with manga. That’s so unusual and you don’t see that anywhere else, I don't think. Nobody says, “We want to make a comic to promote our suit.” That’s a strange idea, but in Japan, that’s common.

It is. They use manga for everything. Actually, one of my contacts in Japan started a company like that. They advertise themselves by saying, “Okay, we can make a manga for you to advertise your product.” The same way here you would use a YouTube video or a book or an ad on TV. If they want to get traffic on their website, they say, “Okay, every week we will publish, only on our website, a manga.” In this case, it was a manga about, of course, the suits, but the suits had some sort of powers and they went to a place with a lot of dragons, like a Middle Earth sort of thing. It was really crazy, but it was all tied up with the fact that those guys were into suits. So in the end, they were just publishing in LINE, social media, Twitter, everywhere. Every week they had a new chapter and tried to generate traffic to their website. I don’t understand why we don’t see the potential here with that, but I think it’s because so many people read manga. If a company says, “Okay, we’re going to make a comic about whatever,” who is going to read it? Especially in Spain, people read comics but it’s not playing video games or watching TV or going to the movies. It’s not as mainstream a medium of entertainment.

RITESH: Now you work for Kodansha, which of course is such a huge publisher. Do you see yourself, or do you want to work for Shueisha or Shogakukan in some capacity?

RITESH: Right, which did not get approved.

Exactly, so I’ll try anything. If they allow me to somehow bring a little part of me to the story that I’m telling so that I care about it, then it’s fine. The shōjo story was a very simple, superficial story for girls, but at the end of the day it’s about culture shock, which is what happens when a Japanese person goes to Spain or when a Spanish person goes to Japan, and I have experience with that. It didn’t get approved, but I tried to show a little bit of Spanish culture to the potential Japanese readers. If Kodansha allows me to do that kind of thing; if they allow me to put a little bit of Kamen Rider here or a little bit of Ultraman there; if they make the effort to make the story a little bit about my background, which is what they’re doing, then I’m happy. This e-game world that [Matagi Gunner] is set in, of course anybody can play online. Not all of the teams are going to be Japanese. They’re going to be teams from everywhere. The big villain team right now is from Barcelona, and to me that’s a lot of fun. I can put a lot of things in there from my background, so I don’t see myself going anywhere.

ARI: Thank you so much for taking the time. We really appreciate it.

RITESH: Absolutely, yeah.

Thank you. Trust me, I am as surprised as you are to be doing this. I wake up every morning and say, “Wait, I work for Kodansha?” I realize what it looks like from the outside and it’s been a big process from the inside, but it is still surprising to me that I am able to do what I’m doing. There hasn’t been a lot of awareness about this and nobody around me like my family or friends really understands what this is. It’s not just another comic. Because they don’t understand that, I don't have anybody to talk to about this. I don’t even have time to go on social media and talk about this, so the fact that you allowed me to think and talk about it and are interested in me and what I’m doing is great.