Some cartoonists are naturals and by the time they’re in their teens are already turning out great stuff. Others have to work at it. Gil Kane always thought he was in the latter category. Even after he had become one of the most popular and successful comic book artists in America, he still felt he could do better. “I think that my triumph was that I was lousy early on,” he once said in explaining why his drawing had so greatly improved. “It wasn’t until I really started to work out systems, to really question the work.”

He was born Eli Katz in Riga, Latvia in 1926 and spent his boyhood in the Jewish immigrant section of Brooklyn. He “grew up feeding my imagination on the inspired work of my personal gods of the time: Hal Foster, Alex Raymond and Milton Caniff.” By his mid-teens, he was working in the comic book field. He freelanced for MLJ, doing mostly donkey work, and put in time at the art shops of Jack Binder and Bernard Baily (where Frank Frazetta was employed a bit later). He also worked on the features Joe Simon and Jack Kirby were producing for DC: The Newsboy Legion and Sandman.

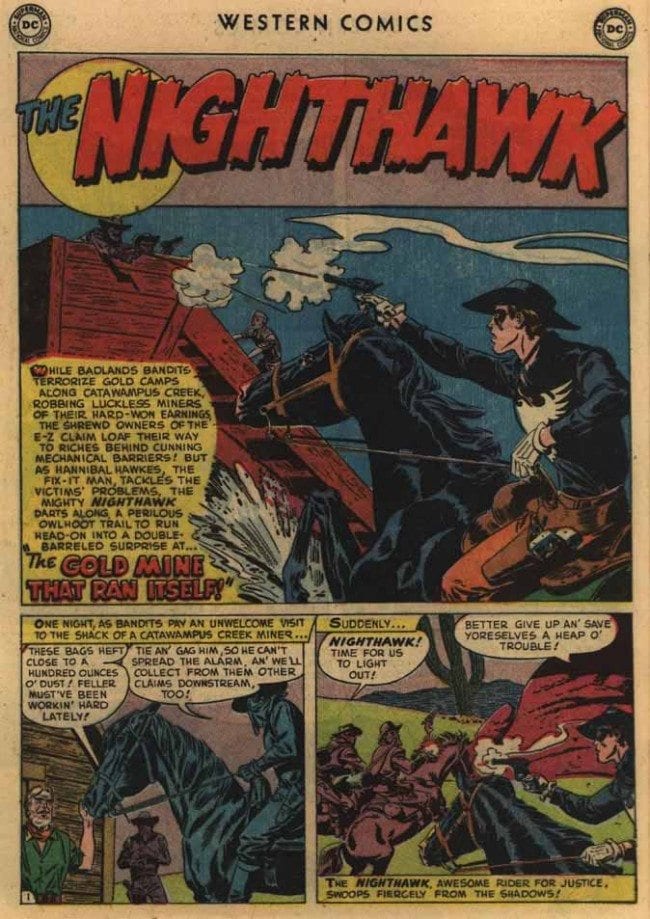

In 1947, he and his friend Carmine Infantino took their samples up to Sheldon Mayer, the editor of the All-American division of DC Comics. Mayer had been a boy cartoonist himself a few scant years earlier. He thought Gil had potential and gave him a tryout. (Infantino he told to come back in a year or so.) Gil Katz was assigned Wildcat, a boxer/costumed hero created by the team of Irwin Hasen and Bill Finger. He still hadn’t decided on a suitable name and signed the Wildcat adventures Gil Stack. Within a few more years he settled on Gil Kane and was drawing a great many features for DC. Much of that was in The Western category during the period when superheroes were floundering and cowboys ruled the scene. He drew Hopalong Cassidy, Johnny Thunder, The Trigger Twins, etc. Kane had been fascinated by comic strips like Red Ryder and King of the Royal Mounted when a boy. One of the things he prided himself on was his ability to draw animals, particularly horses.

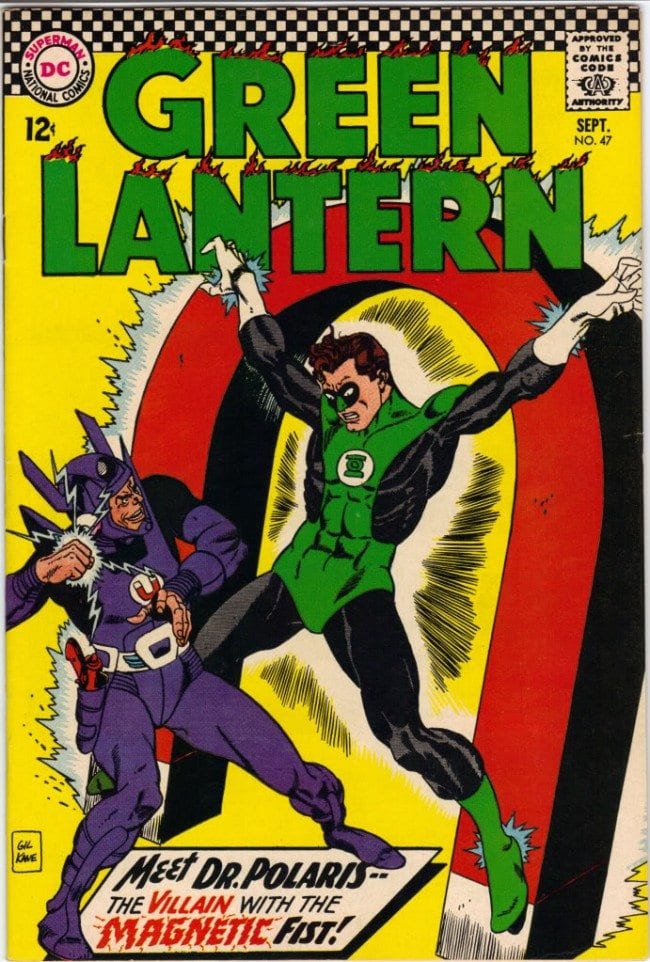

The character that won him his first big audience was Green Lantern. A Golden Age retread, the superhero was revived and refurbished by editor Julius Schwartz in 1960. Schwartz had also been hired by Sheldon Mayer. He had already brought the Flash back to life and felt there was once again an audience for super guys. He proved to be correct and his work as a resurrection expert started the Silver Age in comics. Schwartz picked Kane to do the artwork and had him redesign the born again hero. Kane’s work had improved noticeably, yet what he was doing at that point was a very slick version of the DC house style.

Kane’s real breakthrough came in the mid-Sixties, when he did a number of features for Tower’s short-lived T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents. He had finally arrived at the detailed bravura approach that he stuck with and built on for the rest of his days. “I began to become interested in structure, placement,” he said about the changes in his work. “Everything that had to do with understanding how things worked and what they looked like underneath. And that for me became a point of views. I worked out of that attitude and I think it’s made me what I am today.” He added, “In the beginning, what I hated about my work was that it was so timorous… I began to make up my mind and come to terms with what I really wanted in the work, and I began to put everything together.” Kane moved over to Marvel in the 1970s to draw Spider-Man, Ka-Zar, Conan, Warlock, and a host of others. He was also their premier cover artist, eventually creating something like 700 of them.

In the summer of 1976, before anyone had heard of Star Wars, I was approached by the feature editor of the NEA syndicate, who had decided that what newspaper readers were ready for a new science fiction strip. Possibly one with a little humor. Since I had been writing humorous SF novels and stories for over three decades, I figured I was the man for the job. I later find out that they had tried to get the comic strip rights to Star Trek and couldn’t come up with the asking price. So what was wanted was a strip about a bunch of folks wandering around the universe in a spacecraft. After having met me on a trip to Connecticut, the Cleveland-based John “Flash” Fairfield offered me the job of developing such a feature. He had two other requirements. In order to emphasize the artwork, the strip had to be two tiers high, twice the size of any other strip in existence. And it was to be drawn in the style Alex Raymond used on Flash Gordon; possibly NEA could get someone like Al Williamson, the leading exponent of that style. Gil Kane had moved to the same town in Connecticut where we were living at the time, along with his wife, their children and his mother. I’d gotten to know him and he said he had read some of my books. He got me some assignments from Roy Thomas at Marvel.

A time when adventure strips were dying and funny ones were filling their slots was probably not an ideal time to try to peddle a jumbo one. But, since it had long been my ambition to write a comic strip, I did not share my thoughts with Flash Fairfield. I did, however, suggest that instead of a Raymond idolater, NEA hire a popular contemporary comic book artist who was steeped in science fiction and drew in an up-to-date manner. Specifically, Gil Kane. Nobody at NEA had ever heard of him, but when they saw samples of his work and learned that he’d drawn Spider-Man, they were impressed. NEA and United Features had a dinner for all their Connecticut artists, writers and executive. After the dinner Gil and I were invited to have drinks with some of the visiting executives. One of them asked Gil if he could send him a drawing of Spider-Man for his grandson. And he said, “My boy, I’ll draw it for you right now” and turned over the large paper place-mat and drew a complex drawing of Spidey swinging through a Manhattan nightscape. The executive was obviously delighted. And I thought, “We’ve got a deal.” And we did.

I had done a synopsis of the strip before Gil came aboard. My strip was titled Star Cops and featured the team of Ben Jaxon and Chavez, who were interplanetary lawmen stationed on a huge spacecraft called the Hoosegow. Flash and Gil didn’t like the title or Jaxon’s first name. Gil and I had been fans of Basil Wolverton’s Spacehawk in our youth so the name was changed to Star Hawks. It was Gil’s opinion that interplanetary heroes didn’t have first names like Ben. Rex was a better name for a hero. I pointed out that Rex was the name for a dog. But even though Gil had drawn Rex the Wonder Dog for DC, he held out. Our strip became Star Hawks starring Rex Jaxon and Chavez, who never had a first name.

Next I wrote a few weeks' continuity and Gil drew a couple of finished strips and several penciled dailies. They were shipped off to Fairfield at the NEA offices in Cleveland, Ohio. And there they sat, gathering dust for several months. Then Star Wars opened in movie houses and was a smash hit, a blockbuster and several other superlatives. Multitudes of eager customers filled movie theaters after waiting in long lines to get in. NEA syndicated a short serialized text version of the movie and that too was a smash hit. The higher-ups at the syndicate asked Fairfield if he could come up with something else in the science fiction line. “I already have,” he replied, brushing the dust off our proposal. Within weeks Star Hawks was appearing in newspapers all over the country.

But not quite enough of them. The New York Post, the Detroit News, the Washington Star, and several other large papers signed on. But a great many editors said that it was a terrific strip and Gil’s art was terrific but it was too darn big. In order to shove it onto their comics pages, they’d have to dump two normal-sized strips, maybe Beetle Bailey and Blondie, maybe Garfield and Nancy. So the strip wasn’t earning a substantial profit and Kane had to keep working for Marvel while working on the strip. He kept on putting in twelve-hour days at the drawing board and finally collapsed and spent two weeks at the Norwalk Hospital. I left the strip after about two years, Archie Goodwin assumed the scripting and Kane stayed with the art. Star Hawks struggled on for another two years. Kane also took over the Tarzan Sunday page, adding even more work to his schedule. In its heyday Star Hawks was a very good comic strip; the writing was okay and Kane did some very fine and inventive drawing. He won a National Cartoonist Society award in 1978. And there has been no strip quite like it since then.

He worked for both DC and Marvel during the rest of the century. DC allowed him to do one of his long cherished projects. He was a dedicated opera lover (he often listened to operas and classical music while at the drawing board) and he was finally able to draw a four-issue adaptation of Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung. He and his family moved to the Los Angeles area eventually and he went to work for Ruby-Spears Productions, who produced animated kid television shows. Other comic book veterans, such as Alex Toth and Russ Heath, were also active in animation. Kane specialized in character designs and presentation pieces.

I lost touch with Kane for several years, running into him again at the San Diego Comic-Con late in the 1990s. I spotted his wife, Elaine, in the crowd and noticed that she was with a thin, bald man who resembled Gil Kane. When I joined them I found out that it really was Kane and that he was in remission from cancer. They invited me to have dinner in an Italian restaurant in Hollywood a few nights later. Gil, though appearing frail, was as voluble as ever and held forth on his opinions of the current state of comic books, the world situation, and the effects of his illness on his career. Elaine told me that one of the independent publishers who wanted to hire him had insisted that he get a signed letter from his doctor assuring them that he was going to live long enough to finish the job. They moved to Florida, and Kane, though ailing again, continued to draw. His last drawing was for a series of covers for DC’s Legends of the DC Universe. Those appeared in 2000, the year of his death.

Warren King was probably the only artist ever to have ghosted a political cartoon that was awarded a Pulitzer Prize. He grew up on Long Island, attended Fordham University and trained as a painter. He has said, “Next to painting, drawing editorial cartoons is my greatest gratification.” Be that as it may, King drew a string of superheroes, as well sa romantically inclined young women in some romance comics. From 1940 to 1944, he drew for such MLJ titles as Blue Ribbon Comics, Top Notch and Pep Comics. He illuminated the fantastic adventures of such second-banana costumed heroes as The Fox, Black Jack, The Wizard, Captain Flag, Hangman, The Firefly and Mr. Justice. A middle-sized stocky man himself, most of his characters, even the women, were long and thin. In the El Greco and Modigliani tradition. King broke up his pages in unusual ways and avoided the standard grid. In the Fifties he turned to romance and turned out love stories for St John titles: True Love, Pictorial Romances, and Diary Secrets. The sexy-girl specialist, Matt Baker, was there as well.

King worked in advertising before joining The New York Daily News in the middle 1950s. Abandoning humorous comic strips, intricate inventions, and foolish questions, Rube Goldberg had turned himself into an editorial cartoonist. King was his assistant and sometime ghost and drew the cartoon that won Goldberg his Pulitzer in [1953]. After Goldberg went on to conquer new mediums, like humorous sculpture, King took over the daily political cartoon and moved to Wilton, Connecticut. The News was an aggressively conservative newspaper and he drew many cartoons critical of Pinkos and Vietniks. King was married to a woman who had been married to Joe Blair, a writer for MLJ. The few times I met her, she championed the MLJ comic books of the 1940s. Warren King was friends with Leonard Starr and Gil Kane, men more liberal than he. He died in Wilton in February of 1978.

On July 1st of 2015, I was asked by The Comics Journal if I would write an obituary for Leonard Starr, who had passed away the day before at the Meadow Ridge managed care facility in the nearby town of Redding. He and I were not close friends but I had known him for many years and worked with him on the Thundercats! kid television show.

I’d first met him through Gil Kane, a close and longtime friend of his. He’d helped Gil with inking when our Star Hawks comic strip was just getting underway and Gil needed, as he often did, some aid in meeting his deadlines. Now and then I’d drop in on Starr at the smoke filled second floor studio he was sharing with Stan Drake on the Post Road in Westport.

This account of his life is based in part on that 2015 obit, with the addition of material I’ve picked up since. Although the soap opera comic strip had begun with Mary Worth in the late 1930s, it was in the late 1950s that Leonard Starr created the best-drawn and best-written one with his Mary Perkins, On Stage.

He became a professional cartoonist while still in his teens. When in 1942, he began working in the field, the industry was still expanding and Superman was only four years old. A native of New York, where most of the comic book action was, he broke in by drawing for two of the pioneering art shops. The first was run by Harry “A” Chesler, a man of dubious reputation. The other was Funnies, Inc, a much more reputable outfit. It was run by Lloyd Jacquet and Bill Everett was art director.

This shop provided art and editorial for, among several publishers, Martin Goodman’s Timely line. Starr assisted on such heroes as Human Torch and Sub-Mariner. Like several other young men who became comic book artists, he had studied at the High School of Music and Art in New York and the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. Eventually dissatisfied with the quality of his work, he enrolled in the Art Students League in Manhattan. Throughout the Forties he sold to a variety of publishers. Large and small. Among the titles he appeared in were Red Circle, Liberty Comics, Airboy, Young Romance (for Joe Simon and Jack Kirby), Adventures in the Unknown and Crown Comics. He teamed up with Frank Bolle on some of these jobs and for Crown they had a feature about a tough private eye and one about a mystical jungle man.

Starr had early been influenced by Milton Caniff and he developed a modified style that was much influenced by Terry and the Pirates. As the Fifties started, he added DC to his list of clients and started appearing in such titles as Tomahawk, Gang Busters, and Detective Comics. His drawing had acquired a new vitality and he gave the impression he was enjoying himself. His women characters, whether femmes fatales or damsels in distress, were increasingly attractive and indicated what one of his strong suits would be when he graduated to a comic strip of his own.

It was the ambition of many comic book artists of the time to move up to a newspaper strip. Several of his contemporaries had already made the transition: Ken Ernst, Stan Drake and Dan Barry. Finally in 1957, Starr sold Mary Perkins, On Stage to the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate. The title of the strip alludes to two of the post popular radio soap operas of the day: Mary Noble, Backstage Wife and Ma Perkins. Starr had long been a theater buff and the new strip would deal with “the glamorous New York theater world.”

His style had changed, moving toward what has been called photographic realism. He was in influenced by what Alex Raymond had done on Rip Kirby and what Dan Barry had done on the daily Flash Gordon in the early Fifties. Starr has bee called “a man with a superlative ink line.” His staging of the events as pretty Mary Perkins conquers Broadway, television, and the movies (and finds love) is very good and he alternated light continuities with some dark and unsettling ones. Writing in The Encyclopedia of American Comics (1990), Dennis Wepman said that On Stage “was one of the most maturely written and elegantly drawn continuity strip in American comics.” He pointed out that it “transcended the conventions of the sentimental romance and the tearjerker, incorporating elements of high comedy and often gripping adventure and suspense.”

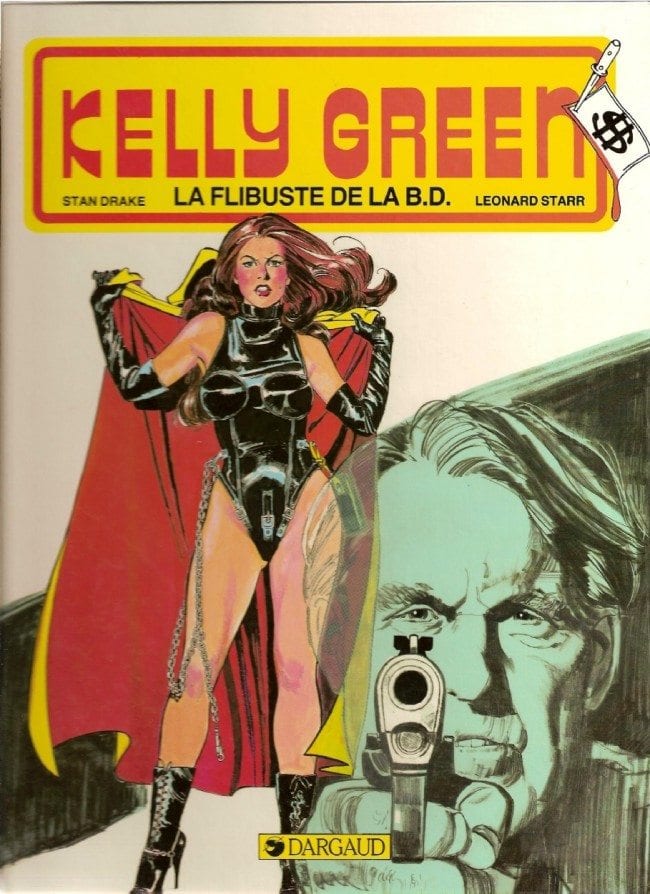

Starr ventured into graphic novels in the 1980s and wrote five adventures of a sexy, tough. red haired and often unclothed lady adventurer named Kelly Greene. Like many a leading lady in those days she had “big hair.” These were done for the French graphic book publisher Dargaud and had both European and American editions. Stan Drake, Starr’s studio mate did an impressive job on the art. And since this was not an American newspaper strip like his The Heart of Juliet Jones, he could draw his female characters in a variety of states of undress.

The National Cartoonist Society gave him its Best Story Strip Award in 1960 for On Stage and in 1965 a Reuben as Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year. By the 1970s story strips were declining and funny stuff was multiplying. Mary Perkins stayed on stage longer than many story strips but in 1979 the syndicate decided to ring down the curtain. But just a few months later that year Leonard Starr was back on the comics pages now drawing Annie, an updated and modified version of the life and hard times of Little Orphan Annie. The title had been shortened he explained “to make it seem less dated and to refer to the highly successful Broadway musical.” He drew Annie in a more cartoony style and as a tip of the hat to Harold Gray, his Annie had blank eyeballs. It was a handsome job and a good looking strip. Starr retired in 2000 from the strip but the redheaded waif hung on for another ten years.