The last published Krazy Kat strip appeared on June 25th, 1944. When Herriman passed away on April 25th of that same year, he was working on an unfinished pair of daily strips. But Sunday strips are drawn in advance, so the June 25th strip is the final communication from (in my opinion) the world's greatest cartoonist.

The final three Sunday strips have a lot to say, about the strip itself and about living in general. I think a close read of them might illuminate something that seems to be obscure about Herriman. Krazy Kat holds much more than people grudgingly give it credit for. Its importance doesn't lie in the 'eternal love triangle' literary device of Krazy, Ignatz, and Pup (the only aspect of the strip major media outlets bother to write about---hey, it's an easy subject to fill a paragraph with before going on to explain how unpopular the comic was in its time). Nor is it proper to end discussion of the strip by saying it's 'beautifully designed!' which I hear a lot when people profess to not understanding the strips appeal but halfheartedly try their best to find something in it to connect with. Both of these common reads on Krazy Kat miss the forest for the trees.

One way to begin our approach is to consider that Krazy Kat might be the greatest comic strip of all time because it is unapologetically told exclusively within the language of cartooning. Herriman is not a Cliff Sterrett-esque stylist nor is he concerned with grafting literary devices onto the Sunday comics page. Krazy Kat is a solar system---it doesn't mirror or pay homage to anything else but its own thought---and its thought is expressed by one of the key architects of what we think of as cartooning. Krazy Kat was the crowning work of a newspaper strip veteran, whose first comics were published in 1901, at the dawn of the new medium. This column previously discussed Lionel Feininger, another architect of the form. But what distinguishes Herriman from Feininger (a painterly approach to cartooning) or Sterrett (modern art filtered through cartooning) or Winsor McKay (how visually astounding can this be?) or Bud Fisher (vaudeville humor as comics) is his adherence in Krazy Kat to nothing but the system of cartooning he and his peers developed. While Fisher's work reads like a two-man comedy act translated through reoccurring caricatured figures appearing in sequence, Herriman discards vaudeville. All that remains are the cartoon figures in sequence, drawn to the same scale day after day, and, importantly, the interactions of these characters. Sterrett mixed 'Cubism' with a cast of eccentric characters to great comedic and visual delight, thus providing not only a domestic reference to agreed upon reality, but some recognition of artistic trends or concerns happening outside of the world of his characters. Not so with Herriman. Instead of filling his strip with nods to the world as it is or falling back on the 'seriousness' of other forms, Herriman instead infused the systems of cartooning (which he helped to invent) with himself, his own thoughts and feelings. Yes... the real world is present in the strip, but as seen in Herriman's mind rather than by the standards of the day.

Herriman, make no mistake, is not freely improvising his thoughts, Beat poetry style, onto the page. There is great precision and elegance employed in placing his life project into the system of comics. Furthermore, this is not an artist who is writing literary monologues and adapting them to the form of cartooning. Instead, the simplified cartoon characters, through their interaction, elicit feelings. The 'triangle' is there, but it goes far beyond device. I do not think what's at play here are 'human relationships being explored' but rather emotions and thoughts brought out from the reader that are created through the cast's actions and reactions. Like all important art, Krazy Kat makes into reality charged emotions or concepts that didn't exist before the strip was read, but impact us (whether they 'make sense' or not) after they are digested. Poetry? Sure. But of a unique kind, so that it seems unfair to paint the strip as simply that and call it a day. Instead, let's explore the strip's final days to see a prime sequence of the notions it creates.

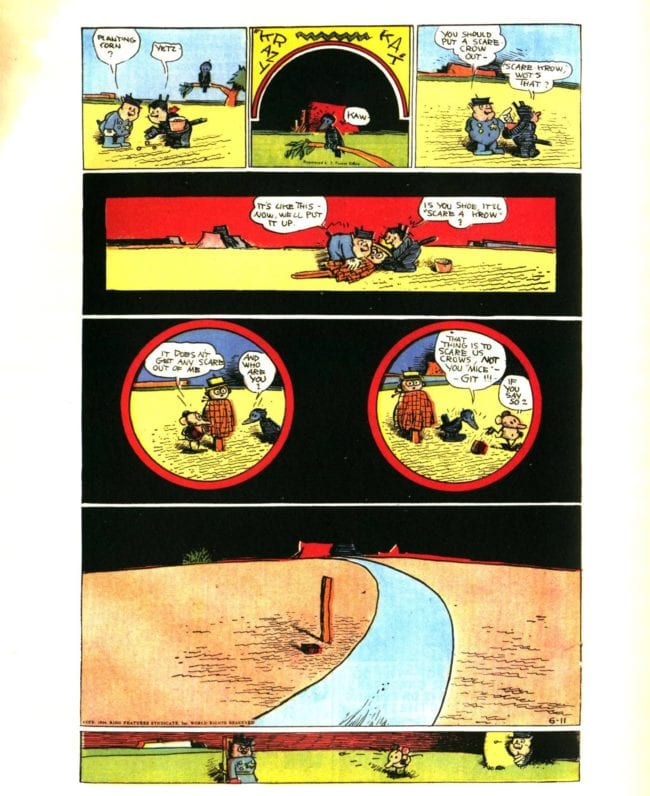

Jeet Heer, in his introduction to the Fantagraphics collection of the final Krazy Kat strips, Krazy & Ignatz - He Nods in Quiescent Siesta: 1943-44, says that "the last two strips are surprisingly melancholy." Putting aside the more general wrongheadedness of saying that melancholy was a surprising feature in Krazy Kat (a strip that contained all emotions, regularly---and, as we will see, the events in these final strips are far more charged than the 'melancholy' alone suggests), Heer is wrong to focus our attention simply on the final two Sunday strips. The sequence that leads to the strips crescendo begins with the third to last Sunday strip, published on June 11th 1944.

The strip leads off with Krazy planting corn, as Offisa Pup observes. Throughout 1944, there had been constant references to vegetation, trees and crops growing. In fact, the final time Ignatz strikes Krazy with a brick on May 7th, 1944, it's from a clever trick where Ignatz instructs Krazy to place a brick on top of a quickly growing tree---it sprouts up and the brick topples off, onto Krazy's head.

The next week, the final time Krazy seems to respond or hear something Ignatz says, Krazy's notion that another quickly growing tree is an oak tree is confused by Ignatz remark to Mrs. Kwakk Wakk about olive seeds turning into olive trees.

Instead of a tree cropping up quickly, as had become more of a feature in the strips later days than bricks hitting Ignatz head, on June 11th Pup and Krazy prop up a scarecrow. A familiar (albeit new) feature of the strips logic is being subverted.

Upon seeing the scarecrow, Ignatz remarks that 'it doesn't get any scare out of me,' though his face suggests otherwise. The crow remarks that it's not meant to scare a mouse, it's meant to scare crows. Strangely, Ignatz accepts this and leaves, while the crow stays. The scarecrow designed to scare crows and not mice repels the mouse while the crow remains. Given the emotional make up of the strip, I feel like something else is going on here: Ignatz face reacts to the scarecrow nakedly, then reverts back to being collected, as if the true meaning of the scarecrow is grasped instantly, but can't be uttered. Ignatz' actions, however, speak volumes. He's not scared and yet he puts down his brick and leaves. The next panel is totally silent and empty. All that remains of the scarecrow is a stick.

The scarecrow's absence suggests that its purpose was accomplished. Ignatz has been prevented from going further. What's more, Ignatz's brick sits next to it, unused. Never again will we see Ignatz with his brick in the strip. The silence of the panel draws our attention to an important event transpiring here. I can't think of any other Krazy Kat panel that is not only silent but devoid of any of the strip's characters. One of the main narrative drives of the strip has ended forever. Was Offisa Pup finally successful in driving off Ignatz for good with his suggestion of a scarecrow? Or is there something in the scarecrow's meaning that is a communication from Krazy directly to Ignatz, signaling to the mouse that their 34-year interaction is now deeply changed? I don't know how to come down on either side of things here, but it's worth looking at the last two times Krazy and Ignatz have communication of any kind in the light of these questions. While the May 14th strip is the last time that Krazy is seen to consciously hear Ignatz, their actions affect each others two times more before the final break on June 11th.

On May 21st, we have a particularly stark statement from Herriman on race. (Herriman's life as a black man who passed for white has been explored in meticulous detail in Michael Tisserand's densely researched book Krazy: George Herriman, a Life in Black and White. This column can't begin to address the subject in even a fraction of the detail Tisserand has, so please consult that book for far more on this subject). References to race appear throughout Krazy Kat, but rarely more explicitly than they do here. We see Krazy observe a brown weasel, who is, as Offisa Pup explains, a poor insurance risk because of his color. Krazy remarks that this is odd to him. The rest of the strip shows Ignatz stepping in and facilitating the weasel's transformation to white. Krazy observes the transformation. Ignatz remarks to the weasel that his new higher value owing to his color is 'the way of the insurance co. Queer but still their way.'

I'm against simple interpetations, but Ignatz's involvement in these actions that are of great importance to Herriman must be at least considered. Ignatz's readiness to respond to changing someone's color and his understanding of the issue in the face of Krazy's bafflement mean something. Whether it's anger or confusion over the issue that leads to Krazy (perhaps by accident) repelling Ignatz three weeks later is unclear to me, but, again, must be considered.

Two weeks after the weasel incident, we have a particularly jarring strip. Offisa Pup uses a stick as a diving rod to unearth a brick, which in his mind Ignatz will no doubt use against Krazy. It appears to me the same stick that props up the important scarecrow. The final panel of the strip suggests that Ignatz was also... buried underground? As Pup (holding the stick and the brick) and Ignatz walk away, Ignatz's head emerges, in apparent anguish.

The strip that follows is June 11th, with the stick now re-purposed to prop up the scarecrow. So, the final interactions of Krazy Kat and Ignatz map out like this: Ignatz tricks Krazy into getting hit by a brick toppling from a growing tree, Ignatz passingly confuses Krazy about oak trees vs. olive trees, Ignatz works to transform a weasel's color in an issue whose subtleties are (seemingly) obscure to Krazy and finally Ignatz' brick is discovered with a stick from Offisa Pup while Ignatz writhes in agony, his body beneath ground. After these events, the scarecrow emerges and Ignatz discards his brick. For a brief moment the strip is silent and empty.

This brings us to the final two strips.

The June 18th strip begins with Offisa Pup and Ignatz in rare agreement. Krazy Kat is submerged in water. 'I know it,' says Ignatz. Both Pup and Ignatz dive in to save Krazy... except, Krazy is not under water after all. He's standing next to the lake. Ignatz says that they were 'saving' Krazy, and yet the strip seems to suggest that it's a prank by Ignatz. In the last panel, we see Offisa Pup still in the water---did Ignatz trick Pup into worrying about Krazy only to have him dive in and look hopelessly for a Kat who was never there? Ignatz knew to climb out of the lake immediately, while Pup seems to have stayed there for a while before figuring it out. So... a prank, for now.

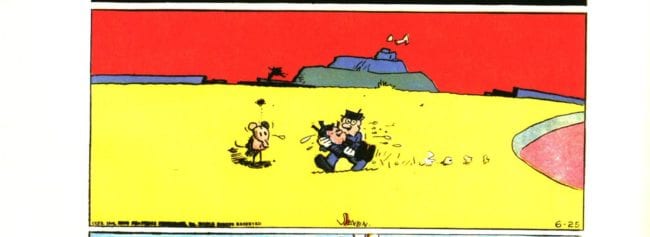

And yet in the final Krazy Kat strip from June 25th, it seems that things are more serious. Pup notices bubbles coming from the lake and at first dismisses them for another prank. In the next panel he either sees Ignatz, which makes him reconsider somehow, or he has a realization of his own. Either way, he's now convinced that Krazy is truly in the water this time. And he's right. When he returns to the lake, Krazy's head emerges from the water, eyes wide open, only to sink in again. Pup jumps in, and emerges with a very still Krazy, whose eyes are now closed.

Jeet Heer, again from his introduction to Krazy and Ignatz 1943-44, interprets the final strip as follows: "[Pup] realizes his mistake and rescues the cat, who is rendered completley and uncharacteristically silent by the trauma. Given all the wonderful words Krazy uttered during his (or her) life, the muteness of the last panel is eerie and evocative. The show is over and there is nothing left to be said."

With the context of what was going on in the world of the strip in its final months, I can't be as sure as Heer that Pup successfully rescued Krazy. Ignatz's expression and silence seem to point to a different conclusion. Pup himself is looking directly at the reader. He shares, I think, our pain. The show is over, yes, in the most clear way. With the silent June 11th panel as the catalyst, I feel that the trio has lost it's beloved leader.

And yet this is cartooning, so it's not that simple. Krazy and Ignatz were born from the bottom strip of The Dingbat Family pages. So, Herriman lets Krazy live on in the bottom strip of the June 25th strip. Look, here's Krazy! Back in the water! And holding... a stick.

All of these events hit me, as a reader, very hard. Yes, they are sad, like an actual death, but the feeling is not exactly tragic. The strips are emotionally hard to read, but why exactly? As discussed before, these are new feelings, that could only be discovered within this particular structure. Herriman's commitment to the beauty and potential of the medium he helped create becomes a limitless template for him to get at realities beyond reality. The strip's final days are first and foremost something to read and react to. Beyond that, we can point to them as an example of cartooning at its zenith, capable of true creation.

Why then does so much 'serious' cartooning take a different path? Of course literary melodrama, biography, journalism, action, etc all deserve to be explored in comics, and are often incredible works of art. Love and Rockets is a beautiful soap opera saga that I hold dearly. But where are the examples of pure comics that bring us such devastating events as the conclusion of Krazy Kat?

While I wouldn't put them on exactly equal footing, I do think the Superman titles in the late '50s and early '60s, under the editorship of Mort Weisinger, are examples of pure cartooning that deserve a mention when discussing this concept.

Weisinger's Superman group of titles was one of the most commercially successful lines of comics ever published. Children at the time read them in extremely high numbers, a level of sustained readership that will probably never be equalled for comics with caped characters.

The tone of the line defined itself in 1958, partly by a constraint that the comics world imposed on itself. Physical violence, while not banned by the comics code, was to be avoided. So Weisinger took a line of superhero comics and instead of emphasizing brawn, made them into intricate puzzles. Now, these are not puzzles that use the unreliable world as one of its factors in the way a Raymond Chandler novel might. Instead, every story has no relation to anything real (except basic outlines of things like 'I have a job at a newspaper' or 'humans need to eat food to survive' or 'ice is cold')---the comic book world of Superman itself is the only thing the stories use to set up their questions and render solutions. These are mysteries whose only logic is cartooning, and I'd argue that they are more beautiful as science fiction than anything EC ever published. EC's sci-fi line, edited by Al Feldstein and William Gaines, is endlessly lauded by comics people as an artistic passion project that was genuinely creative. In truth, the line was full of fine cliched stories with highly competent illustration. On their own terms, I adore them. Much good comics history is to be found in them, and a great deal of pleasure as well. But they weakly moralize, while Weisinger's Superman titles, which are generally looked at as kitschy trash, feel more like works of true imaginative genius. Like Krazy Kat, they achieve this through excluding the world outside of cartooning.

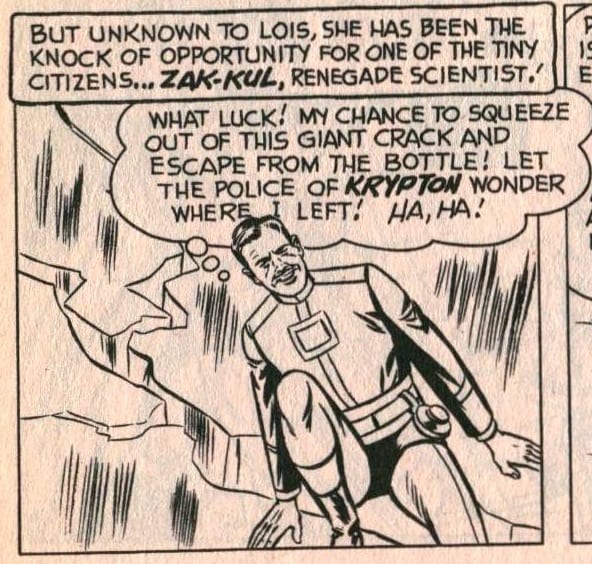

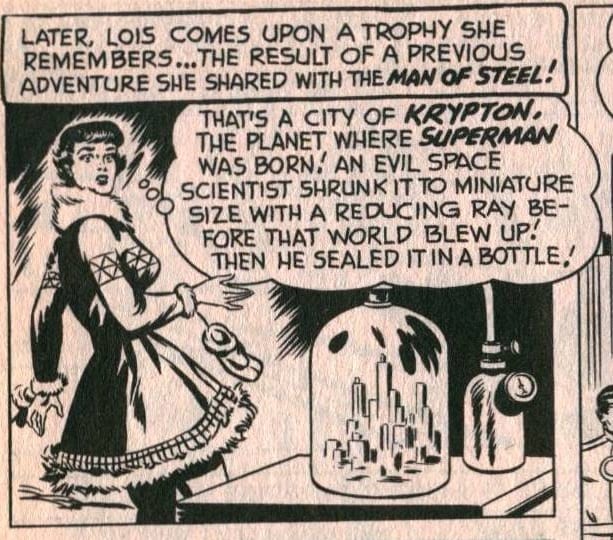

In 1958's 'The Shrinking Superman', written by Otto Binder with art by Wayne Boring, Superman brings Lois Lane to his Fortress of Solitude. It is filled with trophies and artifacts that exist within the context of Superman itself : trophies to Lois Lane, a bowling alley with a hundred pins instead of ten. No attempt is made to depict the elegant fortress of a powerful being, but instead everything is designed to emphasize the specific traits of this cartoon character. Lois Lane is his friend, so he has trophies of her. He's not ordinary so he has to bowl differently.

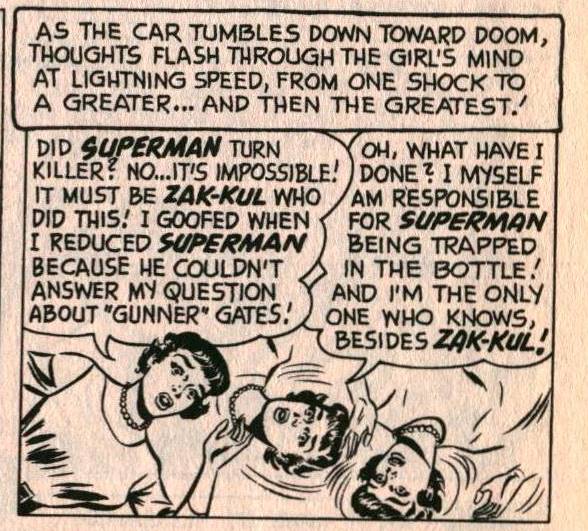

While in the fortress, Lois notices the city of Krypton, which has been shrunk to miniature size. It's simply another object from the series's history. Lois breaks the city open and a tiny villain emerges. He tricks Lois into thinking that he's Superman, as she reduces the real Superman to miniature size. This sets up a situation where Lois delivers the following information packed dialogue:

With work like this, there's an a degree of effort needed from the reader that's similar in difficulty to Krazy Kat. With Herriman, one must commit to the strip and put aside understanding things in an 'logical storytelling' way. With Weisinger's Superman books, we must make the effort to not read them as camp if we are going to enjoy them. These were stories made for children, but with a wild creative core. Superman as Killer/Zak-Kul/Reduced Superman/"Gunner" Gates/Am I Responsible?/Trapped In Bottle!/Only I and Zak-Kul Know! There are more ideas here in one panel than in a year's worth of contemporary mainstream comics, perhaps in a decade's worth. And, when these ideas are mixed together, the reactions they stimulate in the reader, while perhaps not as harrowing as those of Krazy Kat, are similarly unique. For a young reader, there is much to chew on here. The project Weisinger and his staff took on was not 'how to comment on the world' but rather the possibility of expressing something exciting within a system with multiple constraints placed upon it. Through those constraints, something that no other work of art could emulate happens.

Part of the success of these stories come from the deep care put into them. In the same way that Herriman was purposeful in arranging his universe, the vast amount of ideas brought into play in each Superman story is not executed messily but instead with deep precision. In this particular story, Otto Binder's script is crisp and precise, and Wayne Boring's art explains the action to the reader as clearly as possible. There is personality in both, but it's an undertone... a meaty, undeniable undertone, but not a focus. No frills. Boring's drawings communicate the meaning for that particular panel, nothing more. They pulsate but are modest, while Binder's scripts have a punch the clock vibe, imagination filtered through characters the writer was assigned to work on.

Binder's Captain Marvel comics for Fawcett were similarly packed with ideas, but they contained a lot of human warmth, a large dose of kindness. Under Weisinger, the human aspect is gone. Binder's Superman cast is closer to cruel than kind, but really neither. What we have on the page here is cartooning to the exclusion of all else.

The post-1986 idea of genre comics is deeply divorced from this, and I think that's why contemporary mainstream comics seem so adrift. Introducing 'the real world' into a system so charged up with its own distance from it is a nice one-time gimmick, to be sure. But as we pass three decades of the trick, the steady foundation it was based on feels unfortunately obscure. It's fitting that Watchmen #1 was published on the same date as Superman #423, which began Alan Moore's 'Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?' story. Moore (whose intentions where good, I think, and has moved beyond the 'gimmick' into ever-changing and very rich artistic territory) had the best Weisinger artist, Curt Swan, draw a story that aesthetically negates (in the form of homage) the imagination of the Weisinger years. 'Whatever Happened...?' is praised as an effective way to close the continuity of the Silver Age-era Superman to make way for the forthcoming revamp of the character, mixing the strangeness of the past with the awareness of the present. But that idea alone shows comic book artists and readers misunderstanding what was so effective about Binder, Boring, Swan, et al. For a world that is pure imagination, there is no need to end it effectively to make way for a corporate revamp. Those concepts are in opposition not only to imagination but to the potential of cartooning itself. Any medium can rationalize itself, but cartooning lacks any reasons to do so.

A drawing with pictures does not need corporate logic to express itself. Nor do artistic comics need to signal their seriousness by professing awareness of important this. Cartooning is rich and suffers when diluted.