Tom Spurgeon needs little introduction to readers of this site. He's the editor and writer of The Comics Reporter, one of the most popular and well-respected websites covering the comics industry; he was the editor of the print version of The Comics Journal from 1994 through 1999, a pivotal time for comics; and he is the co-author (with Jordan Raphael) of Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book. His writing is always intelligent, grounded in history, and infused with his personal experience. Everyone who has read Tom's writing feels like they know him.

Spurgeon has recently taken on a new role, as the festival director for Cartoon Crossroads Columbus (CXC), a city-wide celebration of comics art that in its first year has already established itself as a major event. It will be held again this weekend, and has attracted an impressive and wide-ranging guest list, including everyone from Garry Trudeau and Charles Burns to Carol Tyler and Stan Sakai.

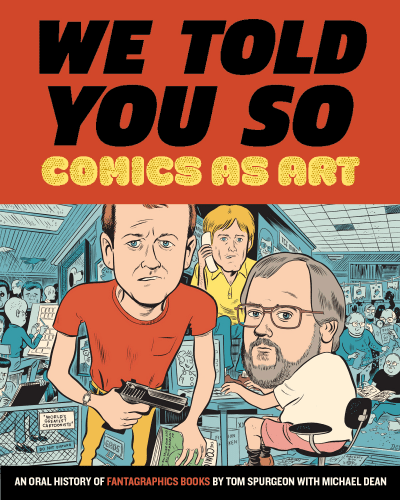

Spurgeon is also the co-author (with Michael Dean) of a new book, We Told You So: Comics as Art, the long-awaited and controversial oral history of Fantagraphics (publisher of this site) which will finally be coming to stores this December.

I sent Spurgeon questions via email about the book, the festival, working for Fantagraphics in the 1990s, his health, and his relationship with Gary Groth. He returned them in record time.

TIM HODLER: How exactly did CXC initially come together, and how did you become involved?

TOM SPURGEON: It comes out of the Cartoon Arts Festival that used to be held every third year for decades by the OSU library that is now the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. That was a sort-of secret festival held here in Columbus, very strip-oriented as you might guess given their primary holdings, and it was supported very strongly by the syndicates. It was basically just a series of presentations by cartoonists and comics-makers to an elite audience, and a lot of hangout time. I think at the earliest one they all went to founding curator Lucy Caswell's house for a meal.

Lucy moved into retirement from a full-time position at the Billy at roughly the same time the library and museum transitioned into the magnificent new facility AND the newspaper industry went right into the toilet. So a new model was necessary. A conversation by Lucy with her former student Jeff Smith and his wife, the force behind Cartoon Books as a business entity Vijaya Iyer, quickly expanded to rope in current Billy personalities Jenny Robb (the primary curator) and Caitlin McGurk, whose job includes outreach.

I get along well with Caitlin and Jeff and I think both of them take or avoid credit for bringing me on board depending on how well I'm doing.

What are your responsibilities?

I direct the festival, which means I'm primarily responsible for the logistics of it, the making it happen of it. That's both in just making sure stuff gets set up but also that we're executing according to our goals and ideals as stated. If I'm not on a committee, I'm being directed by a committee to do something or I'm in the room ex-officio offering advice and perspective based on the two-plus decade of ruining my life by paying attention to comics in its entirety.

How did you feel CXC went last year?

I thought we did really well for a first-year show, a two-day version of what we hope to become. Attendance was ahead of what I thought it would be (the figure we use based on our counts is 1200; I expected about half of that), and there were enough moving-stuff-around problems that it was really invaluable to have that under our belts going into a four-day model from now on. Just the basics. Like you forget if you go to a bunch of shows how much for most people stuff has to be explicit and easy to parse in terms of where things are and when and where to park, and so on.

Also, if you don't schedule time for dinner with nothing going on, some people won't eat! There's comics to do! I'll eat Tuesday!

What took you by surprise?

I was genuinely surprised in a good way how relatively sophisticated and smart we could get and audiences here even if they were unfamiliar with someone's work would roll with it. We sometimes think of comics as this obtuse, weird thing — and it can be — but a lot of what comics-makers do is a lot of what a lot of artists do. Of all types. And I think people that have interest in art beyond its consumption can accommodate some pretty advanced talk about what that means.

Also, people have a really refined aesthetic for food trucks. Who knew?

Last year, CXC was described as a "soft launch" or a "sneak preview" of what the show would eventually become, and at least one press report said the first "real" CXC show wouldn't take place until 2017. You've got some major guests coming this year—Garry Trudeau, Charles Burns, Raina Telgemeier. What should convention attendees and exhibitors expect? And are you out of the soft launch stage, or do you hope to expand dramatically next year?

I can't speak for everyone involved, but I felt we had to get pretty big pretty quickly for a couple of reasons. The first is that the convention/festival schedule is crowded as hell, and I thought we needed to make a case for our place on the schedule pretty quickly as opposed to last decade's model, where you could kind of grow the show for five or six years as the audience got used to attending.

The second is that one of the original conceptions is that this be a city-wide show. One of our explicit goals is to show off Columbus, even. So we run CXC out of about six venues in two different general locations: up on campus Thursday and Friday for the academic conference, peer to peer panels and auditorium presentations like Trudeau, then downtown Saturday and Sunday for the Expo part in our public library main branch with satellite events at the Columbus Museum of Art and Columbus College of Art and Design. We even move our late-night parties around.

The result is that there's intense interest from about 15 civic groups to be involved, and we want to catch as much of that energy as early on as we can. You can't tell excited people "hey, wait a few years; we'll find something for you." That just leads to people hating you if you're successful and bailing on the idea if you're not. But the resources they bring are an amazing thing, and more than worth any challenge in having that many moving parts.

So what can you expect? I hope a pretty full-service show. You can come Wednesday to Friday and see kind of the nerdier aspects, the gallery shows and the academic conference and the night-time presentations, all up on campus. You can come Saturday and Sunday to our downtown and attend a regular expo-type small press show, 100 tables, with four panel tracks. We even have hosted parties Friday, Saturday and Sunday. We have everyone from Image Comics to Youth In Decline in the Expo room; please, oh please God buy something. Or many things.

Shows seem, at least anecdotally, to have become increasingly important to cartoonists and publishers (at least those who aren't firmly established in the general bookstore market). They certainly have become more frequent, and there are "important" shows taking place all over the country throughout the year. They are also expensive, especially if you go to a lot of them. Do you think this is a sustainable business model for small-press comics? What would be an alternative?

That's like a whole essay of answers, but in brief.

I think you're right in that we've crossed a line into there being some observable effects of so many festivals and shows. People no longer go to all of them, that's basically impossible, most people are cutting back, and even some small-press attendees are waving off shows that don't make them a special guest, or that aren't really close, or that aren't a guaranteed potential money-maker.

Do I think it's a sustainable business model? No. Was it ever? Even compared to all the other shitty business models? Maybe, with a bunch of qualifications. If it ever was, it was just barely, and it was like — like most things in comics — to the benefit of a select few. There are people that can clear after expenses a few grand, which is probably more than they're getting from any other single source. Of course there are social advantages and even spiritual advantages to connecting with people that actually read your work, or that know what you're going through, that people will frequently do them despite knowing they might not be one of those that makes money.

The assumption I'm going on for the future is that people will do their locals, will do the shows that invite them in, and then will fill out the rest of the festivals they can do, perhaps up to four or five, with one or two shows with which they have a track record of good experiences. You'll also see things like publishers explicitly supporting talent but not coming to shows themselves, and more people attending shows but only if a bunch of their friends do. I think you'll also see more and more honoraria, and things like that. We are looking at ways in our development to one day perhaps have free tables for everyone accepted. That's a long way off, and maybe not possible, though.

How do you see CXC compared to the other, more established conventions?

Catching up, mostly. There are a lot of great shows out there. That's not me being nice, that's me being jealous. A lot of the great shows benefit from being established, and have great, recurring, buying audiences as a result. At a certain point, you just need reps.

Conceptually, I hope that we're just different enough that we become a unique thing for our guests and our audience, but still with enough broad appeal that sets of those at the show professional and at the show as a reader and fan will both include a lot of people.

The Billy and CCAD and other institutions are a big distinction. If most conventions are like tent revivals that pull up and leave when the weekend is over, we're a series of churches — in the Billy's case a cathedral — and we're still here that next Monday. I think that provides a different feel even above and beyond what those institutions offer during the four-day weekend. We have great venues: we're putting Seth and Ben Katchor in the Columbus Museum of Art this year, followed by Ronald Wimberly, who has an exhibit up over there as the Thurber House Graphic Novelist residency winner this year. The Thurber House is another one of those great institutions here.

We have a broader mandate than most shows. We'll always have an animator. This year, we have two: Mark Osborne is showing a 3D version of his The Little Prince and the great John Canemaker is speaking on Winsor McCay at the same time there's a McCay exhibit across the quad at the Billy. We do have a strong strip and a strong editorial cartooning presence. A diversity-driven Expo, SOL-CON, will have events up on campus on our Friday and its artists will exhibit with us Saturday and Sunday.

We have a strong professional development track, although I think most shows are expanding into this area. This year we have about 16 hours of programming aimed in that direction, and a few surprises. We will give out another significant cash prize to an Emerging Talent on the show floor.

We also really want to show off Columbus as a place we hope cartoonists will feel at home. We want people to come live here: it's cheap, it's a great city in which to be an artist, we're close to everything east of the Mississippi and we have things like the Billy and the new comics major at CCAD. If you don't actually live here we want you to feel like you have a second home here.

What is the best non-CXC show you've ever been to?

My first San Diego was pretty awesome. I got to talk to Jeff Smith and Sergio on the porch of the Hyatt until late in the morning, there was a ridiculous Fantagraphics party, and I got to moderate the panel where everyone yelled at Larry Marder for Image going to Diamond. I'm one of the few people that still enjoys a good San Diego. I also still have a fondness for the Chicago shows I went to when I was a kid. We'd one-day it and just spend as much money as we had on all the stuff we couldn't find in Indiana, like American Splendor.

My favorite individual iteration of a show was the 2012 SPX, which was I thought was a tremendously sweet show, with a lof of people I care about in attendance.

I still feel the gold standard for a festival-style show is TCAF, though, in terms of the guest list and expo and reach and quality of the show.

How are you feeling, health-wise? Are things better after your scare a few years back?

I'm super-fat right now, but I feel great, thanks for asking. I got sick again in March. The wound that almost killed me in 2011 was conspiring to fill my lungs with clotting, and it got to the point that I went the first two months of this year severely oxygen-deprived. I was hallucinating and having severe confusion. The nerdiest part about that was that my hallucinations were like the Thurber drawing in that one Thurber-based movie: like cartoons dancing around on blank walls.

It wasn't until my physical capacity diminished to the point I couldn't walk across the room without being exhausted that I went to the hospital, though. I thought I was mentally fine except the hallucinations, which I just figured was a long-overdue psychotic break.

They zapped me with drugs and I've felt better than I have in years. I'm really lucky. We've lost a lot of great people in comics over the last few years. My friend and one-time Seattle roommate Jess Johnson died this year, for example. I still think about Kim and Dylan Williams. I was very fond of Darwyn Cooke and I think the whole field is like 3 percent less joyful and fun and hilarious for that guy not being in the room. It doesn't get any better from here, either. I'm grateful and lucky.

The long-gestating book, We Told You So, is finally coming to print more than a decade after you began it. Obviously the Harlan Ellison lawsuit had something to do with that. Are you able to talk about that situation at all? And were there any other factors behind the book's delay?

I wasn't part of the lawsuit, so I suppose I can say whatever I want.

Me sucking would be the primary cause of the book not coming out. I was originally contracted for 30,000 words, which in the writing of it — well, the first chapter was about 30,000 words. The Ellison lawsuit killed any momentum and like the Fleisher lawsuit put a strain — much less of one — on my relationship with Fantagraphics. I think that's just natural. That's a tough journey to take. Like I said, I wasn't even included in the lawsuit despite writing one book in question and editing the other. It was pretty goddamn weird.

Fantagraphics really wanted the book to come out. We had some strong disagreement as to how that would happen. Eventually, looking at my choices, I remembered talking to Kim Thompson's parents back in 2006. They passed away soon after Kim did in 2013; they are no longer with us. I remember his Mom told me something straight-up about how happy she was that they got to talk about Kim. And if I had worked against the book finally being published, my best-case scenario — my best outcome! — was that she wouldn't get to talk about her son on the record. So I reached out to Eric and Gary to change some things about the original contract which reflected our new situation and let go of my giant stupid ego.

You weren't able to finish the book by yourself. How is the final product different from what you might have put together alone? Did you ever consider putting together the book in a different form, i.e., not an oral history?

It's not exactly the book I would have written, not totally, but I'm proud of my work in there and I think Mike Dean did some heroic work in matching some of the later chapters he worked on to what we did with the earlier ones. I recommend it. Please buy it. I had a 37-email argument with Eric Reynolds about Jeremy Eaton's ponytail for a picture caption and I don't want to have wasted that time.

How would it have been different? I think I would have concentrated on some different issues. Like I'm fascinated by the falling out that a lot of Gary and Kim's same-age peers had with the Journal in the early '90s, and I think I would have covered that more. I'm more interested than the book ended up being interested on the way that Fantagraphics has shaped the publishers that come after. I think there a couple of people I would have focused on more, like Dirk Deppey. I think you can probably detect some shifts in tone if you read the work yourself. I think I would have hit on Gary becoming a father and Kim becoming a husband as key personal moments more thoroughly. Maybe. It's hard to say!

I always wanted it to be an oral history. I like oral histories, I think the wider range of personalities involved with Fantagraphics is the story, and I think it pays homage to maybe the first great distinguishing element of the company: Gary's interviews in the Journal.

I'll tell you how long ago 2005 was, Tim. At the time I did the pitch, I sort of had to explain what an oral history looked like, and there weren't a lot of book-length ones. I used the Terry Pluto book, Loose Balls, on the ABA and actually brought it into the Fantagraphics office. Now there are specific episodes of Blossom that have received the oral-history treatment. I can tell from reading Mike's chapters that this had an effect on how those chapters came together — like people know that oral histories have overlapping narratives time-wise, you might introduce someone not when they first show up, but when they become important. That was a hard sell in 2005-2006, lot of arguments there.

How many people did you interview for the book? Was there anyone you wanted to talk to but couldn't? Who gave you the best stories?

I don't know, I'd have to count. Because my chapters literally involved fewer people, I bet Mike ended up talking to more people than me. But there were plenty. I wish Mark Waid had spoken to me back in 2006 when he declined to, because his was a colorful personality so he's in the book but his perspective on himself and those times isn't in the book. I wish Gil Kane had lived long enough to talk about his perspective on he and Gary's friendship.

The best stories? That's probably not for me to say because I knew almost all of the stories going in. It was more about tone and insight for me. Reading it, I thought early '90s employee Helena Harvilicz came across really well; that was an interview she did later, not with me, I don't think. I really liked the diary entries that Rebecca Bowen — she worked there in the mid-1990s — allowed us to use.

You used to work at Fantagraphics, and obviously your tenure editing TCJ was an important and popular one. What was Fantagraphics like when you were there, and how has it changed since you left?

That's nice of you to say, but I'm not sure my tenure was remarkable unless you're a typo-fetishist. I got lucky in that I had a lot of really good interview subjects fall into our range when I was there: Mignola, Mazzucchelli, Seth, Schulz, Ware. Also I was lucky enough to find Bart, whose "Euro-Comics for Beginners" column was one of the most important columns. I trust my sensibility about comics, although I'm pretty doubtful of my skills as an editor, magazine or otherwise.

I was probably one of the last employees who went to work for Fantagraphics in part because I wanted to be with people who got my jokes. I was pre-Internet, a solitary comics reader, and the thought of working on a magazine I enjoyed about a subject I loved was way more appealing than watching people sniff underwear at a Home Shopping Network warehouse. I was Gary's fifth choice.

It was really young, Tim. I showed up for work about two months after Kurt Cobain killed himself — not related — so the whole city still felt young, but not excitingly so, maybe. But the office, Jesus. Gary and Kim were the oldest and they were like 37 and 39. Conrad Groth was a baby. The vast majority of us were 26 or younger. It was a lot rattier, with loud music and a lot of smoking on both porches. We did not have full computer coverage — Roberta Gregory used to come in to cut Rubylith and what is now the marketing room was half Kim's office and half the stat camera room.

The general sociability of the employees is way, way, way up now as is their age. Eric now would have been the oldest employee then by almost a decade. And we were all dirt poor — that maybe is the same — my initial salary was huge for there, $15K. A lot of young people needed jobs, though, and it was a cool place to work. The staff photos from my era look like the line outside a methadone clinic.

How did—and how do—you get along with Gary?

Gary and I yelled at each other a lot, especially early on. I was scared to death, I am not high-functioning then or now, and I lied to get out of things. I was a sharp contrast to Scott Nybakken, who is almost a muppet — one of the nice ones, like Scooter. I still have this strong visual of Eric sitting in his chair in Gary's office, legs held to his chest, watching Gary and I trade insults. There's some of that in the book. If anyone out there ever sees me and wants to know what it was like to work at Fantagraphics in the 1990s, ask me to tell you the trash can story, which I will never write down. I spent my 26th birthday hiding in the library, crying, thinking I was going to be fired.

I love and admire Gary. I did so back then, too. We look at things very differently, and we both could probably tick off three to five things about which we disagree very, very strongly. But he's also been a very good friend when I've needed one, above and beyond. He was a tough boss but he was good in a lot of ways, too, like letting me do stuff I wanted to do and backing me up publicly when things misfired, like the time TCJ eschewed a hit list for a "shit list." I owe him the general shape of my life if not more than that, really.

The unlikely nature of the accomplishment that is Fantagraphics always floors me when I spend any time thinking about it. Gary and Mike and Kim were kids that spent a lot of time in their bedrooms. I think of teenaged Gary counting letters so that he could typeset his zine with a typewriter. I think of him talking to Harlan, the interview, and kind of wanting out loud there to be literary graphic novels without even being able to come up with what that would look like. I think of him hammering his best friend Gil Kane about the nature of making art and being brave in those choices. My life is richer for his specific achievements above and beyond my personal involvement. And Gary and Kim sticking to their guns through thick and thin just kills me. Hell, Gary and Mike started the company when comics was at perhaps its most unremarkable and most unlovable, and all of those involved, Preston White and Kim and so on, they all lived hand to mouth in order to do this. And it lasted forever. Tim, in the '90s we had office meetings where they asked if anyone could skip a paycheck. They white-knuckled it for so many years, my head would have exploded in about 1992.

One of the main figures of the book, Kim Thompson, is unfortunately no longer with us. What was it like putting together the chapter on his death? What would he have thought of the book?

Kim was really supportive of the book in its earliest forms, and was enthusiastic about what it might become. I hope he would have liked the final result. He hated me assuming his opinion in life, so I'm going to respect that in death. Kim would be the worst ghost to have haunt you because he would do it 7 days a week, 16 hours a day. And he would speak in different ghost languages.

The Kim's death chapter was the only one of the later chapters I did. What struck me about Kim's death beyonds its suddenness was how quickly he shut things down. He really limited who he saw, what media he consumed, what conversations he had. So I wanted the chapter to reflect that, with a lot fewer voices, even if that wasn't made explicit.

I also wanted to round off the book's portrayal of Kim, and what a unique personality he was, and to underline how proud he was of his company and its legacy. He was always Fantagraphics' truest believer.

What are your favorite periods and/or anecdotes from the book?

I liked all the early stuff because I could compare my perception of the company with the reality of it a bit, and that's always amusing. Fantagraphics was not really a clubhouse by the time I was there, so the thought of all those guys living in the same space in Connecticut and working like mad in between sleeping and maybe leaving the house for a little social activity fascinates me, too.

Fantagraphics seems inevitable now, but it super-wasn't. And in an era in comics where we have a lot of 40-year-old rookies, it's amazing to think of a time when a couple of guys in their late twenties could carve out a major industry role for themselves. So anything that's a reminder of that, I love.

My favorite story is probably about them driving to California and totally not being up to this task and one specific line from Kim during that whole ordeal. I'm forgetting a bunch of stuff, though.

What do you think is the book's final value?

I hope people are entertained by it. I hope they get the value of commitment out of it, how they stayed the course. That's never been a common thing but is super-rare now. I'm afraid in this era where we win argument some of the warts-and-all stuff may just be seen as "they're proud of being dumbass jerks" instead of the humanizing quality I want it to be. I don't want this to be a branding exercise. I don't see it as a final or summary statement on those people, that company, its value.

I guess I hope people better appreciate the unlikely and immense achievement that company is, at a time when most of the principals are still alive to be appreciated.

How do you feel about the Comics Reporter these days? Do you plan to release any more issues of The Comics Report?

I think CR has been terrible for about two years and I'm way behind on Comics Report. I vow to catch up, and in the case of the site do a better job, but that vow doesn't mean a goddamn thing until I do it. I'm terribly sorry, and embarrassed, and I should be. But again: that's all just talk unless I can get back on track. And if I don't soon, I'll take a different approach.

The core reason I took on CXC is that I think we have a chance of making things better through that show for comics professionals and comics readers. That sounds dumb, but I really believe that. I wouldn't have taken it on if I thought it would screw up my other work, but all I can do now is work out of it until I'm either back on track or surrender.

The Comics Report was intended to be a monthly publication offered as an incentive to backers of your Patreon fundraiser. [In the interests of disclosure, I should say that I am a backer of your Patreon myself.] Have any Patreon sponsors asked for their money back?

Sure. And they should have. And I'll do my best to make it up to them, too. Most people have been positive and supportive, and I can't say how much I appreciate that. I don't take any of this lightly. I accept full responsibility. I demand better of myself and we should all demand better of non-creatives in comics. This is what failure looks like.

How has the evolution of the comics industry differed from how you envisioned it back when you first started covering the field? What would you change if you could?

Holy shit, what a question.

Here's what popped into my head.

I'm an old man who likes to walk to the bank to deposit checks and pay my bills in person. This comes from my Dad, who was a Great Son of his city and a civic enthusiast.

What I see as the biggest difference in comics between 1994 and now is that we've dismantled a lot of the industry parts of it. My main interaction time-wise with comics in 1994 was going to the store and reading them. My main interaction now is interacting with comics people on Twitter. That's not always a bad thing to give up on aspects of industry, because industries can be unfair and exploitative, and comics' version was both.

Still, without some sort of structure… well, right now it just feels like we're making comics and then throwing them into the ocean. I don't even know when people I like are going to have comics out, and this is my job. I can't imagine how soul-killing it is to work on something for two years, have it out, get one review and maybe a convention out of it, and then never hear anyone talk about what you did ever again. I see it as a systemic failure: we've had all the things happen to most media businesses decentralizing and spreading out cost, and ours was never that strong to begin with.

My main goal in my professional life, and I would suggest all of our main goals might include this because the "comics for everyone" fight has concluded on some fronts and still advances on others, is to make things better for those involved: yes, the readers, but primarily the makers of this material. It sickens me with all of the money made overall that we're still in a situation where so many creators have to harm their lives in order to make art in a medium we love. Even the traditional ways people can have happy and successful lives making comics could use some bolstering.

So I'm hoping for a full-bore assault on this stuff. Greater honesty dialogue about money and reward — as soon as we started asking the kids to go to school, this became compulsory. More savage criticism of ethical shortcomings in contracts and pay. Greater participation in a wider arts world of grants, monies, and support from institutions. Paying people for every possible thing that we can, deciding not to do some things that don't or can't pay even if we really want to, and making people justify not paying someone something rather than the other way around. And I want to spend as much time as I have left, whatever that is, focusing on actually changing these things rather than winning the argument of them.

This will make for some brutal questions, and self-reflective moments just as tough. And then the real work begins. What I hope, though, is that we can at least be oriented in a way where harm seems less likely.

Either that or D'Arc Tangent #2.