With the sad news that Kevin O’Neill has died this month, the British comics world is once again in mourning. In recent years we have seen the passing of Garry Leach, Alan Grant, Steve Dillon, Carlos Ezquerra, Jim Baikie and Ron Smith, bringing about the dawning realization that this formative generation of creators, who so radically transformed British comics in the pages of 2000 AD, is gradually leaving us. Kevin O’Neill was there at the very formation of 2000 AD and is unquestionably one of its most important creators, dreaming up a succession of wildly inventive images that had never been seen in the medium before. He constantly evolved as an artist and unquestionably inspired future generations to go ever further out there, despite being paradoxically fresh-faced, charming and mild-mannered in person. It’s always the quiet ones...

Kevin recalled his childhood as a comic fan, writing in the SSI (Society of Strip Illustration) Journal in 1979: “From as far back as I can remember I wanted to be a comic book artist. My formative years were spent collecting and absorbing the clean linear styles of Bob Kane, Jack Cole, Ken Reid and Leo Baxendale, among others.” After a chance playground swap he was introduced to a more subversive kind of American comics in the pages of The MAD Reader, which he later regarded as his creative ground zero, along with Reid’s beautifully anarchic strips in The Beano. Science fiction was another formative influence, as he recalled in the 2021 "Kev's Own" addendum to his Cosmic Comics miscellany collection: “My love for robots began at a very early age when I saw the old Republic studio science-fiction serials at Saturday morning pictures [British slang for a cinema].... But what I really liked was Robby the Robot in Forbidden Planet and his near brother-robot in television's Lost in Space.” Fittingly, in his time at 2000 AD Kevin effectively became the comic’s official robot designer, a role he excelled at.

Kevin had initially planned to attend art school, but he was forced to find work when his father retired early. As he later recalled: “In May 1969, wearing my best clobber [clothes] I took a day off school to visit IPC. The outcome was a job as an office junior on Buster under editor Chris Lowder. After moving around a bit I eventually joined Bob Paynter’s humour department where my first job was to white out signatures.” IPC’s legendary designer Jan Shepheard told the eager 16-year old that it would take him 10 years before he would be accomplished enough to become a professional comic artist, and she was proved to be right. Comics at IPC in the early '70s were in something of a creative decline, though they could still boast some exceptional talents such as Don Lawrence, José Ortiz, Jesús Blasco, Ron Embleton, Francisco Solano López and the young José Muñoz. However, very few new talents would emerge until much later in the decade, and much of the writing was considered moribund and formulaic. Kevin’s role in the art department largely involved correcting artwork and re-formatting old strips for reprinting in numerous Annuals and Summer Specials. It would have been both enormously enlightening to see so much vintage artwork, but creatively frustrating.

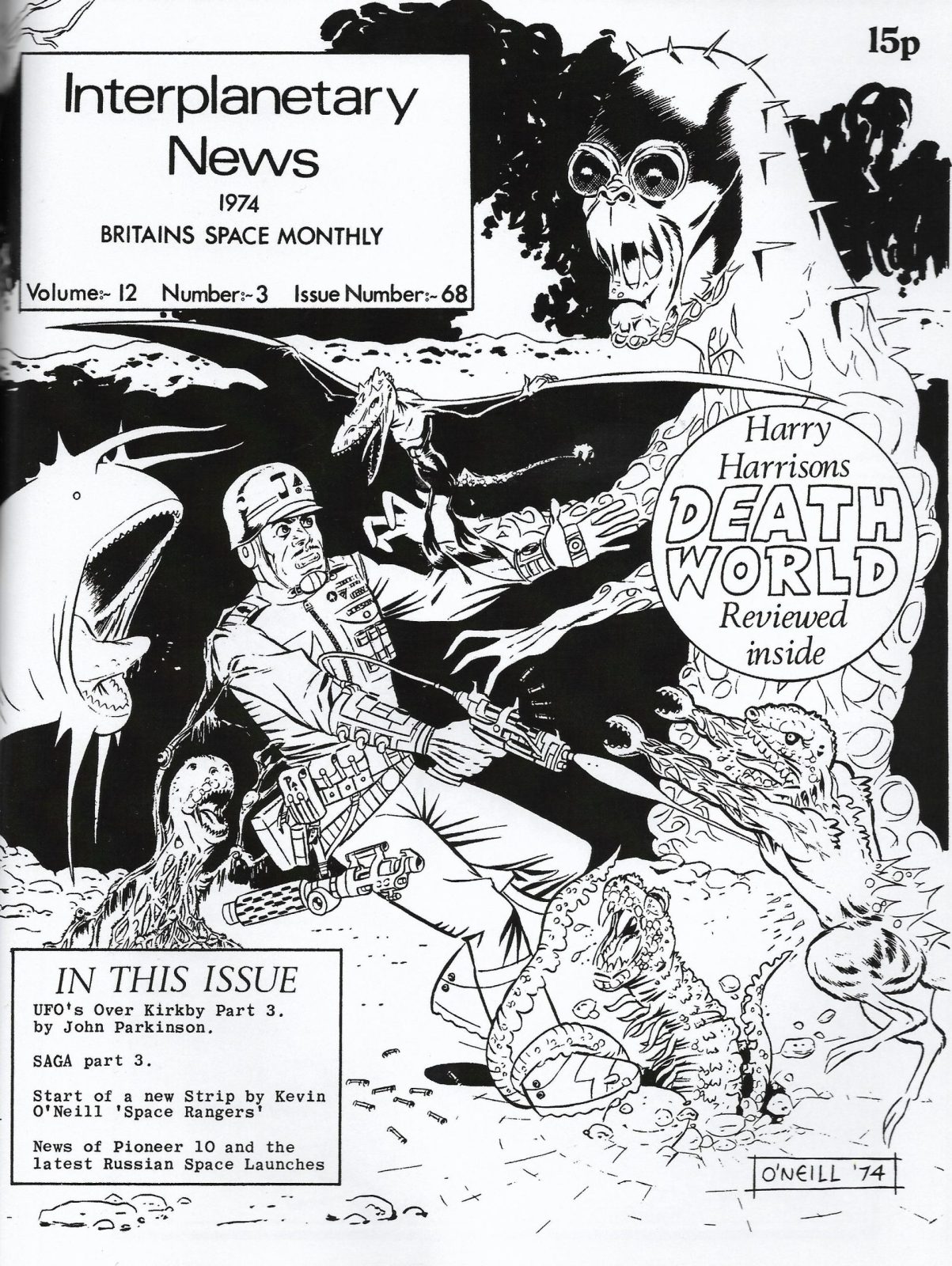

In the humor department Kevin met future comic stars Steve Moore, Dez Skinn and Steve Parkhouse (the three would later become central figures in the success of Warrior magazine), all of whom were already deeply immersed in comics fandom. Writing in 2021, Kevin recalled that “Dez sold me a copy of his Fantasy Advertiser No. 32... and over time while following FA and other fanzines I saw the early and very impressive work of both Dave Gibbons and Brian Bolland. Also in those days pros like Jim Baikie, Ron Embleton and the mighty Frank Bellamy all supported fan publishing, often contributing new artwork. Enthused by all this activity I began doing odds and ends for any fanzine that would publish my very poor, but for free artwork.” His first fan art saw print in the pages of Bibliotheca HP Lovecraft in 1971, followed by work for Fantasy Advertiser, Interplanetary News, Fantasy Unlimited and five issues of his own film and TV zine Just Imagine. By this point he had moved to the IPC coloring department working with Gina Hart, where he honed his impressive coloring skills - reflected in impressive color work in his fanzine appearances and many later professional jobs. Some of these early strips and illustrations showed a marked influence from Jack Kirby and Jim Steranko, and over the course of the decade Kevin developed a highly slick, polished inking style that could perhaps be traced back to Steranko. Though his figure work could often be somewhat stiff, his design sense was already highly developed and his innate creativity certainly compensated for these rough and ready drawing skills.

By 1973 he had tired of his work at IPC and left to go freelance, mixing production and illustration chores on Annuals with cover and strip art for poster magazines such as World of Horror, Doctor Who and Legend Horror Classics, where his art appeared in eight out of its nine issues. His final issue of Legend Horror Classics—the 9th, by which point he had become its publisher—featured a severed head cover which was so disturbing it lead to condemnation in Parliament (a foretaste of scandals to come). A debt of £300 drove him back into IPC’s art department, where he was fortuitously in the right place to join a new science fiction comic being put together by Pat Mills and Kelvin Gosnell. In 1976 Kevin published the only issue of his Mek Memoirs fanzine, which he drew in its entirety, together with scripting by Chris Lowder; this effectively became his audition for a position at the new title, which of course became 2000 AD. Kevin officially joined the staff of 2000 AD in September 1976, again working with Jan Shepheard in the art department, where he stayed for the next two years, a period which saw a radical change in the direction of British comics.

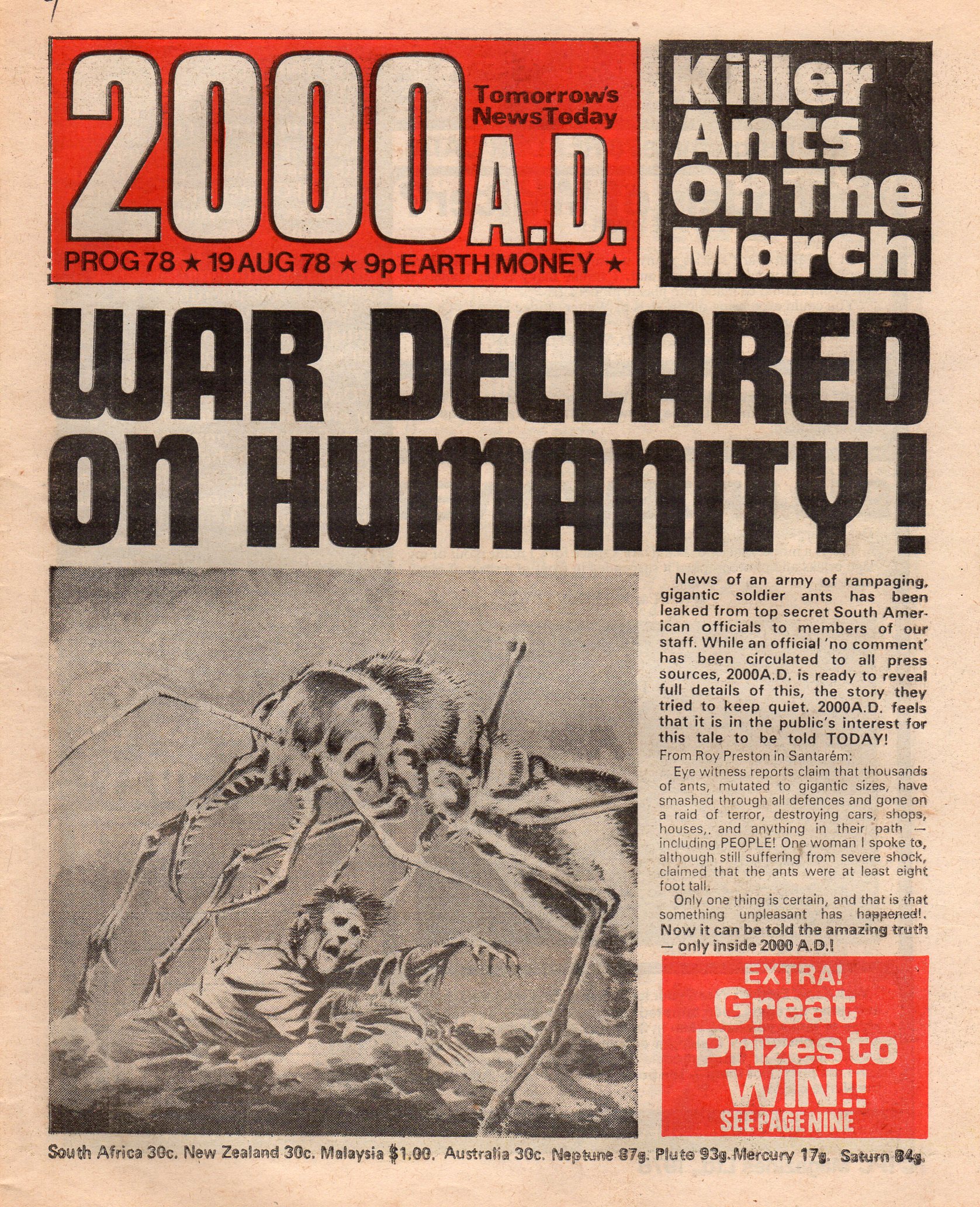

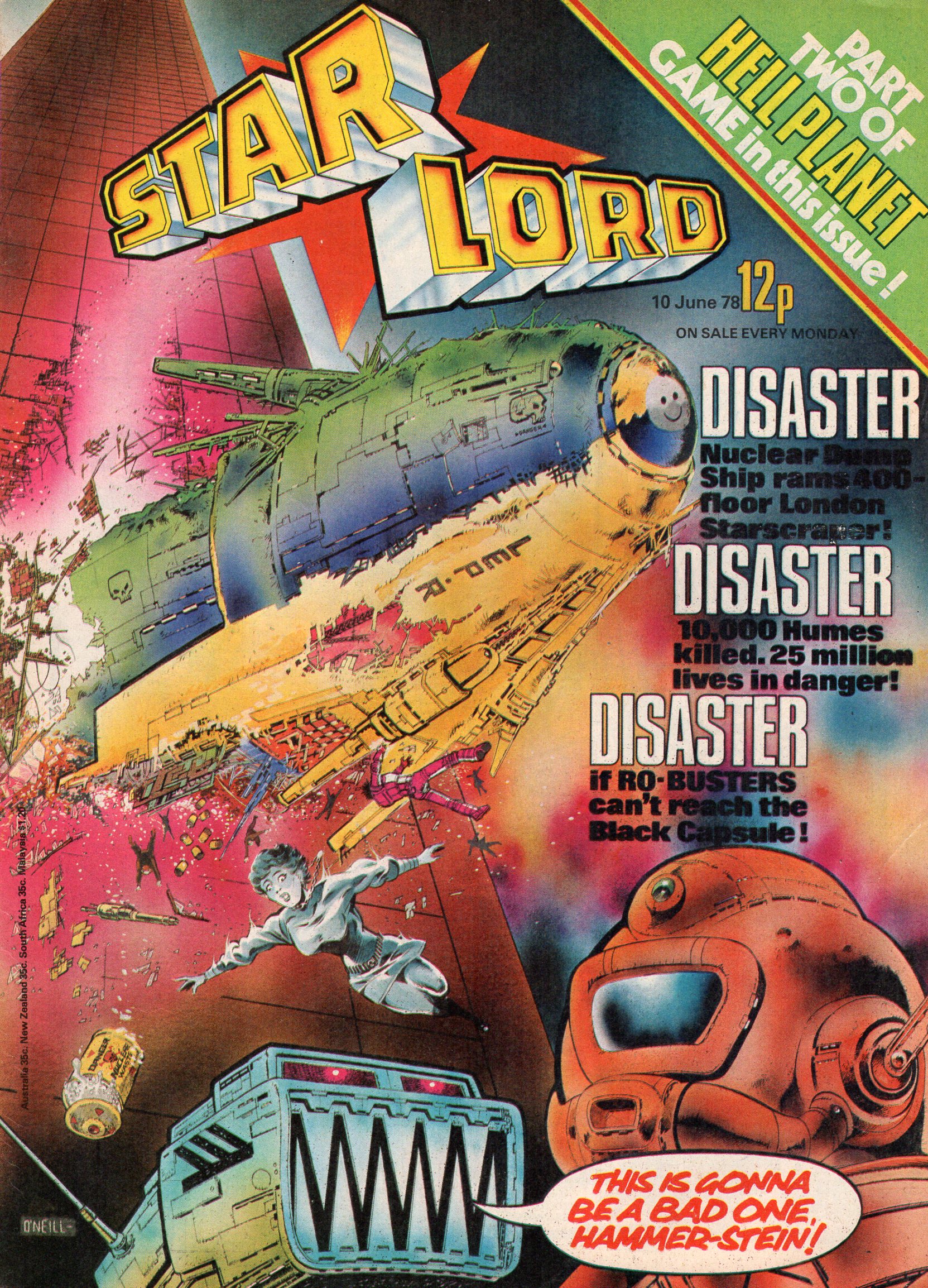

Staff at IPC were typically expected to pitch in creatively on top of their editorial duties, often contributing scripts, illustrations, covers, and even strips where the need arose, and throughout these first two years Kevin became an ever more visible presence at the comic. His first strip appeared as early as issue 4, a one-page back cover feature explaining the world of the Flesh strip, scripted by Pat Mills; the first of many collaborations between the two. Issue 24 featured his first full-length strip, which was also the first strip starring the comics’ fictional editor, Tharg the Mighty, complete with numerous comic and science fiction in-jokes. At around the same time his first Judge Dredd strip appeared, in the 1977 Summer Special, together with a gorgeously rendered, painted cover. Other early work included a pair of Tharg's Future Shocks strips in issues 28 and 36, several more covers, and the 10-part cartoon serial Bonjo from Beyond the Stars in issues 41-50. But Kevin's influence extended far beyond just strips and covers; he contributed adverts, free gift designs, story logos, and even introduced the credit boxes that finally gave the comics' creators the recognition their work deserved (seemingly without actually asking permission from IPC’s management). When a companion comic, Starlord, was developed in 1978, Kevin worked with Mills to create the immensely popular Ro-Busters strip, designing its robotic stars and hardware, though he was only actually able to draw two covers and a pin-up for the Starlord run of the feature. Other notable work in his second year at 2000 AD included some wildly imaginative Ant Wars covers and fully-painted covers for the second Summer Special and the 1979 Annual. But when Starlord was amalgamated in the pages of 2000 AD and plans were developed for a new series of Ro-Busters strips, Kevin decided to try freelancing once again and devoted himself full-time to life as a comic artist.

For Pat Mills, very much the creative force behind 2000 AD, the comic represented a break with what he saw as the traditional, conservative British comic. Mills had already found great success with two earlier comic launches: Battle Picture Weekly in 1975 and Action in 1976, though their innovations were largely felt in their punchy, violent scripts rather than their artwork. For 2000 AD he was looking for something different, a more imaginative, rebellious, anarchic approach similar to what he had found in the pages of the cutting-edge French title Métal hurlant. It took several years to build up the creative art team that propelled 2000 AD to such success and influence, and what he was looking for was more about a certain sensibility than solid drawing ability. Few of IPC's established artists had what he was seeking, so the title ended up becoming a showcase for an entirely new generation of creators. By the time Kevin became a regular at the comic in 1978, his artwork had become highly polished and attractive, while still frequently surreal, inventive and utterly bizarre. He never lost the manic energy he inherited from Baxendale and Reid, and in Mills he had a writing partner who would continually push him to ever greater heights of demented creativity.

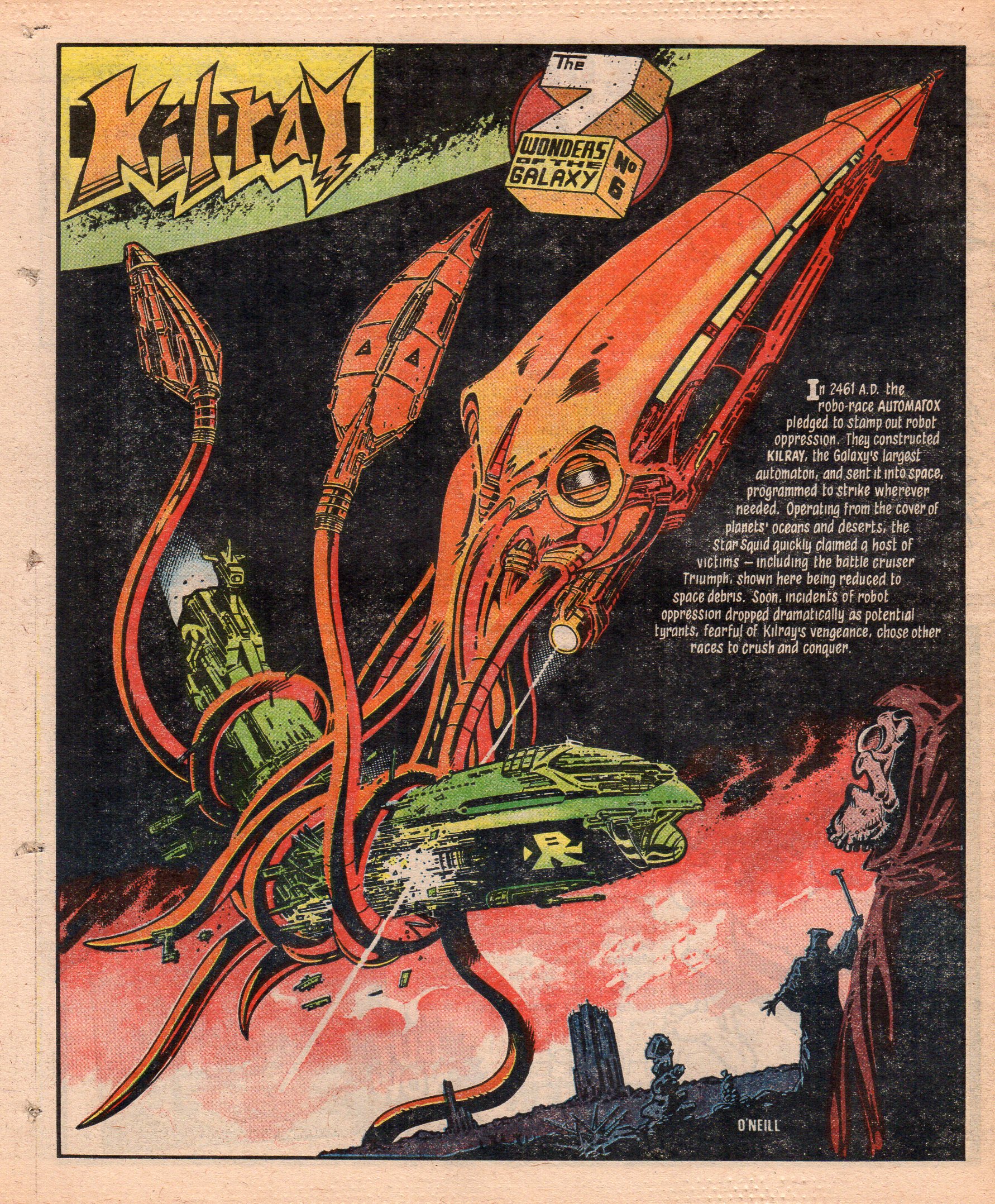

In his first few years as a freelancer from ’78 to ’80, Kevin produced six episodes of Ro-Busters, two of its follow-up series, ABC Warriors, and numerous covers. In all he would craft 37 covers for the comic before moving over to the US market. His love of humor never left him, and he drew 9 episodes of the jokey Captain Klep strip for Tornado (another action-oriented IPC weekly) in 1979, and 20 installments of the Flash Gordon spoof Dash Decent for 2000 AD the following year. Perhaps the first evidence of the sheer breadth of his imagination came with a series of glorious science fiction pin-ups in 1980: "The 7 Wonders of the Galaxy" (in issues 162 to 168), which had the monumentality of Jack Kirby or Philippe Druillet and hinted at great things to come. Kevin had been arguing that 2000 AD's artists should be able to own the copyright to their own work, and for the "7 Wonders" series IPC indeed allowed him to keep full ownership, though for only 25% of his regular page rate (perhaps unsurprisingly, none of the other artists followed his lead). Another memorable feature from this period was a short strip called Shok!, written by 2000 AD editor Steve MacManus for the first Judge Dredd Annual in 1980. A decade later it inspired Richard Stanley’s cult film Hardware, without permission, resulting in a court case which the publisher (by that point renamed Fleetway, for the second time) ultimately won.

1980 proved to be a pivotal year for Kevin, when one of his most important strips emerged as a result of plans he and Mills developed for an ongoing series of one-off science fiction strips, loosely inspired by song titles, under the banner "Comic Rock". The first episode in issue 167, "Terror Tube", introduced the tyrannical Torquemada and his arch foe Nemesis (or at least his spaceship, the Blitzspear), in a story that demanded a follow-up. The next two installments in issues 178 and 179 proved so popular that a series was commissioned, though after two proto-steampunk episodes were drawn Mills decided to change direction completely. He felt he needed to explore the background of this new Nemesis character, who had still not actually been seen in the strip, so he switched the strip’s tone away from straight science fiction to a sort of darkly humorous, mystical, alien sword-and-sorcery tale. This new direction gave Kevin a free rein to conjure up hideous alien creatures, bizarrely organic futuristic civilizations and exciting action scenes that captivated the readers. Add to the mix Mills’ hatred of the Catholic Church (born of years in Catholic schools) and innate anti-authoritarianism, and Nemesis the Warlock was a richly entertaining concoction and an unlikely success which established Kevin as a star.

Book One of Nemesis was serialized in 2000 AD issues 222 to 244 in 1981, while Book Two was drawn by Jesus Redondo to allow Kevin to concentrate on the panoramic wonder of Book Three, which saw print in issues 335 to 349 in 1983. For many, this series remains Kevin’s masterpiece, with his work becoming ever more imaginative and his style pushed to ever greater levels of intricate detail and demented invention. Where his previous strips had been polished and controlled, by his second Nemesis series his art had become noticeably grittier, with the earlier brush work replaced by hard-edged pen lines. In the early years of the '80s there was this sense that 2000 AD's two great maverick artists—Mike McMahon and Kevin O’Neill—were spurring each other on to ever more abstracted, gritty, imaginative work, to be reflected in their masterpieces; McMahon's run on Sláine and Book Three of Nemesis ran concurrently in 2000 AD in late 1983. An abandoned follow-up storyline eventually appeared in 1984-85 as Book Four, with Kevin's initial two episodes continued by Bryan Talbot.

In between Kevin’s two full Nemesis series, a meeting of the SSI took place in 1982 which was to have far-ranging consequences for British comics. The meeting featured a presentation by Joe Orlando and Dick Giordano of DC Comics, looking to recruit British talent for new projects in America, with the promise of better pay, ownership of their work and royalties. Over time, almost all the creators present would go on to work in the US, including Kevin, though at that point he still had more work to do with Nemesis. 2000 AD's popularity resulted in a series of beautifully presented reprint books published by the newly-formed Titan Books, all of which featured new painted covers and some new interior artwork by the series’ original artists. In 1983 and ‘84, Kevin painted six new covers and numerous illustrations, along with some new strips, for the various reprint books, with his covers in particular still standing as some of the best work of his career. Titan then decided to branch out into the American market under the Eagle Comics imprint, repackaging the cream of 2000 AD's strips in comic book format reprints. For Eagle’s second series (after Judge Dredd), Kevin resized, colored and added new artwork for a seven-issue Nemesis the Warlock comic book that appeared in 1984 and '85, drawing on his years of production work at IPC. Again, the new cover art was sublime and bizarre in equal measure in what was, for most American readers, their first exposure to his work. Away from his main two storylines, new Nemesis strips by Kevin appeared in the 1983, 1984 and 1988 2000 AD Annuals, and 2000 AD issue 430 in 1985, followed by a Nemesis game in Dice Man #1 the following year, and a short series called "Torquemada the God", which was serialized in issues 520-524 of 2000 AD in 1987. After 1985, most of Kevin's focus would be on American comics, but he periodically returned to British comics if the project took his fancy, with still a few more Nemesis strips yet to come.

I was one of the second generation of 2000 AD artists who came into the comic as our predecessors moved on to the American market - with my first series, in fact, being Book Eight of Nemesis the Warlock in 1988. Later in the '90s, I too started working for DC Comics, and it was fascinating to hear my editors talk about their perception of British artists. While they universally admired their drawing ability, it seems the consensus was that their artwork was a little weird, or in Kevin’s case, extremely weird! Much as DC no doubt appreciated his unique talents, there must have been some initial doubts as to how he might fit in at the company. Indeed. What could you give someone whose forte was drawing hideous aliens? Luckily for Kevin, DC actually had a few series that required just that particular skill: "Green Lantern Corps", running as a back-up in the regular Green Lantern comic, and the deluxe series The Omega Men. Starting in late 1984, Kevin went on to draw five Green Lantern Corps strips (in Green Lantern 182, 183, 189, 190 and The Green Lantern Corps Annual 2) and three Omega Men strips (in 24, 26 and Annual 2). The strip in Omega Men issue 26 was written by Alan Moore; published in May of 1985, it was their first collaboration, while their second strip together, "Tygers", eventually saw print in late 1986 in The Green Lantern Corps Annual after so horrifying the Comics Code Authority that they refused to pass it. Famously, it was not just the content of the strip that appalled them, but Kevin’s artwork itself, which evidently was so inherently objectionable that he was effectively banned for life. Naturally, he wore this as a badge of honor, and the Annual was published without the Code stamp on its cover.

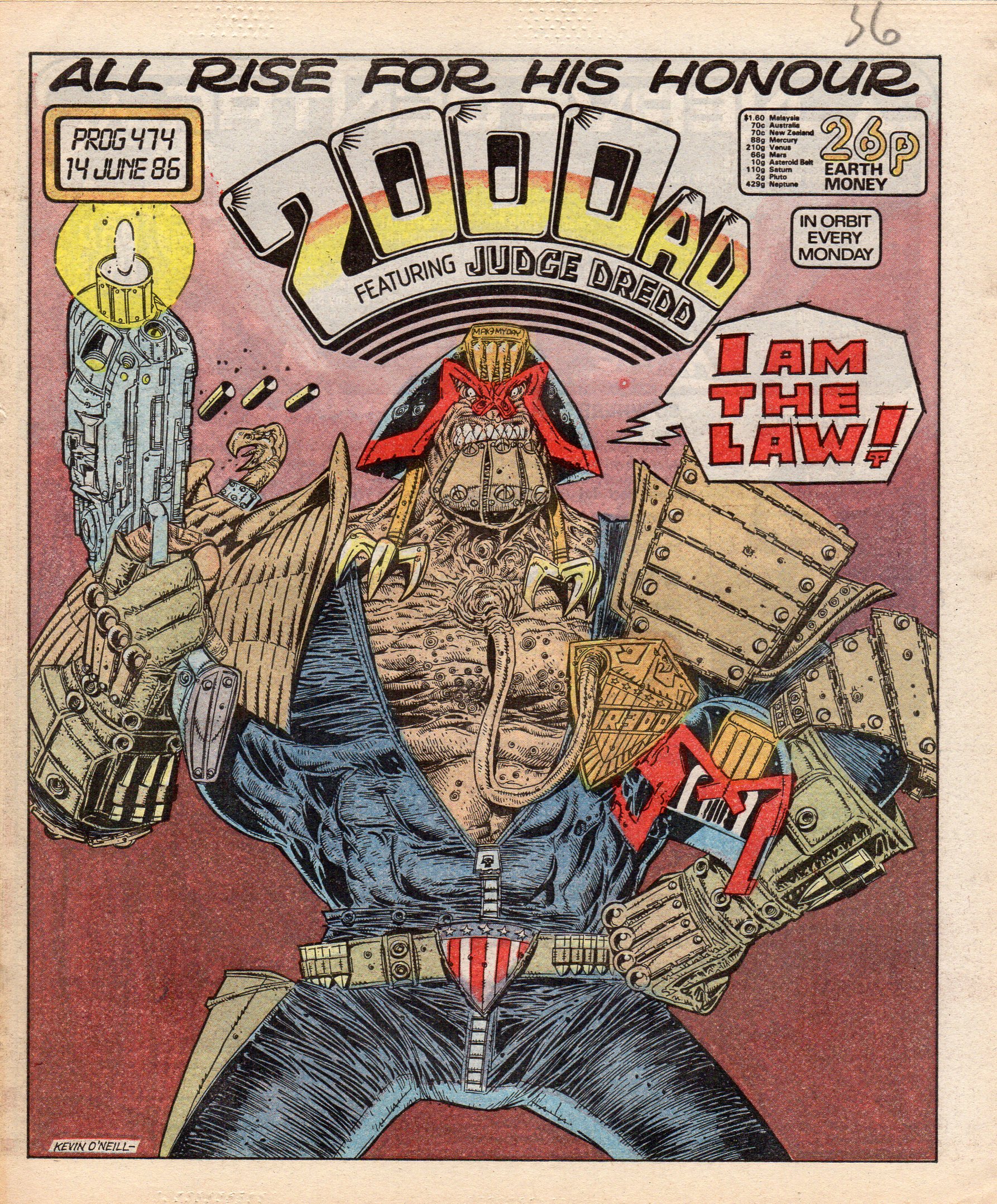

1986 mixed DC and 2000 AD commissions: Metalzoic for DC, and a couple of Judge Dredd strips for 2000 AD. Metalzoic, written by Pat Mills, was a science fiction strip featuring robotic versions of Ice Age animals which showcased Kevin’s knack for crunching action, gorgeous coloring and masterful robot designs. In an ironic twist, Metalzoic, which the creators owned, was licensed to 2000 AD, which serialized it in black and white only a month or so after its American premiere as a color graphic novel, complete with four new covers. Kevin’s two Dredd strips—"The Law According to Dredd" (in issues 474 and 475) and "Varks" in issue 503—both featured some of the most hideously drawn mutations in comic history, something at which Kevin excelled, and both are very fondly remembered by fans to this day. (Had they ever seen the strips, the good people at America's Comics Code Authority would no doubt have spontaneously combusted in horror.)

Mutants and robots aside, what Kevin and Pat needed to really make it in America was a comic series with mass appeal, or at least as close to mass appeal as their naturally twisted inclinations would allow, and that meant superheroes. Unfortunately, Mills hated superheroes, but working closely together the pair came up with the perfect premise: a superhero who hunts other superheroes, allowing the writer to vent his limitless bile at the genre in ever increasingly violent and transgressive ways. Kevin suggested the name "Marshal Law" and created the character's masked appearance, along with providing fully-painted artwork. Marshal Law first appeared as a six-issue miniseries from Marvel’s Epic imprint, running from 1987 to 1989, followed by the one-shot Marshal Law Takes Manhattan. In what was now becoming a pattern, the separation house doing production work on the second issue were so appalled at its unrelenting violence that they issued Marvel the ultimatum that unless future issues were toned down they would refuse to work on them. At the time, Marshal Law was one of a number of prestige projects such as Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen and Batman: The Killing Joke, which were hailed as pushing the comic medium in a more challenging, mature direction, though today Marshal Law is not widely mentioned in such company. Instead, it can perhaps more closely be seen as a forerunner of the more outré superhero strips like Garth Ennis’ The Boys, which shares a similar taste in outrage and extremes. While plans were being formalized for future Marshal Law stories, Kevin found work in Epic’s "Shadowline Saga" superhero comics, contributing four covers to its various titles and two "Doctor Zero" strips in the first two issues of Critical Mass. The story in issue one was inked by Bill Sienkiewicz, possibly the first time Kevin was ever inked by anybody else, and the unlikely pairing worked surprisingly well, with the inks adding a realistic, illustrative touch to Kevin’s more stylized pencils.

When Marshal Law next appeared, it was as a one-shot title: Kingdom of the Blind, published in 1990 in the UK by the newly formed Apocalypse Ltd, closely followed by further episodes in Toxic! magazine. Since the formation of 2000 AD, its creative workforce had thrived and reveled in the relative creative freedom they were offered in its pages, while growing increasingly resentful at not owning their creations and the lack of royalties. Toxic! was conceived as a creator-owned answer to 2000 AD, and with work by Mike McMahon, John Wagner and Alan Grant, alongside Pat and Kevin, the comic featured many of 2000 AD's key creative forces. I can vividly remember conversations with Alan Grant at the time (while we were working together at 2000 AD), and he was convinced that Toxic! was going to be a massive success. However, after problems with payments, scheduling, and strips of varying quality, it was cancelled after 31 weekly issues, which ran from March through October in 1991. New Marshal Law strips only appeared in the first eight issues of Toxic!, with its episodes belatedly gaining a wider audience when they were reprinted in the 1993 Dark Horse collection Blood Sweat and Fears. One of Toxic!'s selling points to its creators was the lack of editorial control, but in retrospect many of the features might have benefitted from some editorial restraint and judgement.

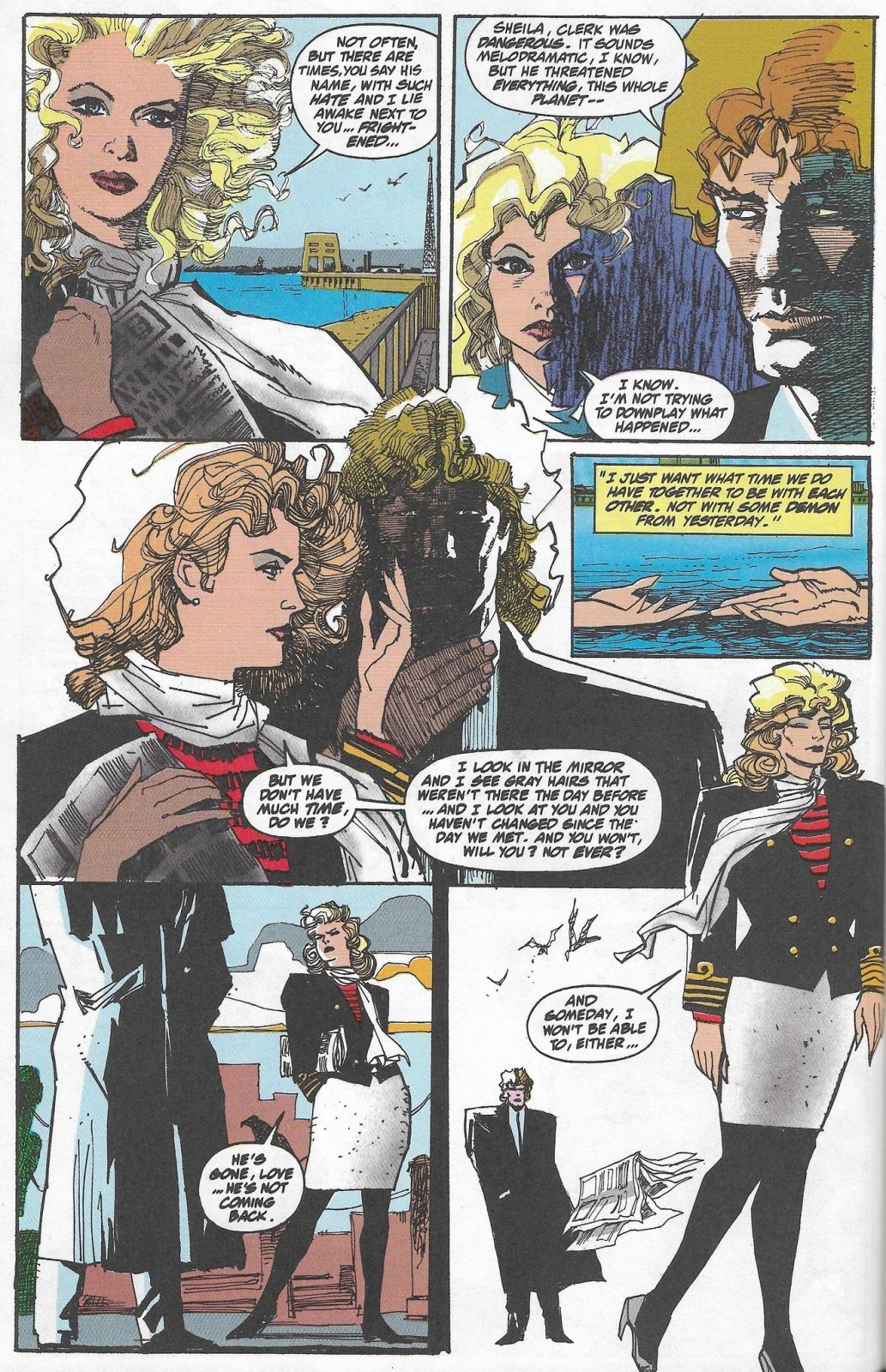

For the rest of the '90s, Kevin swung back and forth between further Marshal Law stories and high-profile assignments at DC. In addition to two new strips for Dark Horse (Super Babylon and Secret Tribunal), Marshal Law became something of a team-up specialist, pairing off against Clive Barker's Pinhead (at Epic), the Savage Dragon (at Image) and the Mask (at Dark Horse), remaining in print through numerous international collections. At DC, Kevin excelled at drawing his own, typically grotesque, twisted interpretation of Bat-Mite (in Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight issue 38 and the 1995 one-shot Mitefall), and a couple of Lobo strips, all written by Alan Grant, along with a wonderful Bizarro tale in the 1998 Adventure Comics 80-Page Giant, written by Tom Peyer. Other assignments from the period included the violent Death Race 2020 with Mills & Tony Skinner, from Roger Corman’s Cosmic Comics, and some surprising appearances in Penthouse Comix. For someone with a style as unconventional and controversial as Kevin, he had negotiated a decade and a half in American comics with considerable success. There was one more iconic series still to come.

Kevin had last worked with Alan Moore back in 1986, and was reunited with him in 1999 on The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, one of several releases under Moore’s America’s Best Comics imprint. The concept of a designated Alan Moore comic line came from Jim Lee at his Image Comics label, Wildstorm, though by the time the first issue saw print it was actually published by DC, with Lee having sold Wildstorm to DC in the interim. Despite Moore’s stormy relationship with DC, the writer felt he still had things to say in comics, and wanted to fulfill his commitments to his collaborators, so the line went on as planned. League became a standout success for the imprint, with an initial six-issue run in 1999-2000 followed by second miniseries in 2002-03, and the Black Dossier hardcover one-shot in 2007. The strip’s premise imagined a team-up of great fictional icons: Mr. Hyde, the Invisible Man, Captain Nemo, Mina Harker and Allan Quatermain - effectively, in Moore’s words, the Justice League of Victorian England. With Moore’s lovingly-crafted, endlessly inventive writing, and Kevin’s intense artwork, it was a considerable hit, even spawning a film from 20th Century Fox in 2003 from director Stephen Norrington. (Unfortunately, the film was not well-received, and then in turn inspired a plagiarism lawsuit which soured relations between Moore and DC irrevocably when the writer felt he was not given enough support by the publisher.)

In the wake of this fallout, the third League series, Century (issued as three standalone one-shots) was co-published beginning in 2009 by two independent houses: Top Shelf in the US, and Knockabout in the UK. The series continued across three Nemo hardcover originals from 2013 through 2015, and finally the six-issue The Tempest series in 2018-19. These later stories opened up the series to different timelines, genres, and characters, most notably Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. Throughout the series, Kevin mixed intensely focused, densely detailed sequences with cinematic splashes and amazing flights of fancy. There is a wit and depth to the strip, with its dense cultural and pop-cultural references, which needed an artist of Kevin’s endlessly inventive vision to bring to life, and it is impossible to imagine anyone else drawing it.

In between the last League series, Kevin collaborated with Moore on strips for the Avatar Press anthology Cinema Purgatorio, its 18 installments later collected in 2021. In 2017 he teamed up with Pat Mills for a final time as co-writer on the Serial Killer prose novel, a scabrous dissection of the British comics industry. Despite Mills’ antipathy to the comics establishment, he and Kevin had produced two final Nemesis strips for 2000 AD in 1999 and 2016. After the final League storyline, Alan Moore announced his retirement for comics, with some assuming that Kevin had withdrawn from the medium as well. But he later announced that his love for comics was still strong, and that he would happily create further strips if the concept appealed to him. Subsequently, he did indeed draw two further strips with writer Garth Ennis: a Kids Rule O.K. story for Rebellion’s Battle Action anthology hardcover, and a new Bonjo from Beyond the Stars short for 2000 AD's upcoming 2022 Christmas issue, a return to his light-hearted character that will end Kevin's professional career where it began 45 years earlier, at the comic where he first made his name.

In an industry that could often default to a mass-produced conformity, Kevin was that rarest of things, truly unique, with an artistic voice that was unmistakably his own. In his long career he never once tried to fit in or compromise; indeed, he was seemingly incapable of being anything other than himself. Many creators struggle to make their mark, but with Nemesis the Warlock, Marshal Law and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Kevin was involved in the creation of three memorable strips that will live long in the affections of their readers. He was always, completely, brilliantly original.

As an artist, who could ask for more?