A few weeks ago a set of three letters written by Hugh Hefner to Jack Davis were listed on Heritage Auctions, giving comics historians a rare insight in to the intense micromanagement-style editorial control the Playboy publisher exerted upon his artists. The letters, concerning a Davis gag cartoon that ran in the February 1959 issue of Playboy, gave extremely precise instruction on revisions to the single page work, as can be seen below:

“Oh, man. It’s a good thing that I wasn’t working [directly] for the guy [Hefner],” says illustrator Bill Stout. Stout, who wrote the introduction to Jack Davis: Drawing American Pop Culture, worked as an assistant for Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder on their long-running Playboy strip Little Annie Fanny in the early 1970s. “It would have been a short gig. I would have just bailed. Life’s too short.”

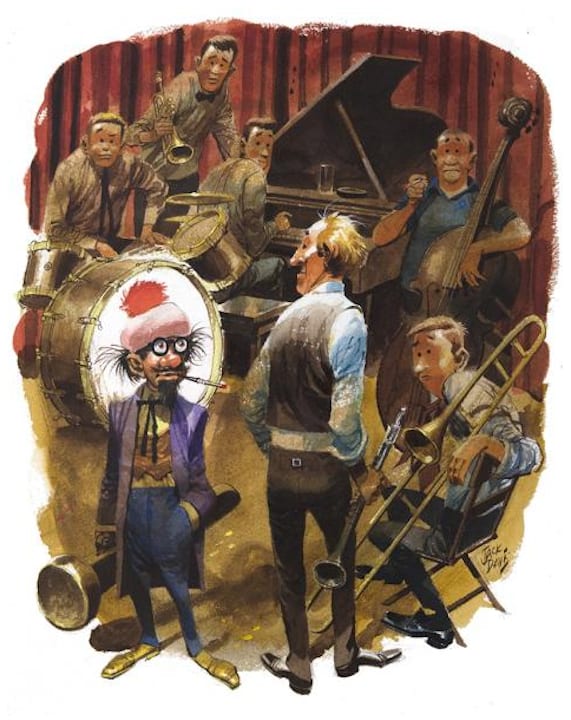

Given the speed in which Davis worked, Hefner’s directions were likely less bothersome to him that they were to others, as we’ll see below. And, anyway, gag panels were not usually his “thing.” The work, captioned “Take Me To Your Leader”, appeared in Playboy during a transitional period of Davis's career, shortly after his departure—along with Kurtzman and Elder—from Mad to launch the short-lived Hefner-financed humor magazine Trump. Davis, of course, would soon become one of the most famous illustrators working in magazines, movie posters, and record albums, and the Playboy piece was among the relatively few number of gag cartoons he produced during his long career.

“Jack was advanced money for Trump that he didn’t earn back, and so he owed Hef and the only way to pay him back was to do those gag cartoons, which he didn’t ordinarily do,” says Denis Kitchen, a long-time friend of Kurtzman and co-author of The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics.

The extreme style of art direction Hefner displayed in the letters above was also experienced by Stout during his work on Annie Fanny:

“The way it would work was that Harvey would do a full-sized black-and-white pencil story submission for Hefner, with dialogue and everything, and tonal values, but not color. And that would come back and Hefner would have changed a bunch of the dialogue and stuff. And then Harvey would do really, really detailed pencils and then I would transfer those pencils to a board the size that we were doing the Annie pages, and I would correct any anatomical errors that I saw. And then by that time Harvey would have finished watercoloring the black-and-white Xerox of the pages, and then using that as a guide I would start to water color the pages and build that up to about halfway done and then hand it off to Willie. Willie would then do a finished painting, which looked like a ‘Persian miniature,’ and then it would go back to Harvey, who would lay a tissue sheet over it and make 300 corrections on each page. And then it would go back to Willie and he would make those corrections. And it would go back to Harvey and Harvey would lay a sheet over it and make 150 to 200 more corrections. Then it’d go back to Willie, he’d make the corrections, it’d go back to Harvey and then there would be about 100 more corrections. And finally about that time, it’d be finished. And I asked Harvey, ‘Why on earth are you doing this? No one is going to see half the stuff you’re correcting here.’

“And Harvey said, ‘If I didn’t, Hefner would.'”

A 1955 letter to Hefner from Jack Cole, perhaps the most renown early Playboy cartoonist, displays similar caution on the artist's part:

"From what Cole writes in this letter, one can infer a very detailed management of Cole's work by Hefner," says comics historian, long-time blogger on Jack Cole and Comics Journal columnist Paul Tumey. "Cole seems a little unsure of his submission ... 'hope that was the right move.' Cole expects that there will be 'corrections and redrawings' on another piece... I guess, for the money Hefner paid, he got to put these guys through the mill."

In Art Spiegelman's book Jack Cole and Plastic Man, Hefner is said to have "grown up reading and loving [Cole's] Plastic Man." Kitchen believes that Hefner’s obsession to detail in the art lay in the fact that he was himself an amateur cartoonist and saw himself as a collaborator with some of his favorite artists when their work appeared in his magazine.

“I think that next to women, [Hefner] liked comics best,” Kitchen says. “He had a particular interest in the cartoons in the magazine and he genuinely respected Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder and Jack Davis, who were all original Mad and Humbug guys, so I think that they got disproportionate interest from him. He couldn’t have conceivably communicated with everyone in that way. There wasn’t enough time in the day. But I think as a quality control matter, he wanted Playboy to be the best it could be.”

“You have to put these letters in context, that he was a ‘fan boy’ who suddenly had power and money. That’s the essence of it,” says Kitchen. “I think he very much wanted to collaborate [with his artists] because the other part of it was he was himself a frustrated cartoonist and if you look at his stuff, it was a relatively simple style and not anywhere in the league of the guys he ended up hiring. But in his mind, he was a cartoonist. He produced at least one published paperback and it was a career fork he didn’t take. So, when he had a chance to work with the very best, he couldn’t resist meddling. I think he couldn’t resist imposing his will, basically, on these guys as a collaborator.”

I think those early Hefner cartoons show that he had plenty of heart, but little talent or native understanding of cartooning," says Tumey. "Not only the individual cartoons, but the overall layouts of the pages show little promise. As we all know, it's possible to be lousy at drawing and still be a solid cartoonist if you can write and master the visual iconography of comics -- but the writing in these early Hefner comics is pretty lackluster, as well. Those 1951 Chicago comics [from That Toddlin' Town] really make a case, I think, for Hefner's strong desire to join the brotherhood of professional cartoonists while demonstrating just how limited his ability in that area was. It must have been a dream come true for him to be in a position to work with supremely gifted cartoonists like Jack Cole, Jack Davis, Gahan Wilson, and all those other guys."

According to Kitchen, while Hefner was a comics fan in general, it was Mad in particular that he "zeroed in on when [he created Playboy]. He and Harvey had a mutual admiration society because Hefner himself was admirable in his own way because he was a pioneer in the field of, let’s just say ‘men's magazines that had class.’ So I think Harvey was part of that generation that saw Playboy as a very exciting and revolutionary thing. And the fact that it had intellectual content, you know, it made the package ‘okay’ then. The ‘nekkid’ ladies were the exciting part to most readers, maybe, but it really was something you could read and not be embarrassed by and, obviously, the cartoons were an important component.”

Kitchen is in possession of Kurtzman’s extensive archive of his life’s work and is working with the Kurtzman family to index and find an institutional home for it. Included in the materials are significant number of exchanges between Hefner and Kurtzman.

“One of the typed letters from Hefner, I believe is something like 31 pages long,” Kitchen says. “It’s in great minutia, panel by panel sometimes, and story by story. It’s an extremely long letter and it goes in to great detail. I can only surmise, obviously I wasn’t there, but I know that Hefner did a lot of amphetamine in the early days and I can kind of guess that maybe he was up all night, maybe on speed, and went on this tear, you know, on his big circular bed or something. One can only imagine. But it’s clearly something that he’s writing himself, it’s not dictated and he’s looking at whatever art and roughs Harvey had sent and he's finding every little thing in the world to critique or to change or to suggest or to say ‘this idea is not funny,’ or whatever. And so you can imagine being the recipient of a letter like that. It’s overwhelming. It’s like instead of getting notations on the side from your teacher, you’re getting several chapters from a book back as a critique.”

In a 2013 interview with Alex Wood, Robert Crumb recalled finding Kurtzman in tears after receiving one such letter from Hefner.

“It was so demoralizing for Kurtzman to work for Hefner. I remember once being in Kurtzman's house and he was working on this Little Annie Fannie strip for Hefner. Kurtzman showed me these things he's gotten back from Hefner, because he had to send, with every strip, these roughs of the strip for Hefner's approval. And Hefner would send back the roughs with a piece of tracing paper over each of the roughs with these little knit-picky blue pencil changes he wanted made. So Kurtzman showed me these, and he'd been drinking a little, and he just started weeping with vexation, literally weeping. He said, ‘Look at this. Look at what I have to endure with Hefner. Okay, I'm grateful to the man, he rescued me from poverty.’ Kurtzman had a big house and he had an autistic son that cost a lot of money to take care of, so he needed the money. So he did that Annie Fanny strip. But, what he had to endure from Hefner. That always pissed me off about Hefner….what he did to Kurtzman, I can never forgive him. You know, when Kurtman left Mad magazine and then Humbug was a failure, he was desperately doing these comic strips for these little magazines like Pageant and Coronet and stuff like that. And Hefner liked his work. And I don't know if he solicited Kurtzman or how exactly it worked, but Denis Kitchen has these exchange of letters between Hefner and Kurtzman where Kurtzman is trying to submit ideas for Playboy. And Hefner's writing back these criticisms that are so demoralizing. Omigod, it was so terrible what he was doing. He knows he's got Kurtzman on a string, you know? And he's just dangling him on a string.”

In the 1950s, when Hefner created Playboy, and for many years later, it “still wasn’t taken all that seriously by the ‘intelligentsia’ and the kind of people he wanted to impress, the ‘literati,’ and so all he could do was build it in a way he thought was first rate,” says Kitchen. “And in the world of cartoons, to him, hiring Harvey and his associates was his way of having first rate comics, both in Trump and then later, Little Annie Fanny.”

“Some of the changes that Hefner required… sometimes it meant that they would have to go back and change panels that were already painted, or layouts that Harvey thought were pretty terrific,” says Kitchen. “When you go through all the preliminary steps—and Harvey’s steps were substantial—from the concept, to the loose pencil, to the tight pencil, to the overlays and color guides and everything, and then Will Elder, in the case of Little Annie Fanny, would paint the final step and then there would still be changes sometimes. And I’ve seen some letters where Hefner would say, ‘Change the color of that sweater,’ and “Move that table to the left," something that would require poor Will Elder to go in with his electric eraser and erase part of a finished painting and start over, and for Harvey to be the bearer of the message because Elder was effectively working for Harvey and Harvey had to take orders from Hef. And so, yes, I think it did make them cry.”

As meddlesome as Hefner’s over-direction could be, it paled in comparison for the artists to having to work with Michelle Urry, a Playboy secretary who was elevated to assistant cartoon editor for the magazine in 1971. In Bill Schelly’s Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Created Mad, Urry is portrayed as a hated presence by the cartoonists. Skip Williamson, who began editing the magazine’s “Playboy Funnies" cartoon section in the mid-'70s, says that Urry “was horrible to work with."

“I don’t think Michelle Urry did much editing," Williamson says. "Her job every month was to gather all the cartoon submissions together, throw out the obvious dead wood, and give them to Hefner. He would make the picks. She was essentially a filter rather than an editor.”

Kitchen: “At least, in general, Harvey respected Hefner’s opinion. He was a smart guy. They didn’t always agree on what was funny or what was topical or what was appropriate for the strip, but Kurtzman respected Hefner. He did not respect Michelle Urry, who took over as the cartoon editor when Hefner at a certain point just got too busy to have the kind of involvement these letters show. He just couldn’t maintain that pace, so he put Michelle Urry in charge and she was simply someone exercising situational power. She wasn’t a fraction of the editor that Hefner was. She not only made them cry, she made them angry and livid. They hated her. And Hefner was not astute enough in that case to realize he didn’t put the right person in there. She didn’t come from a comics background. She was a pretty girl he gave a job to and he thought she could handle it. From what I can tell, she was the wrong person for that job.”

Hefner tried in vain several times to get Robert Crumb to do work for the magazine. In an interview that appeared in Promethean Enterprises #5 in 1974 (reprinted in D. K. Holm’s book R. Crumb: Conversations), Crumb said of Urry: “Hefner was trying to get me to do some work for Playboy, like his cartoon editor approached me and they offered me a job doing a regular strip for them. I was amazed they would offer me a job like that… That Playboy offer I thought was interesting. The cartoon editor is this slick chick named Michelle… I was over at Jay Lynch’s and she came on to me with the deal for Playboy: said they would give me five hundred dollars a page and I could do anything I wanted, except, of course, show penises or insertion or whatever. I said I make enough money to live on, I’m happy with the money I make, what do I need with those restrictions? It’s funny, in 1966 I went to Playboy and she was the cartoon editor and I showed her my sketchbook and she said it was nice, ‘but it’s not Playboy. Why don’t you try to do something in the Playboy fashion?’ I made a couple of feeble attempts to do their pathetic cartoons, like Playboy-style cartoons, and she said, ‘Ah, that’s not it’… It was real pitiful the way Kurtzman was intimidated by Hefner. I told the cartoon editor, I told her when she offered me this incredible job working for Playboy, the biggest magazine in the country for five hundred dollars per page, and anything I wanted to do except, etc., etc. I had the supreme pleasure to telling her to stick it. She got real indignant and said well someday when the underground comix fad goes under you’ll come crawling to us and you’ll be sorry and all this.”

Long-time Playboy contributor Jay Lynch says he recalls what he believes was the final turning point when Crumb decided to never work for Playboy.

"I was at the Mansion once, when me and Crumb and Kurtzman were there. It was late at night, and the Art Institute had flown Kurtzman in to speak at my class that I was teaching there, and I think this is what did it for Crumb," Lynch said. "We were in the kitchen eating--I was eating an egg-salad sandwich--and Kurtzman took off his shoes in the Mansion. He was walking around in his socks. And Hefner said, 'Well Harvey, what brings you here?' And Harvey said, 'Well, the Art Institute flew me in, they paid for my plane fare, and I'm going to speak at this class.' And [Hefner] says, 'Well, it's good they paid for your plane fare. You can't even afford shoes.' So then Kurtzman snuck in to the other room and put on his shoes and Crumb noticed that he was totting-up to this guy who only had a small fraction of his abilities at communication. They were trying to get Crumb to do some stuff for Playboy; he left a note behind that night. Crumb's girlfriend at the time Kathy Goodell was there with us, and he drew a picture of himself with Kathy with blank expressions on their faces. And it said, 'Thanks for a swell time, Hef!' And Hefner liked it! 'Hey, you really know how to thank a guy!' He didn't notice they had blank, depressed expressions."

With his own submissions, Lynch says that he would often get back remarks requesting changes that needed to be made to the clothing styles of the people in the drawings, "stuff like, 'make the lapels wider,' or narrower. If he was a good guy, 'he has to be dressed in appropriate modern style,' because there were clothing advertisers in the magazine." The strips also couldn't offend tobacco or alcohol advertisers. There was even a period in the late '70s while Hefner's daughter Christie was running the magazine that there was a ban on women wearing high heels in the comics. "The craziest one was the high heels thing. Christie was in charge of the magazine and the idea was that high heels somehow limit a woman's mobility. So for a while it was taboo. In the cartoons at least, I don't know about the rest of the magazine, a woman couldn't wear high heels. But that only lasted six months or so."

"The stuff Hefner wrote me, he wrote on the roughs in red pencil," says Lynch. "And then Michelle would send me the roughs and say, 'OK, he approved this one,' and then she'd go in to an elaborate explanation of why he made the changes. On a lot of the others, he wrote notes on them and he wanted me to resubmit them, but I don't think I ever did because it kind of killed the gag."

While Kurtzman admired Hefner as an editor, theirs was a “difficult relationship,” says Kitchen. “In a way, Harvey felt trapped, or he was trapped. Whether he was or not, one can debate, but he was at that point afraid to start a new magazine. Harvey had left Mad—many would argue that was a big mistake, but he left it. Trump failed. I think to some degree, Hefner felt guilty about that so he wanted to help Harvey, but at the same time he never made money on Trump, even though it was short lived. So that complicated things, and in Humbug, Harvey lost his personal money—not much—but he and his partners lost their shirts on that failed experiment and then Help! was never particularly successful. It lasted a few years, but Harvey was flailing about for something different to do when he sold Hefner on the idea of converting Goodman Beaver into Little Annie Fanny. And the rest is history, in the sense that for the next 25 years Harvey focused on Little Annie Fanny. And most of us who are fans of Harvey regret that, because, speaking for myself, I would rather see 10 Jungle Books than 25 years of Little Annie Fanny. They were beautiful and they were sometimes spot on with topical humor and they certainly had their moments, but that a guy of that caliber spent the last quarter century of his relatively short life on that…it just seems…it could have been better spent."

"I don't know... a lot of that Annie Fannie stuff...eh...would have been better without Hefner," says Lynch. "But it was his magazine. He could do what he wants."

__________________

Frank Santoro and I are currently in Brooklyn, NY at Comics Arts Brooklyn (CAB), so we'll be reporting on all that stuff next week. And many thanks to everyone who has helped fund Frank's plan to create a brick and mortar school for cartooning in our home town of Pittsburgh. Check out the video HERE for more info on that project and see you next week.