TROTS AND BONNIE

BOYD: Where did Trots and Bonnie come from? This is a long-lasting idea; fertile ground. Someone commented to me that it was odd that the heroine of the strip was so passive.

FLENNIKEN: Yeah, that was the whole point of the strip, actually. I wanted to do a strip about not having any opinion. It’s funny, but I still feel that way. I definitely relate to the character. And the dog is all these people who have been in my life who are very helpful to me. I’ll say, “I just can’t understand why this is going on” And they’ll say, “Well, it’s obvious: blah blah blah blah blah … ” [Laughter.] It started with my friend, Jeff Desmond, who I wrote about in an editorial for Lampoon, because he was just a nut, and he’s dead. He died a sad death. But he was maybe the first of those people … I would say, “God, every time I go out with my boyfriend I always get this stomach ache when I come home. What is it?”

And he’d say, “You’ve got the female equivalent of blue balls” [laughter].

And then Pepsi is all these nutty girlfriends I’ve always had. They’ve always been such wonderful, colorful characters. Pepsi is [based on] this one girl that I used to riot with, and she carried a gun in her purse. She was a junkie for a while and she was as tough as nails. And there was this other woman I hung out with from Ithaca, and she was very political and very intellectual — she knew things. They have the answers and they have them right there. They don’t have to think about their response. They have an automatic gut-level reaction, which is pretty damn correct, not politically correct, as much as they know what they want. And I love it, I appreciate it, I think it’s great, but I just don’t have it myself.

BOYD: Pepsi always seems like the one who has a new idea and really asserts it and does it. And then there’s the reaction; then the dog is the ironic, snide commentator at the end of the strip …

FLENNIKEN: Yeah, it did develop into a pattern. You know the comic strip is over when the dog talks. I think that was useful. I hope that wasn’t too much of a rut to be in. I think he performed a function. He was the star of some strips. It wouldn’t sustain him always doing that. There were other things that had to happen. It did become more formalized, just like the artwork became more formalized over the years.

BOYD: In the very early underground ones, I can see a difference, but it seems like most of the National Lampoon strips have a similar look.

FLENNIKEN: Yeah. It got fairly consistent. I stopped doing crosshatching under their feet; stuff like that. I developed these patterns that made it easier for me. That’s good, if people didn’t notice. Although I look at them and I think they all look the same. But that’s true of a lot of cartoonists.

BOYD: It’s not like you changed your style as much as Doonesbury changed … [Trudeau] made the decision to have it drawn differently, have it inked differently. I think he actually does the pencils.

FLENNIKEN: Does he?

BOYD: Yeah. And then faxes it to his inker.

FLENNIKEN: That’s a way to get your work out faster.

BOYD: The only big change [in Trots and Bonnie] was that you started doing the color strips.

FLENNIKEN: The longer strips.

BOYD: I was really impressed by seeing the originals of those color strips. It was just the same as seeing Vaughn Bode’s originals. It’s so obvious how badly the National Lampoon was printed.

FLENNIKEN: I think their color separations were not good either …

EDITING AT LAMPOON

BOYD: Did you have much to do with “LaughtHER” [National Lampoon, October 1979]?

FLENNIKEN: Did you like that?

BOYD: Yeah. I thought it was really funny.

FLENNIKEN: I loved doing it. It was so much fun. That was one of my first projects when I got to the Lampoon. I went from San Jose — took the Volkswagen bus down through L.A., went back across Texas, with the dog and the cat in the car and went down to see my sister in Key Largo, Florida. And I was in Key Largo for quite awhile. I did some strips about being down there. Then I left in a hurry late one night and went to St. Petersburg and I had this house in St. Pete which was just fabulous. It was just a great place to live. It didn’t have as many mosquitoes. And I had some friends there. And I wanted, you know, to just go and hang out. And it was so wonderful I said, “Let’s get a house. This is great.”

And I went to the San Diego Comic-Con from there and came back and Michele and Bernie Wrightson came to visit. They ended up moving down there. But having been in San Diego, I just went through another one of my nutty periods of the “what do I want in life?” kind of thing.

BOYD: Because you saw all these other cartoonists? What triggered this off?

FLENNIKEN: I think I was culturally deprived. Key Largo is hell to begin with, cultural hell. There was no movie theater. There was nothing down there at the time, except people in their boats and all they would talk about was diving and boats. Key West is interesting; Marathon is interesting; Key Largo is shit. It’s just awful. That’s why I left Florida. It was so refreshing to go out to San Diego and be with people in the West, people who are intelligent, people who are young and not aging and dying, like they are in Florida. I was drawn like a salmon swimming upstream; there was really very little thought to it at all. I went back out and I stayed with Charlie Lippincott for eight months. He’s a real interesting guy, he’s a big comics fan, he co-produced the comics movie that I’m in, Comic Book Confidential …

BOYD: He’s a real Hollywood producer. He’s not just interested in comics.

FLENNIKEN: He’s real Hollywood. He was great fun to hang out with; we did a lot of stuff out there. And that was really great and I got this phone call from Lampoon. This was when P.J. O’Rourke became editor-in-chief. They said, “We want you to become an editor. We’ll pay your moving expenses, and your salary,” and so on.

I thought, “Well, I originally intended to move to New York anyway, I guess. This is my opportunity, I guess I should take this. How can I turn this down?”

And it meant leaving California and Florida. [Laughter.] And so I went back and picked up the dog and moved my stuff to New York and I was an official editor. That was a whole different thing, to be an editor there. I did less drawing … Although I did do some ultimately. I didn’t have to meet that Funny Pages deadline. I met it pretty regularly actually.

BOYD: I don’t see a lot of Trots and Bonnies from ’79, but there are some big strips, color strips like “Buster Snellings, III” and “Overachiever.”

FLENNIKEN: “Overachiever” was done in California.

BOYD: [looking at “LaughtHER” article] Are these cartoons by Michele Brand?

FLENNIKEN: Yeah. She was living in Saugerties, New York with her husband, Bernie Wrightson, at the time, [looking at the “LaughtHER” article] I worked on this with John Wiedman. John Wiedman has done a lot of Broadway work. He did the book to Pacific Overtures, and a lot of musicals. You still see his name [on Broadway]. At Lampoon I got to hire people to do things and I got to tell them what to do … I wrote this editorial and I got all the editors at Lampoon to dress up in drag. And it was really, really fun. I got to art direct all the photography; I don’t remember what the thing was with that particular strip. But we did “LaughtHER” T-shirts for this ad … see, it doesn’t really work. She’s supposed to have only one breast. Unfortunately, you can’t really tell that. The interesting thing about “LaughtHER” was that it parodied something that didn’t really exist. There was no women’s humor magazine that existed, as opposed to most magazine parodies in Lampoon which were based on existing magazines. The weirdest thing about [“Laught-HER”] was doing this comic strip. [Laughter.]

BOYD: So, you just had to hire a bunch of guys and photograph them naked.

FLENNIKEN: It was all work! It was really weird because we had to get these guys to work for real cheap. So we had to say, “OK, we need a bunch of guys who’ll take off their clothes for $50.” You can imagine what kind of guys would do that. And then, when they were there, I thought, “We’re going to have to get them to take off their clothes.” And I said, “Well, we’re going to have to pick the one with the cutest butt here, but we don’t know which one has the cutest butt until they all take off their clothes.” So, we’re going to have to shoot this picture first, and then she’s going to have to go stand up in front of them … One of these guys actually was holding his clothes in front of him. He wouldn’t expose himself and we had to airbrush the clothes out of there from in front of him. We decided on this guy. He was French. But [during the photo session] we had the total cosmic giggles. “Oh God, this is so funny. I can’t stand it! It’s so horrible! We’re treating these men like meat! Oh, no!” It’s embarrassing making men take off their clothes. It really was. But we were very responsible about it. And helpful.

BOYD: How long were you an editor there?

FLENNIKEN: A couple of years. I got to go to both the Republican and Democratic conventions in 1980. That was real fun. And I did a lot of projects that I really liked — well, that I both liked and didn’t like. Ultimately, I quit Lampoon because everything I did had to go through P.J. and it was really frustrating to me because I could use my own taste to a certain extent, but then sometimes I would have to second-guess what he would like. And I just couldn’t do it … When I first started working at Lampoon, I had to go through the old inventory files and cull out what could still be used and return the rest to the artists. I came across an incredible strip by a guy named David McClelland. It was called “Weak Ego Comics.” The dialogue balloons had three levels … ego, superego and id. The character would meet someone on the street and the ego part would say “How ya doin’?” and the id would be saying “I want to kill you!” I went to the other editors and said, “This guy is great! Why haven’t you been running this stuff?”

They got very strange, uncomfortable expressions on their faces and they finally told me that the cartoonist had jumped off a roof somewhere and killed himself. I found out later that he had drawn comics during the student takeovers at Harvard in the late ’60s that some people believed were the most succinct political statements made at the time. I felt very strongly, then, that the magazine was somehow to blame for the waste of this talent, not having printed his work. It probably wasn’t true. Do you know who Jane Brucker is? She was in the Funny Pages for a while. She’s an actress. She played the little sister in Dirty Dancing. She’s a cartoonist. And I was very interested in putting more women in the magazine. P.J. said, “Go talk to this Jane Brucker about her comics.”

And I talked to her and I said, “Jane, you know your writing’s real good, it’s real funny, but your line work is real, real simple rapidograph. I really think P.J. is going to want you to put more lines on the page and maybe change your pen and stuff like that.”

And I walked in to talk to P.J. about it and so he goes, “Ah, the artwork’s fine. She doesn’t have to change a thing.”

She’s also real gorgeous and sexy; I think she could have done anything she wanted for these guys. They just loved her up there. I felt like a dork. I didn’t care whether she had to do more line work or not, because humor was the point. It was stupid for me to waste my time telling her to change her work. And then there were some cartoonists that were really good that he just didn’t like. He never liked them, or didn’t like them enough to stick up for them. This one guy, David Simpson, did three strips that were just wonderful, neurotic, funny, great concept, crudely drawn but really funny stuff. And he’s a wonderful talent. He’s written a novel. Some people like his work and some people don’t. But he’s really funny. And some of the Canadian cartoonists … David Boswell, Rand Holmes, Marv Newland. Tim Eagan is another one that I really liked and couldn’t get in. He was from Monterey and he had this wonderful concept of a guy’s brain and a bunch of guys running the brain like a submarine. They’re inside the brain and inside the body. The whole strip happened inside the body. It was a really neat concept. Sid Harris did one strip, which worked, about a Jimmy Carter kind of president who lived in an apartment in New York and took the subway to work. That was real cute for a while. It was frustrating to me that they didn’t have more cartoons and that they wouldn’t give people more room to expand. Tons of people, they had tons of people. I still have these people’s artwork on file. You know another one who I never could get in there? Frank Stack. He did Dor-man’s Doggie. I love Dorman’s Doggie. He’s a great guy. And he’s totally, reliably consistent.

BOYD: When you were editor, were you cartoon editor or a free-floating editor?

FLENNIKEN: Free-floating editor. Theoretically I could do whatever I wanted to. I mean, I wrote a couple of pieces …

BOYD: Tony Hendra describes [Lampoon] as a bunch of editors and people would just get different projects.

FLENNIKEN: They had an editorial meeting every week or so. You would come in and there would be an issue editor — there’d be P.J., the main editor and the issue editor, and an issue topic. You would come up with your own topic, or somebody would lay it on you. And then people would theoretically jam out ideas at that meeting. Or else they’d come in — John Hughes always came in with a long list of things that he’d thought out. And then you’d go from there. So it was whatever you wanted. Like if I said, “I want to do a comic strip about blah, blah, blah,” I could do that. Most of the time I didn’t know what I wanted to do. It was fun. I got Rick Geary in there; that was one of my favorite accomplishments. David Scroggy, who is his agent, had sent me Rick’s teeny little books that he did. Did you ever see those? I knew that there was something in them. I took the books, xeroxed every page, cut up the pages, cut up the panels, and laid the panels out in 12-panel pages. I took in this page to P.J. and I said, “I want this. I want to print this.” And he said, “Great. Let’s do it.” That was an easy one. There are a couple of other people … Holly Tuttle was another. I was happy when Holly was in there; that was short-lived, but it was great while it lasted. I went through her sketchbooks and xeroxed her drawings and said, “I want to do like the New Yorker, only funny. Those little filler drawings in the New Yorker. Let’s run Holly’s sketches.” So we did that for a few issues. That was wonderful, then she did a strip for a while in there. So, that was really fun, doing that stuff. I felt like I was rewarded with that. And then I found Mimi Pond. Mimi had sent me a bunch of her stuff that she was doing in the Bay Guardian. She had these little panels; it’d be a person sitting 5 in the panel and then this long block of type, this rant. And I liked it. And I’d sift through all these submissions, like “Tommy Toilet” that was drawn on toilet paper … a lot of stuff that you don’t want to deal with. And I was so conscientious … I used to write these people and call these people and … [laughs]

BOYD: I bet National Lampoon gets a better class of submissions than Fantagraphics does.

FLENNIKEN: Really? Did you ever get anything on toilet paper?

BOYD: No. I have to admit. [Laughter.]

FLENNIKEN: This woman called me and was going, “I sent you something and nobody ever sent it back to me.”

And I said, “I’ll look around for it. Can you describe it?”

And she goes, “Well, it was on toilet paper.” [laughter]

I took Mimi Pond’s cartoons to P.J. and he said, “You know, you’re right. This woman is a find.”

And I arranged to meet her in San Diego, and I hung out with her and had her come out and visit me and hang out with with me. And I just showed her how to work in comics form. It was real easy because she was a quick study. I just said, “You just divide this up and put this in boxes, instead of that.” She picked right up on the way a cartoon rhythm should go …

BOYD: She wrote at least one of The Simpsons episodes.

FLENNIKEN: She’d wanted to do that stuff. She’s super ambitious. And the convention was great. [Lampoon] finally gave away free copies of the magazine …

BOYD: At the San Diego Convention?

FLENNIKEN: Yeah. Flew cartoonists out. I got Lampoon to put up money to fly them out … We flew to a number of comics conventions. One was in Toronto … That was one of the things that I felt, going in: that Lampoon’s comic readership was a real hardcore audience and that they should build on that audience and really give that audience something back and create a real thing there. Strengthen that. They sort of did that at times. And then with Mimi, I guess it was just the straw that broke the camel’s back. I arranged to have Mimi do this series of articles, and it got turned down in the magazine in a really off-hand way. So I ended up saying, “What? So this means that this is not going to be running in my issue?”

And it’s like, “Yeah.”

And I said, “I’m leaving, screw you. I can’t deal with this any more.”

I was just being petulant, really. I shouldn’t have left, but Doug Kenney had just died and I was real bummed. I should have stuck in there just to keep things going. But P.J. quit soon after that, and his secretary quit, along with several others … I think we were all just depressed.

BOYD: So, you just freelanced for the National Lampoon in New York after that?

FLENNIKEN: I did a lot of stuff.

BOYD: Didn’t you say that you wrote film scripts?

FLENNIKEN: Yeah. I did that. I did one when I was at Lampoon. That was another grinding, wearing, weird project … but it got made.

BOYD: What was it?

FLENNIKEN: National Lampoon Goes To The Movies. And then it became National Lampoon’s Movie Madness. It’s available on videocassette. I just got a royalty check from it for $32. It was originally the second movie deal after Animal House. And the original idea was decent. It was 10 parodies of movie genres, which would make it in 120 minutes, 12 minutes apiece. And if you count the time the credits roll it makes it maybe 10 minutes apiece, which is a reasonable amount of time to expect you to sit through a gag. It’s long, actually. Ten minutes is a long time. Five would have been better. And what happened was [the project] finally got whittled down to four stories. Four got shot. Three ended up in the movie. And three segments in 120 minutes — it was probably 90 by that time — was half an hour a piece. There was violence in the theaters, [Laughter.] So I heard … and I think that people, after Animal House, did not expect to go into a theater and see a parody of The Other Side of Midnight. They were not prepared for it. The people that loved Animal House didn’t ever see the original The Other Side of Midnight so how are they going to get any of the gags in National Lampoon’s The Other Side of Midnight, right? And the Joseph Wambaugh parody, which was kind of funny because it had Robby Benson playing guitar and singing “Feelings.” That was pretty amusing. The other one was a parody of Kramer vs. Kramer, which was sort of cute, but while it was being written I said, “You guys, these are too long. You’ve got to edit these. They’re taking too long.” [Their response was] “Don’t worry about it. Don’t worry about it.” OK; I’m not supposed to worry about it … Another thing that was sad about that project was — it’s like what you asked about why they didn’t publish their own cartoonists’ books. Lampoon had a wealth of stuff associated with Lampoon, that people loved, and yet they were doing something that was totally divorced from Lampoon and that other stuff. They could have just taken stuff from the pages of the magazine …

BOYD: That’s what they did with the records and that worked. Those were pretty successful.

FLENNIKEN: Yeah. When John Hughes did Vacation, it came from a story that was in the magazine. It was consistent, so it was a hit. I think that was real important. That was one of the things that was wrong with [Movie Madness]. But it did get produced. Then I did a movie for Disney called Silicon Valley Guy, which was never produced, because it was ultimately caught up in a change of executives at Disney and they’d just lost $30 million on Something Wicked This Way Comes … it was a bad time for Disney. Silicon Valley Guy was a movie based on a book, based on the Silicon Valley Handbook, which was based on “Silicon Valley Guy,” a single, a 45 record which was marketed by mail from the people who made it in Phoenix, Arizona, which was a parody of …

BOYD: Valley Girl, right?

FLENNIKEN: It was fun. It was interesting. I had to learn about computers to do it. [Working on a movie] is real fun, compared to cartooning. You get to have a lot of stuff happening that you couldn’t have in a cartoon. You can do tiny little movements that you wouldn’t want to waste a panel on in a comic strip. You can say, “She blinks frequently,” or something. You can draw in more of the details; you really wouldn’t be able to do that in a comic very well. Some people can …

BOYD: Besides doing Trots and Bonnie and these things, what else were you doing?

FLENNIKEN: There was this book, The Seattle Restaurant Guide; I did the cartoons in there. I did that while I was in New York, and it really made me want to be here … Also, I illustrated Bruce Fierstein’s Nice Guys Sleep Alone. It was published by Dell Books. That was fun, and it was nice to do the color. I did another cover for him, for a book called East Side Eats, which is about where to eat in Bellevue. I did that like a Monopoly board. And he paid extra to do it in gold foil lettering … That was real fun for me; I like to do this really mechanical stuff, like designing logos and lettering … you’re immersed in the work. It’s really mindless … I did a lot of advertising stuff for Toys ‘R’ Us and Burger King and Sears. I did Animatics … do you want to see an Animatic that I did?

BOYD: What is an Animatic?

FLENNIKEN: Well, this is rudimentary. You do a drawing and then you go to a video studio and they can change the color just using the video equipment. If you want a ball bouncing through the frame you don’t draw a number of balls, like in animation … you just draw one ball, cut it out, they put it on there and then they move the ball. That’s how they do it. They do them in advertising when they’re going to do a commercial. They want to show the client what the commercial is going to look like, but they don’t want to actually film the commercial because it’s too expensive. So they’ll do an Animatic to give them an idea and they’ll play music over it.

BOYD: Was this what you did these for?

FLENNIKEN: Uh-huh. Artie Spiegelman got me this job. This was for a guy who was directing station ID spots for a TV station in Minneapolis.

BOYD: Spiegelman got you this job?

FLENNIKEN: Yeah, he recommended me. I thought that was real nice of him.

BOYD: He, apparently, has gotten everybody in underground cartooning paying jobs somewhere. He got the people in Raw jobs, too. It wasn’t like he expected them to starve. So basically, you did these for …

FLENNIKEN: I did these in about a day.

BOYD: For an advertising company that was trying to sell this to Scott? Or was it actually for Scott directly?

FLENNIKEN: No. It was for J. Walter Thompson and they were trying to — I think they either had the Scott account or they were trying to get it. In fact they made those commercials. They became real live action commercials. They must have had the account. The Sears one, for instance, was not something they already had.

SEX AND LOVE

BOYD: I guess we should bring this up to the present unless there’s something that we haven’t discussed yet …

FLENNIKEN: Some big thing? When I was in New York I had a lot of projects that never quite flew. One was a guidebook to sex without love. [Laughter.] That was fun. One of my favorite topics …

BOYD: Sounds like a ’70s project.

FLENNIKEN: It was. My friend Beth and I were totally disillusioned and we decided that we would do this book. The cover showed a guy’s bedroom, and the guy is on his way out the door; he’s pulling his pants on and this woman is sitting on the edge of the bed with her phone and her little black book in her hand calling some other guy. We would get together and we’d write this thing and we’d laugh until we wet our pants. It was so funny.

The whole introduction to [the book] was “Shary” and “Beth” sitting in a restaurant talking about modern life and how we decided to do the book. And then, in lieu of payment, “Shary” blew the waiter. We were in hysterics doing this. I had this vision of going on talk shows in character, with the book, being a total whore. It just gave me the cosmic giggles doing that. And it was just pre-AIDS, and probably too gross for anyone to handle anyway, but there was actually real good advice in it. Like how to get picked up in a bar. We actually had someone who was really good at getting picked up in bars and she had all these techniques … it was wonderful. Stuff like, “When he looks in your direction, throw your eyes to the floor, then look back at him very briefly. Sit near the door so you can eyeball what walks in.”

Stuff like that. I tried it and it works … to a point.

BOYD: This was a book, right? Not a comic. But was it illustrated?

FLENNIKEN: It was a handbook, so it would have a lot of different kinds of formats and maps. And then I did an article in Playgirl … Well, first I did “Dead Boyfriends,” which was an editorial in Lampoon about my dead boyfriends, dead and wounded ones. I can give you a copy. And then I did “Boyfriends.” That was for Judy Brown, an editor at Playgirl. It was her idea to begin with … I wrote this really hot piece. It was a lot of fun to write. It was a first-person view of this women masturbating when she has her period and what it’s like to fuck someone you don’t love, from the woman’s point of view. Just this really intense graphic stuff. And then a little quiz. And they ended up cutting all the real meaty, sexy stuff out of it, but they left the quiz. I was so outraged that Playgirl would be doing this … I expected Playgirl to accept material that would portray real sex for real women, that would turn women on. But they showed the article to a couple of their secretaries, and apparently they were disgusted. There goes my fantasy of being God’s gift to women’s sex magazines … [laughter] So that was kind of disillusioning.

BOYD: But then Playboy doesn’t have much stuff that makes fun of sex.

FLENNIKEN: Yeah. Those people can be as prudish as anybody.

BOYD: Well, they’re serious about their chosen subject matter.

FLENNIKEN: Yeah … Well, I don’t know whether I’m a born pornographer or what. I really believe in writing about sex. I guess I could get out of the habit of doing that kind of material, but there’s something really visceral about it and I really like it. And I think there’s a purpose for that. I really believe in writing about sex. I was in the shower room at the pool the other day, surrounded by naked women, thinking about how secrecy about sex has done such incredible damage to people’s lives. To make them feel such shame. It sure screwed me up. But so many people have had to pay with their lives because somebody male made them feel shame about getting pregnant, or being gay. It was during my formative years that Dick Gregory, before he got into that liquid diet thing, and Lenny Bruce — Saint Lenny, who died for our sins — were saying that the only way we could fight all that repression was to talk about it a lot and say all those dirty words until they didn’t sound so bad anymore. This meant a lot to me because my father used to batter me for saying words like “shit” and “fuck.” That was when I was eight years old, and had no idea what they meant. I was just bringing them home from the playground.

I’d love to be doing a Trots and Bonnie strip right now about Basal body temperature and cervical mucus … that’s how you know you’re ovulating, you know, and can get pregnant. I’m just learning this at 40. Why didn’t they teach this stuff in health class? It would be so great if teenage boys could stick their fingers in and check their girlfriend’s cervical mucus … But it must have something to do with my childhood that I just like talking about the stuff you’re not supposed to talk about.

BOYD: Most of your strips are about sex in one way or another …

FLENNIKEN: Yeah, that’s partly because they were for Lampoon. Their editorial policy is — or was at one time, anyway — “don’t do anything you can do in a straight comic.” I was starting to feel really alienated from Lampoon in general. There wasn’t really much happening and it got to where I felt like I was writing for three child molesters in prison somewhere in Illinois.

BOYD: Obviously, you never see real letters in National Lampoon. But did you get letters?

FLENNIKEN: A few. Someone wanted me to design a Trots and Bonnie tattoo. I got one from Australia that called me a female D. H. Lawrence. I liked that. “Yeah, you have the idea. You got the joke.”

And that’s great, because [Lawrence] was persecuted for the work he did, his art shows and …

BOYD: I didn’t know about his art shows. I just know that he was obviously persecuted for his novels.

FLENNIKEN: D. H. Lawrence did a painting of a shepherd masturbating under a tree with a line of nuns walking past. And whatever it is that makes me want to do this stuff I would think he had it too.

BOYD: I was really surprised when you decided not to go with the sexy story for the Misfit Lit show …

FLENNIKEN: Which one?

BOYD: The one about the student who screws all her teachers but can’t get one of them interested, but finally does.

FLENNIKEN: Well, that story doesn’t hold up for me. That’s a real person I was writing about.

BOYD: Oh, really … maybe she would have come to the show and been offended.

FLENNIKEN: And maybe “Rose, Rose … ”

BOYD: Where she becomes president?

FLENNIKEN: Maybe that story says the same thing more clearly … I really wanted to do a story about somebody who screwed around to get someplace. And I think that it’s not the context of the times now. There’s nobody really doing that much anymore. Actually, it’s my theory that nobody’s having sex anymore. [Laughter.] I could talk for hours about sex … a lot of women can do that, though. That’s what they say, that women get together and their conversation is very sexual. It’s a female kind of trait, because it’s a real female power base. So I’m not sure that it’s particularly unusual … Obviously, all these other women cartoonists draw a lot about sex.

BOYD: Thinking of the women who were in the Misfit Lit show … every one of them had some kind of sexual theme in their work …

FLENNIKEN: It’s funny; we all probably have something that we don’t like that’s just as silly. I always disliked cartoons — and I don’t like songs — that are like: [sings] “I have a problem with my boyfriend … ” [Laughter.] I guess I’ve done enough of those; I certainly could have done those in my strips, but there was some line I was drawing … the strip about the high school Idi Amin isn’t about sex. What happened? It’s about death …

BOYD: It is in the context of National Lampoon, which is sexist on every page, practically …

FLENNIKEN: I’ve been really complimented when people do tell me that they jerk off reading my comics … I think that’s a really vital, gut-level reaction … Don’t you think it’s a positive reaction? If you can do something that arouses somebody …

BOYD: Yeah, but that’s not your intention when you do “Sex and Love,” or “One Night in the Life of Peter Torpid and Ellen Anodyne … ”

FLENNIKEN: Well, I don’t think that would turn anybody on …

BOYD: Or “Rose, Rose, There She Goes, Into the Bushes to Take Off Her Clothes … ” You weren’t intending to turn people on, were you?

FLENNIKEN: No! Those strips were meant to depict the pathetic side of sex, which in my opinion is pretty ubiquitous. But there were lots of nude scenes.

BOYD: Don’t you find it weird that people get that kind of reaction out of these comical, satirical strips?

FLENNIKEN: Mostly I want to be understood, for them to get what I’m saying. But I’ll settle for any reaction. It was a big deal for me to draw naked men with their penises showing in Lampoon. I wanted to put [Michelangelo’s] David on the cover, with girls making fun of his little weenie. I wanted an equal time thing because what men don’t seem to realize is that we all have the same reaction to seeing someone of our sex naked. It makes us nervous. We compare our bodies to the ones in the picture. It’s made women totally nuts. Unfortunately, the men at Lampoon got nervous and told everybody that we couldn’t draw penises anymore. Even the little tiny blips in the boys’ locker rooms had to have jockstraps painted on them. One of the Trots and Bonnie strips that most men mention to me as having had an impact on them is one of the early ones, with a very anatomically correct naked young boy on the beach with the girls. Guys will say, “Yeah, I looked just like him when I read that.” I’ve done a couple of things that people really remember, like the one where the dog was going down on the little girl, from The Tortoise and the Hare … my entire family got on the phone when that came out. I sent them a copy of that. Basically, my mother saw everything I did. I don’t know how she related to it … [Her response was] “Oh, that’s very nice, dear, but you spelled this wrong … ” They were unhappy with that, because my father was still alive, and he was a prude. That was something that provoked a really strong reaction from people. I’m not the only one who’s ever thought of that thing happening! I know lots of people who make mention of that. It was really important to me, knowing that kids did that: real kids did that with their pets. And boys did that with their pets, because they told me about it. Some pets — not all pets — some kids and some pets … It was really important to me that that stone get turned over and allowed to have some light shed on it.

BOYD: But nobody said that they masturbated to that strip, did they?

FLENNIKEN: No one actually said they masturbated to that one, although so many people mentioned it. “I really like that one you did about the girl and her dog … ” [Laughter.] Nobody ever really went into detail about why they liked it, and I just assumed it was because it struck a nerve. It’s not just that people masturbate to it … that is masturbation. That is sex. That’s all right there in the story … I wanted to put it there and not have it be dirty. It’s not dirty, it’s not bad … And there’s another one I did about Trots reading a dirty book and Bonnie jerking off in the bathroom. I did it because I felt that when men draw and write about women masturbating they don’t do a very realistic job. And I really felt more motivated then than now, because people were more sexually open when I did those in the ’70s. But I wanted to say, “Hey! Here’s a voice, too.” You need a number of voices. You don’t need all the same voice.

BOYD: Well, I find that totally legitimate. But maybe it’s just my own reaction; I just can’t get aroused by a comic book.

FLENNIKEN: That’s OK. I mean, my ex-husband used to jerk off looking at Minnie Mouse … [Laughter.] And he’s not the only one who did that. If you consider that writing in some way can be erotic … I mean, anything can be erotic. I don’t think it’s intended … I have a real hard time relating to that real standard kind of porno, ’cause everything looks so nasty. All the women are real mean and colorless and heartless … they really are just cunts. Who gets turned on with that stuff? I don’t know. I’ve read gay pornography; it’s really interesting. Gay men’s magazines … I don’t read them frequently, but my girlfriend gave me a couple she had. They’re really hot. And they’re hot for women to read. They wouldn’t do a thing to you. They’re all talking about how manly the guys are. Hairy chests, you know …

BOYD: That seems just to be a reflection of what Penthouse or Playboy does …

FLENNIKEN: Well, no, because they’re oriented towards females.

BOYD: That’s what I mean …

FLENNIKEN: But for a woman to get aroused … I see what you’re saying. That may be true. So this gay stuff is like the two cowboys who are stuck in the bunkhouse together all night. [Reading that, you think] “Wow, that sounds like fun!” Big hairy guys, and they describe their muscles in detail … “OK, great,” you know?

BOYD: Maybe I’m wrong, but I always heard that it was mostly gay men that bought Playgirl.

FLENNIKEN: I heard that too. It’s such a disappointment … I don’t know. It’s definitely not the only vehicle going in terms of that kind of material. I do know that some of the other stuff I want to do has as much appeal to me as stuff about sex. I guess it’s just that I really want subjects that grab you … The Eros comic that I liked the most was Domino Lady, the one with the car chase in it. You weren’t afraid to turn the page …

BOYD: … you know that people are just going to be in car explosions.

FLENNIKEN: I really liked the car chase. I like car chases.

BOYD: So, is that maybe a new direction for you … to do a lot of car chase comics — action comics, and violent stuff?

FLENNIKEN: Well, it might be fun to write that stuff. You saw the collection there that William Novak did?

BOYD: Yeah; what is it?

FLENNIKEN: He did The Big Book of Jewish Humor, which has one of my things in it, and this has a four-page strip in it. He’s a really neat guy. He did the Nancy Reagan biography.

BOYD: Really? Where’s your strip?

FLENNIKEN: It’s in the middle of the book. It’s a kind of Fatal Attraction story. I did it before I saw Fatal Attraction.

BOYD: Was this originally in color, or was it black and white?

FLENNIKEN: Black and white; it’s done on Duo-tone board, where you use the chemicals to get the gray tones. It was real fun to do that.

INFLUENCES

FLENNIKEN: What do [some of the other people interviewed by the Journal] talk about?

BOYD: It’s different for everybody. People talk about their influences … those are the standard questions. They’re almost like a joke.

FLENNIKEN: You don’t want to hear my influences? You have to know, because there’s a quiz …

BOYD: By you?

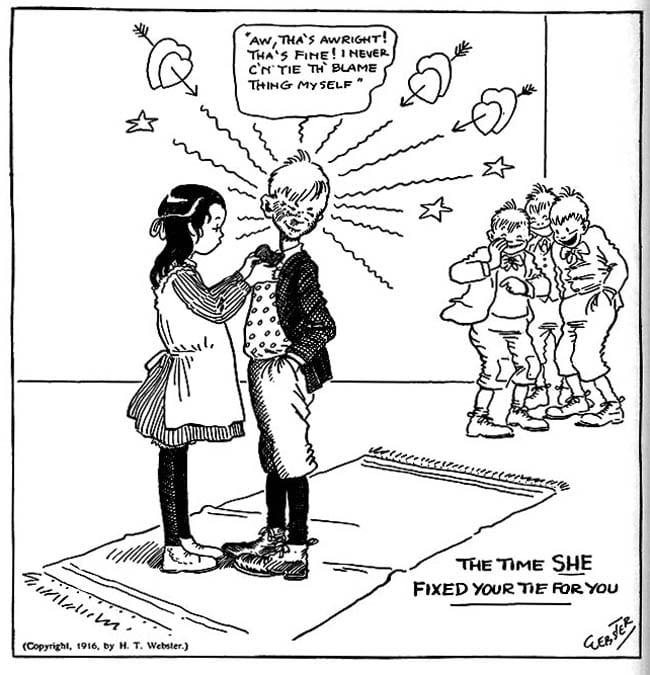

FLENNIKEN: Not by me, but people who know … it’s real obvious. There’s H. T. Webster. He did Caspar Milquetoast, The Timid Soul and some other strips. He did some beautiful, funny little things. I loved him. My father used to go have dinner with H. T. Webster’s mother. And with a guy named Ronald Coe. Coe was crippled somehow, he had polio or something, and he became a cartoonist. And my father went on to the naval academy, but they both had this cartooning thing planted in them from hanging out with H. T. Webster’s family in Ohio. He was from Ohio. So there’s this real physical connection there. But my parents always had H. T. Webster cartoons in the house. There was a whole school of art that came from Charles Dana Gibson. They were looking at Gibson’s line-work. And you can see that they were.

BOYD: Was Webster the one who did all the animal cartoons?

FLENNIKEN: No … that was T. S. Sullivant. Besides The Timid Soul, Webster did all these collections — poker, bridge, golf and fishing, and Life’s Darkest Moment, How To Torture Your Wife, How To Torture Your Husband … He had a ton of books out. When I was learning to draw cartoons — when I needed to draw something — I would go to his books to see how he did it … ’Cause I didn’t use crosshatching like that in my early work. This wasn’t always my style.

BOYD: What was it, then? Was it more dense?

FLENNIKEN: No, not at all … these characters, the Pepsi character especially, that’s a character from one specific Webster cartoon. And the Bonnie character was a boy in another Webster cartoon. They’re real specific … My goal, when I did these strips, was to be able to draw what I needed to draw from memory, and not have to look at this stuff. Sergio Aragones can do that. I told Sergio that and he said, “Yeah.” I said, “Sergio, I can’t draw a gun.” And he goes, [makes sound effect of rapid drawing], and draws a gun. And he draws totally out of his head, that guy. He’s fabulous. He has a great visual memory. He looks something up once and he remembers it, I think, because I’ve seen him draw a whole samurai costume and everything out of his head. And I think that [when you do that] you literally use more areas of your brain … you’re activating more areas of your brain when you do that. I have this sort of mental image of the inside of people’s brains …

BOYD: Like more bits of it lighting up, or …

FLENNIKEN: Yeah! And I’ve also read that it takes 21 days to break a habit, because neural paths in your brain have to be re-routed. And if you want to change that habit … to build a new pathway it’s 21 days of repetitive behavior. In other words, if you were taking swimming lessons to learn how to perfect your breast-stroke and you had to learn a completely different kick than what you had been doing in the past, you would feel really awkward the first time you did it. And theoretically, at the end of 21 days, it will be natural.

FORUM ON FEMINISM

FLENNIKEN: “Fun Tattoos For Parts of Your Body” was this two-page spread of pseudo-tattoos I’d drawn on people’s bodies with a laundry marker. I’d done this at a lot of parties. Always a good ice-breaker. So I convinced a couple of women I knew to take off their clothes for these photos. I drew little faces and stuff on their nipples. One of the women said guys were always telling her that her nipples looked like pencil erasers, so I drew that. One was a librarian from New Jersey and the other one was a prostitute, a dominatrix, who was always up for doing something unusual. The librarian was a Lampoon fan. She wanted to work for them badly, and would’ve done anything to get into the magazine. She essentially did when she posed for this piece. That’s her in the parody of the Jordache jeans ad. I think she looks beautiful in this … The guy I found was a homeless alcoholic headed to the depths of somewhere … it was real sad. I felt real bad about getting him to do this, but he was perfect. And then they had to airbrush the feet because the feet were so dirty … [laughter]

BOYD: Wasn’t it easier to clean them?

FLENNIKEN: Well, I didn’t realize the feet were dirty, the photographer didn’t realize it … these people were sweating and I had done every stitch on their bodies with a Sharpie. On their butts. I was not noticing whether their feet were dirty or not. The weirdest thing about this piece is that years later I was at this Women Against Pornography conference, because I was researching another story that I did, and I was watching this anti-porn movie. It’s the one that has the guy, the cartoonist from Hustler magazine and his infant daughter, and it shows his really raunchy cartoons, and then it shows him playing with his kid, and saying, “I wouldn’t want my kid to be bad.” And ironically — or not so ironically — he was arrested years later for molesting his kid. He did Chester the Molester. And then he actually did molest his kid.

That’s one of the weird points they make in the movie. I thought the movie was going to be real heavy-duty … you know, to show how women are degraded, show a lot of real meaty stuff and show a lot of really degraded women and a lot of really pathetic stuff. And instead, they’re showing an erotic baker that puts bathing suits on their cakes. And they’re going “Oh, this is really offensive.”

And I was thinking, “What do you mean? Let’s show some people being hurt here.”

And they start doing this thing about tattoos. And they show somebody getting a tattoo — I think it’s a guy getting a tattoo. And they show a naked woman and they show the blood and they talk about why guys get tattoos of naked women. And then the guy says, “When women get tattoos they’re much tougher than men. They can take a lot more pain.”

And they cut to a shot of this Lampoon piece.

BOYD: You’re kidding!

FLENNIKEN: I couldn’t believe it! I was standing up in the theatre, going “Wait a minute! Those are my drawings! I did those with a Sharpie!”

And it looks like they’re saying pain and blood, and then they show these tattoos and these nipples …

BOYD: Did you point it out, and did anyone respond to it?

FLENNIKEN: I actually wanted to sue them. Well, you can complain, but [making a documentary] is not illegal. It’s not like you can slap an injunction on a film. And they don’t make money, so you can’t get their profits … I went in thinking that Women Against Pornography were, if nothing else, at least part of the avant-garde, socially … because the things that they’ve done legally are real interesting. In Minneapolis they pushed for a law allowing civil suits to be brought by women who felt that they had been hurt by pornography and allowed for very punitive triple damages. This was for women whose husbands, for instance, had seen photographs of women tied up and whipped and went home and tried it on their wives. It was really well thought-out, plan-wise. And after hearing them speak — I heard Andrea Dworkin and this woman lawyer — just hearing them, they’re so detached from reality. And then seeing this film, on top of it … Andrea Dworkin wrote this book called Intercourse where she stated that men oppress women. I think she’s saying that men oppress women because they want to fuck them. They fuck them to oppress them and they oppress them to fuck them. And everything is around sticking your dick in them. She has this whole thing about how intercourse is mandated in the Bible. She recites this passage, and this passage, to prove it. It goes as far back as the Bible, according to her. I think this woman is off her rocker. It’s not intercourse that’s mandated by the Bible; it’s not intercourse that’s important. It’s procreation.

BOYD: Right; it’s building up your tribe.

FLENNIKEN: Absolutely! It’s not sex. And the Women Against Pornography — at least, a large faction of them — are against sex. They don’t believe that people should have sex. That’s really sad, because it’s probably coming from something in their childhood. It’s that they’re not just against tying someone up and taking pictures … I researched it. I didn’t just develop the opinion.

BOYD: What was this research for?

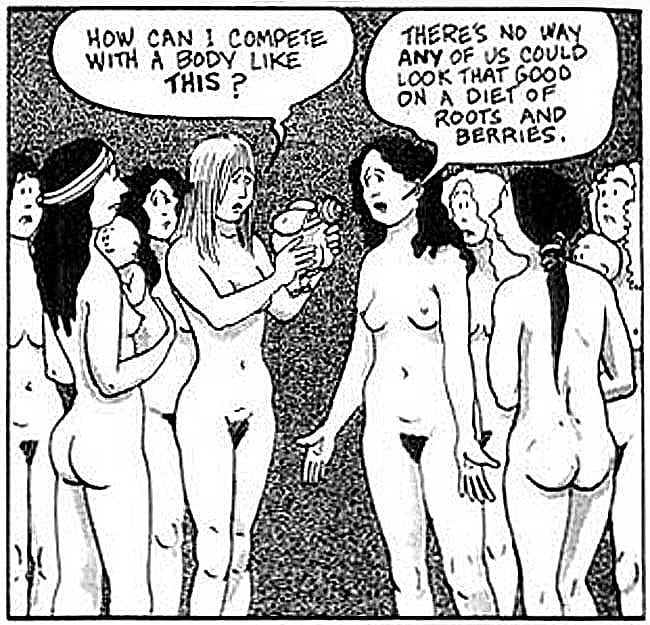

FLENNIKEN: It was for a piece I did for Lampoon called “Cave of the Bare Clan.” Did you like that? I really liked that. I’ll probably always be happy with that.

BOYD: That was a great one.

FLENNIKEN: Obviously you got it. I was afraid people weren’t going to get it … Did you see “Sperm?” “Sperm” is one of my comics that I’d love to make a scary short [film] out of … Actually, Lampoon was scared to print it in the magazine. So they printed it in The Dirty Joke Book #6. It’s another one that I did that was black and white. The whole premise is about … you know those MIAs who never came back from Vietnam? And there were these rumors about some incredible venereal disease that had been planted among the population there — the military population … I put those two together, and I had these guys — they got this disease and they stuck them on an island. And this one guy escapes from the island and goes to San Francisco. And the killer VD goes with him … he screws the last hippy chick in San Francisco, and she has this … well, you’ll just have to read it. I don’t usually show these to guys …

BOYD: Why not?

FLENNIKEN: ’Cause they’re pretty raunchy stories. They’re pretty shocking. I guess I still want people to think of me as a nice girl … [Laughter.] And I don’t think it’s going to work. I didn’t do this to ruin my own reputation.

BOYD: You might think that people are getting more prudish these days, but …

FLENNIKEN: You know what I think it is? I don’t have the kind of people around me, who do anything near the kind of work I do, who think inwardly … I think that might be it. When you talk about concepts and people just give you that blank stare … [Having similar people around is] really supportive and it really makes you want to write more stuff. You just make one little comment about something and somebody says, “Oh, right, yeah. That happens to me all the time.”

BOYD: There was a review of the Misfit Lit show in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer by a critic named Regina Hackett. She was upset by a lot of the artwork. She was especially offended by the two paintings by Carol Lay …

FLENNIKEN: I love her work! She was another person … what did she do, “Invasion of the Japanese Buzzboys?” Did you ever see those? She was another person that I wanted for the Lampoon. Carol Lay is a true talent. She gets a lot of flack, too.

BOYD: She did these gigantic paintings that were pretty in-your-face and offensive, and this critic didn’t allow herself to know that Carol Lay was a person who is known to anybody who reads comics as a satirist and an ironist, and allowed herself to be offended by these paintings because of their images. She actually called that kind of art “the seedbed of fascism.”

FLENNIKEN: I wonder what Carol’s going to think of that? She’s probably going to be real amused … she’ll probably have T-shirts made up.

BOYD: Obviously, there are a lot of thick-headed people who can’t understand satire when they see it. That’s part of the point of satire — to do a fast one on thick-headed people. And [Hackett] was certainly one of them. Plus, I think she went into the show with a bias against putting comics up on the gallery walls. She didn’t really know what she was looking at, wasn’t familiar with it, and didn’t spend much time trying to find out.

FLENNIKEN: The kind of people who like that stuff are almost a real type; you know if they’re going to like that stuff. They’re going to be real open-minded, intelligent … I guess it’s not all limited to that.

BOYD: I’m sure there are people who like that stuff for all the wrong reasons …

FLENNIKEN: Right, all those prisoner types, the career criminals. My Nazi friend … But the intelligent people who like it have a good attitude towards life in general.

THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE

BOYD: Let me ask one last question … This is one you almost didn’t answer before. What’s your current plan? Or is there one?

FLENNIKEN: My current plan? I’m doing a strip for Fershid Bharrucha for Comics USA, or some publication that he’s doing. I can’t believe it; I’m actually sitting in Seattle doing an original comic strip for somebody in Paris, while everyone that I know is moving to Paris. I’m lined up to do some illustrations for a publication called Savant Woman. It’s a whole new line of magazines that are dedicated to the concept that people don’t have enough time to read any more, so they’re short, condensed … they’re going to be a modern Reader’s Digest. I like the person whose project it is, and who knows what women with briefcases these days are doing with their time … I know I used to carry little magazines on subways, because they’d fit in my pocket, or my purse. Reader’s Digest or my favorite religious magazine, Guideposts. [Laughter.] It feels like I’ve been cleaning house for two years. My mother died fairly suddenly, and I’ve been responsible for sorting out about 50 years of family clutter in this house. It’s neat stuff, like I found a little book of matches from WWII that say “Strike ’Em Dead” on the cover and on the inside all the matches are little Emperor Hirohitos. But you have to sift through a lot of junk to find the treasures.I was so happy to leave New York. I’d wake up every day there thinking, “God, please don’t let me die here.” I guess I never adjusted. Now I can think about doing the kind of projects that I couldn’t afford to do there. Movie scripts on spec and more writing … My second marriage has ended. The last few years have been pretty stressful, and I’m looking forward to a long, cozy winter at the drawing board and the computer. It’s kind of ironic, but I ended up working with Dan O’Neill again. He was doing that War News thing during the Gulf War, and I did a strip for that. There’s nothing quite like that old underground paper buzz. •