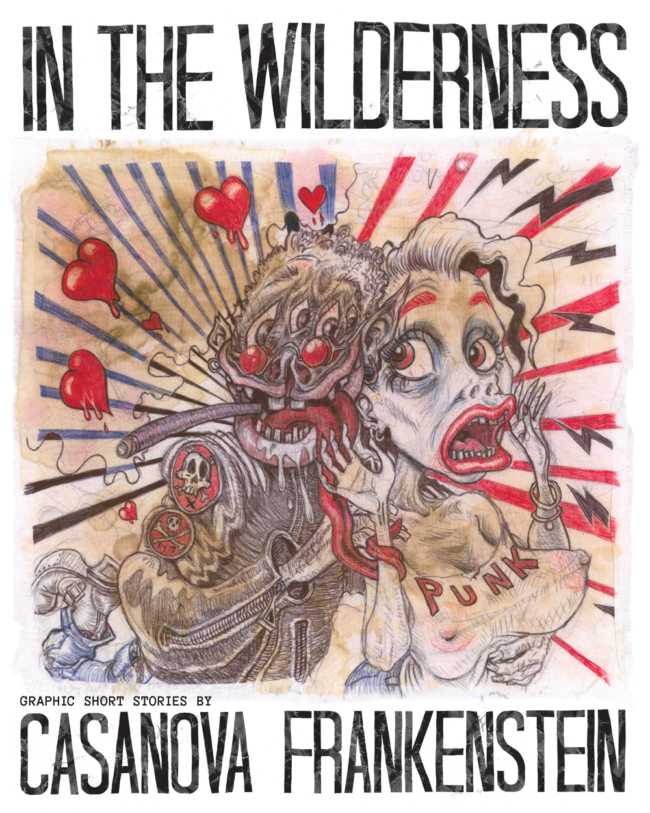

I can’t think of another one-page story – and I’m a guy who’s read The Complete Lydia Davis – with more concentrated truth or – okay, queasy-making – laughs than “Why Comics Are Better Than Films,” on page 2 of Casanova Frankenstein’s In the Wilderness”(FU Press. 2019).

I can’t think of another one-page story – and I’m a guy who’s read The Complete Lydia Davis – with more concentrated truth or – okay, queasy-making – laughs than “Why Comics Are Better Than Films,” on page 2 of Casanova Frankenstein’s In the Wilderness”(FU Press. 2019).

Here’s the thesis, delivered by a single character roughly resembling the author, in nine panels straight to the viewer. In a movie, bite off a dog’s penis, or lick the seat of a filthy toilet bowl, or fling a baby against a wall, you catch flak from an animal rights group, or risk fatal disease, or get busted for snuffing an infant. But in comics... ART!

Frankenstein not only stakes out his own claim to defiance. He provides cover for an entire coven of transgressive cartoonists, while perhaps suggesting that simply committing to paper a panel or two of a puppy mutilating, outhouse schlurping, brain-bashed newborn with nothing more – no humor, no thought, no context – is not enough – is not, in fact, any longer necessary.

Then he forgets about it and gets on with his book, a collection of bruising, lacerating, autobiographical short stories, one to 19 pages long, covering his life from ages 12 to 30. (Even though the behavior which shaped him was, by ordinary measure, abominable judged by the standard set in “Why Comics...,” you can relax. It is practically cozy.)[1] The prose is precise and penetrating, the drawing rough but compelling. All except the final story, “Temporary Insanity,” were composed freehand, in ball point pen, in notebooks secreted in pockets sewn inside a vest or in a customized shoulder holster, while “tweaking on trucker speed” at one of the minimum-wage, mind-numbing jobs with which Frankenstein supported himself for three decades.

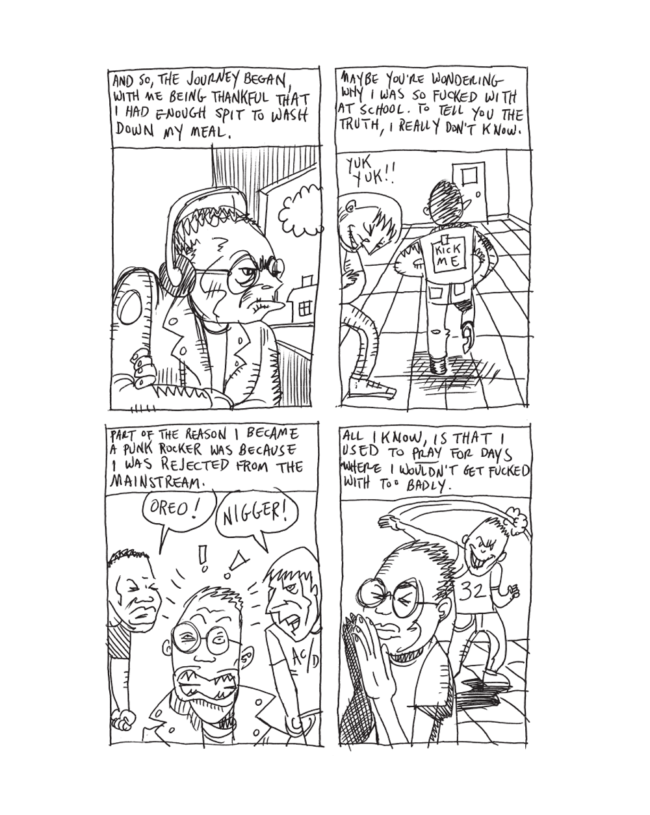

Albert Frank[2] was born in 1967 on Chicago’s Southeast Side, the only child of a physically and mentally abusive Chicago policeman and an emotionally frozen mother. Five-foot-five, uncoordinated, nerdy, he was bullied and taunted by classmates, white (“Nigger”) and black (“Oreo”) alike. He found solace in horror movies and comics, where the “justice” meted out looked good in comparison to his own life which lacked any. He became “Weird Al.”

Albert Frank[2] was born in 1967 on Chicago’s Southeast Side, the only child of a physically and mentally abusive Chicago policeman and an emotionally frozen mother. Five-foot-five, uncoordinated, nerdy, he was bullied and taunted by classmates, white (“Nigger”) and black (“Oreo”) alike. He found solace in horror movies and comics, where the “justice” meted out looked good in comparison to his own life which lacked any. He became “Weird Al.”

He had drawn since he was three. He had studied art’s “how-to”s since he was eight. It won him a scholarship to Texas Tech, in Lubbock, where he majored in drawing, with minors in photography and creative writing. He graduated with a BFA in 1991. By then he had become – black leather jacketed, with dark shades, tattooed – the only black punk in town. He had, he told his editor/publisher Gary Groth, in a forthright, startling back-of-the-book interview, found in Punk a “family,” “abused, damaged, self-destructive angels,” providing the “love” he’d sought since childhood. But “No on (knew)... what to make of me.” He was now “Black Al.”

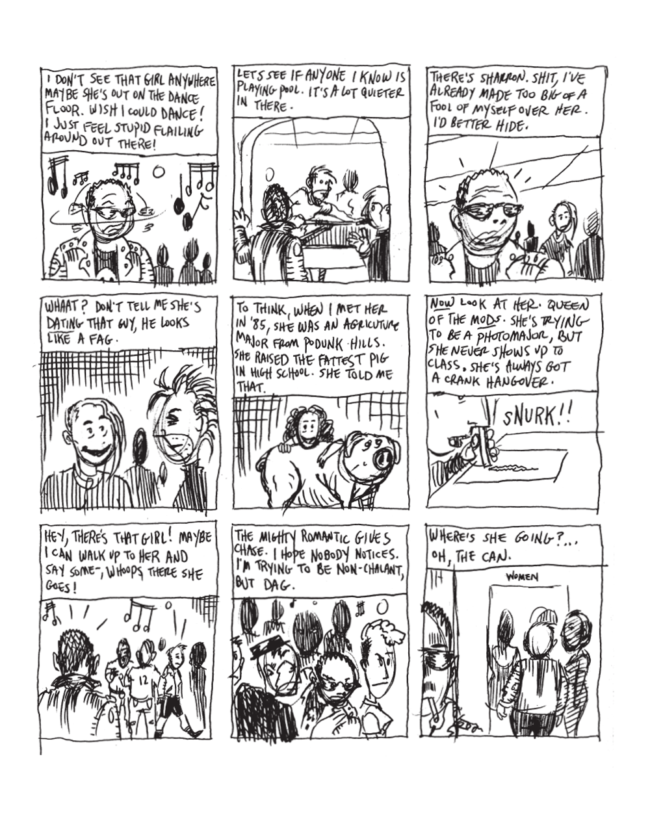

Through these stories, “Al,” “Weird” or “Black,” longs for a relationship. But attractive, if eccentric, black girls prefer white guys. Ugly black girls laugh at him. And attractive white girls behave as though he does not exist. Any girl who will have him, he disparages for her looks or infidelities or mental state, a despairing Groucho Marx declining membership in clubs that will accept his membership. “What the hell is wrong with me?” he writes in his book. He considers himself “good looking, smart, well spoken, funny,” “generous, loving, understanding,” “the perfect boyfriend.” He feels “helpless, alone and weak,” “afraid of everyone and everything.”

Through these stories, “Al,” “Weird” or “Black,” longs for a relationship. But attractive, if eccentric, black girls prefer white guys. Ugly black girls laugh at him. And attractive white girls behave as though he does not exist. Any girl who will have him, he disparages for her looks or infidelities or mental state, a despairing Groucho Marx declining membership in clubs that will accept his membership. “What the hell is wrong with me?” he writes in his book. He considers himself “good looking, smart, well spoken, funny,” “generous, loving, understanding,” “the perfect boyfriend.” He feels “helpless, alone and weak,” “afraid of everyone and everything.”

Frankenstein had already covered his junior high and high school experiences two-years ago in “Purgatory” , a mini-book (four-by-six-inch), 39-pages of text, each illustrated by a single facing drawing.[3] Even before then, in the late 80's and mid-‘90s, he had hideously re-imagined and lain out for examination most of his life in pulsating, bleeding images and prose, like entrails double-scooped from a belly wound, in a series of comic stories and books, raw, violent, nihilistic, sexually perverse, calling for consciousness obliteration and self-destruction, black ink slashing across his panels like straight razors, through an anti-heroic-to-the-point-of-psychosis alter ego named “Tad Martin.”

That this had not exhausted the subject for Frankenstein – that these were the tortures with which he occupied himself as he crossed and recrossed his employers’ floors and which he has again brought to light is a reminder of the stones lain upon us when young, from whose entombment we struggle to climb free our entire lives. “This is what shaped and gifted and robbed him,” the social psychologist Ruth Delhi says. “He could relate these experiences to the world – the treatment of the poor by the rich – the treatment of the planet by us all – if he was interested in the world; but he doesn’t extend outward from his own environment. And this is his artistic choice.”

That this had not exhausted the subject for Frankenstein – that these were the tortures with which he occupied himself as he crossed and recrossed his employers’ floors and which he has again brought to light is a reminder of the stones lain upon us when young, from whose entombment we struggle to climb free our entire lives. “This is what shaped and gifted and robbed him,” the social psychologist Ruth Delhi says. “He could relate these experiences to the world – the treatment of the poor by the rich – the treatment of the planet by us all – if he was interested in the world; but he doesn’t extend outward from his own environment. And this is his artistic choice.”

Comics, Frankenstein told Groth, were the only thing he had “passion and... aptitude for” and which, at least in their underground/alternative form, allowed expression of the emotions, impulses and attitude that writhed within him. He had, he said, followed Louis-Ferdinand Celine’s directive to the effect that “the most important thing is not to forget, but to record the shittiness you’ve seen.... (I)f you don’t record the horrors, then those experience served no purpose. To forget... was to reduce them to sadomasochistic follies.”

But after “Martin,” Frankenstein quit comics. He wrote poetry and short stories. He painted, made dolls, jewelry, walking sticks, “pimped out” leather jackets. He worked as a dog catcher, delivery driver, warehouseman, laborer, substitute teacher, stock clerk, telemarketer, security guard, cab driver, in customer service and on assembly lines. He moved from Lubbock to Austin, to Chicago, back to Austin, to Jackson, Mississippi, and back to Austin again, where he has been since 2004. En route, he had two nervous breakdowns. He married twice – for two years to a coke head to whom he proposed to on-line without having seen her and, for four, to a woman he characterized as a physically impaired, mentally ill, drug-addicted prostitute, when he returned to comics in 2015 with “The Adventures of Tad Martin, Sick, Sick, Six.”[4]

Since this return, besides “Purgatory,” Frankenstein has published “The Adventures of Tad Martin Omnibus,” a hard-cover, coffee table-sized – (But be careful whom you have over for this coffee) – 258-page collection of his earlier hard-to-come-by comix and stories, and a wordless, 11-inch-by-17-inch, tape-bound, 36-page portfolio on heavy paper stock, “The Adventures of Tad Martin Super-Secret Special,” which depicts his doppelganger’s wordless trek through hallucinatory, demonic nightclubs. alleys and graveyards. The emotional weight within these two volumes shake the jungle’s floor. The intensity of the vision makes cliffs quiver. The soul’s shrieks cloud the air.

Since this return, besides “Purgatory,” Frankenstein has published “The Adventures of Tad Martin Omnibus,” a hard-cover, coffee table-sized – (But be careful whom you have over for this coffee) – 258-page collection of his earlier hard-to-come-by comix and stories, and a wordless, 11-inch-by-17-inch, tape-bound, 36-page portfolio on heavy paper stock, “The Adventures of Tad Martin Super-Secret Special,” which depicts his doppelganger’s wordless trek through hallucinatory, demonic nightclubs. alleys and graveyards. The emotional weight within these two volumes shake the jungle’s floor. The intensity of the vision makes cliffs quiver. The soul’s shrieks cloud the air.

“Wilderness” works best in conjunction with Groth’s interview. Since the stories end nearly 20 years ago, knowing the facts of Frankenstein’s life until then – and what he has been through since –enhance the experience of reading them. (If you have the inclination and patience to make a timeline of what-happened-when to Frankenstein to measure against the stories, most of which are dated by their year of occurrence, even better.) To see the interplay between creator’s life and creative work is fascinating.

A major take away from the interview is Frankenstein’s devotion to his work, which he has both weaponized for vengeance and taken to, hermit crab-like, for protection. He lives alone in a sparsely furnished studio apartment. He has few friends. (He sheds them, he says, “like dead skin cells.”) He seems to have, at least temporarily, given up on women. He has eliminated anything which would interfere with his art, which he regards as “sacred.” He will not distract himself with the ass-kissing of commerce. He does not “give a shit about the nonsense and niceties that create economic success. I’d rather just have peace and quiet than... pretending that fucked up shit ain’t fucked up just to make my cheese.”

The final page of “In the Wilderness” is a full-color photograph of the author, shirtless, sleepy-eyed, head aslant, eying us eying him. Dreadlocks fall below his navel. Tattoos lace his arms. His chest bares a large, cracked, flaming heart. His right arm has three bracelets, leather, copper. He holds a walking stick, taller than himself, adorned with leather wraps, brightly colored yarn, a human skull sporting silver-rimmed glasses, opaque and round-lensed.

It is a lot to take in. We can sense what he thinks of us, as, even after shutting the book, we must calibrate what we think of him. To have reached this photograph, we have learned much about what went into its subject’s creation. As species evolve over centuries, so do individuals over less. So why, I think, shifting my gaze, is the man across from me in the café carrying a vacuum cleaner? Why did that fellow the other day enter with a Richard Nixon mask atop his head? Why does the hefty woman seek solution in a Rubik’s Cube?

Why, in fact, do I – with four bracelets but no tattoos – sit here in observation and judgment? All of us, briefly sharing this place, hanging on, buffeted.

Why, in fact, do I – with four bracelets but no tattoos – sit here in observation and judgment? All of us, briefly sharing this place, hanging on, buffeted.

[1]. Recollections of earlier years are infrequent but strike like nails through thumbs. Frankenstein realized, for instance, life was “futile” when he was eight.

[2]. While he had been using it for years, he only legally changed his name to “Casanova Nobody Frankenstein” in 2013.

[3]. See: Levin. “Alone.” www.tcj.com July 31, 2017.

[4]. See: Levin. “The Wild One is Thirty-eight.” www.tcj.com June 5, 2015.