S. Clay Wilson passed away on February 7th, 2021 from complications related to previously inflicted injuries. His death was initially announced on Facebook and later confirmed by those close to him.

S. Clay Wilson might well be knocking back shots in Hell with the Checkered Demon and his cohorts, the monsters and zombies and miscreants who populated his stories: Crank Collingswood, Star-Eyed Stella, Lester Gass, the Corpse Gobblin’ Ogre, the Felching Vampires, the Hog Ridin’ Fools, that ugly horn toad who always had his tongue up his nose, all ready to raise another glass to their cartoonist creator, with a barstool of honor saved just for him. He’s been dry for a decade or more, so he might hoist a few in the afterlife.

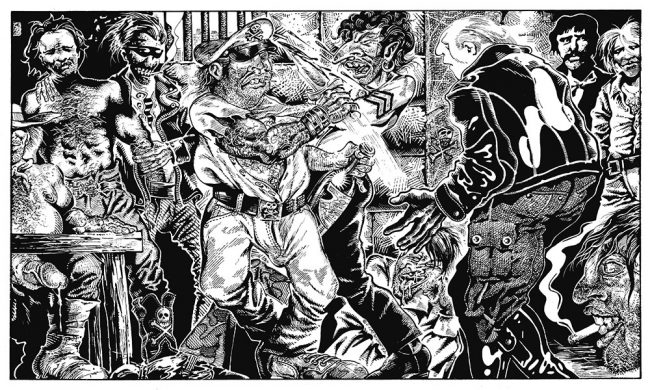

Wilson’s unique artwork went further than any of his predecessors in art history in depicting sexual deviation, mutilation, torture, demonology, vampirism, religious and racial iconoclasm and perversities of every stripe — awash with gallows humor and a sense of outrage. Painters from the past who have tilled similar ground include Édouard-Henri Avril, Federico Zuccaro, Félicien Rops, Franz von Bayros and Matthias Grünewald, but Wilson, born in 20th-century America, could express himself in print without risk of being beheaded or burned at the stake or tossed into a dungeon to rot. He outdid them all in quantity and audacity, and forged a new direction in art’s evolution. He insisted on drawing anything he could imagine in his fevered inner landscape, which was an unpredictable territory. Not only did he advance in his own mastery of his medium over 50 years of prodigious output, but he freed up others who didn’t realize they were censoring their own work until they saw what he dared to draw. He was the cartoonist you either loved or hated — but you couldn’t forget him.

Wilson chronicled a decadent vision of Americana with minimal words and maximum mayhem. His comic stories started in the throes of chaos and carnage and escalated from there. His paintings and watercolors crystallized frozen moments of absurd horror and fiendish delight that celebrated the exuberance of life even while it portrayed death and destruction.

Wilson was born on July 25th, 1941, raised in the Midwest and liked to call himself a Nebraska farm boy, but his home was in the city of Lincoln, where his father worked as a master machinist and his mother as a medical stenographer. According to Wilson, he began to draw at an early age, after a conversation with his mom: “‘When are we going to get a TV?’ She says, ‘Draw your own pictures,’ and threw me a crayon. I’ve been drawing ever since.”

In his teens, he produced a series that became more than 1,0000 single-page strips featuring his own cast of characters on typing paper his mother brought home from work. Day after day, he drew with pencil on both sides, a title page on the front and a self-contained comic story on the back. There was Kipton, Space Hero; Percy Puss and George the Dog; Detectives George and Sam McQune; Muzzy the Cabin Boy; and a pair of bloodsucking brothers, Ivan and Egor, who eventually morphed into his most famous character in the underground, The Checkered Demon. The pages flew from his hands like “autumn leaves,” recalled Wilson, who archived them in a footlocker and years later dubbed them the “Dead Sea Scrolls.” They prefigured his artistic career with recurring themes of conflict and betrayal, a preference for horizontal composition, humor in the midst of the carnage, expressive sound effects and imaginative lettering — everything but girls.

“I didn’t know any girls to draw,” he later admitted. “So, it was just men being evil to men. Of course, everybody is real horny when your sap is rising. I just took it out in having people kill each other. There were no women in them at all. That came later: after I got my first Harley.”

His college years at the University of Nebraska were often frustrating. The art department espoused abstract art and disparaged his figurative work. Nevertheless, he filled sketchbooks and covered large canvases with cowboys and pirates and bikers and swarthy foreigners. One of his instructors painted over some of his canvases so another student could use them to make “real paintings.” His notorious house on B Street became party central for the art crowd and a crash pad for transcontinental bohemians, including poets Alan Ginsberg and Gregory Corso.

Wilson moved to the Big Apple in 1965, where he found a cheap apartment on Ludlow Street, dropped acid for the first time and discovered the earliest underground comix in the East Village Other. Wilson found a job splitting cowhides at a glove factory, which earned him enough money for rent and board or beer — but not both.

His next base of operations was Lawrence, Kansas, where he immersed himself in the newly emerging counterculture spreading across the prairie states. He painted and drew, cruised the open roads on his Harley, and earned a little money modeling for the figure drawing classes at Kansas University.

He yearned for artistic recognition and the camaraderie of like-minded visionaries and dreamed of being a pirate on the Barbary Coast. Beat poet Charles Plymell offered to publish Wilson’s signature “dense pack” drawings, first in Grist magazine and then as an art portfolio of twenty drawings in 1967. Wilson relocated to San Francisco in February 1968, and dropped in at Plymell’s Post Street print shop to witness pages of Zap Comics coming off the press, watched over by Don Donahue, who later took him to meet Robert Crumb. Within a year, he became a counterculture celebrity, his “Hog Ridin’ Fools” and “Captain Pissgums and His Pervert Pirates” stories blowing minds around the globe. “I was never quite the same after meeting Wilson,” said Crumb. “I no longer saw any reason to hold back my own depraved id in my work.”

Wilson’s reputation and output grew exponentially in the 1970s, and he became known as the boldest, baddest cartoonist of the underground movement. He set his own terms and showed no mercy, defying every attempt at censorship, sharpening his chops, and creating an extensive body of work that will defy authority and offend propriety until the end of days. “My idea was not to entertain them but to enlighten them,” he declared. “Or to make them sick. One or the other. Sometimes it happens simultaneously.”

Wilson didn’t like to talk much about his work. He believed it should speak for itself without the filter of a critic or interpreter. He preferred the visual onslaught of his detailed and bizarre single paneled dense packs, which must be studied carefully to decipher the implied narrative. A magnifying glass reveals even more gory or sordid details, and even the titles are confrontational.

Wilson added watercolors and other media to his pen and ink repertoire after the underground era and expanded his audience through book illustrations, album covers, silkscreen prints, cartoons for men’s magazines, obscure punk zines, foreign comic albums and appearances at comic conventions, where he sold much of his original art.

His scandalous compositions were featured in exhibits at the Whitney Museum, Corcoran Gallery, LA County Museum of Art and many other “art with a capital A” outlets. His openings were well-attended by art patrons and critics, as well as happy hookers, tattooed bikers, Mohawked punks and infamous celebrities. At a Museum of the Surreal and Fantastique solo show in 1981, The Rolling Stones were kept waiting at the door because the place was too overcrowded to squeeze them in.

Wilson always found ways to hustle his art, supporting himself in frugal luxury for over fifty years. He was proud of the fact that he was always a full-time artist … and when the work was done, a serious drinker. Much of his output during his final productive years was commissions for private collectors, money upfront.

Wilson suffered a head injury on the night of November 1, 2008, while weaving his way home in a rainstorm. He was discovered lying between parked cars on Landers Street, just a block from his home. He slowly recovered at San Francisco General Hospital but the brain damage was acute and his mental and physical condition deteriorated from that day forward, and soon he could no longer draw or function at full capacity. His longtime love, Lorraine Chamberlain, married him in 2010 and cared for him at home until he died.

His work was published in several books, including The Collected Checkered Demon from Last Gasp in 1998, The Art of S. Clay Wilson by Ten Speed Press in 2006, and in three volumes of The Mythology of S. Clay Wilson from Fantagraphics Books in 2014, 2015, and 2017.

Details regarding memorials to Wilson will be posted here as they are made available.

Featured photo courtesy of Rebecca Gwyn Wilson, c. 1998