With three films in nearly as many years, Bone Tomahawk, Brawl in Cellblock 99, and Dragged Across Concrete, S. Craig Zahler announced himself as a filmmaking force to be reckoned with. Instead of fighting limitations (internal or external) he embraces them and sets up parameters to fight against the greatest enemy of the creative mind: Time. With his main weapon—a nigh-inhuman, rigorous daily schedule—he appears to be winning. Over 50 scripts written, eight novels written, nine full-length albums of music, and three movies are the result. Now he’s chosen to marshal his substantial creative energies on a new territory: Comics.

With three films in nearly as many years, Bone Tomahawk, Brawl in Cellblock 99, and Dragged Across Concrete, S. Craig Zahler announced himself as a filmmaking force to be reckoned with. Instead of fighting limitations (internal or external) he embraces them and sets up parameters to fight against the greatest enemy of the creative mind: Time. With his main weapon—a nigh-inhuman, rigorous daily schedule—he appears to be winning. Over 50 scripts written, eight novels written, nine full-length albums of music, and three movies are the result. Now he’s chosen to marshal his substantial creative energies on a new territory: Comics.

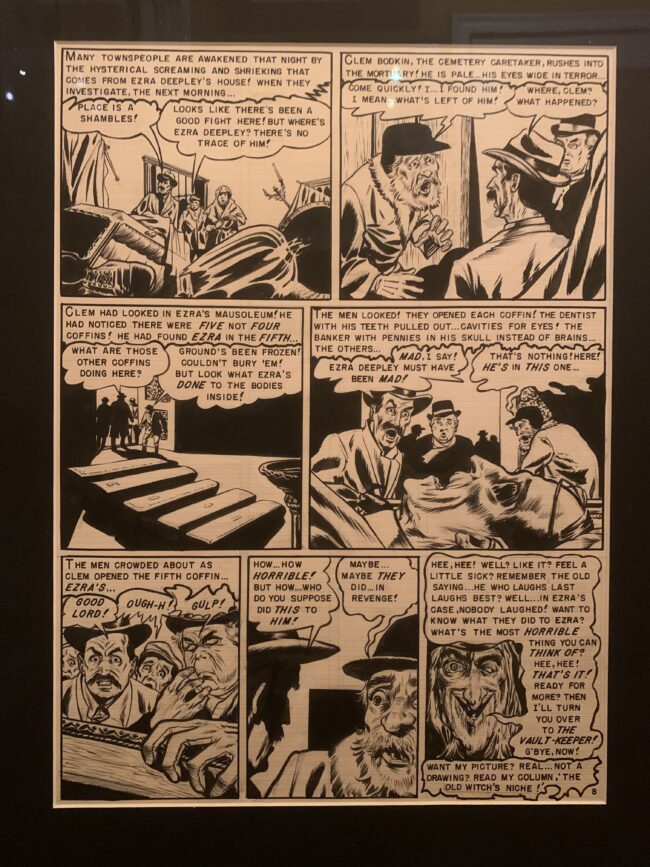

I met Zahler just before he started production on Brawl in Cellblock 99 when a mutual friend thought our interests aligned. It was true and we’ve stayed in touch over the years. When I learned he was working on a graphic novel I was excited to read it. As a first effort, Forbidden Surgeries of the Hideous Dr. Divinus is a stellar work.Zahler’s storytelling is as competent as any professional cartoonist. His panel-to-panel transitions are clear. His character designs are singular and recognizable. The beats of the story hit with the appropriate impact. Writing and directing movies is a good school for making comics. And it’s clear Zahler’s intent with his cartooning is pure given the massive discrepancy in earnings in the areas of movies and comics. He’s not making comics to make any money. He’s doing it out of total creative compulsion.

Forbidden Surgeries of the Hideous Dr. Divinus is now available for pre-order:

Benjamin Marra: I'm going to identify your book first off as both comic book and graphic novel, use both those terms interchangeably, switching back and forth just because sometimes comic book works better and sometimes graphic novel works better. But just for the record, I hate the term graphic novel, but sometimes this is the best term to use. Next, I'm going to focus mostly on your formal aspects of creating the comic or graphic novel because that's something that's super interesting to me and I want to find out more about that.

Benjamin Marra: I'm going to identify your book first off as both comic book and graphic novel, use both those terms interchangeably, switching back and forth just because sometimes comic book works better and sometimes graphic novel works better. But just for the record, I hate the term graphic novel, but sometimes this is the best term to use. Next, I'm going to focus mostly on your formal aspects of creating the comic or graphic novel because that's something that's super interesting to me and I want to find out more about that.

S. Craig Zahler: That sounds cool. I have a weird relationship with the term graphic novel as well. Initially, I remember hearing it and I felt like people were trying to legitimize comic books with this term or differentiate it from comic books because some people felt weird reading comic books, which they thought were for kids. To me, there's always a little bit of pretentiousness attached to the term “graphic novel.”

Yeah.

But at the same time, comic book is a shitty term to insofar as the word comic brings comedy to my mind.

Right.

So I think we started out with a misnomer and then replaced it with one that feels self-important. Neither are great. I just read the new Seth book, Clyde Fans, which he called a “picture novel,” and that term’s not going down any easier.

No. No, not at all. I haven't heard “picture novel” before, but that doesn't seem to work either.

You can refer to Forbidden Surgeries of the Hideous Dr. Divinus with whatever term you want. I've accepted “graphic novel” because the piece is not a floppy 23 page comic loaded with ads for Sea Monkeys and how to get stronger.

Yeah. I always equate the comic book with a floppy pamphlet serialized issue, not a long form complete story.

Right.

My first question is you're a successful screenwriter and accomplished director, novelist and musician; why did you want to make a graphic novel?

The first thing that I was ever interested in doing artistically was drawing. When I was a kid, I drew a lot. When I watched a cartoon in a certain style, particularly the Ralph Bakshi/John Kricfalusi, Mighty Mouse or Voltron or Speed Racer, I wanted to draw stories in those styles. But although I drew a lot as a kid, I was never happy with the stuff that I made.

I got seriously into comics when I was 12-13, though prior to that I’d read a bunch of things I got from newsstands—Al’s News in Miami. I was very excited to see Spider-Man in a new black suit, and that Punisher guy seemed to have a lot of large guns. So I got all of that sort of stuff and lots of different Conans. I would always try to draw in the style of whatever I enjoyed at that time as well, though I still wasn’t happy with my work.

At the end of high school, I got some advanced placement college credit with my art portfolio and was getting a little better with some things in terms of drawing. And when I went to film school (Tisch at NYU), one of my focuses was animation, though I was only interested in doing hand-drawn stuff and stop-motion work. But at a certain point, my focus became more on cinematography and directing rather than any kind of illustration.

I followed animation and comics as a fan, always maintaining an interest in hand drawn storytelling. There are times when I read comics more frequently or less frequently, but always, I had that interest. It felt like one of the things I wanted to do at some point, though it required a different skillset that I hadn't developed for a very, very long time.

I sent you pictures of a couple of pieces of artwork I have in my apartment. When I got my deal with Warner Brothers—a three picture deal for the Western script, The Brigands of Rattleborge—I went out and I bought a page of original art from The Watchmen, a Dave Gibbons page.

Wow.

I bought a Darwyn Cooke page from New Frontiers, John Romita Jr., Graham Ingels, and Hal Foster pieces when I sold other scripts or made movies, and I can mark different points of success in my career in this way. When I sold my spec The Big Stone Grid, I purchased two pages from Lint (Acme Novelty Library 20) by Chris Ware.

It is telling that the rewards for different successes I’ve had as a screenwriter, director, musician, and novelist were pieces of original comic art. Mixed up with all of this was my interest in animation, which is certainly equal to my interest in comics, and I have plenty of original cels in my collection as well—in particular, a lot of Richard Williams stuff.

To address your question, I want to actively pursue almost everything that I have a strong interest in. I'm very into food, and I made a living working as a catering chef for almost a decade. That was my day job. I'm interested in music, particularly soul, progressive rock, and heavy metal, and I've written and performed metal and soul. I'm interested in books, and I write novels, I'm interested in movies, and I make those. Comics are something I am very interested, but had not done until this book.

You and I had had a conversation, and this was... When was this? Two and a half years ago, three years ago, somewhere in there because (producer) John Schoenfelder put us in touch with one another when I was trying to get a hand-drawn animated movie going. I had a giant fantasy idea, and I’d discussed it with him and some other producers and they said maybe the idea of doing it as a comic book first would be the way to go.

But I soon realized it wouldn’t be as satisfying for me to hand off the story to a talented artist, such as yourself, even though you can do a far, far better job. That wouldn't be as satisfying to me as actually just doing it myself and continuing to develop this skillset I had when I was younger, but hadn't matured in a long, long time. Compared to my skills as a writer or a songwriter or a drummer or director or a cinematographer, my drawing abilities are far inferior, but the only way I would get better at drawing was to do it a lot.

Something I'm much better at as an adult in my forties is putting parameters on how long I'll spend on something and accepting that this is the best I'll get.

When I would leave the set from Bone Tomahawk every day, I’d say to the guy who was driving me thing like “I got 70% what I wanted to get,” or another day “I got 90%,” or on bad day, “60%.” But I knew I had to finish shooting in the time that's given and make something coherent. The discipline that's developed on a movie set and the discipline that's developed in a studio with a finite amount of time to get your performance are the disciplines I needed to apply to my first comic.

I knew I wasn’t going to love the way it looked at the end, and probably halfway through the piece, I’d look at some of the earlier pages and say, "These need to be redrawn," but the important thing was for me to say, "I'm going to spend X amount of time doing this comic to get it done."

So that was obviously a long answer.

[Marra Laughs]

I apologize ahead of time that my answers will be long.

Before I make a new piece in any medium or genre, I often go into overdrive learning about its history. Before I wrote my first western, I had just attended a film festival at Film Forum and seen 17, 18, 19 westerns in a very short period of time on the big screen and from that experience, I learned what I wanted to do differently with the genre and also the tropes and iconic things that I wanted to embrace. The same thing happened with comics when I was reading across its history from the 1920s up until stuff that had been published that year.

Right on. All right. Now, you've given me all these other questions that I want to ask you now, but I'm going to jump around a little bit. I want to go back to something that you just touched on where you mentioned redrawing earlier pages. Did you actually do that? How much editing did you do to your book after you were done with it or while you were working on it? Did you do a lot of editing?

I redrew some pages and panels, but I actually do not know exactly how you would define “editing” for a comic. The process for me doing this piece was to first write a story I believed in. I tried not to think about how I would be able to draw certain things as I wrote and just trusted in my abilities as a writer. At that point, I’d written 51, 52 screenplays and eight novels.

I hadn't drawn very much for about 15 years, excepting a handful of times when I drew and digitally painted the album covers for my metal band, Realmbuilder. I knew I needed the practice. What I first drew were rough pencil pages that were probably way, way too detailed to be called... What is it? Thumbnails? What's the term there?

Yeah, thumbnails or layouts.

So I did detailed pencil pages on blank typewriter paper. And these page are where I developed my style for the book. And eventually, I added the gray marker that I used as well. I did 19 pages like that, and I was able to draw two of those a day. By the time I got to pages 17 and 18, I looked at pages and said, "These would be good enough to ink," and started drawing thew real pages on 11 by 17 Bristol Board. My pencils are essentially the same as the inks you're looking at-

Right.

... I cleaned up lines and added a tiny bit of detail, but you could read the book and have a pretty similar experience if someone just took my pencils and turned them into ink digitally. It's all there in the pencils because I'm not a good enough inker to wing it at that stage.

I was fascinated when I saw an interview with you where you said how much detailing you did in ink because your work is so well rendered and detailed and precise. I assumed that every single Marra line was down in the pencils, but I know everyone works differently and that's the skillset that you've developed.

I knew that the first couple of finished Bristol Board pages I drew were not going to look so good to me by the time I finished, and I would redraw them, and I did. I didn't want the weakest pages to be the first few pages of the actual book, so I drew backwards from page 19 back to page one, and by the time I reached the first page, I'd already done the 19 practice pages plus 18 other full size, pencil and ink Bristol pages.

So the first pages that I actually did for the book were 19, then 18, then 17 and those three pages are redrawn. By the time I circled back and finished the book, I thought, "These are pretty shitty ."

Interesting.

I didn't want to start out with weak illustrations. I knew that the first page was very important in terms of making a strong impression. This concept comes from the albums I've made. We go in and work the first song until we get it to a good place. Then we continue to have this super intense experience of making the album and we get into it more. We’re hearing things differently and noticing certain patterns that we want to break and certain patterns that we want to keep. Then by the time we go back and listen to that first song we recorded, it sounds kind of weak-

Right.

... and not quite landed. That first song often requires a lot of work to get it up to speed with the rest. That's how I approached the comic.

So I don't necessarily know what you mean in terms of editing in this medium. The story was written from beginning to end as a short story. Then looked at the prose and broke it down into a thumbnail—a really crude indecipherable thumbnail I might add-

Right.

... and then I put up the Bristol board, and I'd look at things I had nearby—a John Romita Jr Spider-man page and a page of Watchmen were in the room—and I’d look these to have some idea how to approach the inking. I laid out each page, drew it, and you're reading what I drew.

Right on. You mentioned music. I know music is a really big part of your life. You write music and score your own films. Comics, being a silent medium, did music play any other role in creating the graphic novel other than sort of this is parallel to finding a balance of intensity or quality that you were seeking, a consistency throughout? Did music play any other kind of role when you were creating the graphic novel?

I look at most of what I do as storytelling—whether writing a novel, a script, a movie or drawing— but for me, music is the great abstract art form. Lyrics aren’t the main thing I connect to even when they are well done. Most abstract paintings I’ve seen I’d leave on my doorstep if someone put it there. It doesn't pull me in emotionally. Sorry Jackson Pollock-

Right.

Music was really good in terms of me learning how to set limitations. So it's sort of related to my other answer. There are all sorts of limitations, all sorts of parameters with time because I'm always doing music with somebody else, usually, with my songwriting partner and close friends for more than 30 years, Jeff Herriott. I need to accept my limitations as a singer. There are notes I cannot hit. My pitch needs a lot of coaching and correction. Fortunately, the guy who I record all this music with has perfect pitch or something extremely close to that. My drumming after three or four hours is going get sloppier. There are certain speeds at which I cannot get an even triplet or eighth notes or sixteenth notes.

So music really taught me how to accept something that's far from perfect and maybe a little bit below what I idealize, but still works and is worth hearing, even if I can't sing like Rob Halford, which I cannot, even if I can't play drums like Hellhammer or Aynsley Dunbar, which I cannot.

All of that really taught me to live within the limitations of abilities and time to deliver a finished product.

The other way that music comes into play is that I was able to listen to music all day long while I drew. This is one of the reasons that drawing this comic was a more enjoyable artistic experience than many I’ve had—particularly making a movies, which is often unpleasant.

My comic days were typically 12 hours at the drawing table, though some were 14-15. Occasionally, there was a fast day that was eight or nine, but no matter how long I was there, I listened to music the entire time.

I can't listen to music when I'm directing. I can't listen to music when I'm sitting in the editing room. I can't listen to music when I'm mixing down the movie or making other music. I can't listen to music when I write. So it was a joy to be able to listen to so much music every day while making this comic.

I went through catalogs of stuff I had with the exception of heavy metal, which I find too engaging and distracting to have on while I'm drawing. Soul music, prog rock, jazz, EDM, martial industrial—really everything that I enjoy I listened to other head-banging stuff.

Interesting.

Do you listen to music when you draw?

No, no. I mostly listen to audio books because I kind of need a narrative to engage part of my brain and distract me a little bit, so that I can find a zone of drawing, which is... I think it comes from when I grew up, I would just come home from school, watch cartoons in the afternoon, and draw. So I was constantly drawing while listening to some kind of story being told. I think that it just became sort of like a comfort zone for me. But yeah, music hasn't been something that I turn to by default. I'll have to really, really want to listen to something specific. But otherwise, if I do put on music, it will be like a dungeon synth type thing.

I would guess that I have one of the largest dungeon synth collections—physical CDs and cassettes—in New York city, if not, the single largest collection. For me, that's the greatest gaming music.

Yeah.

I can’t play board games or RPGs with music where people are singing words. To me, there's a conflict there.

Absolutely.

Dungeon synth is perfect for playing Cave Evil. Or Perdition’s Mouth: Abyssal Rift, or Runebound, or Mage Knight, or any of these fantasy-themed games.

Yeah, perfect soundtrack for that.

I'm not really a background music person, which is one of the reasons I don't have music on when I write, but when I'm drawing I can enjoy both the work and the tunes, even though I’m a terrible multitasker. I knew music was going to make this experience 10 times more pleasurable. I’d think, "Today, I'm in the mood for a lot of John Coltrane. Today, I'm in the mood for a lot of Frank Zappa. Today, I'm in the mood for Barry White and the O'Jays.”

Right, right. You mentioned board games, and I know you play RPGs as well. Do these gaming activities have any bearing on the stories that you tell or influence your storytelling in any way at all?

RPGs had a big impact on me as a writer.

I feel playing a good board game or RPG is halfway between reading good fiction and writing good fiction. I say, "good," not because every board game you play is good or every RPG session you have is good, but because I am actively engaged in the fictional world the way that I am when I’m writing.

So to me, there's that overlap, insofar as it bridges the gap between reading fiction and writing fiction. It stimulates that part of my mind.

When I was a kid, 11, 12 years old, I started getting into Dungeons and Dragons and that's how I learned how to write. Because when I was a kid, I was the Dungeon Master in probably 80% of the games I played. And people from that era, who would look back on it later and remember me killing everyone all the time, which is clearly an impulse that transfers to my books and my movies at this point in my life.

That's where I learned storytelling as a creator, because a lot of the times I was just making up the module during the game. And if you have two, three, four, five kids playing and you're running the game, someone will do something unexpected, and you need to have an answer. You need to make up the thing that happens next.

I think that skillset is one of the reasons that I've never had anything that I would consider writer's block. And to some extent I don't understand writer’s block, if a person understands the characters they're writing and understands the goals that characters are trying to achieve. Maybe it is just as fear of the story getting bad?

So RPGs are at the core of me developing my abilities as a writer. And in a good RPG, three, four, five people are writing the story together.

As an adult, I don’t run the games, but prefer to play a character instead.

RPGs figured prominently for you as well, right?

Yeah. I mean, I run a lot of RPGs for people and I found that that's the only way that I can play RPGs, is if I actually run the games. Because I love playing them so much, but a lot of the times I don't get a chance to be the player because, I don't know, it's hard to find a game. So I just figured I'll start the game myself.

And that, I've found is really satisfying in a lot of ways. And yeah, I think it sort of touches on the same sort of things that you're talking about, with the satisfaction of telling a good story or it just satisfies that aspect of my creative impulses.

Yeah. I mean, I really love RPGs. I wish I could play them more often. I wish I could play them more than once a week or more than once a month. I think they have a huge bearing on someone's ability to develop good storytelling instincts.

Because it's improv storytelling in the moment, like you said, where you have to sort of come up with some new turn or twist or element to keep the story going or keep people engaged. Yeah, it draws on a lot of those skills and it teaches a lot of those skills.

Yeah. RPGs, I think are really great ... I don't know if it's like an exercise. It's sort of like a mix between practice and entertainment, where you can develop-

That's a good way to put it. I said it’s halfway between reading good fiction and writing good fiction, but yours is another way of saying that—and perhaps a better way of saying that.

I remember doing an RPG campaign that went on for a couple of years. Some really massive Call of Cthulhu campaign, where all of our characters died at different points, and then all of our secondary characters died at later points.

There was some small event that derailed into a massive hostage situation in an opera house. This was just supposed to be a little pit stop, but we had a five hour game of a giant hostage situation that wasn’t part of the module at all.

Yeah. I mean, it's amazing how those sort of unpredictable moments can create such vivid memories, even going back a decade to recall it.

Yeah, I was going to say, even as a player, you're still contributing a lot as a storyteller because your choices as the character are influencing the story. And I mean, that's what story really is. It's just characters making choices. So, your understanding of those of those characters or the character that you're playing, requires a bit of storytelling imagination.

Oh, absolutely. I like the idea of just showing up for a game and not knowing at all where it's going to go…

You mentioned reading a ton of comics before embarking on creating this comic, your graphic novel. Can you talk about some of those comics that had particular influence or impact on you? What did you learn from your reading of these comics throughout the history of comics?

Let me not turn this into a seven hour answer.

[Marra Laughs]

First off, there are a few comics that I look at as the key stepping stones to me doing this piece. The first one is Wimbledon Green by Seth. I've read most of his stuff and that book is his crowning achievement. Have you read that book?

I haven't.

In many ways, it’s the Citizen Kane of comics. It is beautifully written. It is funny. It has mystery. It's sad, and it's engaging. At points, it's even exciting.

I think Seth drew it in his sketchbook. And there's a dismissive introduction where he said something like, "This is just stuff from my sketchbook. These drawings aren't as finished or polished as my other stuff,” and those kinds of disclaimers. And yes, it's simpler and looser than most of the iconic, cartoonish Seth artwork out there. But I think it's incredible. I think it's one of the best comics I've ever read, and I think it's definitely the single best comic that I've read that has come out in the last 20 something years. It's his writing coming through and also the simple iconic characters that he's draws that allow the reader to read into their expressions and invest it with more depth.

So, with Wimbledon Green, I saw the benefit of using simplistic art to tell a complex story. I'm not technically aware of what many artists are doing, but when I looked at the drawings in Wimbledon Green, I didn't think, "These are beyond me." I thought, "This is something I might be able to do.” I probably couldn't do it with the level of consistency he has, and I wouldn't draw mine to look like his, but I saw that there was something to be gained by this simpler abstraction of a human being, in particular, a human face.

This obviously ties to things like Peanuts and how those faces look. And to some extent, all the Donald Duck stuff I was reading at the time, particularly Carl Barks' stuff, but also Don Rosa’s and Al Taliaferro’s. All of this put in my mind the idea that, if the story is there and you find the right icons, you could make something moving and engaging.

So I put Wimbledon Green on a pedestal. And I compared it to Citizen Kane because both have an obfuscated, Baroque storytelling approach used for the mysterious biography of a morally ambiguous protagonist. And both are great.

And it was a comic book where I saw someone drawing images that wouldn't be completely beyond what I could achieve.

Right.

So that's the beginning of it. And then I immersed myself in comics history.

The EC comics I’d been reading since I was a teenager were a key influence as well in terms of content, but I knew that that art was well beyond me. I’m looking at this Graham Ingels page I have on my wall. If I spent two months of my life trying to draw this, it still wouldn't be as good as this damn Graham Ingels page. This self-awareness comes from my musical background--I just know that I can't sing those notes.

I was also reading Roy Crane stuff, his Buz Sawyer in particular. I don't want this to come off like I think I have the skillset of Roy Crane or Seth, because I don’t at all, but when I looked at Buzz Sawyer I thought that those types of icons were both powerful and achievable.

Ramping up to doing this comic, I read no fewer than 2,000 pages of Donald Duck comics. I really started to see the incredible magic of Carl Barks, in particular, how much motion you sensed on the page, and Barks’ awareness from panel to panel, of where he put the character for continuity. I don't know if the comics term is page direction—I think of it in terms of filmmaking, which is screen direction, but the consistency and layouts and figures in these Donald Duck and Scrooge McDuck comics really leapt off of the page. You just sensed motion.

And I knew that that was another advantage of a simpler style. Because when you look at a Graham Ingels page, it's not leaping off of the page in the way Carl Barks does. It's superb, but in a completely different way. More like the style of masters like Hal Foster and Frank Frazetta—the kind of illustrations where you're admiring the craftsmanship and savoring atmosphere and detail. These are all world-class artists whom I adore, but Carl Barks showed me again the pluses of simpler stuff.

Fantagraphics put out these Don Rosa Donald Duck, Scrooge McDuck books as well. And that was another key stepping stone for me because this was one of the first times I saw actual thumbnails. Have you seen these Don Rosa books?

I haven't, but I can sort of imagine what those roughs sort of look like.

Yeah, they're rough. They're not beyond almost anybody's abilities to draw, but the story was already in them. So that was another piece of the puzzle. And I adore Rosa’s more scientifically minded duck stories.

I was also reading a lot of pre-code horror beyond the well known EC material, and there's a lot of stuff out there. Some of it isn't so good, but some of it's quite good—like This Magazine is Haunted and Forbidden Worlds—and all of that figured in.

One other influence came from Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy stuff. I think that’s a more direct influence on my finished comic book than these other things that I've named because I've shown my comic to people and that's a comparison that's been made.

Gould was a master craftsman working at a skill level that I don't yet have and probably will not ever have, but his highly differentiated character designs influenced what I wanted to do.

I wanted people to understand the story and for there to be absolutely zero confusion as to who was who. I wanted characters immediately recognizable as themselves, and a more stylized and cartoonish direction facilitated that for a limited artist like myself.

For instance, I recently returned to Maus, which I hadn't read any of in a very long time. It's terrific and beautifully written, and lot of my favorite stuff is young Art Spiegelman dealing with his father, rather than the World War II stuff being recounted, things I've seen my entire life, since being a 10 year old kid in Hebrew school and watching atrocity footage films. But if I wasn't given clues with the dialogue and the prose, I wouldn’t be able to differentiate these mice. This may be by design, but I knew that I wanted my characters to be immediately recognizable and uniquely rendered.

So Chester Gould was the last real big piece of the puzzle that started with Seth's Wimbledon Green and E.C. Comics, and there's a ton of other stuff in between.

There’s also that gray marker I’m using to differentiate things in the panels, partly because I was looking at a lot of Floyd Gottfredson’s artwork. Have you ever read any of his stuff?

I haven't.

This is a Mickey Mouse guy.

Okay.

Actually, he was the main Mickey Mouse guy for something like 35 or 40 years of his life.

Oh, wow.

This gray tone I’m doing with my marker was emulating what he did in that strip. I don't know how he did it…?

Yeah, it could be zipatone that's just applied as a separate transparent sheet. It sticks right onto the artwork. Or it could be the type of board, which I don't think that came around until the '70s maybe, where you could actually put a chemical down that would bring out specific gray tone patterns that are in the board itself.

Yeah. Prior to drawing my book, I did a hunt to see if I could find some of those boards. It's probably extremely good that I didn't find any. Some of these Gottfredson stories are good, some are not good and many are sort of somewhere in between, but like Al Taliaferro, who did Donald Duck forever, he is an immaculate craftsman. When you look at the lines, it's hard to believe that a human being rendered this stuff so perfectly.

I have an Al Taliaferro Sunday page right near my Chris Ware artwork, and it's a similar level of perfection. But Taliaferro was churning out five daily strips and this gigantic Sunday strip every week for 40 years. He's not laboring over the new book for three or four years or five, or however long it takes a perfectionist like Chris Ware to do something like that. This guy was putting it out every day and it's inhumanly crisp and neat.

Yeah, effortless.

So anyway, I made a bunch of rules coming into this project and that's the same thing that I did with Bone Tomahawk. I did not have enough time to shoot that movie and I figured out a way that I could do it in the amount of time that I had. Bone Tomahawk and Brawl in Cell Block 99 were both shot with the same cinematic rules of handheld over the shoulder shots, cutting on people's looks, etc. Each scene has a protagonist and I followed that person in a medium. And then I had locked off wides that showed the environment and a different perspective.

I needed to come up with what I could achieve in the time given and it was similar with my comic. I thought, "If I get into complicated crosshatching, I'm going to mess this stuff up and I don't do it particularly well in any case. So let me figure out how I want to do shadows.”

And I knew I wanted to have another value in there other than all of these diagonal lines, which aren't really quite feathered because I did it with a rapidiograph-type pen. A lot of that was coming from really old comic strip art. And it's probably my salvation that I didn't find that paper where you dissolve layers away to get tight black lines. Have you ever worked with it?

I haven't. It's super toxic to use because you have to use these really terrible chemicals and apply them-

More good reasons for me not to come across any.

Yeah, exactly. it's hard to find and probably really expensive now, to find in any sort of abundance that you'd need for comic book work or creating over a hundred page comic. I just digitally apply any of those sort of screen tone effects. I use them in Photoshop, which is kind of a cheat, but it gets the same effect down.

Sure. I knew that I wanted everything on the page itself, and here I can draw the parallel to my filmmaking approach, where all of the special effects are done practically on set. I don't want people to see CG effects when they watch my movies. I don't know how many people this millennium are doing a scene where characters get shot by arrows and those arrows are actually being thrown on set along fishing lines at the actors. This is what I did on Bone Tomahawk because I wanted Richard Jenkins and Kurt Russell reacting to real things. The idea is if something convinces me on the set, then it's going to work for the finished movie. I prefer that over counting on creating things with CG, which looks shitty even in giant budget movies.

And I knew that I wanted the comic done that same way on the page. A couple of little smudges, white out drops, and pencil marks were cleaned out, but for this first comic I really wanted it to be 100% what I drew and for there not to be another step.

Awesome. A lot of your instincts are pretty advanced considering that is your first real comic book effort. This is your first comic, right?

Correct. In sixth grade and seventh grade, I drew some of a Mad Max comic book which is kind of funny to think about me working with Mel Gibson all these years later. I did pages where he was going around on some nitro-powered skateboard.

And I had a hero that I created named Austin Scott. I drew some pages of him fighting a cyborg named Hollowcaust who had a flamethrower arm. But I think my first thing was some terrible tracing I did as an even younger kid—Indiana Mogwai, Because I liked Gremlins and I liked Indiana Jones…so why not just bring these things together?

Yeah. Mash them up.

Other than these pages, which were obviously just a child's dabbling, I've never done any comics before this.

You’re storytelling in the comic is great. It's flawless.

Thank you very much. That's great to hear.

No, it's fantastic.

These compliments mean even more when they're from an artist who has inspired you.

[Laughs] Of course. I wouldn't say it otherwise, because it's true. That's obviously one of the biggest hurdles for people who are just starting to make comics, is really nailing down the storytelling. But also, recognizing that simplicity can be an advantage. I know my first instinct creating comics is put more detail in there and that makes it “better” you think. But simplicity actually makes things clearer and more readable and, like you said, it makes things move across the page a lot more effectively.

Also, understanding that characters need to be read as that specific character at a glance. Recognizable right off the bat, which all of the characters do that. I think that they all have different silhouettes which is one of the key ways ... it's the best way to judge if characters are different enough is if you can recognize them as a silhouette.

Where do you think all of your instincts developed from? Is this from your animation background? Is this from just writing a ton and visualizing how stories will unfold? Envisioning these stories. Does it come from actually shooting movies? Understanding how to block a scene, or where do these instincts that you developed and applied in this comic, where does it all come from do you think?

Or it could come from just reading a ton of comics like you did.

I think it comes from reading a lot of comics and the visualizing process that is my writing process. There's a reason people know that I'm a novelist when they read my screenplays. That was actually one of the first things Steven Spielberg asked me at some brief period when I had a deal at Dreamworks and came up with tons of weird ideas that they had no interest in ever making. I thank those guys for paying me well to pitch movies they would never make.

My objective with this was to tell this story. Everything was in service of that.

That does connect to the filmmaking when I'm on set with nowhere near enough time to do an ambitious project. An actor does a two-minute scene and I need to decide if I have all the little moments I need. I need to recognize what images and sounds are telling my story in the manner I want it told.

That process of filmmaking directly informs me choosing what moments I put in a comic panel. I know when beats change for the character and when his expression alters. If a guy is essentially in the same emotional state, I can put a lot of dialogue with one picture, but then sometimes I'll have two panels where there's not a lot of dialogue or none to show the emotional change, where you just watch an emotional beat change,

My ability to assess the most important or interesting moments come from moviemaking.

I knew not to try and have stunning artwork be the selling point of my piece because it was beyond me. I wanted stuff that would tell the story and get the beats right. When I go through and cut dialogue sequences in my movies, there's always a rhythm that I hear in my mind ahead of time. Don Johnson gives me these cadences how I imagined, but alters the melody some. Mel Gibson, Tory Kittles, and Kurt Russell are landing where I imagined. Vince Vaughn is coming up with his own cadences that are different than what I imagined, but they are often just as good if not better.

My sense of “Here's a line that you should hold on and here's a line that you shouldn’t” translates to comics. This became, "Do I put this line as dialogue at the bottom of a frame so you look at the face first? Do I put it at the top of a frame so you read it and then look at the face? Do I put one line at the top and one at the bottom with the face between them for a pause or a beat?

I don't know that I've seen people do this as deliberately, though I'm sure some have. I also knew I didn't ever want word balloons running into people's heads. There are cartoonists who are far, far, far, far better than I will ever be who have this happen, and sometimes it might not have been their fault if a letterer plopped it in place or a writer made some additions, but it bugs me.

Did you read any books like Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud?

I’m watching Cartoonist Kayfabe on YouTube, which instantly became my favorite thing to watch online, and I saw that they were talking about it, but no, I didn’t read it.

Almost my entire career I've stayed away from how-to book’s, partially because the person writing a how-to is giving you their opinion on why something works and why something doesn't work, whereas I'd rather form my own opinions.

That's what happened when I watched those 17 plus Westerns at Film Forum prior to writing my first story in that genre.

Some lone individual telling you how to do your art is something that I find strange. I’d rather immerse myself and draw my own conclusions.

You were trained right? Did you go to SVA? What's your background?

I went to Syracuse University for illustration. I got a BFA there and then I got an MFA in illustration from the School of Visual Arts. I was discouraged from doing comics when I was an undergrad and then in my Masters program, I got a chance to work with David Mazzucchelli. I took his comic book workshop class.

Oh, wow.

It's hard to quantify how valuable that class was to me, but I learned an immense amount from him. He also advised me on my thesis which I decided to do a comic. I had a professor David Sandlin who also makes comics and he was very encouraging to pursue comics. I had a lot of formal training. As much formal training as you can have. Although, at SVA you pretty much can major in cartooning and making comics. I didn't go that far, but I got a pretty good amount of formal training for sure.

Obviously I'm a big fan of your work. Do you feel that training was mostly beneficial? Entirely beneficial?

I would say it helped, but when I think about it, a lot of my training is just from reading comics. It's kind of like you said, you just develop instincts from the study and a deep analysis of what you care about and what you're interested in. I think just from reading comics from an early age and just picking up on the mechanics of it gradually maybe unconsciously that helped me over time.

Making comics in Mazzucchelli's class, I already knew that I had some innate, self-taught abilities there but he was able to help me refine things. Although I've been making comics seriously for 12 years now, I'm only just sort of learning that simpler drawing combined with words—just like Charles Schulz or Chester Gould—makes for the most effective comics.

I've also been looking up a lot of manga and Astro Boy or any of Tezuka's stuff. Who is sort of the Jack Kirby of Manga, maybe even bigger. Just how simple his drawings are. Coming from an illustration background, it was always my instinct to make every panel an illustration whereas comics don't work like that. Comics aren't optimum that way. If you keep the drawings more distilled ... They are simpler but they're almost not simpler. It's almost more complicated when they're really boiled down to the essential information.

That's the thing with Mazzucchelli's work in Year One. There are a fraction as many lines as there are in Dark Knight Returns, but each line has a stronger purpose. And you also read it quicker in terms of image recognition. Both books are huge inspirations for me.

I recently gone pretty deep with Tezuka’s stuff while I'm gearing up for my next one, which is on the horizon.

Astro Boy is a bit of a chore, but there's a book called Ode to Kirihito that is incredible.

The Black Jack series really stands out for me too—I would really point you towards those as well. And MW is quite good. It's long like Ode.. and it's adult.

Interesting. Yeah. I've read MW before and I read the Book of Insects. I can't remember the right title for that one.

The Book of Human Insects?

Yes. Yes. That's it.

Yeah, I have that. I've not read that one yet. How is that?

I liked that one a lot. It's in the same vein as the ones that you responded to. Yeah, definitely check it out. I'm happy to hear that you're making another comic.

On Monday I start writing it and then I'll start drawing it, and I'll probably draw it until production takes me away for the next one, though I don't have any control over when that happens. And I want to do at least three full graphic novels.

I feel that once an artist has three pieces out there, a reader or viewer of listener will have some sense of that artist’s aesthetic and identity. There’s a body of work.

I could write a novel and a screenplay or write six screenplays in that amount of time it will take to do another comic or I could shoot a movie and do most of the editing in that amount of time—

[Marra Laughs] Right.

It takes a staggering amount of time, but it’s worth it to me.

I trained to do hand-drawn animation, so the thought of doing a ton of work for a piece that someone might read in 40 minutes doesn't deter me, because with animation, you might spend five or six months of your life on something that lasts for two minutes on screen. So I'm okay with that exchange rate if that's what the medium calls for.

My first comic is this noir horror thing, and my second one will be science fiction and I'm not sure what I'll land on for the third. I’m not sure how this first one will be received, though I expect some people will say, “The story is pretty good, but this guy should hire a real artist." And that's fine. Long ago, I realized that different people are looking for different things, and nothing that I've ever done in any medium is going to appeal to everybody. Some people will like the art, others won’t, and others will cut me some slack, because it's my first comic. I have lots of criticisms for the art myself, but I’m happy I made this book and feel contains my idiosyncratic characters and storytelling voice.

That's true. And every time I am asked by somebody who says "I've got a story that, I want to turn into a comic and could I hire you?" And I always think, "Just draw it yourself," because I feel like that's the best way to get the story told. That's the purest way.

If it's a collaboration, there is usually something lost. Very often it doesn't happen that you hit this magical synthesis like a Kirby and Lee or something like that. It's usually better for the writer to just draw the story themselves, no matter what level they perceive their drafting ability to be. It never really gets easier anyway. I still struggle with the same drawing problems, I did when I was a teenager. So it never really gets easier. You're always, battling yourself. I do think that it's the way to go though, for sure. So I'm happy that you did that.

Well thank you. Because I was talking to you at some point about drawing a book for me, and a producer I worked with had a good conversation with Bill Sienkiewicz about us working together, and I’m friends with the incredibly talented Mat Brinkman, but you all make your own books and you have your own identities. And I know there would be something missing for me in terms of satisfaction as an artist if somebody else drew my comic story.

The first thing I wanted to do as an artist was draw and none of these other careers have replaced that first urge. And I know how many hours I needed to put in to get better as a writer.

I've read so much stuff since I finished drawing, and I know that different influences are going to come in the next time. More comic strip stuff, like Gasoline Alley and The Phantom, and a little bit of Moebius too. And I’ve read about 140 Jack Kirby comics in 2020. That's going to impact things some way.

The more closely I inspect things, the more I intend to change my inking style. I've now got some nib pens and I'm going to try and deal with them, though that might be a total mess for me. I assume you use a nib pen?

I do. It depends. I like the nib pens for that classic comic look, but they can be a pain to use some times.

I bought some self-filling kinds to check out and hope that they work.

I haven't used them. I have a friend who I saw was using them, and they look great. I'm suspicious though because I want to try them out. I'm suspicious that they'll be a mess. I'm curious to see how well they hold the ink, and how it flows out onto the nib. They do sound like an ideal tool. But I found that any ideal tool that I think is going to work well usually has some critical flaw.

I'll see. I know I’ll want lines to have naturally varied thickness, though that single thickness line type works for C.F.

There are some brush pens that do replicate a dip pen pretty well. I can send you some ideas for that.

Sure. I colored in all of my blacks with brush pens, but I felt like there was a bit of a wobble when I tried to do anything else with them. I type hard and the keys come off of my computers after a couple of years, and occasionally when I play drums, I go through a pair of sticks in five minutes—they’re shattered everywhere—and I’m breaking cymbals too. I have a very heavy hand with all of this stuff.

Yeah, there are ones that have like tighter nibs, like tighter points that are easier to control, that’ll have a better result. You can get a finer line with them. I'll send you some. Yeah, I'll send you a couple of links. You can check them out.

I’ll try anything you send me a link for, unless I've already tried it.

I mean, I’m reading all of this Kirby and wondering how Mike Royer gets those lines? The pencils are all there but it's just so lush and sharply defined and seems so fluid too. But it's still really precise.

I think the drawing style for my next book is going to be pretty different. This new story calls for a different look.

Do you have any interest in adapting stuff you've written before? I'm imagining that this next comic of yours is going to be a brand new story?

Yeah it’ll be brand new.

Do you want to adapt anything that you've done before this into a comic or are you just going to do completely original ideas?

I think I'm going to focus on original ideas that were conceived of with this medium in mind. Forbidden Surgeries of the Hideous Doctor Divinus was written to be a comic book. I was thinking of that pre-code horror stuff and the value of those shock panels in Junji Ito’s manga.

I wouldn't want to adapt something like a book or a script of mine that play with different visual and internal languages.

You have an insane amount of discipline and I gather that you've got pretty specific routines, you know, to maximize your productivity.

Yes.

Where did that start? How did you get and where does that come from?

A lot of that discipline comes from me highly valuing my time off. I work long days often, but I also want to enjoy and pursue all of my interests—comics, pulps, boardgames, movies, novels, NYC restaurants, music, etc. If I were laid back about how I approach any piece, it could drag on and loose momentum. That’s why I set time limits.

Also, I cannot enjoy myself fully until my day’s work it done—that’s a compulsion I have and have always had.

And I now accept that things can fall short of what I'd initially imagined and still feel the project was worth doing. I knew that this first comic was going to fall short of Chester Gould, Carl Barks, Al Feldstein, Frank Miller, and Junji Ito, but I worked hard to get my six pages done every week.

One more question: Do you feel like working on these comics is going to have any sort of impact on how you work on screenplays or are working on movies?

All of these stories are coming from the same place of me visualizing things ahead of time, but my feeling is that filmmaking will more strongly affect my comics than the other way around. This is something I’m proud of with the comic—a lot of the character reactions are low key like how I direct the performances in my movies. Even though the characters look cartoonish, their reactions aren’t very exaggerated.

That's something I see with artists who are going for a photorealistic look. Like that guy Brian Hitch—the guy who did The Ultimates?

Yes.

Realistic art like that feels like bad acting if the reactions are overdone at all.

Yeah.

So this aesthetic carries over from my movies to my comic. I favor low-key, natural performances in both in order to ground all of the violence and weirdness taking place.