Scarcely known in the U.S. but a household name and sales guarantee in Italy – that's the criminal genius of Diabolik, one of nihilistic trash comics' founding figures. In Diabolical Summer Thierry Smolderen and Alexandre Clérisse provide you with a different perspective on the masked villain. The gentleman criminal in disguise Diabolik has enjoyed great popularity since his creation in 1962 by two sisters from Italy, Angela und Luciana Giussani – at least in the country of his origin.

As Diabolical Summer writer Smolderen says in his afterword, Diabolik rose from a long tradition of anti-heroes that also spawned protagonists like Fantômas and Dr. Mabuse, but is ultimately based on Harlequin Faustus. In Diabolical Summer, made jointly with cartoonist Clérisse, Diabolik – an archetype of sinister comics cartooning called fumetti neri, which appear to be of an assembly-line and sado-pornographic character – is used as a cipher for anarchic tendencies resting in humanity, while with Harlequin Faustus, classified by Smolderen as a lineal descendant of the Commedia dell'Arte, Diabolik's geographical offspring comes full circle.

Two attempts have been made to establish Diabolik for an American readership: in 1986 via the Pacific Comics Club, and 10 years later by Scorpio Productions. Neither were crowned with success or longevity. This fate is shared by Mario Bava's beguiling and stylistically confident cinematic take on the anti-hero, entitled Danger: Diabolik, probably because of a style-over-substance attitude that is too much on the nose – even if you're one of those wayward critics who value both as interacting on equal levels.

The basic premise for all plots evolving around Diabolik is as follows: Equipped with a minimum of moral principles that do not exclude blackmail and murder, Diabolik finances his lavish lifestyle by raiding public institutions and the morally questionable. Always by his side is Eva Kant, as a helpmeet conjoined with her partner in cold precision. The very meaning of their lives is that of a perpetual rififi, metonymic with the compensation for a never shown but always latently resonating and long-yearned sexual climax within a seemingly platonic relationship. Like most fumetti neri aimed at mature readers in Italy, the artistic level is consequently one that carelessly produces slipshod art hastily cobbled together for an all-devouring mass market.

Milo Manara, by the way, also debuted in this branch of Italian comics, and the majority of his later works still shows formative influences from this exploitative genre. However, to this day the interiors of Diabolik are sparely drawn – and certainly not for artistic reasons. Interestingly, women make up the largest share of the series readership. This may be due to Angela and Luciana Giussani's initial conception giving precedence to romance, or to the involvement of long-time scribe Patricia Martinelli. In any case, the fact that it was conceived and successfully commercialized by women is noteworthy.

Milo Manara, by the way, also debuted in this branch of Italian comics, and the majority of his later works still shows formative influences from this exploitative genre. However, to this day the interiors of Diabolik are sparely drawn – and certainly not for artistic reasons. Interestingly, women make up the largest share of the series readership. This may be due to Angela and Luciana Giussani's initial conception giving precedence to romance, or to the involvement of long-time scribe Patricia Martinelli. In any case, the fact that it was conceived and successfully commercialized by women is noteworthy.

So there's an inspired realization of playful sexual intercourse amidst stolen goods in the cinematic adaption of Danger: Diabolik, whereas Clérisse and Smolderen use a mannequin who allegedly served as a role model for Eva Kant in the comics as an abstraction of the sexually open fumetti neri by letting her offensively grab a male protagonist's crotch – all of which is arranged within a scenery of features commonly associated with pop art or another cipher for loot, if you will, while the original black and white version, which is still in publication, according to the sisters Giussani remains as firmly committed to its romantic roots as Eva to her Diabolik.

Unperturbed by such matters, the subliminally infused myth developed a life of its own, as you'll recognize by looking closely at Bava's interpretation, or Smolderen and Clérisse's. Though the former lacks stringency in narration despite its visual finesse, the Franco-Belgian duo once more – after their idiosyncratically furnished biography of science-fiction writer Cordwainer Smith – proves its capability of turning unusual source material into excellent comics.

Unperturbed by such matters, the subliminally infused myth developed a life of its own, as you'll recognize by looking closely at Bava's interpretation, or Smolderen and Clérisse's. Though the former lacks stringency in narration despite its visual finesse, the Franco-Belgian duo once more – after their idiosyncratically furnished biography of science-fiction writer Cordwainer Smith – proves its capability of turning unusual source material into excellent comics.

For 2014's Atomic Empire is not only reverting to elements lifted from the writings of Smith, whose actual name was Paul Linebarger, but also includes excerpts from works of other writers Smith was referencing, all the while adapting his curriculum vitae in a partially embellished form. Driven by enormous dexterity, the interposing of Captain Future creator and later Superman writer Edmond Hamilton's The Star Kings and its all-doubting psychiatrist can be considered as a reference to The Jet-Propelled Couch, which tells of an anonymous client in psychiatric treatment who might have been Smith/Linebarger. The Star Kings, furthermore transferring the plot of The Prisoner of Zenda into the genre of science fiction, is just another meta level within a comic borrowing its title from A. E. van Vogt's Empire of the Atom, which in turn is based on I, Claudius by Robert Graves.

Seriatim, Van Vogt was moving in the orbit of L. Ron Hubbard, writer of science fiction of questionable quality and founder of Scientology. Hubbard appears in the comic somewhat camouflaged as an opponent of Smith/Linebarger's. And in all of that well-calculated hustle and bustle of numerous associations legendary Franco-Belgian cartoonist André Franquin rushes past on a bicycle – these are moments where reality and exaggeration are generating a new kind of quality by interlocking with each other. Comparisons to the better works of Alan Moore and Grant Morrison are definitely permitted here.

Seriatim, Van Vogt was moving in the orbit of L. Ron Hubbard, writer of science fiction of questionable quality and founder of Scientology. Hubbard appears in the comic somewhat camouflaged as an opponent of Smith/Linebarger's. And in all of that well-calculated hustle and bustle of numerous associations legendary Franco-Belgian cartoonist André Franquin rushes past on a bicycle – these are moments where reality and exaggeration are generating a new kind of quality by interlocking with each other. Comparisons to the better works of Alan Moore and Grant Morrison are definitely permitted here.

Even so, this meta-level biography is consumable without knowing all the multi-layers interwoven, a thing that can't be said about Morrison's Watchmen pastiche Pax Americana, also from 2014, and its asinine tree-house-just-for-boys attitude.

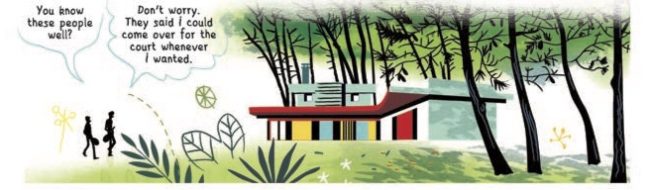

Clérisse's art sticks to the retro style established in the predecessor to Diabolical Summer, but you'll notice a brightening of the colors. They start out with the psychogram of a tormented mind as it was done in muted colors for Atomic Empire, but then reach for a brightly shining summer panorama charged with the ubiquitous great promise of imminent sexual liaisons, though sometimes blurred by violent premonitions of dishonesty and violence in dark violet tones. In terms of page layout, the lack of panel borders is a matter of honor and of paying tribute to the psychedelic flow of the era the story is set in, with best regards from Guy Peellaert's Jodelle and Pravda.

Clérisse's art sticks to the retro style established in the predecessor to Diabolical Summer, but you'll notice a brightening of the colors. They start out with the psychogram of a tormented mind as it was done in muted colors for Atomic Empire, but then reach for a brightly shining summer panorama charged with the ubiquitous great promise of imminent sexual liaisons, though sometimes blurred by violent premonitions of dishonesty and violence in dark violet tones. In terms of page layout, the lack of panel borders is a matter of honor and of paying tribute to the psychedelic flow of the era the story is set in, with best regards from Guy Peellaert's Jodelle and Pravda.

The only thing devoid of color here, in the sense of interpretable relevance, is the cited Procol Harum song "A Whiter Shade of Pale," which not only serves as an audiovisual means to pinpoint the time frame, but also forms a base for a senses-stimulating sequence. The arcane lyrics fed into the novel Barefoot in the Head by Brian W. Aldiss – the Ulysses of 1960s New Wave science fiction – to capture the lysergic acid diethylamide-drenched mood of that era. For Smolderen, who in addition to numerous essays has written a history of comics and teaches at École des Beaux-Arts in Angoulême, Procol Harum's intent to have the gaps emerging from within the song's lyrics filled by the audience's imagination must have been easy prey with a view to prevalent comics theories, as they are a welcome opportunity for his partner in crime Clérisse to make the letters of the alphabet dance with feral fonts.

Appropriately for Diabolik, Smolderen and Clérisse keep it simple structurally: After the anamnesis dissolved in catharsis that was Atomic Empire, Diabolical Summer is a bulbous and curvy coming-of-age fable spiked with pop-culture set pieces visually translated in shades of pop-art color. It tells the story of young fellow Antoine, who has an aloof relationship to his father that is defined by a spatial and temporal distance and appears to be some kind of a shady character with a history going back to the intelligence business.

According to his age, Antoine naturally has to face some Sturm und Drang along the way, which includes the negative influence of friends who appear fascinating and dubious, as well as the awakening of sexual desires transferred into a brilliantly depicted reverie.

According to his age, Antoine naturally has to face some Sturm und Drang along the way, which includes the negative influence of friends who appear fascinating and dubious, as well as the awakening of sexual desires transferred into a brilliantly depicted reverie.

Also included? JFK's assassination and the Cold War; every distraction is welcome. And so a fumetto nero like Diabolik appears to also be the result of a misspent youth at newsstands, much the same as Paul Linebarger's life was brought into a maddening planetary orbit by trashy magazines dedicated to the possible worlds of tomorrow. The repetition of the motif is pointing to the underlying conceptual structure of a trilogy. In addition to the aforementioned afterword by Smolderen, entitled "Born Under the Sign of the Newsstand," at least in its French and German editions, the dramaturgy of colors for the pages leading into and out of Atomic Empire are anticipating the lighter tones of its successor. However, the third and final volume was announced last year as Une année sans Cthulhu, which translates as A Year without Cthulhu.

Smolderen and Clérisse once again demonstrate that it's entirely possible to craft long-form comics thematically related to biographies and works of literature that don't end up being predictable cash-ins – well, if you consider Diabolik being a literary thing at all, that is. And this second collaboration by the two authors also represents an improvement over the first: The life history of Antoine is easier to follow than the abstractions of Paul Linebarger's complicated mind, if only because every generation shares similar experiences while growing up.