Professional Offenders

Reynolds: I moved to Seattle in June of 1993 to intern for The Comics Journal. I lived with Gary for the first three months. It was a real thrill for me, because he was still very engaged with the Journal and so I really immersed myself in it quite quickly. I fit in. I had basically spent all of my teenage years in a comic-book store and had a broad knowledge of comic-book history and the industry. I was a cartoonist myself, but I also went to college, where I was the managing editor for the weekly paper, earned a literature degree and became interested in muckraking journalism. I was completely simpatico with the Journal’s mission, and had a unique skill set that I don’t think fell into their lap too often. So Gary and I hit it off pretty quickly, and I also hit it off with the guys closer to my age, like Jim Blanchard and Thom Powers. I felt at home almost immediately.

Scott Nybakken was the first managing editor that I worked with. He was a good guy and one of the few Journal editors I can think of who really didn’t bring any ego to the job. It was not surprising that he parlayed the gig into a long and successful career at DC Comics.

Tom Spurgeon: I got to The Comics Journal in 1994, replacing Scott Nybakken, who restored some sanity to the magazine after a few years of super-volatile personalities and was organized enough that he had a year and a half of the magazine planned ahead. He even left good files. I stayed for about five years, which, at the time, was kind of the world record for Journal editors.

The same way the marketing department started to get more people that actually knew something about marketing, the big change at the Journal as the ’90s went on was news editors that knew about writing news — or at least they had some journalism training at college or something similar — and were willing to give it a shot in the magazine on a regular basis. Eric Reynolds wrote really patient and fearless news, he was just relentless and did all the grunt work that sometimes was missing from fan reports and now gets skipped over online. Plus someone trusted him enough to send him memos from Paul Levitz’s desk. John Ronan and Greg Stump could write a long story and make it funny and interesting, and since they were both basically comics outsiders, they dropped coverage on a lot of day-in, day-out publishing news that was kind of the legacy of the fanzine era.

Groth: The magazine’s journalism took off when Tom Heintjes started writing news in the ’80s — Tom was the first outside news writer who was truly committed to investigative journalism. The news column was a hit-or-miss prospect from then on depending on who was handling the news. Some were better than others. Greg Baisden was very good, as I said. Eric actually had some real journalism experience in college and, just as importantly, had the right truth-telling attitude.

Reynolds: You had to either find reward in the work itself or quickly burn out, because it’s not like anyone was complimenting you on your efforts. The only feedback was negative feedback, really, because of the magazine’s contentious relationship with the industry. I very much thrived on the conflict. Spurgeon did, too. You can see it in the issues we worked on together. I think we provided some much-needed stability for a few years, after a revolving door of misfit editors.

Spurgeon: None of us could line-edit or proofread worth a damn, and we always ended up after every issue with a stomach ache because of things we could have done better, but I think Eric and Greg [Stump] and John [Ronan] and I were able to give the Journal a sensibility more in line with modern comics. We avoided prolonging a lot of the feuds for the sake of prolonging them and dumped some of the Seattle scene-heavy stuff that had been running, like a Hit List recommendation for anyone in Seattle who pumped out a comic written by that cartoonist’s roommate. We walked away from covering a lot of artists with only a tangential relationship to comics and more back into comics proper. We nudged the magazine’s humorous moments into the direction of broader, mainstream snark and away from humor based on characters and concepts, like Sub-Mariner on Jeopardy! or whatever. We had David Lasky and Greg Stump and even Mark Martin doing editorial cartoons.

The hardest thing to do at the Journal was working with Gary, and the second hardest was dealing with Kim when he would drop in with some devastating note. They were the most rewarding things, though, too.

David Lasky: Tom Spurgeon was a really obsessive guy, a workaholic.

Thompson: Tom was one of the good Journal editors. Smart, knowledgeable, a hard worker, not a sociopath. Really, there was a period there in the ’90s where “not a sociopath” was one of the major criteria we set ourselves in trying to recruit Journal editors. Often we’d fail to meet it. But Tom gave us a half-decade of blessed relief.

Spurgeon: The mid-’90s was a fascinating time for comics because many of the first great alternative comics talents had found a second, even more considerable wind — books like Poison River and Our Cancer Year and Palestine — and then there was this new wave of emerging talent like Al Columbia and Renée French and Tom Hart and Paul Pope that were less tethered into more traditional styles and forms and were scattered among a variety of publishers.

Throw in the 1990s wave of minicomics and the Understanding Comics influence, this kind of casual formalism that Scott McCloud made popular, and 24-Hour comics, and Drawn and Quarterly and Black Eye putting out smartly designed books, and Chris Ware, and even things like Mark Waid and Kurt Busiek coming up with an affectionate correction to grim and gritty mainstream comics, and it was a heady time. Throw in a series of explosive financial setbacks and corruption and it was a dream industry to cover.

Reynolds: I started interning the summer of 1993, and was handed the news editor reigns at the beginning of 1994. As I began work on my first issue at the helm, Jack Kirby died and I had to write his obituary. I was 22 and calling people like Will Eisner and Gil Kane to ask them for quotes about their dead friend. At the same time, the direct market was starting to go sideways after the collapse of the latest speculator boom, and I wrote a long analysis of the market that drew a conclusion that the then-still-nascent Image Comics’ poor business practices and late shipping were largely to blame. I think I wrote over 30 pages of news in that first issue I edited. Trial by fire.

Jules Feiffer: I appreciate and enjoy reading in The Comics Journal the level of criticism and the area covered, the territory covered, by the various writers for the publication. And I would say more times than not, I was not even acquainted with some of the people they were writing about. And sometimes I didn’t find it interesting at all, I didn’t like what they did, but I was amazed at the breadth of the coverage and I am to this day.

Reynolds: In 1994–95, I had pretty quickly developed two primary interests in my focus as news editor, in addition to whatever was happening from month to month. I was covering the tumultuous fluctuations in the direct market stemming from a speculator boom and bust cycle in the early 1990s as well as the formation of Image Comics by a bunch of Marvel Comics defectors in 1992. We covered the industry with a critical eye, like a self-appointed ombudsman. And then I was also covering First Amendment issues, notably the goings on of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, which at least in theory was simpatico with the Journal’s mission. I initially engaged the CBLDF much more as a booster, trying to amplify the signal for the free speech cases they were defending. But my relationship with them quickly became more complicated, as most things at the Journal usually did.

The CBLDF had one especially high-profile case at the time. Florida cartoonist Mike Diana was being prosecuted for publishing, distributing and advertising obscene material in the form of his underground zine, Boiled Angel. In early 1994, he was found guilty. The sentence was a gross violation of Diana’s First Amendment rights, forbidding him from even creating any new “obscene” material even for his own personal use.

I do consider our coverage of the Diana case to be amongst the best reporting that TCJ ever did, although it got somewhat overshadowed by the distribution wars that quickly overwhelmed the direct market.

Spurgeon: Gary and I yelled at each other a lot, mostly because I would fail to get stuff done on a regular basis and then lie about it. One day I was walking into the office and Gary’s window was facing the parking lot and Gary saw me and was mad at me so he yelled “Hey! Fuck you!” And I screamed back, “Fuck you! Asshole!” and gave him the finger as I went down into the basement. Sitting at my desk it hit me how weird it was to yell at your boss like that.

Once Gary wondered why I hadn’t gotten an article in and I told him that the writer was never at home. So he grabs his call sheet and dials the number on the speaker phone and when the poor writer picked up, saying “Hello?” Gary slammed the phone down, hanging up on him. “He’s sure home now!”

Groth: When Spurge took over the managing editor duties on the Journal, I was pretty involved in the day to day running of the magazine. That must’ve been around ’93. By late ’94, my domestic situation had become like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf on a loop and as a result of this distraction my professional focus slipped … for several years. It was all I could do to focus on our books and maintain the day-to-day operations of the company, and our creators were my first priority, so my involvement on the Journal kept slipping. I basically put all my forensic energy into my relationship and had little left over for the Journal. As I was able to devote less time to the Journal, Spurge took up the slack. He took on more work as I became more sidelined and he did a hell of a job keeping things running.

Spurgeon: The biggest character of all the people in the Journal office in the late ’90s was probably John Ronan. John was really, really loud. When he came in in the morning you could hear him through the walls and floor walking through the office and saying good morning to various people, with this thick Boston accent, like a version of The Family Circus where you heard instead of saw Jeffy’s footprints.

When I decided to make the leap from the Journal to the Fantagraphics side of things, John seemed like a natural to replace me and I convinced Gary to hire him, largely because I wanted my buddy to move to Seattle. I thought it would be a match made in heaven, but it wasn’t.

Groth: I liked John a lot and I liked his blustery Jimmy Breslin personality, but I thought his writing was sloppy, so we’d butt heads over that. He was a bulldoggish reporter, but there would be odd holes in his stories, which resulted in a tumultuous relationship between us. He was A.J. Liebling compared to the idiots that followed him, though.

Chris Jacobs: Also, he smoked Newports.

Peter Bagge: I did mention to Eric, when he started [in marketing], that he should try to distance himself from The Comics Journal. Though I’d never give that advice to anyone now. But back then, the Journal was much more controversial and combative than it is now. Gary had a lot of “enemies” back then, and these adversarial relationships sometimes interfered with doing simple business for Fantagraphics in general. All I was saying is just change the subject if any TCJ crap would come up, and try to sell Fantagraphics The Publisher as a separate entity from the Journal as much as possible.

Reynolds: Pete gave me a hand-written cheat sheet called “The Fantagraphics Game Plan by Coach Pete Bagge.” One of the rules was, “When someone brings up Gary Groth or The Comics Journal, CHANGE THE SUBJECT!” It was good advice.

Bagge: That conflict no longer seems to be as much of an issue, though. Or if it is I’m not too aware of it. A shame in a way, since I found the old, muckraking Journal a more entertaining read, in spite of the problems it caused! Still, it’s better for business that they’ve toned down that aspect of the Journal.

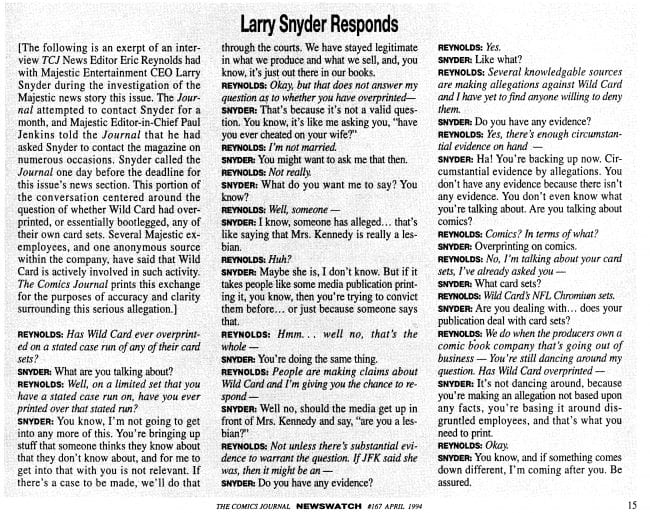

Reynolds: For all the enmity the Journal could stir up, I was only physically threatened once, over a story about a 1990s publisher called Majestic, which was allegedly engaging in fraud by overprinting “limited edition” product and selling it out the back of their factory in the middle of the night. It was a really bizarre story of corruption that included anecdotes about key figures in the company speaking in tongues during meetings. When I confronted the CEO of the company for comment, he threatened to “come after me” if I reported any of this. He sounded dead serious, and I remember being taken aback by it, but also kind of exhilarated, because I knew I had these guys dead to rights. We ran the complete transcript of our conversation as a final sidebar to the end of a very long feature story.

Joe Casey: I think the magazine has always been pretty spot-on when it decides to cover the so-called “mainstream” areas of the industry. My personal feeling was that, when the Journal wasn’t talking about superheroes, it was because nothing particularly interesting or worthwhile was being produced in that realm.

Rebecca Bowen, personal journals, 1994:

Jack Kirby died and I was calling people to get their permission to reprint past nice things they’d said re: Kirby. Couldn’t get some of 'em — so Gary gave me people to call to ask for other people’s numbers. I called one guy and asked for a couple of numbers. He didn’t give them to me, was offended that’s the only reason I’d called and told me to tell Gary, "Go stick your head in an electric fan!" Realized later I’d forgotten to ask him to write a couple of paragraphs also — my fault! Gary told me to tell him: "Every time I feel like sticking my head in a fan, I call you instead!”

Groth: Rebecca worked there as an intern. We were working on a Jack Kirby tribute after Kirby passed away, and one of the jobs I gave her was to call up professionals and ask them if they could talk about Jack Kirby or write something about him. I gave her a list and one of the people on the list was the writer Bob Kanigher. Kanigher was cranky and not a little bitter and in semi-retirement at this point. Rebecca taped all her calls, so I listened to her conversation with Kanigher. At some point very early on in her conversation with Kanigher, it became apparent to Kanigher that Rebecca knew nothing about mainstream comics. Her job was simply to ask the professional if he wanted to contribute to the Kirby tribute, so knowing the history of mainstream comic-book characters was not required for her to do her job. Kanigher bristled when Rebecca admitted that she wasn’t familiar with Kanigher’s contribution to comics. “Have you read the Metal Men?” he practically bellowed into the phone. She admitted she hadn’t. He asked her if she went to college. She did. “What do they teach you there?” he demanded to know, appalled that she hadn’t taken a class on him or the Metal Men. He then went on to lecture her about his creation of the Metal Men. She sat there politely listening. Then, he refused to say anything about Kirby.

Spurgeon: Another big change that the internet brought on was that you could recruit people to write for the magazine after reading what they wrote on different forums or on mailings lists. That’s how we found Bart Beaty, and he was a godsend in terms of introducing the new European comics to TCJ readers.

The big advantage I had over people that followed me was that in terms of cover subjects the late ’90s went through this last rush of interesting alternative comics people and hit this second wave of mainstream greats and the magazine had been out long enough to re-interview some people, so Gary was happier to contribute. His Gil Kane interview is a heartbreaker. Gary has to be protected editorially a bit as an opinion writer to make sure he doesn’t race ahead of all the facts, and he seems only sporadically interested in the news, particularly process-type pieces, but his interviews are impeccable.

Groth: For a good interview I’ve got to be interested in the artist. I’ve got to want to be able to ask the artist questions that he hasn’t been asked before that I don’t know the answers to. There are fewer interview subjects these days that I’m passionate about.

Past that, the important thing is just to be prepared, to read everything you can by the artist and about the person. The other thing, for me, is that it’s closer to a conversation than an interview. I find that to be the most rewarding kind of colloquy, rather than just sitting there and asking prepared questions; you make the interview as organic as possible. I don’t know if that’s good or bad, but that’s the only way I can do it. Sometimes it works, and sometimes it works less well.

Windsor-Smith: One summer evening in 1971, young Gary Groth traveled into New York City, under the supervision of his father, to do an extensive interview with me at my glamorously expensive apartment with a stunning view of Manhattan on 72nd Street next to the Dakota. After completing the tape-recorded interview, during which the older Mr. Groth and I shared some genial chat and several mugs of good English tea, Gary assured me that he’d got a wonderful interview and would quickly transcribe it for his fledgling publication called Fantastic Journal, Comics Fanzine or some such title.

A few months later I received a printed and stapled copy through the mail. Imagine my upset at discovering that Gary had bumped my interview to a secondary slot in favor of a Sal Buscema cover depicting an awkwardly drawn Dr. Strange — that totally stupid version where he had no fucking face. Me, the unwitting golden cum-spot of the early 1970s, reduced to an afterthought by my youthful new pal Gary.

In 1996, I agreed to a second interview with Gary Groth, a quarter-century after the first, this time to be published in The Comics Journal. The interview went OK, I guess, and this time he didn’t toss my cover for some flavor-of-the week pissant penciler. But — and there is always a but with Gary — the letters column of the following issue published only one reader response to the GG/BWS interview. “Bullshit,” said the letter writer. And presumably the editor of The Comics Journal, older but only wiser by the default of time, must have agreed. I always meant to write Gary a nasty note about that, but, y’know, small things fall through the cracks.

Groth: A reader wrote a long letter excoriating Barry and my interview with him. It was so hostile it seemed personal. This prompted me to write a vociferous response defending Barry that was at least as long as the original letter.

Feiffer: What I’ve always found about Gary’s criticism is that it can be very tough, but he’s never interested in hearing the sound of his own voice. It’s not about ego, it’s not about how smart he is. He’s really interested in the subject matter. He’s a true intellectual in regard to this form. And that’s what attracts me to him in general and his approach. It’s something he clearly is serious about, but also there’s none of the aspect — that one finds in so much of any art form — of the showoff and the smart-ass.

(continued in Part Two)