The following is an excerpt from We Told You So: Comics as Art, the long-awaited oral history of Fantagraphics Books put together by Tom Spurgeon with Michael Dean. The uncanonization of a direct sales manager; criticizing Will Eisner; the mole in the Journal; Fiore vs. Pekar; Capital City vs. Diamond.

(continued from Part One.)

Lighting the Feuds

Powers: There have been so many feuds it makes you wonder if there’s something peculiar to Fantagraphics that causes this pattern. I’m not sure I have an answer for that.

Groth: The Comics Journal was in a particularly contentious period in its contentious history by the beginning of the 1990s. We’d just gotten off of our campaign to shame Marvel into returning Jack Kirby’s art; we’d just won three libel suits in a row; independent publishers were gaining traction; the self-publishing movement was afoot; Marvel and DC were still dominant, of course. I saw the Journal’s mission as continuing to be a provocateur, to shake things up, to continue to challenge the status quo.

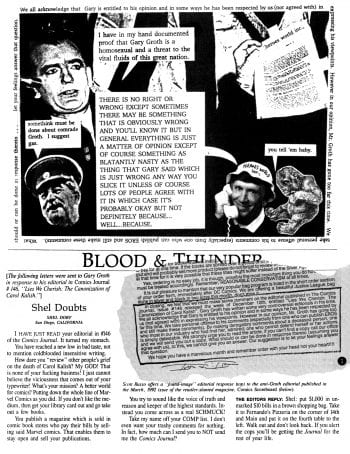

I wrote a couple pieces that caused a surprising and to my mind inordinate amount of controversy and condemnation. I wrote an editorial about the public response to Carol Kalish’s death, something I’m still pleased with. I was chewing off my lips for something like two months, because I didn’t want to write what I eventually wrote. Every week, I would get The Buyer’s Guide, and every week I would read these preposterous hagiographic letters and essays about Kalish. They became more and more attenuated reality. There were eventually letters from people who had never met her or even knew who she was, but who were praising her based on previous letters from people praising her, which were based on something Peter David said a month earlier. So, eventually, I decided that the context required me to try to redress the balance. And my objection was less toward Kalish herself than toward these mindless, over-the-top panegyrics about her, unrelated to her real contribution to comics or even who she was. I think that she got more ink after she died than Kirby, Hogarth, Caniff, Kurtzman, all these great artists, did.

I think the reason for that was probably because she was a professional networker. People get praised more because of their networking skills than because they’re great artists, and that offended me; it seemed like an utterly lopsided set of values at work. Fewer people knew and liked Burne Hogarth, so he got virtually no coverage, but because Carol Kalish was the friend of all retailers, she was smothered in praise. So anyway, I don’t know, it seems ridiculous in retrospect, because my piece was like what, 2,000 words, or something like that? It was a short, succinct piece. And you know, the ironic thing is it might have even created more of a shitstorm than my piece on Eisner.

Gary Groth, “Lies We Cherish: The Canonization of Carol Kalish,” The Comics Journal #146 November 1991:

Of course, her job was to sell as much semi-literate junk to a gullible public as humanly possible. Her gift — or genius — was exploiting markets, manipulating public taste, pandering to the lowest common denominator. She was, in an odd sort of way, forthright about the crassness of her employer’s marketing methods. Once I witnessed a retailer timidly question Marvel’s strategy of filling their comics with sex and violence: Kalish’s reply, which was almost refreshingly free of the specious nod to morality to which less assured marketing tacticians would resort, was that little boys liked sex and violence and Marvel was in the business of selling comics to little boys. Hence and therefore.

Thompson: I understand why people were offended by Gary’s piece, but a lot of the criticism was off base. First, that it was written “too soon” — it was months after Kalish’s death — and second that it was an attack on Kalish herself. I suspect that to this day a lot of people who bear a grudge toward Gary never read the original editorial, just other people’s interpretations of it … or if they did finally read it, their perception had already been so colored by the outrage.

Groth: I reread my Eisner piece not too long ago, and it wasn’t bad. I stand behind it, but my God, it created another shitstorm. Even Jules Feiffer raked me over the coals for it in my interview with him. No one was allowed to say anything critical about Eisner then. I think that’s changed since, but in 1989, he was critically inviolate.

Gary Groth, “Will Eisner: A Second Opinion,” The Comics Journal #119, January 1988:

There are, it seems to me, two Will Eisners: The populist who defends mass-market junk and the elitist who champions comics as a form of literature; a shrewd businessman who prides himself on deal making and market savvy and an artist whose aspirations rise above the marketplace; an artist who uses his (and others’) gifts to package utilitarian products-to-order and an artist who strives to duplicate the human condition.

Feiffer: I thought Gary’s essay on Will Eisner was quite harsh. What was refreshing was that he was one of the few people not enamored of Eisner and didn’t genuflect, but at the same time I thought he went overboard in his judgments. There were all sorts of criticisms of Eisner’s work that I thought were legitimate; I didn’t feel like Gary in some instances was on the money here.

Groth: I wasn’t rabid about Eisner, particularly, but I couldn’t understand why no one else noticed that his graphic novels were really lousy, and lousy in an obvious and pronounced way. It pretty much shot my relationship with Eisner, who never forgave me — another example of naiveté on my part, though I probably never even considered that aspect of it when I sat down to write it.

Gary Groth, “Will Eisner: A Second Opinion,” The Comics Journal #119, January 1988:

These observations were prompted by my reading of The Building, and two blurbs from Don Thompson and Max Allan Collins that Kitchen Sink is using to advertise the book. Uncle Don thinks The Building is “inspirational” and “outstanding,” while Collins thinks it’s a “brilliant, graceful graphic novel” that brought tears to his “cynical eyes.” In fact, The Building may be Eisner’s worst book, a menagerie of clichés and an embarrassingly strident use of a hoary, heavy-handed literary device that could be productively employed in schools throughout the country as an example of how not to write a story, but which wouldn’t fail to impress our average comics reviewer as an example of High Art.

Groth: So again, I wanted to introduce a contrarian point of view to the public discourse. There’s nothing that comics fans hate more than something that upsets their little critical apple cart. I got hell for it; I think Don Thompson said I wrote it out of jealousy. But looking back on it, I would fine-tune it a little bit, but I think I was pretty accurate. God knows, considering what he’s done since then, I think it was probably pretty lenient.

Dave Sim and I went ’round and ’round. My disagreements with Dave — and this is long before he wrote that deranged anti-woman screed — were many. One, I remember, was his adoration of self-publishing irrespective of the quality of the self-publisher. I guess I thought that there was something about Dave’s worldview that was skewed and defective and fundamentally amoral … although I didn’t know how skewed at that time.

I haven’t looked at this in ages, but I think we had a back-and-forth where I wrote a couple of pieces about him, and he wrote a big piece about me in Cerebus, and naturally I wrote a response and so forth. It was one thing after another. I remember Dave also attacked Bud Plant over some utterly specious nonsense, and I mean Bud is probably one of the few fucking saints in the comics industry. So they had this big brouhaha, and not too long after that, Sim was palling around with Steve Geppi and lifting brewskis and watching football games with him. Earlier he had taken this exhibitionistically moral stance about what an unethical person Geppi was, and then shortly thereafter he’s buddying up to him. So I think he was displaying signs of neo-Ayn-Randian economic models back then that were sort of seeping out of his writing, which I thought were morally dicey. I think I went after that too.

At the time, these were like life-and-death issues and I wrote with that kind of urgency. Looking back, perhaps that was naive, but I wouldn’t mitigate that passion, in retrospect, for anything.

One day someone from Capital City called. I forget the guy’s name, but he was an executive at Capital, and I guess I wrote an editorial where I specifically referred to him as a schlockmeister. So, one day someone who answered the phone in my office buzzed me and tells me, “There’s a call for you.”

I said, “Who is it?”

And he said, “Well, he just said, ‘It’s the schlockmeister.’” So I took the call and this guy just yelled at me for five minutes. He was right in the sense that the reductio ad absurdum of my argument that he was responding to was that he probably shouldn’t have a job, and that 90 percent of the comics that Capital was distributing shouldn’t exist. But he was really personally, deeply offended by this.

That kind of conviction about art and what culture ought to be, and what excellence is and what we should be devoting ourselves to was beginning to be sidelined by an overwhelming commercial ethos.

Image probably had a lot to do with that — empowering mediocrity. That was a revolting spectacle, honorable men running to Image because Image suddenly had lots of money and power and clout. And because it was run by creators and creators were intrinsically the good guys.

I haven’t read the Creator Bill of Rights in a couple decades, but as I recall, I was somewhat skeptical of whether this was going to enhance the art form — and that’s what I wanted to do, that was my primary interest, that’s what I thought it was all about. I found a lot of these reformist or semi-reformist agendas, like Scott McCloud’s and Dave Sim’s, were more about giving shitty artists a bigger cut of the pie than anything having to do with art. In a lot of instances, I was not railing against the corporate mentality as embodied by corporations but the corporate mentality as it had been internalized by the more vocal creators.

I was banging my head against that wall, and the wall was winning. Apathy had taken the place of a more activist kind of agenda on the part of creators.

I couldn’t in good conscience champion the guy who pencils and inks Justice League of America. I mean, he probably makes a very good living. He doesn’t own the work. He knows that going in; it’s all work for hire, I think that you can make an argument that work for hire is intrinsically bad. It is just part of this whole commercial culture that encourages people to divorce themselves from their own work in any meaningful way. But you know, nobody’s going to listen to that argument.

Powers: There was a big break between Gary and Denis Kitchen.

Thompson: Kitchen Sink was falling apart, and not only was it falling apart, there was some weird stuff going on in its relationship with Tundra, with which it was merging. It was the big story at the time, and Gary was adamant that it should be pursued in the Journal, as well it should. Kitchen saw this as an attempt to sabotage him, and his paranoia was exacerbated when the Journal editor of the time, Carole Sobocinski, decided to become a mole for him inside the Journal.

Groth: I had what I would characterize as a collegial relationship with Denis Kitchen through the ’80s. We weren’t close friends, but we both suffered the same tribulations as marginal, alternative comics publishers, and we’d often gossip and commiserate at cons and at parties, and over the phone. I certainly considered him a collegial friend or a friendly colleague. He was always supportive of the Journal’s journalistic mission — he had been a journalist himself briefly — and he often complimented the magazine on its hard-hitting news coverage.

In the early ’90s, Kitchen Sink Press was going through he same miserable financial contractions we were. I think he was circling the drain just as we were. We solved our problem by starting Eros Comix. Kitchen tried to solve his by merging with Tundra, the alternative publishing company Kevin Eastman founded in 1990 and sunk his millions in.

Kitchen issued a press release in 1993 announcing Kitchen Sink’s purchase of Tundra. This was suspicious on the face of it; companies on the brink of bankruptcy don’t buy companies who are three or four times their size. My journalistic bullshit detector went off. This made as much sense as Fantagraphics buying Random House. We proceeded to do our job, which was to dig up the truth, and this put us in direct contention with Kitchen who did his best to prevaricate and hide the truth. As it turned out, according to what Eastman subsequently told me in his Journal interview, he, Eastman, has initially owned 51 percent of Kitchen for a while, and even financed the merger or acquisition to the tune of 2 million dollars — the opposite of how the transaction was portrayed by Kitchen. It became more personal when, during the course of our reportage I thought we were being stonewalled, I had a conversation with Kitchen and he told me he would answer our questions honestly or tell us when he couldn’t answer them, but insisted on the subterfuge that Kitchen had purchased Tundra. All this time, unbeknownst to me, our news editor and news writer were in cahoots with Kitchen to suppress the story.

Powers: I visited Denis Kitchen back when Kitchen Sink was in Wisconsin, back when I was briefly the executive director of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. I visited Denis, stayed at his place, and on the way over people were saying, “Happy birthday, Denis.” In this low-key way he hadn’t bothered to disclose, it was his birthday.

Later that trip he said, “I started a publishing company to control my own work, but now this company controls me.” And I think that’s true for so many entrepreneurs and small businesspeople.

Marc Arsenault, designer and former Tundra employee: [Gary] called me up one afternoon, and what he had to say was a bit of a shock. He apologized to me. Apparently, a couple of members of The Comics Journal staff decided that what I and other former employees and associates of Kevin Eastman’s Tundra Publishing had to say about our time there was so horrendous, that — journalistic ethics be damned — it would be a good idea to let Denis Kitchen know what was up, off-the-record comments recorded without my permission or knowledge [in the course of their alleged news writing], and all.

Groth: Over the course of several months when this story was hot, I was increasingly frustrated because the Journal’s news writer simply wasn’t getting the story. He would submit drafts that were woefully feckless and evasive, I would return them for a rewrite with specific notes as to whom to talk to and what questions to ask, I would get another half-assed draft and this would go on and on. The managing editor kept telling me she was on the news writer and couldn’t understand why he was doing such a poor job either. What I didn’t know is that they were both in constant touch with Kitchen, had agreed to sabotage the news story and were feeding him information about how successful they were in undercutting the story.

I only learned about this when an intern working under them whom they had taken into their confidence came to me and confessed the whole cover-up. When I called Sobocinski at home and told her I wanted to meet with her, she never came back to work, and the next thing I knew Kitchen had hired her as his assistant.

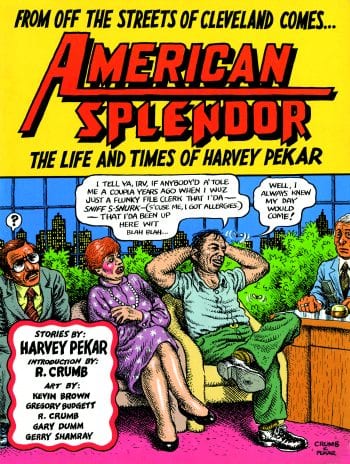

Ilse Thompson: The first collection of The Complete Crumb Comics that I edited started the first years of American Splendor. Because Crumb and Harvey Pekar both own the copyright on their collaborations, we had to get permission from Pekar to publish the work. He was against it. He wouldn’t. Crumb eventually persuaded him, and I got a memo from Gary saying that he had relented. When the book came out, I was arranging for complimentary copies to be sent to contributors, and calling people to confirm their addresses. I called Pekar, who popped a cork when I told him that American Splendor had been reprinted. He had forgotten that he’d OK’d it. “Gimme Groth! I’m going to sue him!” He demanded to speak with anyone in a position above me. I was afraid to tell him that I had edited it, and told him that everyone else was at lunch, because I didn’t want anyone to know I’d pissed him off.

The next morning, Kim told me that Pekar had called to apologize to me, and that I should expect a call from him. When he called, we spent an hour on the phone. He gave me a lesson in Russian literature.

Groth: At first, Pekar refused to give permission to reprint the strips Crumb drew from his scripts. I had to call Crumb and ask him to call Pekar and intercede, which he did. My impression was that Pekar refused permission either because of some feud he was having either with Bob Fiore at the time or an argument I had with his wife Joyce Brabner, but which I remember thinking was a petty reason to deny his collaborator the right to include those strips in his complete works.

R. Fiore: The Harvey Pekar business was one of the more idiotic episodes I’ve ever been involved in. One thing to remember was that it came during that whole period when the move was being made and my return from Seattle, and if you read anything I was writing at the time you’ll see that I was just in a foul mood. You could see it in that ridiculous feud we were carrying on with the Comics Buyer’s Guide, overheated rhetoric mostly provided by me, as if we were in a death struggle with Don Thompson for the soul of the comics, (a) as though they had one and (b) as though it would have been worth having. I am put in mind of Jorge Luis Borges’ description of the Falkland Islands War: Two bald men fighting over a comb.

Thompson: The Fiore/Pekar feud highlights one of the problems, which is that people would inevitably take the writing of one person in the Journal as a company-wide broadside, and generalize their dislike of that person into a loathing for the Journal and Fantagraphics as a whole. So a lot of people hate Gary for nasty reviews of their work that Gary may not agree with, or even have read.

Powers: For years I made pitiful attempts to get Bob to write in other venues. I published my own paper in Detroit in 1993, and I got Bob to write a column for me. Unfortunately, I only published three issues. I once gave copies of the papers to Christopher Hitchens and Hitchens asked me later, “Who’s Bob Fiore? He’s a great writer.”

Fiore: The biggest problem with the position I took with Pekar [re: the reductive use of animals in Art Spiegelman’s Maus] was that Pekar had a point, in that characterizing a people as pigs does have a certain connotation. The real answer to this is that, while it is a problem, Spiegelman defuses it by portraying Poles in a multidimensional way. The thing is, right at the time I was writing that column, I had heard this thing on NPR about Polish collaboration during the Holocaust, and I made this dumbass comment to the effect that, in making them pigs, Spiegelman was being too kind. Needless to say, this was not the way in which Spiegelman wanted to see his work defended. Anyway, having climbed out on this limb, I proceeded in the finest Field Marshal Haig fashion to defend it. What the episode proves is that the things that are most likely to make you look foolish in an argument are ego involvement and emotional involvement.

What impressed me about Pekar is that he actually went out and read The Lost Steps, much more of a commitment than I would have made in the same circumstances. (It actually is a book about a modern man who discovers a primitive society that he finds superior to the modern world and all its conveniences, but Pekar did some selective quotation that made it look otherwise. The dirty cheat.) What burns me up is that I found a quote from Orwell that said that Animal Farm was an allegory of the Russian Revolution, but it was too late. This was the sort of absurd point we went round and round on; Pekar would take a position that was objectively wrong but because of my ego involvement I kept trying to make him admit it, and that’s something he wouldn’t do. And you really have to wonder if someone who can’t see the difference between Agatha Christie and Raymond Chandler has any genuine understanding of literature at all. The perverse thing is while artists always complain about being judged by people who couldn’t create art, when artists themselves try to judge a work of art they are immediately subjected to invidious comparisons or accusations of professional jealousy.

Groth: I remember Pekar telling me that he would never, ever allow Fiore to have the last word in that argument and that he would argue for the rest of his life if necessary and that if I ever stopped the argument and gave Fiore the last word, Pekar would continue it in the pages of the Comics Buyer’s Guide. It rampaged over many issues of the Journal and Pekar did indeed get the last word. Until now.

(continued on next page)

The Harvey Pekar anecdotes seem off. First of all, Crumb and the other artists Pekar worked with don’t have any formal copyright interest in the American Splendor material. The registrations are solely in Pekar’s name. Beyond that, given the timeframe, I’d be surprised if Pekar was in a position to give permission to use the stories in The Complete Crumb Comics. Four Walls Eight Windows held the book-publishing license for the material in the 1990s, and the decision was most likely theirs. Their Bob ‘n’ Harv Comics collection came out at about the same time as the first Complete Crumb volume with Pekar stories. They would understandably be reluctant about allowing a competing book into the market. In short, I suspect the problem was a business issue, rather than some personal nonsense on Pekar’s end. Joyce Brabner would probably know for sure.

As for the rest of the excerpts from this book, I must say it paints quite a portrait of Gary Groth’s conduct as an employer, his attitude towards employees, and the workplace environment he fostered. The Frank Young sections were particularly telling.

These excerpts are fascinating to read — they don’t seem to enlighten me much on comics as an art, but they are juicy as hell. I cringe to read this stuff and realize how badly business in the comics industry was conducted back in those times. I hope some can learn from this history — but the “sucker club” mentality has persisted throughout American comics, going back to the early days of newspaper strips. One tiny thing I noticed: the Steve Geppi/Alfred E. Neuman mashup identified as a doodle by Eric Reynolds to my eye appears to have the handwriting of art spiegelman in the lower “What? Me worry” part. Either that, or Reynolds’ handwriting is a dead ringer for spiegelman’s, which is certainly possible. The drawing itself looks a lot like spiegelman’s style, as well. The lettering in the two upper balloons is by another hand.

The Comics Journal was started by the same people who started Fantagraphics?

Martin, you sound ridiculous. Crumb, nor any artist, needs to hold the copyright on something to WANT to include it in their books. Things are done informally, work made for the passion of it, its completely normal to try to get something in your collection even if you don’t technically own it. Obviously Crumb felt the work he did with Pekar was significant enough to want to include it in his Complete Crumb collection series. Does that that even need to be clarified? And the idea that because some short strips appear in one book, they can’t appear in a different book of mostly different work is ridiculous especially in Crumb’s case where it seems he rarely, if ever, signed exclusive agreements-at any time, you can buy multiple crumb books with overlapping material. at this moment, the same strips appear in the Complete Weirdo from Last Gasp, The Complete Crumb from Fanta and in Sex Obsessions published by Taschen. Get a grip, dude.

Reading the Fanta oral history, the thing that is most striking about Groth is that he was rallying day and night as if his life depended on it, for something that didn’t even exist-there’s about five years between the start of the journal and his discovery of Love and Rockets. That’s some serious conviction that comics can be literature without actually having an example of what you mean. The other striking thing is, is that kim jumped on already moving train that Groth had built and was already steering with sheer force of will. I love Kim and think of him as Groth’s partner all the way(especially after he lovingly passive-aggressively squeezed Catron out), but Groth was a man on a mission.

sikrillexfan, please reach out to robert martin, and do a podcast together. I think there might be gold there. please post a link here when it’s done.

Honesty Sammy “Harkham”, I’m surprised you had enough balls to think misspelling my name was a good idea. Let me explain what’s happening here to you

This is a oral history book of self-promoting statements describing a critical journal that self-promoted the books that it published, and still does including the self-promotional oral history book I just mentioned.

And you’re mad there is one negative comment and my own slightly satirical anonymous comment?

What would be the motivation of adding any positive encouragement to these people on top of what they’ve already provided themselves? They’ve constantly been telling us so: they won the comic culture wars. Their mailboxes are choked with unwanted submissions they throw into a brand-new green dumpster.

Sure,you can go the “hypocrite” route that robert martin went but that’s beside the point. I’m not interested in that point.

My point is that it’s obvious that fantagraphics has chosen to reinforce it’s image rather than waste their resources on new creators. That’s fine but new creators aren’t going to waste their resources taking this book at face value.

Sure, their image is appealing. I’m into it of course, we’ve all stared at it for years. But soon their won’t be much of a difference between the insider dirt in this book and “The Secret History” by Procopius.

So you see Sammy, you made a mistake. i don’t even listen to skrillex. I’m a 23 years old creator.

so yeah dumbass, maybe there is gold here. I worship myself, just like fantagraphics does. In that way I’m imitating them on a truer path than anyone in Kramers could ever dream of following

I’m with Robert: **based on the excerpts here**, Groth sounds like he fostered an abusive, bullying work environment at the Journal and Fantagraphics. Prima facie, it looks like, if he was working in a business he didn’t own himself, he’d be fired and/or sued, or he ought to be. While we’re at it, it looks like that, secunda and tertia facie, too

Hold the phone–fantagraphics has a NEW green dumpster?

Skrillexfan, huh? good grief I misspelled your internet handle. That’s all, buddy. i liked your post, honest.

Anyhow, another great line in this insanely awesome book comes from jim woodring describing an artist’s work as looking “like Elfquest as rendered by a third-rate Hare Krishna painter.”

Harkham’s response to Martin was epic and long-overdue. Like any human work, a comments thread should know when to quit, and now we’re heading into Before Watchmen/Perpetual Star Wars territory.

I don’t know where I said or implied that Crumb was opposed to including the American Splendor material in The Complete Crumb Comics. I’m sure he’s always been in favor of it.

All I said about Crumb was that he doesn’t appear to have an ownership stake in the material. That means he doesn’t have any rights. He cannot authorize the material’s use.

I also never said that because material is featured in one book it cannot be featured in another. Of course it can. However, when one publisher holds the publishing rights, other publishers are generally required to get that publisher’s permission before including the material in their projects.

That’s why I doubt that Last Gasp, Fantagraphics, and Taschen are all publishing Crumb work from Weirdo on a non-exclusive basis. I would expect that one of them has signed a license with Crumb for exclusive control of the publishing rights. The other two would be including portions of that material in their projects with the first publisher’s permission. I don’t know for sure in this instance, but that’s usually how these situations work.

I would not call The Complete Crumb Comics, Volume 12, and Bob ‘n’ Harv’s Comics “different book[s] of mostly different work.” Over a third of the page count in that Complete Crumb volume—50+ pages–is taken up with Pekar material. That’s a lot of overlap.

Oh course I have nothing personal personal against you, Sammy. I just wanted to make clear to the community that my negativity has been carefully thought through and is multifaceted. Your post read as if it was attempting to lump all the fantagraphics haters together, and I am here to bear witness that we are a diverse group each with our own life story and unique perspective. New strands of this hate are being developed everyday, each more nuanced and exquisite than the last.

Perhaps I should have merely recounted my observation of Fantagraphics at SPX2016. As niche celebrities they walked among us but the niche architecture favored them. What is an impressionable youth like myself to make of this? For a new generation, the conceit that fantagraphics are the underdog is something that must be taught as an historical truth, not something that we can ever learn through experiences.

Dammit, it’s true: Art Spiegelman drew that caricature of Steve Geppi. I was just fronting for him because the political fallout to Spiegelman’s career would have been too devastating were the truth to come out.

What’s amazing is that Groth and someone like Joe Quesada are two sides of the same coin, whatever fundamental differences they have on the presentation, and value, of art. Both are whiny faux-tough guys who have a chip on their shoulder about comic books being taken seriously as some deep art by the unenlightened and elusive “mainstream”. If only they KNEW what deep shit the Europeans think comics are! Then they’d be sorry! Yeah right. Fantagraphics has always felt the rules don’t apply to them; they can put out public domain Simon & Kirby collections and not pay royalties and their PR rep can be biased and operate under a conflict of interest promoting their own significant other’s work over other creators under the Fantagraphics umbrella. A sucker’s game indeed.

Wis,

Yes, everybody knows Jacq Cohen promotes her husband’s work more than any other artist and it was only until they got married that he had any success at all. Until then, nobody had ever heard of him. And if it wasn’t for her giving him ALL of fantagraphics resources, and none to anyone else, he would be nobody and all those underselling cartoonists would skyrocket, because we all know the only thing getting in the way of success for art comics is PROMOTION. Get a fucking grip. Talk about groping around for something whine about, good grief. There are legitimate worthy complaints about Groth and Fantagraphics, but your’s aren’t them. Gary never gave a shit about mainstream success-he was interested in ANY sustaining audience regardless of where it was or it’s size. There’s a big difference between that and what your saying, ding dong.

my main complaint with WE TOLD YOU SO is not enough Dennis Worden and Frank Thorne.

Wis,

I agree with Sammy that attacking Simon/Jacq is not a strong approach to take in criticizing fantagraphics. We should all celebrate that comics have the ability to get someone laid. Furthermore, I’m not not sure how many people view fantagraphics today as an entity to any degree concerned with morality, since publishing, advertising and editing seem to be occupations based entirely on arbitrarily personalized preferences. Hopefully Sammy will tell us what he thinks the “legitimate worthy complaints about Groth and Fantagraphics” are and we can all use those to accomplish our goal.

Also, I think this whole thread should return our focus to some of the really strong points I made in my earlier comments

I’m amazed that 40 years later Fantagraphics still causes such indignant outrage. Good lord. I thought only white men over the age of 50 still cared.

Skrillexfan (why would anyone use that handle?) and, uh, Wis:

Like Sammy, I agree that there are many legit complaints one could lodge about Fanta, some of which I’ve written about just recently on this very site and told Gary as well. I think that the history books are sometimes suffering from poor editing; I think the advertising campaign around the superhero books is, at best, socially, morally and aesthetically insulting. But whatever! I don’t let that spill over to my enjoyment of Joe Daly’s work.

But you’re talking about the company ignoring younger creators, and that’s just false. Fanta is publishing more young cartoonists per year than any other publishing company in the world right now. Do I think it’s all good? No, of course not. But it’s a fact. And why in heaven’s name wouldn’t a company the size of Fanta have good signage at a trade show or convention? That’s just good business.

Of course no one expects a young (20? 15?) person to know the history of the company, but at the same time, that’s what the book is for (as well as various looks back on this site). It’s a book that is, as Sammy notes, short on some people and long on others, but is hardly makes anyone central to Fanta look good! And before you say it, the title is transparently ironic. I know, irony is a hold over from the 90s. But so are many of us. Honestly, why would anyone, in 2017, “hate” a publishing company as diverse in its offerings as Fantagraphics? I don’t love it (I don’t love any companies) but it beats the hell out of anything else out there.

And finally, the idea that a publicist would have a “conflict of interest” is just silly. Publicity is all about conflicts of interests! I’ll chalk up that weird obsession to inexperience in publishing. As has been the case for the last few decades, a lot (but not all) of the rage against Groth, TCJ, etc etc is internal to the person raging. It means you’re investing this company, which you know little about, and a person you know even less about, with far more power than they have. It’s a publishing company, not an empire. If only you knew how little money and power is involved. Oy vey. It’s small stakes. It’s great art and it represents a few life’s works, but it’s still, as anyone there would admit, small stakes in publishing.

And finally, Robert Stanley Martin, says: “That’s why I doubt that Last Gasp, Fantagraphics, and Taschen are all publishing Crumb work from Weirdo on a non-exclusive basis. I would expect that one of them has signed a license with Crumb for exclusive control of the publishing rights. The other two would be including portions of that material in their projects with the first publisher’s permission. I don’t know for sure in this instance, but that’s usually how these situations work.”

Actually, that’s exactly NOT how these situations work in independent, artist-centric publishing. That’s how it might work with a licensed property (I don’t know), but in the case of someone like Crumb (or, hell, we can use my own output as an example), he and his agent control the rights and can sell them non-exclusively if they please. It wouldn’t make business or creative sense to leave it all with a single publishing entity. The publishers know (as I would know as a publisher) that you make the book you make, and sell it based on Crumb’s “brand” not on exclusivity.

That’s all! Happy new year.

Dan–

While Crumb and/or his agent CAN offer the rights to a specific effort or efforts non-exclusively, a publisher who isn’t a fool is extremely unlikely to publish the effort(s) if the publisher does not have exclusive rights, including approval for permissions. The reason why is publishers, unless they have a business death wish, want to make money from their publications. Entering into a publishing situation where a competing edition of material can be allowed into the marketplace regardless of your interests is self-destructive. A competing edition means your edition is that much less likely to make money for you.

Publishers are often willing to grant permission for selections from the material they control if it is for a project that is not in direct competition with their offerings. An example is Alice Munro and Random House. RH can and does authorize the use of individual Munro stories to various anthologies, including the PEN/O. Henry Prize and Best American short-story annuals. The assumption is that people are not buying those anthologies strictly for the Munro work–it makes up a small fraction of the publication’s page count–and the inclusion helps promote Munro’s work to readers who have not previously taken an interest in her writing.

The all but certain reason why you haven’t seen, for example, RandomHouse/Pantheon and Drawn & Quarterly editions of Ghost World, is because Fantagraphics has exclusive book rights to the material. I seriously doubt it’s because Daniel Clowes and his agent have decided to be nice to Fantagraphics and chosen not to license the material with competitors.

I’m sure similar reasons are behind why Fantagraphics, despite a decade of promising, have yet to release a Complete Crumb volume featuring Crumb’s Hup! material. Last Gasp, not Crumb and his agent, most likely holds the rights to that work, and they’re not willing to grant permission for a competing edition at least until they sell out their inventory of the original comics.

As I recall, Dan, you went out of business as a publisher. Could your “artist-centric,” non-exclusive philosophy of publishing have been a contributing factor?

Dan,

Thank you for your response

I should have clarified that by “young” creators I was specifically envisioning a unpublished creator under the age of 25. “Straight out of Art School”. A debut similar to Dash Shaw’s “Bottomless Belly Button” was what I’ve convinced myself Fantagraphics are uninterested in replicating on a regular basis. Of course, pointing this out doesn’t really disparage Fantagraphics in anyway since no publishers are giving away debuts of this nature on a consistent basis.

All the artists in the SPX panel “Fantagraphics Next Wave”, (Anya Davidson, Benjamin Marra, Noah Van Sciver, Simon Hanselmann, and Julia Gfrorer) are very cool. “We Told You So” is cool as well. But both of these “waves” translate very clearly to an artist my age as defining the limits of my value. I’m glad I’ve remained anonymous through all of this, as I’m quickly starting to understand insulting my distorted expectations must be to these creators who have labored many years. This might have been the end of my career.

My recollection of conversations with Gary about the negotiations with Harvey Pekar about including American Splendor material in The Complete Crumb, which are only as good as my recollection and should not be taken as gospel, anyway my recollection is Gary told me he kept asking Harvey until Harvey said yes, and then he didn’t ask him any more. My distinct impression was that the negotiations were with Harvey directly and not any third party.

Subsequent to the previous posting I recalled an occult method of divination known to the cognoscenti as “Looking at the Copyright Page of the Book.” There I find that the publishers thanked Harvey Pekar for giving his permission to include the American Splendor material, and the matter is identified as being copyright Harvey Pekar and Robert Crumb. There is no notice of any other publisher giving permission to use the material.

The notice on Taschen’s recently published Crumb Sketchbook Volume 1 says that it’s copyright Robert Crumb 2014.

Copyright pages have been known to contain errors, and since Fantagraphics does not file copyright registrations for their publications as a rule, you cannot verify that claim with the Copyright Office.

However, when I go over and check the Copyright Office’s database, this is what I find. All issues of American Splendor are copyright Harvey Pekar and only Harvey Pekar. No copyright registration was filed for the first Doubleday collection, although a registration was filed for Crumb’s introduction, which is copyright Robert Crumb. The registration for the second Doubleday collection says it is copyright Harvey Pekar and only Harvey Pekar. Four Walls Eight Windows did not file registrations for their editions. Ballantine’s Best of American Splendor anthology is copyright Harvey Pekar and only Harvey Pekar. According to the copyright office, Pekar claimed exclusive copyright to the material, and those claims were reaffirmed on multiple occasions. There is not a single instance on record of a shared copyright between Harvey Pekar and Robert Crumb.

Robert Stanley Martin: You switched topics and tacks, so I don’t really know what else to say other than to point out a few things: Arguing about contracts you have never seen is futile at best. Speculating about the business practices of artists and publishers is equally futile, since you have no experience in the field. I will note, however, that contrary to your ad hominem quip, I did not “go out of business”. PictureBox is not releasing new books, but the backlist is active, as are royalties. The web site is quite clear about that. When I referred to my own output I meant as an author of multiple books and essays published by different houses, galleries, and museums.

Oy! What a waste of time. I am embarrassed that I even engaged the trolls. I’d almost forgotten that attempting to deal in a good faith, factual manner with trolls like RSM is…interesting. Sorry everyone. I’m going to close this thread down because I think it’s spiraling into a classic black hole of silliness.