From The Comics Journal #247 (October 2002)

Donald Rooum is a London-based cartoonist whose work has appeared in a variety of UK publications, ranging from Private Eye and the Daily Mirror to the Spectator and Peace News. In the 1960s and 1970s, he generated a steady stream of gag cartoons and a fair number of editorial cartoons while supporting his family as a typographer in the advertising industry and later as a lecturer in typographic design at the London College of Print. From the mid-1970s onwards, he shifted over to the comic-strip format, although he reverts back to the one-panel cartoon from time to time. To date, Freedom Press has published five slim compilations of Rooum’s Wildcat, a lively comic strip that has appeared in the pages of Freedom, the anarchist newspaper, for the past 22 years. Any one of the Freedom Press volumes would serve as a credible introduction to one of the lesser-known greats of the graphical left.

In the case of Rooum it would not make a great deal of sense to try to disentangle his politics, and his broader intellectual perspective, from his cartooning. He became a cartoonist not only because he displayed an aptitude for it but because it afforded him a real degree of freedom to express his point of view. At the same time, his perspective is by no means narrowly political. He has an easy laugh, both in person and on the page. He frequently makes fun of his own characters, even his personal favorites, and loves nothing better than to affectionately lampoon their opinions and behavior. He is a fan of the cleverer varieties of cartooning slapstick, and he is an enemy of cant. Rooum does not want to convert you, or even incite you, but to make you think and chortle, not necessarily in that order.

In 1886, the famous Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin moved to Britain and helped launch Freedom Press, which continues to operate out of the East End of London. The Press is an all-volunteer operation that keeps roughly 60 books in print, including Rooum’s. For many years the Press has been based in Angel Alley, a few yards from the Aldgate East tube station, where they maintain an excellent bookshop. (Angel Alley is quite unobtrusive, and if you have reached Osborne Street, you’ve gone too far.) Freedom Press’s website is a little murky in places (what’s with the map?) but nevertheless provides a web-based introduction to the history and politics of the Press. The site includes samples of Rooum’s strip, as well as a short article by Rooum on “The Use of Cartoons in Anarchist Propaganda.” Wildcat, both the character and the strip, has clearly become a kind of mascot for this wing of the anarchist movement, but at the same time, it is very much part of a larger presentation of ideas.

The bulk of this interview was recorded in March 2002 in a café in London’s East End, half a block from the Freedom Bookshop, where Rooum regularly puts in time as a volunteer. In preparing for the interview I benefited from the insights and assistance of Guy Lawley, who knows more than most about postwar British cartooning. Needless to say, interviewing Donald Rooum was a terrific experience, and I look forward to many more years of Wildcat in the pages of Freedom, not to mention in paperback. Salut! — Kent Worcester

[This interview was copyedited by Mr. Worcester and Milo George.]

KENT WORCESTER: Where were you were born and where did you grow up?

DONALD ROOUM: Very good. I was born in Bradford in 1928, which makes me 74 next month. We were working class. We weren’t poor. My father had a highly skilled and responsible job as a machine metal worker in the bus depot. He got three pounds 15 shillings a week. This was not a bad wage, because most people in continuous employment got less than three pounds a week, and unemployment insurance paid 15 shillings a week. So it weren’t bad. But three pounds 15 shillings a week was less than what white-collar employees made.

I received a scholarship to attend Bradford Grammar School. My fees, books and school uniform were all paid for by the local authority. I generally did quite well on school exams, but when it came to the sixth form — I was about 16 years old — I became rather distracted, especially by anarchism, which attracted my interest. I got my degree, eventually, at the age of 51. A first-class honors in life sciences from the Open University.

What made you receptive to anarchism as a teenager?

I don’t know. What makes anybody receptive to anything? I found the idea of anarchy, of a society without absolutely no restrictions — for anybody, not just for me — very attractive. The first time I came across it was through Communist propaganda. For a period of about four weeks, I belonged to the Young Communist League, where I learned about the final stage of the Communist program. I was 16 at the time.

I didn’t like the earlier stages of the Communist program, which was to seize power and hold on to power for as long as it took for people to become so interdependent that the state would wither away. I didn’t understand why the state wouldn’t hold onto power indefinitely. I was told I wanted to have the free society without the revolution.

But I didn’t see it that way. Progress toward anarchy should start off in the direction of anarchy, not in precisely the opposite direction. I also came across anarchism the same year in a radical bookshop in London. There were anarchists in Bradford, but I didn’t meet them until much later.

What about your parents?

Ah. My father was a member of the Labour Party. He went to a leading member of the local party he trusted and told him, “My lad reckons he’s an anarchist.” The Labour Party member said, “Encourage him, my friend. All the top people in the Labour Party were anarchists of one kind or another when they were younger.” [Worcester laughs.]

My father became interested in some of the books and pamphlets I brought home. After the war, he was supportive of the idea that the Germans shouldn’t have to pay reparations. He went to the local trades council and read out an article from Freedom, or War Commentary as it was called, about how it wasn’t fair to prevent the Germans from rebuilding their economy.

How soon after you first met anarchists were you speaking about anarchism from street corners and Hyde Park Corner?

Well, before that I was conscripted into the army, in 1945. After initial training, I was given a political rating as an anarchist, which meant I couldn’t be posted abroad. So I spent most of my army career in a transit camp for married families. When the British had to withdraw from Egypt and India, they brought home a lot of soldiers’ families who were entitled to accommodation. They put them in transit camps, and I worked in the kitchen at one of the camps. It was very unlike anything to do with the army, apart from the level of pay; there was one parade a week and military uniforms were optional, except we had to wear a cap and salute an officer. Very relaxed from an army point of view, and I quite enjoyed it. All the English soldiers at the camp either had political ratings or psychological ratings, which also meant they couldn’t be posted abroad. The army never gave me a pension, but it did pay for my art-school education. After I left the army in September 1947, I studied commercial design at the Regional College of Art, Bradford for four years.

While I was at art school, I spoke at Market Street, Bradford.

Tell us what it was like to be an open-air speaker for anarchism.

Well, in Bradford there were all kinds of open-air speakers. I got on quite well at first, but I had to give it up eventually. I was physically attacked by elements in the crowd, by a group of Roman Catholic students. I managed just fine at the beginning when I told them that there were Catholic anarchists, but eventually, they were determined to stop me from speaking. I also spoke on anarchism on street corners in Liverpool.

Did you enjoy speaking at Speakers Corner in Hyde Park?

It was fine when I was doing it. It was very good. People went there on Sunday afternoons for entertainment. They went around the speakers to find out what was going on. The best speakers were, in fact, professional entertainers who made their living as speakers. We had one or two speakers who were as good as the professionals.

Would you also sell anarchist newspapers?

You weren’t allowed to sell in the park, so the newspapers had to be sold by the front gate. In Bradford, I was informed by the police that I was in danger of being prosecuted for calling out “papers for sale” from our soapbox on a Sunday. So I would say that anyone who wanted a copy of our paper should talk to Albert, my friend in the crowd. The police then couldn’t do anything.

Were the police monitoring this sort of activity closely?

Oh, yes. But they were mostly involved in checking up on illegal aliens.

Were the Communists friendly or hostile to anarchist speakers?

They didn’t speak on outside platforms. They were hostile but more or less regarded the anarchists as nuisances rather than enemies.

GETTING ARRESTED

Tell me again about the demonstration in July 1963.

The King and Queen of Greece arrived in Britain for a state visit a short time after fascist military officers had staged a coup with support from the monarchy. On the first day of the protests, my girlfriend went out while I did the babysitting. She was among the picketers at the hotel where the Greek royal family was staying. There were also supporters of the monarchy, but not so many. The Queen of Greece went out on the balcony first and was booed, then the Queen of Britain went out on the balcony and she was also booed. She was so shocked she practically fell down the stairs.

I went to the demonstration the following day, and after carrying a sign against the Greek dictatorship, I started to walk away and that is when I was arrested. The officer said, “Right, son, that’s it; you’re nicked.” Having been arrested, I sat at the door in the detention room and tried to listen to what I could outside. I heard one of the police officers saying, three or four times, the same words: “I took this stone out of his pocket.” I had just read a book a week before on forensic science, and I knew that if a stone had been in my pocket it would have left traces, and there had never been a stone in my pocket. I knew I had a case if I could show that the suit I was wearing had not been tampered with after the demonstration.

The police made two big mistakes. The first was that they kept me overnight in the holding cell so that there was no doubt about the suit I was wearing. The other was that the police never put the stone in my pocket. They had plenty of opportunity to do that, but they didn’t do it. When my solicitor gave the jacket to a distinguished forensic specialist we were able to show in court that the pockets had never had a stone in them. This not only led to my acquittal but to a public inquiry, which received an enormous amount of press coverage at the time. A string of convictions from other demonstrations were overturned as a result of this case.

Did the publicity help promote the anarchist cause?

It often happens that journalists avoid using the word anarchism because it is so confusing. It’s not any plot against anarchism; the word is used in so many different ways. When Freedom Bookshop was firebombed by a neo-Nazi group in 1993, the television news referred to it as a radical bookshop.

Was science one of your first loves, along with anarchism?

I don’t think it was. My interest in science came about when I was a young adult after I had been involved in the movement for a few years. My interest was sparked in part when I realized that so many anarchists were anti-science.

When did you become a pacifist?

Well, it depends what you call a pacifist. Anti-militarist is my view. Obviously, you don’t go to war for the government if you are an anarchist. I am not a principled pacifist; I’m a pragmatic pacifist. There is no point in violence because it does not get you anywhere. There are circumstances where principled pacifism does not make sense. For example, the case of the overthrow of Ceausescu in Romania was a place where mass violence was successful and useful. So I’m not a pacifist, I’m a person who prefers peace.

Did these distinctions get you in trouble when you were doing cartoons for Peace News in the ’60s?

Oh, no. The slogan of Peace News then and now, is “for non-violent revolution.”

INFLUENCES

What are your artistic influences? Were there cartoonists you wanted to emulate when you first started out?

The cartoonists I most admire are the British cartoonists who worked in comics from about 1900 to 1960 or so. These cartoonists are the most amazing artists, who worked anonymously and illustrating extremely feeble jokes in children’s comics. They are really magnificent graphic artists — Reg Parlett is one of them, Roy Nixon is another. I’m also a big admirer of Leo Baxendale. Of Baxendale’s generation, I also very much like Ken Reid. He was a neurotic and a slow worker — he only did one page a week and it took him 50 hours. Of course, he was paid by the page, not by the hours he worked. Baxendale was capable of doing ten pages a week. He was fantastic.

All of these people have in common the fact that their work appears in cheap, newsprint form and that their artistry can be appreciated by anyone.

Anyone who bothers to look at it. Some people still have a snob idea that these cartoonist-artists worked in comics, and that therefore they cannot be good artists. The same is true of the Superman comics and things like that. People don’t recognize the technical competence and even technical brilliance of some of the artists. Anyway, those are the people whose work I admire. Furthermore, those are the people whose work I study. Working now is a man called Hunt Emerson. Do you know his work?

Sure. The Journal loves Emerson.

So they should. Now he’s working on the Fortean Times. I have taken out a subscription to Fortean Times just so that I can see the work of Hunt Emerson. I draw the line at taking a subscription to Fiesta, the porn magazine, where Emerson’s cartoons also appears. I’m all for pornography but in the case of Fiesta, every photograph’s a kind of gynecological diagram. It’s quite boring and it doesn’t turn me on at all. It’s very strange. I wonder who it does turn on.

You’ve referred to Steve Bell [of the Guardian] as one of your favorite cartoonists.

When I’ve got to do a caricature of a politician I look to see what Steve Bell has done, and so does everybody else. Recently, I’ve copied the symbol he’s got for the eyes of President Bush. These things matter, of course. Cartoonists tend to copy from each other when it comes to capturing the looks of politicians and other public figures. The symbols they come up with, whether an exaggerated nose, or a low brow, or deep jowls, don’t have to look much like the real person. But once they get established they become fixed in the minds of the public. My triumph, when I was a cartoonist for Peace News, was to devise a symbol for Henry Brook, a Conservative politician who was Home Secretary at the time. All the other cartoonists used my symbol, and I thought “Right, I’ve done one.” He looked like a halibut.

One of the things that strikes me about people like Baxendale and Emerson is their anarchistic quality. Not necessarily in a capital-A sense but in that sense of being rebellious, sarcastic and generally disrespectful toward official society.

Yes. Baxendale, since his eyes have gone, has written a book called The Encroachment, which is an anarchist book. Emerson is also consciously rebellious. He also regards himself as part of the underground-comix tradition of people like Robert Crumb.

Did you relate to underground comix?

Not particularly. I did look at some of the underground comix at the time and I pinched one or two of their jokes. There’s a cartoon in the first Wildcat book that features a magistrate with a rubber stamp that reads “oink.” That was pinched from an underground comic. I forget which one. I did work on one underground comic; I got one page of Wildcat in one of the five issues of Anarchy Comics, published by Jay Kinney. One of my daughters was working in California at the time and I asked Jay to send my free copy to her since she was relatively close by. They did, and she wrote back to me and said: “yours is by far the best thing in it.” I don’t entirely disagree with her. Very varied work in the underground comix.

There were a small number of artists who were really quite good and then a sharp slope downward.

It’s just my age. I go for the Freak Brothers. I don’t collect Robert Crumb, but I do collect Gilbert Shelton. I especially like Art Spiegelman’s work from the underground. But he couldn’t work on that basis anymore; some of those backgrounds must have taken him days.

You mentioned off the tape that you once owned original art by Phil May and George de Maurier, both artists whose work appeared in Punch magazine in the 19th century. Are you a fan of early Punch?

I’m a fan of all the famous names — Edward Linley Sambourne, Richard Doyle, Archibald Henning, John Tenniel, as well as May and de Maurier.

The early Punch is said to have been much more interesting, less reactionary publication than the magazine we all remember.

Yes, it started out like Private Eye and was critical of the establishment. All the writers in the early years were published anonymously, just like Private Eye.

Which allows for a greater level of Freedom.

Yes. Although sometimes readers are able to figure out who the author might be. In the case of Private Eye, I can usually tell, for example, when an article has been written by Paul Foot, the Trotskyist journalist.

While Foot may be a Trot, you can at least say he’s done good work as a campaigning journalist.

Absolutely. I admire the work of Paul Foot. And in the case of early Punch, one of the contributors whose work appeared anonymously was William Makepeace Thackeray, who wrote Vanity Fair.

Do you want to mention any other influences that are outside of cartooning? Any film directors or novelists you would like to mention as having helped shaped your work?

No.

POLITICAL AND GAG CARTOONS

When did you start drawing cartoons?

I suppose I drew cartoons from about the age of 12 onwards. The first cartoon I published was when I was an art student. The first cartoon I published commercially was in the Daily Sketch, in 1960. From then on, I was producing cartoons fairly frequently. I published quite a few in the Daily Mirror. I was offered the job of political cartoonist for the Spectator at around the same time I starting doing political cartoons for Peace News.

What made you a plausible cartoonist for the Spectator?

The Spectator was a Conservative Party magazine but at the time it was a liberal-leaning Conservative Party magazine. They were not ashamed to publish articles from different viewpoints. So I took the mickey out of the politicians. Mainly the Conservatives, because they were in the government at the time.

How much did the Daily Mirror, or the Spectator, pay its cartoonists in 1963?

Daily Mirror paid nine guineas [nine pounds and 45 pence]. I forget how much the Spectator paid, but it was less. Peace News paid me 30 shillings [one pound and 50 pence]. At first, they paid me on spec, but after a while, I asked to be put on staff, and I became their staff cartoonist with a regular spot in the magazine.

You also published cartoons in She, which I can only assume is a magazine for women.

It’s a women’s magazine. I gave them my rejects from the Mirror. She only paid two pounds for a cartoon, a ridiculously small price. But since they had already been rejected elsewhere, I wasn’t too bothered.

What sort of cartoons would you offer them?

Simple gag cartoons. Two explorers running away from a charging rhinoceros, and one of the explorers is saying to the other, “There’s no need to worry, they’re almost extinct.” [Worcester laughs.] Thank you.

Should I assume you prefer to do political cartoons to gag cartoons?

I liked doing gag cartoons. The reason I gave up doing gag cartoons is that I was not able to make a viable career at them, even though I tried to make a go of it for a couple of years in the 1960s.

1979 was the last time I published one in Private Eye. Part of the reason I gave up doing gag cartoons is that it paid very badly. It would have paid well if everything I produced had been accepted. But only about one in six was accepted by Private Eye, and it was a lot of work. Also, you don’t have anything to fall back on with gag cartoons. In comic strips, you have a fixed setting, but with gag cartoons, you have to create a new setting each time.

Private Eye is a legendary publication, but most Americans won’t have heard of it.

Private Eye is against the establishment, whoever the establishment is. Apart from the cartoons and letters and so on, they have pages and pages with news about farming, education, the financial markets and things like that. They are always looking for scandals. And they are very good at it.

Did you take your cartoons to Private Eye directly? Did you get to know some of the writers and editors?

Oh yes. I started off by sending them through the post but later got to know a few people. They recently published a collection of Private Eye cartoons, going right back to the beginning of Private Eye up to the present. I’m not in it, despite the fact that for a time I was in Private Eye quite frequently.

I was invited to their parties, but they were all quite pointless. Somehow the celebrities that showed up did not mean anything to me. I was recognized and known as a cartoonist, but I was doing cartoons as a sideline. The editors of Private Eye were making a living at what they were doing, and I wasn’t.

But you toyed with the idea of making a living as a gag cartoonist.

Yes, by selling cartoons but not by giving up work. By the time I was getting my first cartoons accepted, I had two little girls. I had to have a steady income, and so I produced cartoons and whatever other artwork I could in my spare time. At one point, in fact, I filled in as the artist for General Nit and His Barmy Army, which was a regular feature in the British comics magazine Wham!. I forget precisely how that assignment came about, but General Nit was a Leo Baxendale invention and I suspect Baxendale had something to do with it.

What was your day job?

I started out in the advertising field. I started out after art school as a layout artist, but where I made my mark in the advertising industry was as a typographer. After 12 years as a typographer in advertising, I became a lecturer in typographic design at the London College of Print. I retired in 1983. I was only 55 years old. The Inner London Education Authority sent around notices inviting people to retire early by offering a special pension. It wasn’t a fixed pension; you had to write a letter to the Authority explaining why the Authority would be likely to benefit from your early retirement. I wrote and told them that the Authority would benefit mainly because I had been 17 years away from the industry and they would do better by getting someone whose experience was more recent.

And unlike some of your colleagues, you knew what you wanted to do with your time. You weren’t wrapped up in your identity as a teacher.

Yes, there were things I wanted to do. I was always an anarchist and a cartoonist. But I was also interested in studying the life sciences. Just before I retired, I completed my undergraduate degree. I then asked if I could have time off to study for a higher degree but they said no. I looked into the possibility of studying for a doctorate on a part-time basis. But it was just impossible. All the people that I spoke to could only think of doctorate studies as a full-time job. You can, of course, be a full-time post-graduate student and at the same time do one job. But you can’t do two jobs. You can’t be the Freedom cartoonist and the Peace News cartoonist and a full-time graduate science student and a full-time lecturer. So when I retired, I knew I would not have the money to be a full-time student.

WILDCAT

How did you come to create a strip about an anarchist cat, a “wildcat?”

The term “wildcat” has a long history in the anarchist movement — in the United States it refers to spontaneous, unofficial work stoppages, and in the 19th century there were various labor and anarchist newspapers with the title “wildcat.” Someone came up with the bright idea of starting a new radical paper with that same title in the mid-1970s, and they also came up with the idea of including a comic strip with the same name as the paper itself. The original comic strip was done by somebody, whose name I won’t mention, for about three issues and then they sacked him and asked me to take on the strip. So I contributed cartoons for about seven or eight issues in the late 1970s.

Did this early Wildcat look similar to the Wildcat of today? Or did you create an entirely different strip when you started contributing strips to Freedom in 1980?

There are a few similarities but some differences as well. I introduced the Wildcat character in the first strip, but her personality was not quite the same. At first, I visualized Wildcat as a little boy, but when I got into the whole thing I wondered how I could introduce a female into the strip. And the obvious way was to turn the main character into a female, so we did that. She looked like a little boy in the first strip, but she grew up to become a young female cat.

Had you already decided at this point that you would use the strip to debate different positions within the anarchist movement?

Not in the ’70s, but from the beginning of doing the strip for Freedom, yes.

Did the strip receive a warm reception?

The editors of Freedom were quite pleased, and the readers seemed happy enough.

How many Wildcat strips have you done?

Every two weeks on average since January 1980, when Wildcat first started to appear in Freedom. If you add them up, there are over 200 strips in the five Wildcat books, and plenty of strips haven’t been reprinted.

One of the striking things about your work is its firm sense of archetypes. For example, you have this well-defined Labour Party pacifist, in sandals with a beard.

Ah, from the first book. I’ve made him Mr. Block in the latest book, from the Wobblies. It’s the same character. The man who believes in rubbish.

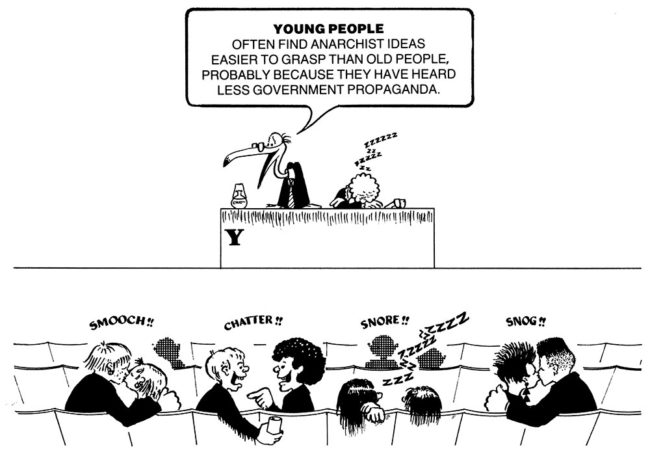

The stork, who is an egghead, and Wildcat, who is a wild-eyed activist, are both archetypes. Most of the other characters are in fact archetypes.

Ah. It’s not a stork, it’s an ibis. Quite a different matter. He’s not very much like a real ibis, but that’s what he is. He’s in most strips, of course. Because Wildcat is the main character as well as the title of the strip, readers expect to see her in every strip. But because the pussycat is in every strip she’s quite often out of character. I like to get her in character when she’s in the books.

What’s her character when she’s in character?

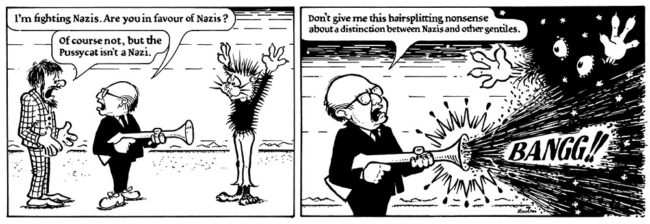

She’s an angry anarchist, without much of an intellectual basis for her actions. She knows what she wants.

There’s a sense that she will always be angry. No matter how patiently the stork explains things to her she will always be on a tear.

Ah yes, she’s a comic-strip character. [Laughter.] She’s not going to change. And then there’s the mystery character, the third anarchist.

The one who always criticizes other anarchists.

No, no — not the rat. The third anarchist, whom I refer to as the mystery character, often wears a hat. Sometimes there are three of them. The third anarchist is there when you need a third character.

On first reading, your work is very much about these archetypes and their interactions. It’s humorous and it’s educational. But there’s another theme, which has to do with the argument about reason and science.

I do get annoyed with the anti-science view. But I’m not so sure about your first premise. Most of the cartoons are about politicians going off to war and such like. It’s not usually about arguments within the anarchist movement and such like.

But you have an entire book devoted to the anarchist ABC’s.

Yes, the ABC of Bosses.

Do you get readers telling you the strip has helped them understand the anarchist point of view?

The only one I can think of is the late Tony Gibson; when he was asked about what anarchism meant, he would give the person the first Wildcat book.

Do you get readers complaining about your pro-science views?

No. I did get a couple of letters accusing me of being anti-Semitic. I did a strip about Mr. Begin accusing the Palestinians of being Nazis.

This strip suggests you received a death threat at one point from an angry feminist.

Oh, I wouldn’t take that too seriously. It’s amazing how frightening these sorts of things can be at the time. It was signed “The Black Dragons,” and I would guess the writer was 15 years old. Not to be taken seriously.

WORKING METHOD

Say a little about how you work.

I usually set aside a day to work on it. First of all, I get the dialogue right. If I haven’t got the whole dialogue I at least have the punch lines. I draw out the area, the tramlines for the lettering, and begin by lettering in the punch lines. This gives me the right-hand edge of the cartoon. Then I ink in the edges, as well as the heading Wildcat. Then I do a standard thing; I do all the lettering. The lettering decides the width of the frames. After I’ve finished the lettering I ink in the frames, and then I’ve got nothing to do but the illustrations. It takes three or four hours, after getting the main idea. Sometimes longer.

Do you ever give up halfway through?

I usually finish what I’ve started, but not always. I have started some things where I’ve thought “God, this is tedious,” and set it aside. To do a good job I hope to achieve a number of different things: I’ve got to make effective use of the set characters; make a political point; comment on something in the news; if I can, be funny where possible; and be decorative. With every cartoon, I have five aims I’m trying to accomplish.

Which do you prefer: the writing or the drawing? Which is more rewarding?

Well, to tell the truth, I like working with other writers. I like messing about with scripts, adding extra jokes and things. If somebody were to write scripts for Wildcat, and my job involved revising the script and drawing the strip I would be a happy man. I liked being a typographer in the advertising industry. What I particularly enjoyed was the challenge of working on one little aspect of the whole, the typography, in conjunction with a squad of artists. If everyone works well, we get something terrific out. A typographer can’t turn bad work into good work, but a typographer can ruin something that was pretty decent to start with.

Being a typographer must have given you an appreciation for the economy that is involved in scripting a cartoon — to ensure that every word and phrase adds to the piece as a whole.

Yes, it has to start with the writing, hasn’t it? When you’re doing a comic book it doesn’t matter so much, because you have more room to tell the story. But a comic strip, or a gag cartoon, has to be precise. At the same time, a comic strip is often called on to be decorative. In Freedom, for example, and in The Skeptic, part of the cartoon’s job is to decorate the page. It’s got to add to the visual impact of the page.

And in your case, more so than in many comic strips, the lettering itself is decorative.

That’s because I’m a typographer, so I might as well show it off.

Do you prefer the comic-strip format or the one-panel-gag format? I noticed that even some of your Wildcat strips are one- or two-panel gags.

Yes. If I can make a good joke in one or two panels then I will make the joke in one or two panels. I like to vary the pages. If I’m looking for cartoons to include in one of the books I will look for some variation in the format of the pages. If you look carefully you will see that the last book [Twenty Year Millennium], apart from the title page, consisted entirely of cartoons reprinted from Freedom. I expect the next book will consist of cartoons from Freedom as well.

Will the next book have a theme?

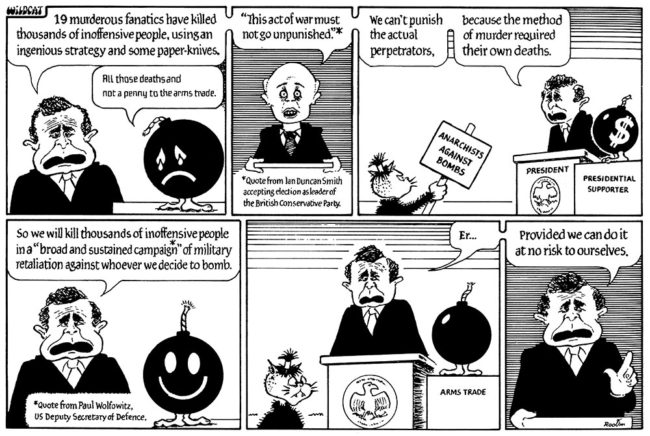

Anarchists against bombs. We’ve introduced a new character — a walking bomb. Ray Morgan bought me a little toy of a walking bomb and said it might be useful. A walking bomb represents the arms trade. It’s very easy to draw a walking bomb.

What’s the bomb’s character? What does the bomb want?

He hasn’t said anything so far. He usually doesn’t even have a face, although after Sept. 11 I gave him a face. It turned out he was very annoyed as the perpetrators of Sept. 11 didn’t use any purpose-built weapons. They brought civilian items on the planes and used them as weapons, which is a dreadful thing to do to the arms trade. Then the bomb smiles when he finds out that the U.S. and other countries are going to start making more bombs and other weapons as a result of Sept. 11.

It’s almost like scab violence, from a bomb’s perspective. It should have been a union job.

Since then, of course, the arms trade has been revitalized. Now they have an enemy that can’t be defeated, the arms trade is going like gangbusters. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the international arms trade had been going down and down and down. The arms trade should be very grateful to Al Qaeda.

Are you sorry you haven’t had the chance to do more work in color?

Not at all. I have tried color and I’m not good at color at all. If the situation required it I would ask for a colorist. Carol Bennett is a very good colorist. She has colored Hunt Emerson’s work. She’s one of the proprietors, in fact, of Knockabout Comics.

What are you currently working on?

Wildcat appears once a fortnight. The Sprite is currently appearing four times a year. It’s a cartoon that been appearing in a magazine called The Skeptic since 1987. The cartoon revolves around two characters. The first character is named Donald and is based on me, and the other character is Titania. She is a lady sprite who has a habit of disappearing into a swirl of smoke. She is in love with me, but, me being a skeptic, I have no knowledge whatsoever of her existence. The plot is based on her efforts to reach me through my skepticism. Some of the time I merely take a swipe at something in the world of the paranormal, but the best Sprite cartoons are the ones where I revert to the main plot.

![]()

One final question: Do anarchists have any reason to be optimistic these days?

Well, I have. I think any anarchist of my age must think there has been some progress over the past 60 years. Certain activities that were once considered crimes are no longer prosecuted. Take homosexuality, for example. Homosexuals are now fully accepted. We now have a homosexual police commander. Fifty years ago he would have been arrested. Also, the general attitude toward the monarchy has changed. When Private Eye first started they were very polite toward the Queen. Now, any cartoonist can be as rude as they like about the Royal Family. And that wasn’t true for years and years and years. The whole culture of deference toward authority has gone down. So that’s good news.

And would you also mention the fall of the Communist system?

[Long pause.] I don’t know. There were two great powers for 50 years, and now there is only one. I’m not sure we’re any safer.