Wisconsin Funnies is one of the best comics anthologies you might not see in stores this year. This handsome 9” x 12” softcover book is a sampler of an ongoing exhibit at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in Milwaukee. It’s a probable first for comics curation—a show devoted to a body of work from one state in America. Though some of Wisconsin Funnies’ residents are emigres, related by being published in the state, they’re connected to the pivotal figure in this show, Denis Kitchen.

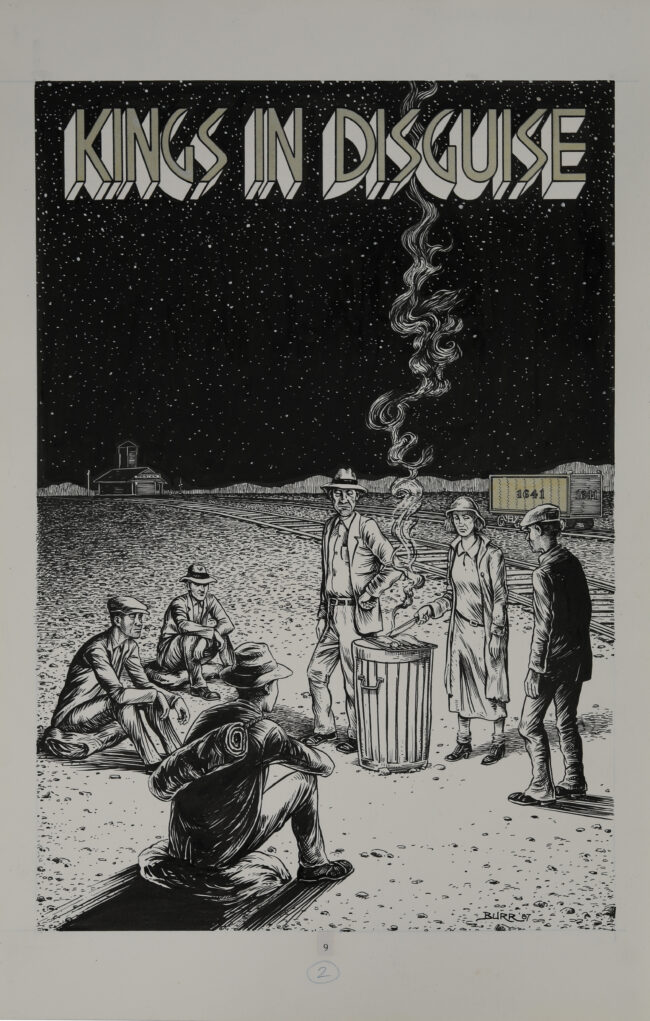

The book brings to light some cartoonists who haven’t found their way into the underground comix canon. Jim Mitchell is a stunning draftsman who’s equally adept at realism and pure cartooning. In the prime of his comix work, he spent four years in a Mexico prison for possession of marijuana. Bruce Walthers, Mark Morrison and Michael Newhall are other intriguing figures from the underground era. Dan Burr is a veteran artist whose work spans political cartooning and the gritty atmosphere of the long form Depression saga Kings in Disguise.

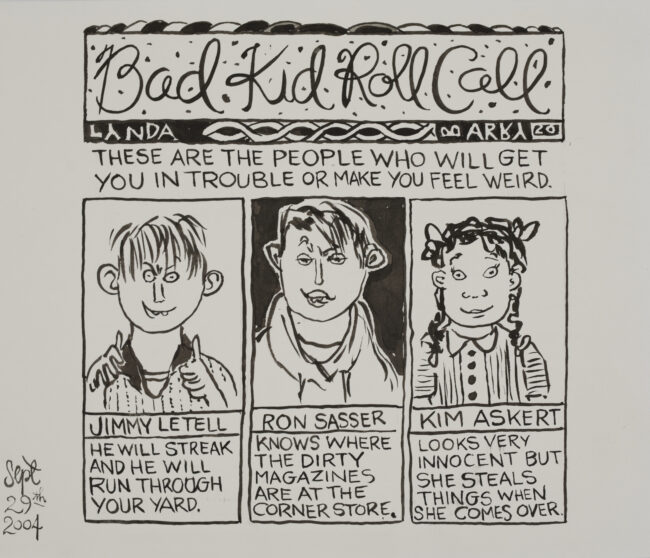

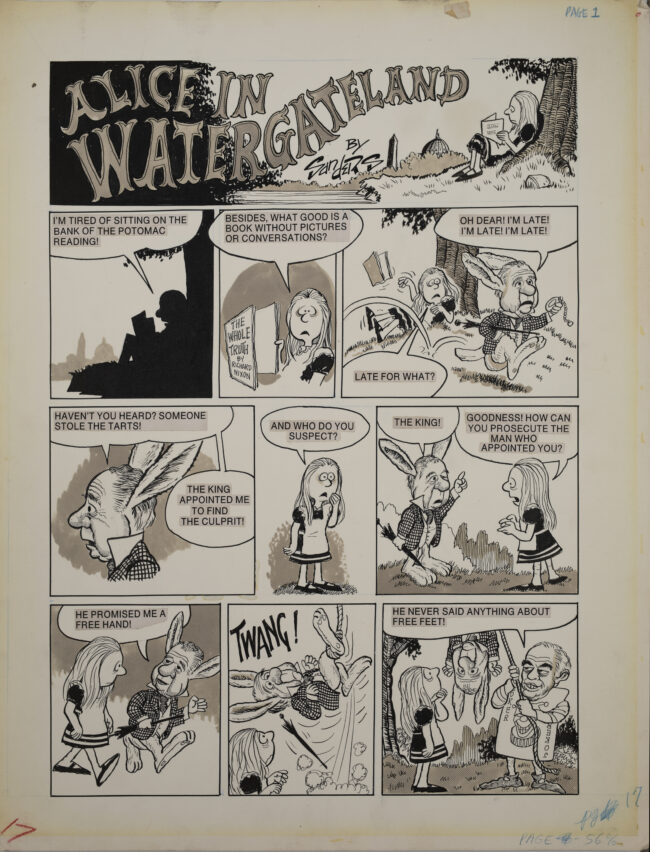

Historical and contemporary heavyweights—from Ernie Bushmiller to Lynda Barry to Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder—are here as well. Less-known selections by these artists makes the Wisconsin Funnies book more of a treat. There’s much to read here that hasn’t been done to death, and some excerpts leave the reader hungry for more by the lesser-known creators.

The modern work of Susan Simensky Bietila creates striking woodcut-influenced images in the service of autobiography, family history and political commentary. John Porcellino, whose work is as minimal as Bietila’s is dense, continues to create work that leaves a lingering spell on the reader, and collaborates with its audience, as we fill in the details in his impressionistic drawings.

Filled with handsome reproductions from original art and biographical notes on each creator, Wisconsin Funnies is a souvenir of a show few may get to see. Co-curators James Danky and Denis Kitchen, who previously teamed for an underground comix-themed exhibit that became Robert Crumb & The Underground, had no idea when they began this new show that the world would soon be confounded by a viral pandemic. In late September of 2020, James talked with me about this new show, his past adventures in comics curation and the challenges of mounting a historical exhibit in a social climate that is quick to cast aspersions on the work of the 20th century.

Frank M. Young: Take me back to the beginning of this show, and how it came about.

James Danky: In 1977, I organized a conference on book publishing in Wisconsin. I worked at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin and organized the conference with the library school and arranged for speakers from the university. I also did a directory of book publishers in Wisconsin—the kind of thing you wouldn’t do today because of the Internet.

In those days, people would get it in their head to produce a book but would be discouraged when it came time to publish it. It was difficult to get mailing addresses, phone numbers, etc. for Wisconsin publishers. I’d already been reading The Bugle-American, Denis Kitchen’s underground newspaper from Milwaukee. I did my first book Undergrounds on alternative newspapers in 1974 and been reading underground papers since the early 1960s, when Art Kunkin invented the whole genre with the LA Free Press.

I noticed that Denis had registered for this conference. We met over the lunch break and talked. He mentioned that he had a collection of comic art—not just underground, but all kinds of cartooning. We both said that it would be great to see originals of comic art on the walls of a museum.

It only took us 30 years to get it off the ground! In 2009 we did the show Underground Classics: The Transformation from ‘Comics’ with an S to ‘Comix’ with an X. We had the interest of an art museum director in Russell Panczenko, and that’s really a key. It’s not always true of people in art institutions. Of course, they know about comics, but they don’t necessarily have a love for them.

Russell kept goading us, encouraging us, and we got it off the ground in 2009. That show, under the title Robert Crumb & The Underground, was installed at the Kunstmuseum in Luzern, Switzerland for “Fumetto,” their city-wide comics exhibition, in 2013.

Denis and I have been friends for a very long time. I’m not a Milwaukee guy—I come from downtown Los Angeles—but we kept talking about this new exhibit and kept pushing it. Putting a show together requires a tremendous amount of persistence—less so this time than in 2009—because of all the protocols that art museums have and worries about expenses…it’s not that those are wrong, but they speak a narrow language that Denis and I had to learn.

Denis has done several other exhibits: he did a nice one on Will Eisner in New York, and another on Will in Angouleme. For many American art museums, it’s been a harder sell. John Carlin and Brian Walker’s exhibit The Masters of American Comics (which debuted in 2005) was an incredibly important show—all of us have learned from it. That it stands by itself is pretty telling.

Most of the comics exhibits I’ve seen have been at regional museums. The Seattle Art Museum did an inspired show, Graphic Masters: Dürer, Rembrandt, Hogarth, Goya, Picasso, R. Crumb in 2016, which concluded with all the original art for R. Crumb’s The Book of Genesis graphic novel.

And Robert Crumb said Genesis was an illustration job he did. (laughs) And although some of the imagery in that book might offend some religious people, it’s still a safer show than if you did a retrospective of S. Clay Wilson—just to choose the most outlandish example.

Our main collaborator on the 2009 show was Eric Sack, the great collector in Philadelphia. Most of the pieces in the exhibit came from Denis’ and Eric’s collections. One of the pieces we used was Wilson’s “Captain Pissgums and his Prevert Pirates.” Denis was in Massachusetts at this time, so he wasn’t tasked with doing the museum docent talk. And the demographic of museum docents is going to be older white people. I had to give a talk to them, and it was like a game of “Twister.” Although the show had controversial material, The Chazen Museum of Art insisted that they put up a small, business card-sized sign that said, “Adult Content.” Did they do that for Caravaggio, because he cuts off heads? Denis and I lived with that.

Later, I met a friend of my wife who was one of the docents. She complimented me on the exhibit, but said, “there was this one…” And then she started to stutter a little, like she didn’t know what to say. I asked her if she turned to the right as she entered the gallery. She said yes. I asked her if she was trying to describe the third piece down on the wall (which was “Pissgums”). She was amazed that I had gotten it. I said, “It is incredibly disturbing, but in my opinion S. Clay Wilson is a genius.” It doesn’t mean that he’s easily digestible…

He’s not a mainstream genius.

(John laughs) Not at all!

Although a case could be made that Hollywood action blockbusters have at least matched the level of violence in his comics.

Oh, gosh, yes! But when you mix up sexual imagery and misogyny as in Wilson’s work, those are a variety of the third rails that Hollywood mostly eschews.

In our current climate, in which the peccadillos of the 20th century seem to be on trial, there are all manner of new objections to the underground comics canon. We’re living in a time where someone seems to have hit the pause button on irony.

A lot of feedback comes from people who are very young and who are self-professed progressives. They don’t accept the idea that if you don’t like something, don’t look at it. They tend to demonize these works. It’s an illiberal moment for culture.

Did you and Kitchen face any such issues in putting together the Wisconsin Funnies exhibit?

No. Because of Tyler Friedman, our partner in the exhibit—he’s the associate curator for contemporary art at The Museum for Wisconsin Art, which is in West Bend. It was a small regional museum until 20 years ago. Then they got a huge bequest, raised more money and built a sleek building that looks like a modernist ocean liner parked on the side of the river. We’re happy to be there.

With Tyler, I did the first part of the brokering, and then he flew out to Denis’ house and spent a couple of days looking at his collection of originals. Denis and I had already determined that this was not a show about underground comix—although there’s a lot of underground art in it. It needed to cover everything.

So we have Clare Briggs and The Gumps and super-hero comics—it’s a recipe that’s not going to be improved by having, say, “Angelfood McSpade” and S. Clay Wilson. We did not offer those things up, because we wanted this exhibit to attract a broad audience. It needed to be something that told the broader story of Wisconsin comics. We didn’t see the coronavirus coming!

What challenges did that put on the table?

Denis and I are both geezers—he’s a year older than I am. And despite the fact that his mother lives in Milwaukee, Denis told Tyler, “I’m not going to get on a plane and fly there.” And I understand that.

A local TV station did a video walk-through of the show, which Tyler has posted. Paul Buhle saw that, and has seen the catalog, but he said “I’m not going to go over there. I’m too worried about being around people.”

I’m a bit more brazen. I’ve been there with my wife. We didn’t go to the opening, because that seemed to be too much, but we’ve been there once and we’re planning to go back there tomorrow with our son and his girlfriend. The only thing I ever denied him, as he was growing up, were my copies of Zap Comix. (laughs). I want him to see it; I’m very proud of the work that’s there.

COVID-19 is a terrific challenge for every museum—and institution. How are they going to do what they did in the before-times? There is no easy answer. Some people do exhibits that are only online, and I understand that. If our exhibit were being organized, say, to open at Christmas, we’d want to make sure that it had a strong virtual component. The people who want to see it aren’t just in Milwaukie, Oregon— they’re in Milwaukee, Wisconsin!

As it is, there’s isn’t a complete virtual resource set up for the show. There are local TV spots, and videos by people who’ve visited and posted about the show. Most of those are just reviews of the exhibit itself. Tyler and I arranged for a review in The International Journal of Comic Art, by an academic at UW Milwaukee.

There’s a video where Tyler walks through the exhibit in West Bend, and someone follows him with a camera. What it misses is the other part of the show, which is at the St. Kate Hotel in downtown Milwaukee. 40% of the show is down there—the more political works.

The St. Kate is part of a development of hotels that have dedicated art gallery space—not just art on the walls, but real galleries.

When I first looked through the book, before I got the story, I was puzzled by the inclusion of many non-Wisconsin cartoonists. And then I realized they were there because of Denis Kitchen.

There was a great deal of unfamiliar material to me that I loved seeing. Susan Simensky Bietila’s work is quite striking. Her story “Return of the Cossacks” is powerful.

She does all of her stuff on the computer. I don’t know her personally, but I know she is a political activist. I don’t think there are books of her work, unfortunately.

And, going back to the underground period, the story of Jim Mitchell. I’m not sure I would trust modern-day Hollywood to do it, but there’s a great movie in the story of his life…

Jim was enthusiastic about the show. He loaned things right away. He still lives in Milwaukee, as does Dan Burr; both loaned their originals to us.

The goal of this exhibit was not to be the Wikipedia of everything comics in Wisconsin. We had to make selections. So certain artists are not there—hopefully not too many of the ones that people are looking for.

The history of Western Publications, which was in Racine, could be the subject of a show on its own…

I almost did a history dissertation at UW Madison on Western, but I decided I didn’t have seven years of my life to devote to it.

Our goal was to show the breadth of work and how different artists intersect. A good example is Lynda Barry, the doyen of autobiographical comics and now the author of books that explain why you need to pick up a pen and start drawing, had Jeff Butler, creator of “The Badger,” in one of her classes. When Lynda went on leave, she asked Jeff to teach the comics course for her.

You compare their work and they’re so different—in gender and in style. But what is true is that they’re both Wisconsin cartoonists. As we were planning this show, I looked around for other examples, and I feel sure that this is possibly the first time someone has done an exhibit and a book about the comics produced in a state. You would need multiple volumes to do New York or California, or Seattle.

I hope that other people look at this and say, “We could do the same thing, because we have all of these wonderful cartoonists in Idaho.” Cartoonists—comics people—are everywhere.

And working in every stratum. I found it fascinating to see editorial cartoonists dabbling in underground comics—people crossing barriers. There’s a story about Denis Kitchen visiting a newspaper cartoonist, after he’d published his first comic book, and the cartoonist slipping him a couple of sable brushes from his art supply… (laughs)

And that cartoonist, Bill Sanders, who’s in the show, is in his 90s and is still alive. We hoped to break down some of the categories that people think are inflexible.

I think many people aren’t even aware there are comics outside the mainstream genres.

I read very narrowly in comics—mostly contemporary graphic non-fiction. I tend to read things like Jason Lutes’ Berlin. My friend and colleague Paul Buhle just had a graphic novel biography of the actor Paul Robeson. And he just got a grant to do a graphic version of W. E. B. DuBois’ Souls of Black Folks.

One of the joys of the Wisconsin Funnies book is discovering artists that I’d somehow missed before. Mark Morrison’s work is a revelation.

And right after him, alphabetically, is Michael Newhall. “Buddha Crackers…” I could stare at those pages for an embarrassingly long time!

The real spiritual thread running through this show is Denis Kitchen. And through him, you get into the fascinating history of underground newspapers. I think historians are just starting to realize this was a significant moment in American history…

I’m deeply biased, but I certainly agree!

A book could be done on the history of the Bugle-American…

It’s an important paper, and it’s almost unique in that it had a dedicated comics page.

The ‘60s seems to get visually reduced to San Francisco rock posters, which are great. And if a museum is going to have an exhibit about that decade, that’s what they’re going to show you. What’s completely disappeared are underground newspapers, and, to a lesser extent, underground comix. You can show examples of them, but it’s hard to get across how large a movement it was. Every place you went— certainly any city that had a college or university. And many had no connection to academe. They had all matter of things.

Two years ago, Art Kunkin died. Paul Krassner, who founded The Realist, died in 2019,

and just a few days ago, Ron Cobb, who was the editorial cartoonist for the LA Free Press, died at age 83. All the obituaries for Ron talk about his work in films—for E.T. and so forth. I’m hoping that sometime Denis and I can put together an exhibit of Ron Cobb’s cartoons. They’re almost all wordless, and they translate instantaneously from 1965 to today. It doesn’t have that dated feel that you can get with Thomas Nast’s work.

In any curated event—a book, a music anthology or a museum exhibit—there are pieces that become pet favorites, and pieces that wind up getting winnowed out of the collection. What artist were you happiest about being included in the show?

In some cases, it was work I hadn’t really sat down and studied. Tom Pomplun, who ran his own publishing house, Eureka Productions, did a series called Graphic Classics. I’d read some of them, but he’s done a lot of books, so I had to figure out how to access the material. Tom has had serious health problems. He was bitten by a deer tick, and as a result he lost his speech and movement. His wife Georgene is a friend of mine, and we took the computer files, which Tom still had. Tyler figured out how to put a flat screen monitor on the wall at West Bend and display the files there. It was a way to include digital files when we didn’t have the physical print material. We included works by Leilani Hickerson and Marty Two Bulls Senior from those files.

I think if I have one sentimental favorite, it would be a piece of Will Elder’s for Snarf. It’s his parody of Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa but filled with underground cartoonists. It never fails to make me smile.

In a similar vein, Peter Poplaski’s cover for the exhibit book is perfect. The caricatures of the show’s artists are spot-on.

Pete depicts himself on the left-hand side, asking “But is it art?” And his partner, Rika, who is a fine artist who does oil paintings and prints, is on the other side, answering “Oh, c’mon…it’s in a museum ain’t it?”

How did the cover image come together?

Denis and Tyler had a conversation about what the image should be, and then Pete did a bunch of alternate versions of the concept. Maria Hoey is a colorist that Denis has used in many publishing ventures, and her work makes the whole thing pop.

This was one facet of doing an exhibit of 200 pieces, in two venues—this is the first time MoWA has done that—and doing a catalog. Denis and I, when we started this exhibit, negotiated for two things. We would both be listed as guest curators, and there had to be a catalog, because we’re both print guys. That was agreed to. But I had no notion about the gorgeous, huge nature of the catalog until they sent the final files to me. They sent them on a Friday and said, “Could you proofread this for Monday?” I said “sure,” because I didn’t think it was going to be very big.

It’s a big and satisfying book, and for a person like me, who is in the wrong Milwaukie…(both laugh) It gives me a strong feeling of what the show is like. This is a ground-breaking exhibit, and I hope that his interview helps the show to get all the recognition it deserves.

It’s a validation for other museums that are considering doing an exhibit on comics, and of course for the artists whose work is there. The artists in the show who’ve seen it—or sent relatives to see the show— are very, very happy to have been included.

Someone at MoWA asked me how I liked the show when my wife and I saw it. I said that it made me giddy. I’m overly familiar with the art, although it’s great to see the originals up on a museum wall. I love comics! (laughs)

<><><><><>

The Wisconsin Funnies catalog can be purchased online at http://wisconsinart.org/shop/featured items.aspx or at the Museum of Wisconsin Arts shop. Their phone number is 262-247-2241. The list price of the catalog is $48.95.