If you’ve had any exposure to mainstream comics over the past two decades, it is almost a dead certainty that you’ve felt the effects of Dan DiDio. For 18 years between 2002 (when DiDio was recruited to DC Comics in the newly-created position of vice president-editorial) and 2020 (when he exited the company in the aftermath of one corporate regime change, and shortly preceding another), DiDio was one of (if not the), preeminent editorial architect of the DC line. Eventually elevated to the position of co-publisher alongside Jim Lee, DiDio made his reputation as the chief mover behind initiatives from the All-Star line of comics to the universe-resetting New 52 - and, in so doing, helped to set the tone, style, and frequently controversial content of Big Two comics in the current millennium.

There are two throughlines to DiDio’s career thus far. First there is a deeply-held and often-repeated conviction that gazing backward is the death knell for comics. Second is the inevitable fact that executing this conviction is more complicated, impermanent, and contradictory than it sounds. This may ultimately be the reason why, with his DC years behind him, DiDio has opted to take his next step outside the safety rails of major corporate publishing. In April of 2022, he was announced as publisher of Frank Miller Presents, a new independent comic venture spearheaded by the eponymous creator.

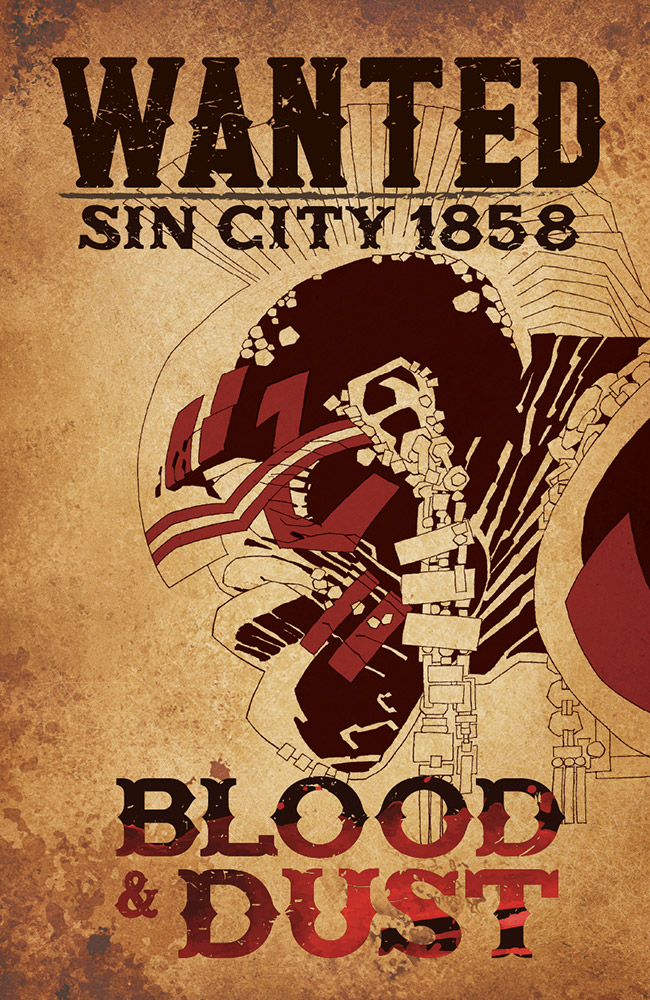

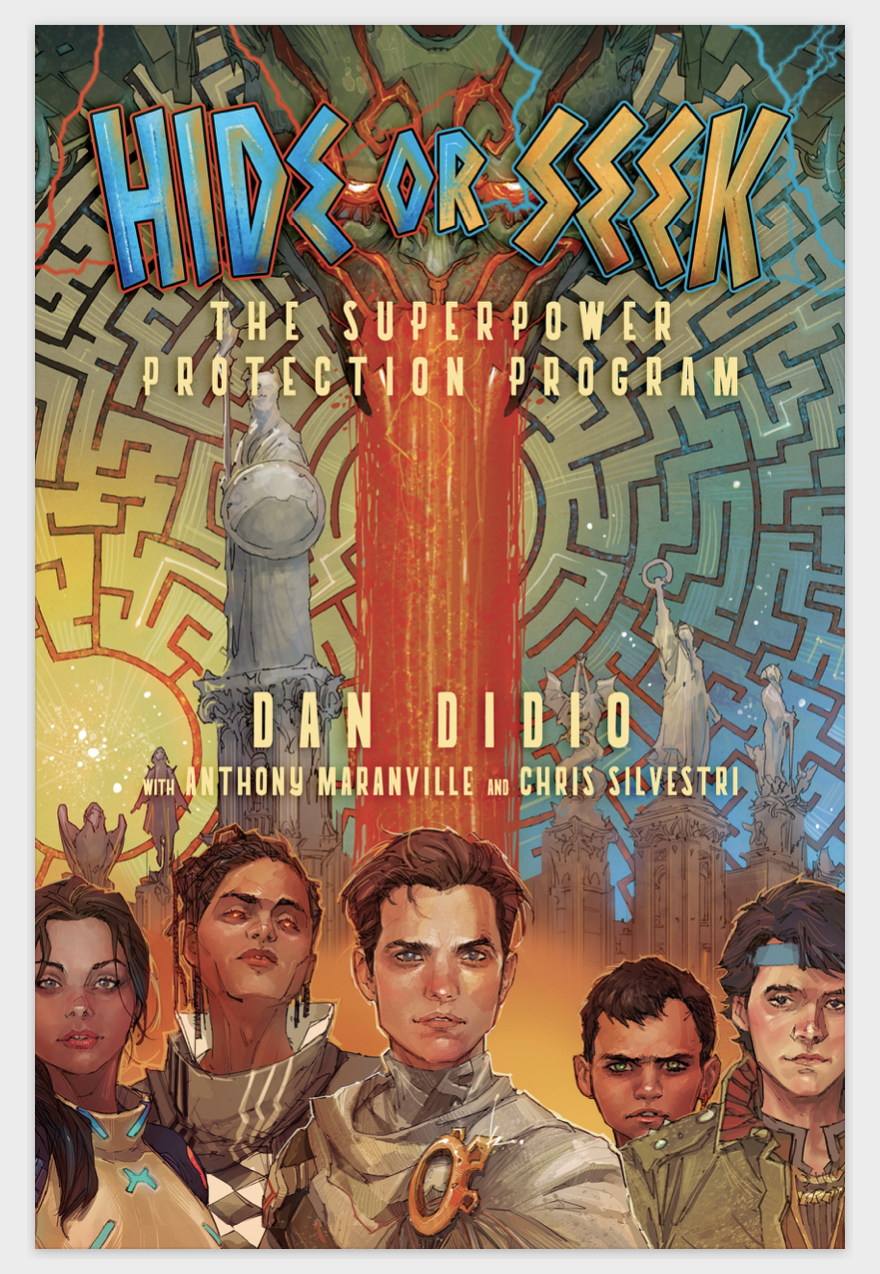

The company’s initial slate of offerings include a smorgasbord of genres from westerns (the forthcoming quasi-Sin City prequel Blood & Dust from Miller himself), YA fiction (Pandora, by Anthony Maranville, Chris Silvestri & Emma Kubert), and superhero urban fantasy (DiDio’s own Ancient Enemies with artist Danilo Beyruth). It is indeed that eclecticism which provides a certain throughline to the new company’s ethos: FMP aims to revive a spirit of craft and experimentation that, in the eyes of the company’s founders, may have been lost in the era of corporate comic publishing.

This, then, is Dan DiDio preparing to thread the needle: speaking skeptically of the long-term future of the direct market, even while once more rolling the dice within it. As Frank Miller Presents undertakes its first full year of existence, DiDio sat down with The Comics Journal to speak frankly about the nuts and bolts of starting a new publishing venture, the realities of the comic business in 2023, and where he hopes his company–and the comics medium–can go from here.

-Zach Rabiroff

ZACH RABIROFF: Let’s start with the basics about this new venture. How did the idea for Frank Miller Presents first spark, and when did you first start talking to Frank about it?

DAN DIDIO: Frank and I-- you know I worked a lot with him during my days with DC. But once I was out of the company, we stayed in touch. And we kept on talking about what we loved about comics. And Frank’s a big comic lover too: not just what he did, but the scope of the industry, and all the influence he had, and all the people who had mentored him over the years. And the conversation moved to craft and the making of comics, and we felt there was a lot of craft being lost right now.

I mean, the great thing is that there’s so many ways to make comics, and that’s wonderful. The bad news is that you can get it out there so fast, you might not be able to hone it properly and people might be picking up bad habits just to get product out the door without really developing their skills fully. And some people can learn as they go, but other people need that help and direction. And Frank talks about himself about how he was mentored by Neal Adams and other people and how much that helped him be a better artist and a better storyteller. And part of him wanted to pass that craft on.

And part of me wanted to do something different. You know, I was getting extraordinarily frustrated at DC, not because of anything other than the fact that when you're with the same company for so long, you're doing the same thing over again. You feel like you're repeating yourself; you're constantly having to reinvent a wheel. And I can honestly tell you that when I first got there, all the stories I really wanted to tell were probably told within those first five or six years I was at DC. You know what I mean? And then ultimately, you have a job to do. So you got to keep it going. You got to keep it moving. And you’ve got to constantly reinvent yourself as you go on.

And so leaving DC, I didn't want to leave comics 100%, but nor did I want to do what I was doing before. Frank actually asked me to edit something for him. I said, rather than edit, why don't we publish it ourselves? And the attraction of that was, even though I was a publisher and Frank's been in the industry for 40 years, 50 years, this is this is the first time we're ever really doing our own thing, our own company. And it was a little scary, and a little frightening. And you know when you've been around the business as long as I have, and you’re stepping into something you're nervous and scared about, that's a good thing, you know? That means you're moving into new territories; you’re challenging yourself. And the goal here was to challenge ourselves, but also stop complaining about what we didn't see in comics, and find a way to do stories we believed comics should be at that moment.

You bring up a lot of interesting points here, but one of the first I’ll start with is that Frank has been, if not self-publishing, then at least managing his own creator-owned properties for a very long time at this point. In big way, he helped pioneer that model way back with the original Ronin. So how is this different from, say, the Legend imprint he did at Dark Horse during the ‘90s?

It's our company. Literally, it's our company. We’re partners on the project - Frank, myself, and Silenn Thomas, this is our company. We're doing everything ourselves. Literally, soup to nuts. You know, picking out paper stocks, hiring everybody that we can, writing solicitation copy. Every aspect of the publishing process, we have our hands on that.

And that’s the thing: when Frank takes on the name of editor-in-chief of the company, it's not just a name he pulled out of a hat. He's going over every book. He's commenting on all the layouts. We get thumbnails, he reviews the thumbnails. He's giving active notes and participation in everything going on. Because part of what he wants to do is talk to talent, and teach and learn the same way he did. And you can see him, his eyes light up when he’s talking with people.

One of the best moments I’ve had while working on a project was Frank working with Emma Kubert. And you know, for him, it’s the third generation of Kuberts he’s working with. But we were sitting having lunch one day at one of the conventions, and they’re just chatting. And they’re both sketching on papers, and moving notepads back and forth with these sketches, and there’s something magical about that because I can’t draw. So you could sit back just in awe, and watch these people as they’re creating. And there’s just, like, the silent line: there’s that one language that’s being spoken, but there this silent language underneath it. It’s fascinating to watch.

What’s it been like getting this company off the ground, then? Have you ever been in the position of building a company from the ground up?

Never. No. I’ve been a corporate baby my whole life, for the most part, but the most independent I ever was, was when I spent one year as a freelance animation writer where I worked for a company called Mainframe - we had a show called ReBoot. I did that for about a year, and then they pulled me into the company. And for me, working for a company with 400 people was working for a small company. Now it’s four people. And it’s nerve-racking, because it’s not just about doing what you want to do, but also, you know, the financial responsibilities. But you also want to keep that independent freedom, and the ideas, and creation.

And it's a tough act to balance because of the challenges in the market. And you don't want to compromise because of expenses. You see that a lot. You don't want to compromise by using a lot of the tricks that people use to sell books these days, like variant covers. You want to believe that the content will carry the day. You want to believe that people are still reading comics, not just buying them because they think they're going to flip them like some cheap house they bought. And that's the hard part, because you want to keep on believing that. But when you're producing yourself, and you're publishing yourself as your own company, you're exposed to a lot of the realities in the marketplace. And you’ve got to balance those against your own creative needs, and it’s tough.

My goal, just the same way it was at DC, was to make sure the creators create. I want to make sure Frank is enjoying what he's doing, because at the end of the day, you know, neither he nor I have to do this. I could retire right now and be very comfortable. I'd be bored out of my mind, but I'd be comfortable. We do it because we want to do it, and because we enjoy it. And there’s a sense of accomplishment now when a book comes out that I can tell you has been greater than anything that ever came out probably in the back half of my career at DC.

So, then, let’s talk about the books that are coming out. How is Frank, and how are you, deciding what sorts of things you want to publish? And what do you feel like maybe the market isn’t seeing right now that you can add to it?

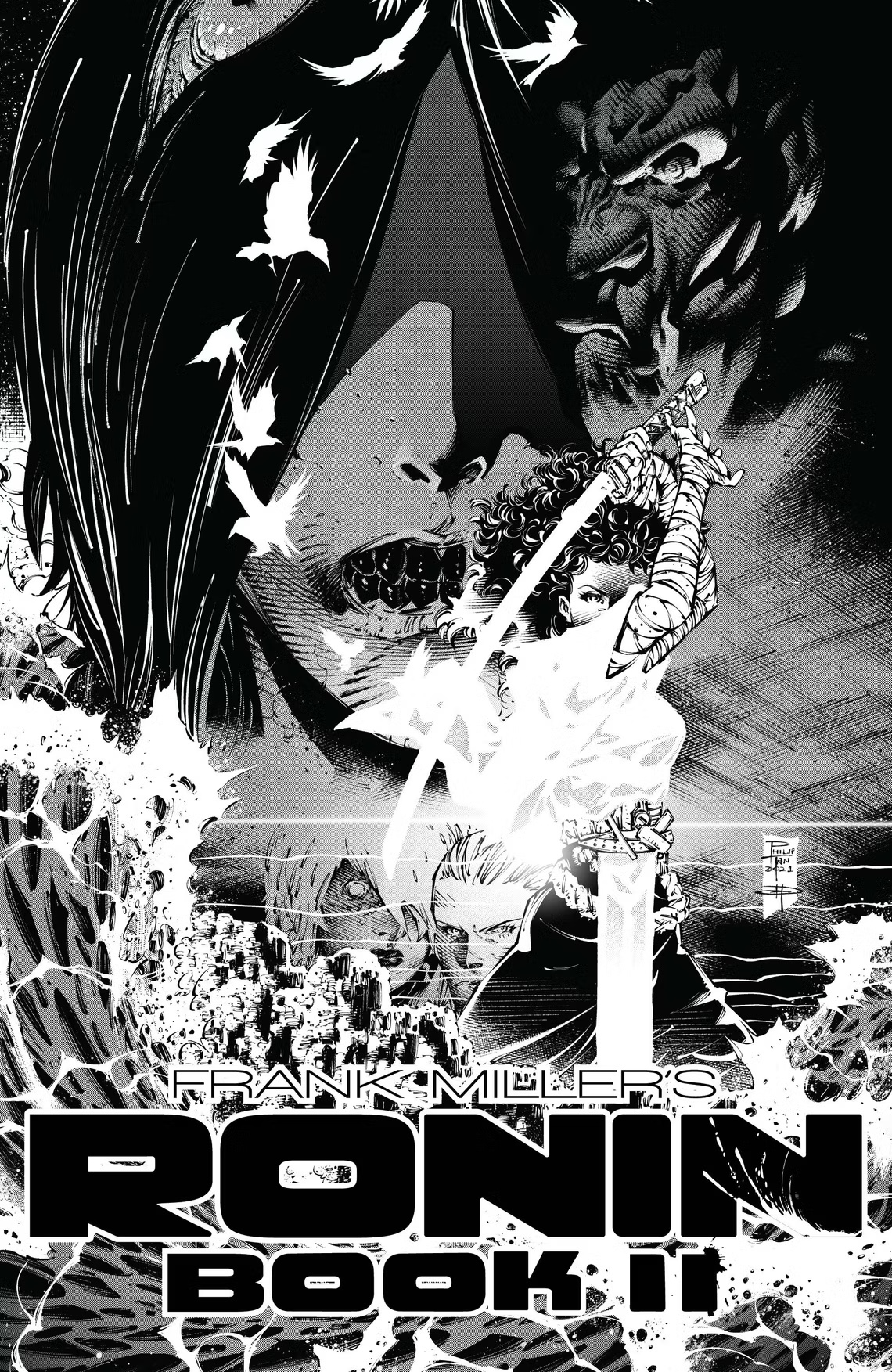

Well, it’s a two-pronged story, because we launched with a series of books that we wanted to do. Frank wanted to tell a story with a Ronin continuation. He told me he had that story in mind since the first series ended; the problem was that DC didn’t want Ronin, DC wanted Dark Knight. And I come to DC Comics, and DC still just wants Dark Knight, you know? And that’s just the reality of it. Ronin was very successful as a creative vision, and it continues to sell 40 years later as trade paperback, but it got overshadowed completely by Dark Knight Returns, clearly.

So when had he first broached that with you at DC?

We talked about it over time, but, you know, I could speak honestly: the reality is when you share ownership of a property with talent, and you’re paying talent a very high fee to create product, you want to make sure you receive as much of the profit yourself as a company. So for DC, the greater return was always going to be a Dark Knight property rather than a Ronin property, you know? And Frank never took the point of saying, “You’ll never get that unless I get Ronin 2” - he was very magnanimous about that.

So the good part is, that allowed us to be able to do that property as the first thing for Frank Miller Presents, which I think was appropriate, you know. There are certain things that Frank won’t repeat himself on, but will continue with. That’s what we’ll wind up seeing more when he moves over to Sin City, which is something that’s much more personal for him. Blood & Dust is a different book. It’s not Sin City, it’s another direction, so therefore it’s not a repetition. But the reality is it’s an all-original idea.

I mean, that’s a blessing and a curse, though, isn’t it? Because on the one hand, you obviously want to see—and the market probably needs to see—new ideas and creators pushing themselves. At the same time, you know as well as anybody that when Frank did Dark Knight 2, the general reaction was that everyone wished it was Dark Knight 1.

Exactly. Yeah. The truth is, it’s the greatest challenge we all have. I used to say this at DC all the time: the hardest thing you could do in comics today is the same thing, because nothing ever goes out of print. You get the creators in the ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘70s, into the ‘80s before trade paperbacks really took hold, and the only place people could see the old stuff was in the back issue bin, and they had to go hunting for it. Now if it’s a great book, it’s going to be on the shelf: it’s going to be in print for all time. And because of that, you have something you will always be held against. And the problem for all these guys is that work is always going to stay in existence - it will always be judged against them. They’ll always be popular and famous because of their work, but it’s always going to judge them.

I mean, I think of that when I listen to Alan Moore speak about Watchmen. I’m sure that’s got to be very frustrating. You have this one great work that people keep on referring to, and you’re like, “But I’m doing all this other new stuff over here; can’t you just look the other way for five minutes to see what else is going on?” It’s forcing people out of that. And unfortunately right now, you know, we used to say comics used to feed off of pop culture. They used to see what was happening in pop culture, and it became this weird mirror of what was happening when it went and did its own interpretation.

Now comics are pop culture. And even worse, now nostalgia is pop culture. So you can’t even go forward in any way, because what you would be duplicating is yourself, and an old version on top of that. And that’s a recipe for anything repeating old material to fail.

Is there any way you see for the sort of mainstream superhero comics that you’re coming out of to break free of that cycle, or is the only way to do something totally small and independent like this?

With Marvel and DC as corporate as they are right now, I can tell you, it’s just completely-- you know, DC is part of [the] consumer products [division of Warner Bros. Discovery]. And that speaks for itself, you know? My greatest fear at DC was always that we would become a licensee of our own characters, and that’s not far from the truth in some of these cases nowadays. So the truth is, you have to go out there and try, and if you fail, you’ve got to be okay with that. I used to joke at DC all the time that some of our greatest successes are based on some of our greatest failures. So it's not for us to say whether or not [what we’re making is] going to connect. We just have to believe in the craft, and what we're doing: the type of stories we're telling, the strength in [them], and if it finds an audience, that’s great, but if it fails, it won't be because the material isn’t any good, you know?

My source of inspiration now is in some ways The Walking Dead. Starts off as a very small book, but it was consistent, and it got better as it went on and it built an audience. And right now, if you’re spending all your time chasing the dollar of comics—trying to launch big, 50 covers on to—you get that big spike. You’ll be out of business, or that book will be gone, within six issues. Primarily because you spike, it drops, and there’s no way to maintain that level of interest. So you’re either going to do something ridiculous with the story, or you’re just going to end the series and relaunch it - which, again, is a self-defeating prophecy in its own way.

But that’s the thing, right? Because everybody wants to be The Walking Dead or Saga, but at this point it’s hard to name anything beyond those two that are really long-running, successful, independent series that aren’t based on some preexisting property.

You know, I think the key thing you said is “long-running.” Consistency and quality are probably the two most essential things in anything. You’ve sort of got to muscle through all the disappointment, or lack of immediate gratification or immediate success of the property. And again, that’s about a long-term plan. It’s about long-term commitment. And it’s more importantly about a vision you have that is more important than anything else out there. And you’ve got to tune out all the other noises and see straight through to who you are, and succeed and fail based on your own personal vision. If you maintain your vision and fail, there's no failure in that. When you start compromising your vision, and you lose sight of what you’re trying to do, and you’re trying to chase something that’s elusive or nonexistent, then ultimately you do yourself a disservice. And ultimately you’ll fail as the cost of that.

How would you sum up the vision of Frank Miller Presents, then? What is it that you’re trying to accomplish, artistically and editorially?

What we are trying to do right now is put the craft back in comics. To make the story matter, make the art matter again. You know, Frank is very captivated by the success of anime and manga right now, and he believes that’s where a lot of the strength is [in comics]. And we should recognize influences that are not our own, and find a way to build from them, because ultimately the audience knows more than us. And if that’s where the audience is going, we’ve got to figure out what they’re liking about it and build towards that.

And I think that’s why you see a large manga influence inside Ronin. It’s on purpose. It’s not only because of the subject matter, but also because that’s the taste that’s in the zeitgeist right now, you know? All the comic artists and comic creators, they used to be giant sponges of everything that was going on, and soak it all in and then push it back out in this big blur that combines all these styles and sensibilities. And there’s so much great material being created globally right now - we talk about the global influence, but what we’re really talking about is us influencing out, and not influencing back in. And that's something that we really want to bring to what we've got going on here. You know, Frank’s intrigued, not just [by art], but also formatting, and style, and paper stock, and all these other things that make comics interesting in other markets around the world.

Well, and not just other markets around the world, right? Because I wouldn’t be the first to bring up the fact that comic sales in this country keep going up and up, but the share dominated by traditional, direct market superhero comics keeps going down. And it’s manga and YA comics that are flying off shelves. So how do you compete with that? And how do you break into whatever it is that those markets are tapping into?

It’s funny you said that, because organically is how you do it. You don’t try to do the exact same thing. One of the great parts about being at DC was learning from failure. And you know what? The great part about DC was that it was a big enough company that you can fail, so you could constantly try different things to see what might work. But through your failures you learn.

And we did things that tried to emulate manga exactly, and failed with our characters. We tried to bring in other manga material and publish it ourselves, and failed doing that. And what those two failures taught me was that they weren’t authentic. Because by the time we started acquiring the manga material at DC, it was pretty well cherry-picked, and we didn’t have the ones people in other countries enjoyed. Just had something. We thought, “It’s just manga, it’ll work.”

And that’s not how it works. That’s arrogance. And a lot of people approach things just thinking they can put the veneer on it to make it feel authentic and sell to that audience, but you need to break down the type of story they’re looking for: what voices, what the energy is, and pull out what’s attracting people, instead of just thinking it’s a format or a flavor of the month, you know?

But, you know, we look at every concept, and we talk about the different genres. That’s the fun of it. It’s the flavors. For me, I’m doing Ancient Enemies - that’s the closest there will be to a superhero comic in anything we do, and that’s only because I wanted to do a superhero comic. And Frank wanted to do a western, and Frank also wanted to do a young adult book. And that’s why Pandora came about. You know, it wasn’t because, “Oh, young adult books are hot.” It’s like, no, I’m excited by what I see in the young adult market. There’s great shit out there, I want to do that, too. That’s how you approach this, not “Oh no, we’ve got to fill those three empty spots on the shelf,” you know? It’s about finding what’s happening in the market, doing our spin, and having some fun with it.

How are you finding the other creators you’re working with? Are you going out and seeking out names that you already have on your list? Are you accepting unsolicited pitches from people, what’s the process?

Right now, the initial concept is Frank and I are kicking out ideas and we're bringing people in to help us create them. And that's part of the mentorship part that Frank wants to do. He wants to have the initial idea, but not execute it himself - bringing in a new team that’s young, fresh, or different points of view. Because even with Pandora, Emma’s relatively new to the business; the other two writers he brought in, Chris Silvestri and Anthony Maranville, they’re also new to comics - they have successful careers in animation and television, but they want to do comic books.

And we brought them together. Frank sits down with them, and talks them through, and shows them what to do. And you know, when Chris and Anthony turned in their first pass on the dialogue, Frank went back in and rewrote it and said, “These are the voices.” And then he sets the template, and then pushes it out, and sees how much of that lands with the talent when it comes back in. And you’ll see it with each issue that progresses, there’s less and less [of Frank], and more and more learning that’s going on - more and more understanding about what the expectations are of, not just what the book is, but also what a comic should be, and how it should act.

Is there any kind of physical space where these collaborations are happening, or is it all virtual?

Well, I work with a number of Brazilian artists on the Ancient Enemies stuff, so one of their great moments is when they all came up for New York Comic Con. They all came to Frank’s studio, and they got a chance to walk around and talk to Frank, and see what his influences are. And Frank had out his drawing board and was showing them stuff. And even if it’s just an hour or two hours, what they drew from that was impressive. And the same thing - whenever Emma drops pages, she goes to the studio. She wants to talk them through, and that’s fun also, you know? We made an agreement first: any book is about us first. What’s the visual sense? What’s the look of the book? And then who’s the guy to put the words to that visual look? That’s how we build, you know?

Because with books being overwritten as much as they are, and decompressed as much as they are, they don’t give the artist much to do. And you want to keep the artists as excited and enthused as possible in what they’re working on, because the more excited they get, the better the art gets, and the more energy is in that book and page, and the books come to life. I’m working with Danilo Beyruth on Ancient Enemies, and honestly, I just write a full outline. I don’t even do page breakdowns anymore - I’m just running a full outline of what the story is.

Classical Marvel-style.

Yeah, yeah. And we have a blast. He’s such an amazing layout artist and storyteller, one of the best I’ve ever worked with. And I get excited by his layouts: all of a sudden, I see the book, and I’m like, “Oh shit, that’s not who these characters are.” I actually saw a couple of layouts coming up, and I said, “No, that’s not who my characters are.” And I’m like, “But I like these better.” And we meld, and the comic books are a collaboration. Once you lose that collaboration, you lose a large portion of the creative energy that drives it, you know? And you want to make sure you're taking full advantage of all the talent that's working on the book to give it the best chance.

It's interesting to me that you’re still publishing, at least at first, as single issues, periodical issues, in the direct market. What made you decide on that sort of traditional approach?

Well, we started off with the non-traditional approach, honestly. What we wanted to do was oversized books, almost like mini-graphic novels. I was looking to do books [of] 48 to 64 pages - three parts, four parts, six parts at most; nothing more than that in order to build out a book in a series. The problem is the price point gets a little high. And the feedback I got on the first three issues that we put out was extraordinarily helpful and eye-opening at the same time. And that’s why I took, like, two months off in order to reset the line, and meet the expectations.

So what we did was a couple of things. We did a $7.99 price point for a book that was 56 or 64 pages - which, dollar value, is actually better than most comics that are out there right now. But because of the way the art was done–they were always done as double-page spreads on Ronin–I went with saddle stitch instead of square bound. Well, since it wasn’t square bound, the $7.99 price was perceived as being onerous, because it was a comic book, even though the page count was larger.

Because it didn’t have the look of a prestige package.

Absolutely correct. So therefore, I had to either go square bound, or I had to go to a lower price and a smaller page count. So with Ancient Enemies, which was a tougher sell and a new property, I brough the price down to make it accessible for a more casual purchase. For Ronin, I left it at $7.99 because there’s a pre-existing awareness to it, and I felt that was okay.

But for Pandora, another thing came back. They said, this was very good, and had the sense of a of a young adult comic that’s in the marketplace right now, except most young adult comics are $3.99, 32-page books on a monthly basis. And to be honest, we had good expectations for Pandora, meaning we really liked it. And I didn’t want the format to be the reason for people not to find the book. So Pandora, we took the book and we made it a regular 32-page comic at $3.99, and putting it on a monthly basis. Same amount of work, same amount of pages, same actual price value.

But, I mean, it’s a young adult comic. Just to put it bluntly, are young adult readers even going into comic shops?

That’s this great question. Well, okay, this is where the publisher kicks in now. The publisher in me goes, it’s an amortization of the cost of production, with the hope that once we get it together, once we’re done, we will be able to put the book out in a format and style that more matches the young adult reading audience - meaning smaller size, thicker book. But it’s a way to put product out there. And the problem is, we have so little product: I like the idea of putting a couple of things out on some level of frequency, so that we’re on the shelves with more consistency, you know?

You’ve got to remember, we put three books out before Christmas, and then we went away for a month and a half. And it’s almost like now we have to reintroduce everybody back to our line again. But, you know, it’s a slow build. The other thing I’m doing, which is probably counterintuitive to today’s market, is: I’m pulling all the variant covers off the books. I’m only doing one cover on every book. And the reason why is, you find that on new properties there’s no real interest in the variant covers, because it’s not a variant of a character that anybody has great affinity for. So therefore, the only way you’re going to drive attention to the variant is by overspending on an artist, and that’s counter to what the purpose of the book is about.

You mentioned variant covers earlier, and I’m curious what your feeling on them in general is. Because one thing I’ve heard from retailers when I talk to them is that a lot of them are almost panicked about the state of variant covers, and what they mean for the industry. And they’re worried that they’re fueling a sales bubble that can’t possibly sustain itself.

Indeed. And I agree with that. I’ve been hearing that for years, also. And I think they might actually be at the final tipping point now. Because the word I hear is that books are approved with variant covers [in mind] - it’s not even variant covers as an accelerant for sales, it’s now part of the equation for the profitability of a product, which means that’s a really dangerous trap.

So that’s why if I strip our books down to no variants, at least I know what my bottom line is. I know the bottom of my audience, what my true readership is. And it’s a lot easier to plan when you understand what you’re really working for, rather than what you’re sort of pretend-selling for the moment, you know? And all the people that are building on variants, their answer now is to add more covers, which is the complete opposite direction. The ship’s upside-down: you don’t go to the top, because the top’s underwater.

Did you feel like that was a trap that DC was falling into by the end?

Yeah. That’s because [they're] profit-driven on a quarterly basis. You had to hit a number, and that was easy to fix on. You know, you mortgage your future on something for the moment. And you keep on mortgaging it, because ultimately you have to deliver. One of my favorite questions people always ask me is, “Why did you follow up 52 with another weekly series?” And I said, “Because 52 was successful.”

Was that your choice, or was that pressure from the higher-ups?

That’s a number pressure [from higher-ups]. Because the other bad thing about corporate success, it was a double-edged sword. Nobody believed comics were very successful inside the business. So what we did was, we proved it was successful. Then once you prove successful, it’s like a gangster movie. It’s like, “Fuck you, pay me.” Every chance you get: “You made your number. Great. Fuck you, pay me.” And that’s what you’ve got to do. So all of a sudden, you brought the spotlight on yourself. And because of that, you had to keep on paying, so to speak.

It almost disincentivizes successful innovation in that way.

You know, when you’re working to launch a company, there’s a lot of curtains you can hide behind. You can hide behind financial success; you can hide behind IP creation; you can hide behind awards; you can hide behind diversity. But when all the curtains are lifted, you’ve got to basically deliver. And at the end of the day, if you’re not making a number, and they’re looking for places to cut, you’re not supporting your own case. And my job was to protect the company and the people, so the job was to deliver in order that the company was profitable - and therefore was, for the most part, able to operate semi-autonomously from the rest of the company [at its corporate ownership]. That disappeared when we moved to Burbank. But for the most part, that was the plan in place at DC for a very long time, even before I got there.

To return to the question of the comic audience in general, and not just for Frank Miller Presents: is there a concern that the market is just slipping away from readers of any stripe?

I spoke to the Diamond conference, and I said something that a couple of people agreed with, which was that I believe we lost one to two generations of comic fans. What do I mean by that? I mean that whatever we were doing at the moment wasn’t attractive to people looking for something to buy some sort of entertainment. And I think that's when you saw this gravitation to manga. And rather than understand what that audience was going, we doubled down on the audience that we had.

I used to joke–which is not a joke anymore–when I first got to DC about sales on a number of books and price increases. And the simple math was that a book at $2.99 selling 40,000 copies turned the same profit that a book at $7.99 did at 25,000, and a $15 did at 10,000. But the 10,000 book had a hardcover, you had beautiful paper, it didn’t [have to hit a] schedule. Everybody said, “Let’s make more of those.” And I said, “Here’s the problem. I make more of those 10,000, I lose 5,000 people. Like, 40,000 [readers] goes to 35, 25 goes to 20, 10 goes to 5. We’re out of business.”

And the answer becomes, “Well, we just raise the price.” And I said, “Great. We’re going to create a $1,000 comic for 1,000 people. And that’ll be our entire audience at the end of the day.” And I think that’s where we’re heading right now.

And those 1,000 people keep getting older, because every few years they do a survey of the average age of direct market comic shop customers, and it keeps going up.

And we identified that back in the ‘80s.

And it’s still the same people.

And it is. And we keep on doing everything because ultimately–I’m going to get myself in trouble–we’re lazy or scared. It’s either one. Lazy, meaning I’ve got this built-in, easy access to an audience that pretty much buys anything no matter how much they complain. So therefore we can just create for them, and sort of sit back and relax. Scared is: I’m afraid to try anything new because I don’t know what’s out there [in terms of an audience]. Maybe there isn’t anything out there, and if it doesn’t work, we’re done.

So in your wildest dreams, if there had been nothing standing in your way at DC, what was it they should have been doing?

You know, we tried. Honestly, most of the people I’ve upset is because I tried. It’s an interesting thing, because everybody asks for change, but nobody really wants it. That’s the unspoken truth. The second reality is, you have to be able to change your distribution and reach also. I always refer back to ‘70s DC Comics, which is my DC Comics. I adore it, top to bottom. Why? Because it’s so crazy, but it’s also only 40% superhero.

You got westerns. You got romance. You got mystery and horror, and science fiction. All this other stuff moving around, and 40% superheroes. You go to the direct market, 100% superheroes, or 85% superheroes. Why? Because that’s what the direct market wanted. And as the story is told, popular, successful books on the newsstand that were profitable were being canceled to free up resources to create maybe not as profitable, but more focused books for the direct market, which were superhero-based.

And we narrow ourselves, and we’ve created this very tight little box, and it was fed by fandom. Fandom owning stores, and basically only buying what they wanted as the gatekeepers of what [the industry] went to. So we lost a lot of that opportunity. And as the price went up, we lost people a little bit more. But what I did during my time at DC, the first thing we did was the Focus line, which is basically the tagline, “super powers, not superheroes,” meaning people with powers and not knowing what to do with them. Not immediately putting on a cape and cowl and fighting crime or whatever.

I tried to do the pulp line, with the First Wave heroes. You know, tried different things. Even the Young Animal line, and all these other different types of flavors. I mean, my goal for New 52 wasn’t about, you know, unmarried Lois and Clark - although that was a driving force. Or just restarting the books at #1 because we know they’re going to sell better. But it’s to do a vampire [book], and Men of War, and O.M.A.C., and Demon Knights, and all these weird, crazy things under this big umbrella of attractions, with the hope that that umbrella gave them enough life. My two favorite books coming out of New 52 were Animal Man by Jeff Lemire, and then early Scott Snyder Swamp Thing. Brilliant. Brilliant. There were a lot of good things happening on that line that weren’t just about the fact that Superman wasn’t wearing his shorts, you know?

That’s sort of a case in point, though, right? Because every book you just named got rave critical reviews, and fans said they loved it, but ultimately the market goes back to what fans actually buy, which is more Batman.

Exactly. It’s an easy sell. And I tell everybody straight out, we had a rule: one-third Batman. That’s it. Can’t have over 30% of your line associated with Batman. You cannot do it. And the reason why is that you can’t sit on a two-legged stool for very long. You know, I’m old enough to remember that Batman didn’t really break out until the ‘80s. If you look at Batman between the collapse of the Adam West show until Dark Knight, Batman was just an average book - you know, medium-seller. Somewhere around the #40 seller: still popular, don’t get me wrong, but he wasn’t a juggernaut. He wasn’t the X-Men.

He becomes that later on through the skills of the people who execute the product, especially Denny O'Neil just managing that line so smartly. And also that consistency he brought to the books made all the products feel the same, which was important at the time. It felt like you were buying into something the way you bought into the X-Men line. But the reality is that if you over-extend that, and if 50-55% of your line is built on one character, and the next morning everybody wakes up saying, “You know what, I don’t want to read that anymore?” Right. You’re done. You don’t want to be there, you know?

So you’ve got to always be preparing other product in case one of your products just stops working.

It sounds like you’re able to point to a couple of big problems here, which are, number one, the direct market being further and further away from where the mainstream of actual comic buyers are coming from, and number two, the price point keeping it out of reach from young readers. But how do you solve either of those problems?

That’s the hard part, because we’ve looked at other ways. I tried to do the Walmart initiative, you know? I was doing $5, 100-page books, a mix of product in there, old and new, hoping that something would connect with somebody. Truth be told, the resale stores outside of the comic market prefer the higher price point. If I’m going to give up shelf space, I’m not going to give up shelf space for a dollar book or a 99-cent book. I need something that has value, so when I sell it, I make a better profit.

Because shelf space is marketing. You go into Walmart, there’s a profit based on per-shelf, and you have to meet that profit margin by shelf space or else you lose your space. And the only way we can meet that profit margin is by having a price point that’s attractive, yet high enough to generate enough income to make a number. It’s the only solution - this is the way it works.

So then is the only solution the bookstore market, where people appear to be willing to pay that higher price point, because for whatever reason, psychologically, it feels like a complete story in book form?

I think we started our conversation at that point, that the bookstore market was expanding. I think you got your answer right there.