Italy has a strong and rich history in comics, and this is despite (or maybe partly because of) a longstanding cultural stigma: graphic narratives are often deemed an inferior art form and may not be as economically successful as in France, as influential in the collective imagination as in the States, or as ubiquitous as in Japan - but they are here, and have been here a long time. And not without periods of true and genuine excellence. From the first experiments with periodical strips, such as the ones published in Corriere dei Piccoli in the early 1900s, to the roaring success of the so-called “fumetto popolare” (which refers, not rarely with a pinch of judgment, to the production of comics for the masses) by Sergio Bonelli Editore and the sisters Angela and Luciana Giussani, creators of Diabolik; from the “Italian school” of Disney comics to the language contamination and experimentation of masters such as Gianni de Luca, Sergio Toppi, Crepax and many, many others. Those authors, together with the many magazines that animated the cultural scene and gave space for experimentation, marked the beginning of a shift toward a more authorial form for Italian comics that culminated with the progressive affirmation of the graphic novel format. It’s at this point that our story begins. And it begins in the 1990s, more or less.

Sure, the first flags of change existed well prior to the end of the millennium. Some recognize the birth of the graphic novel in Italy as far back as 1967 with the first Corto Maltese story, Una ballata del mare salato ("The Ballad of the Salty Sea", most recently translated to English by IDW Publishing in 2020); despite being first serialized and divided into episodes, the wide-ranging and cohesive tone of the adventure suggests a link with the novel format to the point that it’s not uncommon to think of it as a standalone book to be read from cover to cover. But the list of graphic novel precursors, in some way or form, could go on. From the authorial side of things, we could remember Dino Buzzati’s Poema a fumetti, first published in 1969 (English translation as "Poem Strip" from New York Review Books, 2009); many works of Andrea Pazienza (his Zanardi miraculously in English thanks to Fantagraphics, 2017); and the big guys, Dino Battaglia, Attilio Micheluzzi, Magnus, Vittorio Giardino and Jacovitti, to name just a few. From the publishing side, starting in the second half of the 1900s, we have Oreste Del Buono’s Milano Libri; the first structured experiments of Granata Press; Daniele Brolli’s Phoenix; R&R Editrice; Rasputin! Libri; and, again, all the magazines that created and solidified the bridge that linked a medium perceived as shallow and inconsequential to the better-respected world of literature. All of this was before the actual term “graphic novel” started to become a thing.

But at some point it became a thing. And it’s hard to overstate the importance of Bologna in the mid '90s to this process of growth, change and newly-found cultural legitimacy. I don’t think at any time in Italian comics history was there such a clear geographical protagonist, such a potent melting pot of talent and raw creative endeavour. Of course, those times are long gone, and even Coconino Press (steward of the graphic novel revolution and basically the only publisher to have resisted the flow of time) has moved to other shores. But boy oh boy, if you liked serious comics in those years, Bologna was the place to be: all the publishers were there, most of the authors were there, the soil was boiling with the energy that would, in time, lead to the first comics-specific curriculum at an academy of fine arts in Italy, at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Bologna.

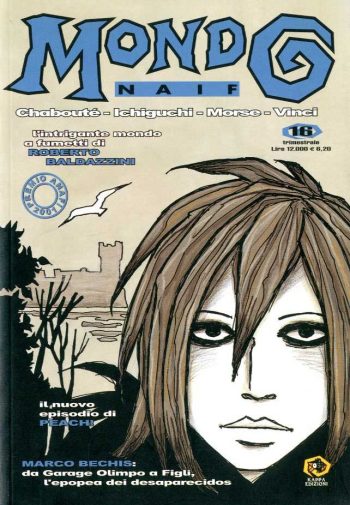

Among the various authors that published their stories in the first wave of Mondo Naif–in my opinion and with no disrespect intended to any others–two shine the brightest, both in terms cultural relevance and temporal persistence: Davide Toffolo, and our protagonist today, Vanna Vinci, one of the most recognized and influential Italian contemporary authors. This is despite her being systematically ahead of time and above par in terms of quality and vision - so, sadly, perhaps not that influential after all.

To be precise, the first part of Vinci's career begins a bit prior to Kappa Edizioni, but let’s not formalize ourselves or get caught in a completist struggle. Let’s focus instead on the most iconic works of Vinci’s Mondo Naif period: they’re a great pathway into/summary of her early aesthetics and poetics, and also a very nice example of traits that would become staples of the Italian graphic novel landscape, from the realistic/autobiographical elements to the intimate psychology of the characters in their everyday life. The three books I have in mind for this purpose are: Aida al confine (Kappa Edizioni, 2003; then BAO Publishing, 2017), which translates to “Aida at the Border”; Sophia (Kappa Edizioni, two volumes, 2005 & 2007; then BAO Publishing, collected, 2015); and Gatti neri, cani bianchi (Kappa Edizioni, two volumes, 2009 & 2010), which translates to “Black Cats, White Dogs”.

They all start with some kind of breakup. The protagonists–Aida, Sophia and Gilla, respectively–are young women about to drop their lives and move to a new place: Trieste, Bologna and Paris (again, respectively). The end (or upcoming end, as it is for Gilla) of a longstanding but quickly-deteriorating relationship is as good a moment as any to move away; probably better than any, since it provides a convenient excuse for your actions (if you’re cynical) or a proper push to do something (if you’re more proactive). These are the first things to highlight about these books. Even if, in their choice of point of view, they almost surely betray some autobiographical root, it’d be reductive to diminish them to mere re-interpretations of their author’s experience of leaving her home in Cagliari to move to il continente, the continent. That's how Sardinians often refer to the Italian mainland, indicating the distance between them and the rest of the world, as well as the length of their journey. That is what it's all about: undertaking this journey to a new place and moving on to the future.

A geographical distance is also symbolic; a journey in turn both physical and metaphysical for the person who undertakes it. I think this would be a nice way to describe the core theme, the heart, of these three books and of their human protagonists. These girls are at a threshold - or, better yet, at a series of thresholds: the one separating adolescence from adulthood; the one separating the family and house you were born in from the ones you’ll make yourself; the one separating the fixity of past identity and relationships, slowly crumbling apart with the possibilities of a future yet to be written. To be blunt and summarize: the threshold which is growing up - not leaving the past behind to forget it, but moving on and building from it.

It’s not by chance that these books are set in cities of rich history and even richer symbology, a great past to “use” as a foundation to build upon, both narratively and metaphorically: Trieste with its dock, its strong winds and its border-like soul; Bologna, “the red city”, with its archways that shelter from rain and sun (but not from the heat, trust me); briefly, Rome, and more intensively, Paris, whose defining characteristics are harder to pin down but also better known, so I will spare myself the struggle of attempting efficiency.

Even though the use of real, well-defined places has kind of shifted out from the Italian graphic novel “canon”–with many authors now preferring more abstract (but still recognizable) scenarios–this trend had been a huge deal in the past, especially in the era of Mondo Naif, when comics set in Bologna, for instance, were nearly uncountable. Rarely, though, has it been as impactful and meaningful as in Vinci’s work - a detail too often overlooked, but an important one! These cities are not just a landscape, a setting for the characters to perform their coming-of-age stories; the cities are characters themselves, grounding the reality of the narrative in a precise point in space and time, and creating a feeling that this story couldn’t have happened anywhere else in the world. And it happens, at the same time, without making the story lose generality or relatability (a hard balance to maintain). This creates a strange feeling of intimacy: not “this person could be you” because you recognize the places, nor “this is a generic person in a generic place” so that you can identify yourself with the protagonist, whoever and wherever you are; but “you could meet this person, this is a person you could actually happen to know”.

Aida, Sophia and Gilla are people that could exist, in places you could visit, living the ordinary troubles of leaving adolescence and facing dilemmas everybody faces. None of this would have ever worked out were their stories set in a fictional generic place such as the “province” (a typical Italian anthropological, sociocultural and therefore narrative trope that roughly translates to the suburbs, but without suburban poshness). And, on top of that, none of this would have ever worked out if Vinci was not able to keep both her feet on the ground of reality–especially when it comes to character psychology and behavior–and her head in the skies of supernatural symbolic elements. So, here enter the ghosts.

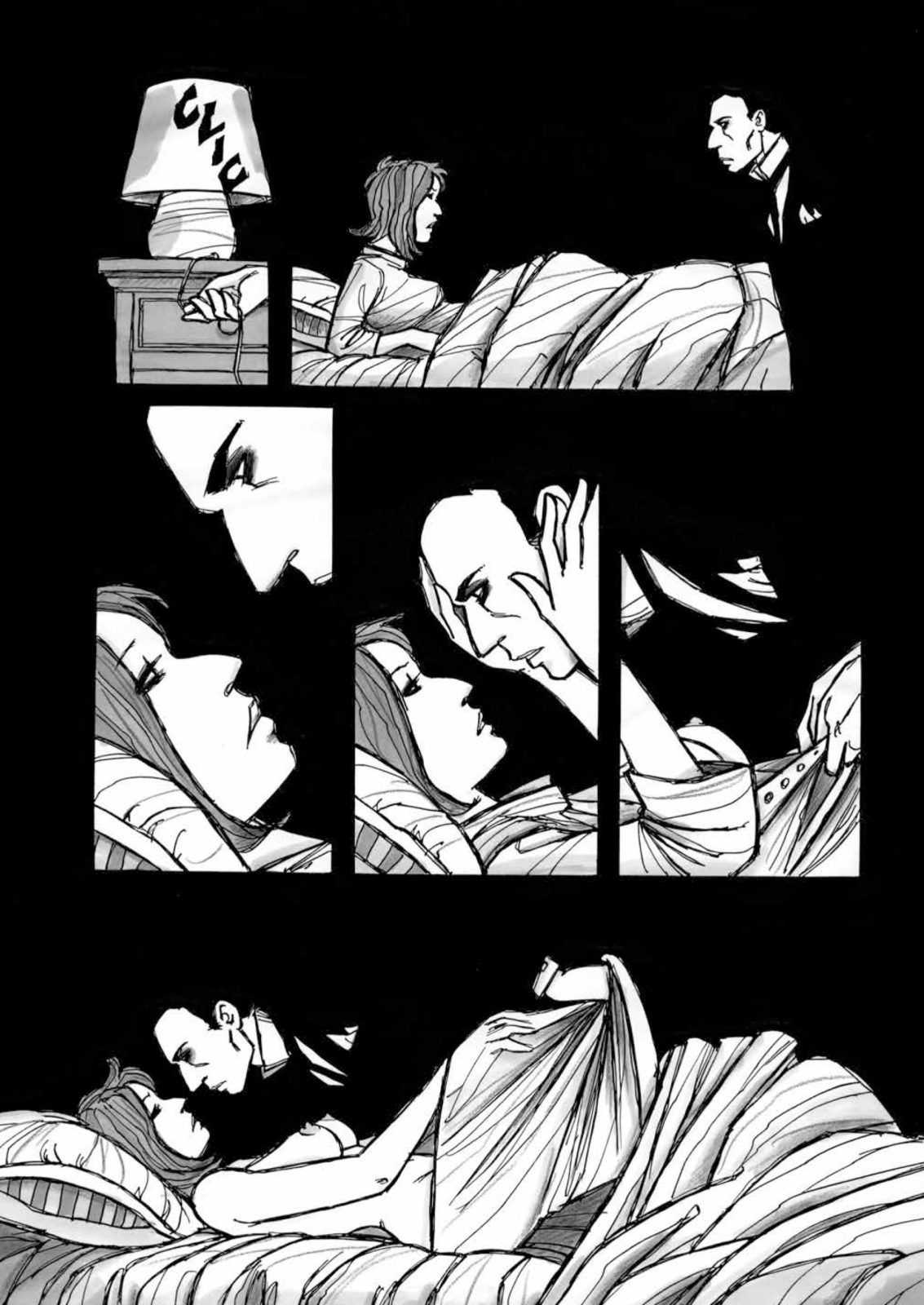

Vanna Vinci’s work has always been full of vampires, ghosts, even real historical figures whose relationship with death are made somewhat mythical. Sophia, for instance, is obsessed with alchemy in her eponymous book; she’ll end up meeting an immortal singer, bored to (non-)death by her own voice, and then Nicolas Flamel, the legendary alchemist himself. But the journey of Aida and Gilla is maybe more straightforward in this sense. The former will meet in Trieste a fascinating young man, and will have with him a sort of sentimental relation, only to discover he’s a relative of hers who died many years prior during the War. The latter will rejoin in Paris with Roberto, a boy she loved that died in an accident just before the two of them could express their feelings.

And these bonds with the dead, this piece of the journey the protagonists share with them, is always a meaningful one. The dead appear to be better people than the actual, self-centered, uncaring and insensitive boyfriends these girls are trying to move on from. In the case of Gilla, the direct comparison between the newly-found ghost of Roberto and her shitty relationship with her alive-and-well odious boyfriend is almost comically merciless. But this is not to say that the “message” of Gatti neri, cani bianchi, or of the Vinci’s other books, is to dwell in painful memories or to get lost in regrets and what-ifs - that the present will never be as good as what could have been if death didn’t pull us apart. It seems to me that everything goes back to the symbolic value of the past as something that lives with you, and that helps with (or at least contributes to) building your future. The intertwining of death and love is not only a great archetypical oxymoron, but also one that very strongly relates to adolescence: that period of life where one becomes aware of their own mortality (but often doesn’t care); that period of life where one starts to have a past, but still projects themself into the future. If adolescence is then a threshold, the ghosts and the vampires and the immortal beings these girls meet are proper liminal denziens: dead and yet here, with their feet divided between night and day; relics of a past that is lingering, and therefore is also the present and the future.

I feel this sums up what strikes me about Vanna Vinci’s earlier works, and I hope it gives at least a small perspective, an entry point, on her poetics. If so, we’re ready to move on the next stage, one completely different and yet not so distant, since it retains many of Vinci’s already mentioned or hinted characteristics: her borderline obsessiveness in recreating true places and historical events; her uncanny ability to make her characters alive (even the dead ones); her everlasting interest in the dance of love and death and in the symbolic value it generates. Before we move on, though, a brief detour.

Anyway. This is not to say that comic biographies didn’t exist back then: you had your occasional hits such as Kiki de Montparnasse (Catel Muller & José-Louis Bocquet, 2007) or, later, Chloé Cruchaudet's Mauvais Genre (2013); it's just that the genre wasn’t as ubiquitous as it is now, and production was more often than not driven by the genuine interest of authors, as opposed to the promise of quick sales following death anniversaries. This is particularly true for the Italian market, which has seen a recent rise in popularity of poorly-made biographies, and even a small wave of publishers explicitly dedicated to these kinds of books. There are, of course, exceptions in this trend, both in terms of quality and in timing: extraordinary examples include Marco Corona, Paolo Bacilieri, and–getting to the point–Vanna Vinci.

After the Mondo Naif books, and the later graphic novels that we can still associate with that vibe, Vinci turned to the biographic genre, showing once again “how it’s done”, albeit in a new field. This segment of her career risks of being underestimated–I know I have underestimated it –especially by a public bored to death by an overgrown production of insipid and soulless books that read like “Wikipedia Illustrated” or “Art History for Dummies”. And, to be fair, Vinci’s biographies may seem like that at the first glance of a prejudicial eye, especially given their text-heaviness. But there’s (almost) nothing further from the truth.

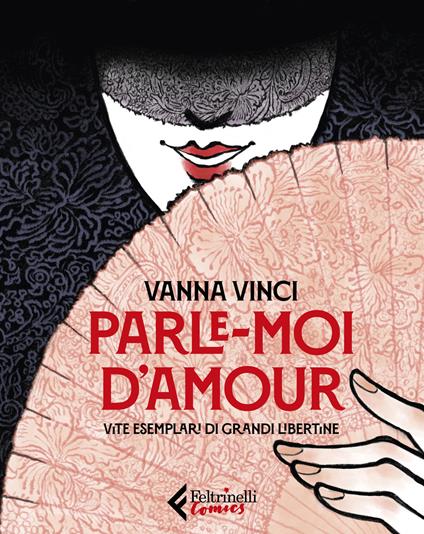

Let’s start with her choice of characters: Luisa Casati, aka Marchesa Casati, a noblewoman who lived between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century and is famous for her magnetic and eccentric lifestyle, who accumulated and dilapidated multiple fortunes and died in poverty in 1957 (La Casati. La musa egoista, Rizzoli, 2013; available in English as "Casati: The Selfish Muse"); Tamara Łempicka, Polish painter and icon of Art Déco, with a stunning history of personal and sexual emancipation in the early 1900s (Tamara de Lempicka. Icona dell'art déco, 24 ORE Cultura, 2015); or Maria Callas, naturalized Italian opera singer of Greek origins who became an icon through artistic and mediatic success (she was known as the “divine Maria Callas”), who died at 53 of heart failure, which many believed to be linked with congenic health issues and the significant weight loss she endured before becoming famous (Io sono Maria Callas, Feltrinelli Comics, 2018). To top it off, Vanna Vinci’s most recent book is titled Parle-moi d'amour (Feltrinelli Comics, 2020), with a subtitle that roughly translates to “exemplar lives of great libertine women” - it’s a collection of shorter biographies of licentious women of different social extraction, motives, historical period and notoriety.

From this brief list one could see value, probably even a political one, in the choice of protagonists. They have been–and in a sense still are, since their lives made them immortal (here we go again with death being more of a threshold than an end)–important and iconic women, relevant figures of their time, with life choices that are often deemed controversial to the present. And their lives are recounted with nothing but respect, if maybe a pinch of admiration that never becomes envy. In a recent chat I had with Vanna we were exploring her career in order to prepare for a panel at a festival, and she said (I’m paraphrasing, hoping to do a decent job): “I’m not those women and possibly I’d never be able (nor maybe I’d want) to live their lives. In a sense I know them because I can study what they’ve done, but from there it’s a matter of respect: I couldn’t judge them in any way even if I didn’t share their experiences and choices.”

From this brief list one could see value, probably even a political one, in the choice of protagonists. They have been–and in a sense still are, since their lives made them immortal (here we go again with death being more of a threshold than an end)–important and iconic women, relevant figures of their time, with life choices that are often deemed controversial to the present. And their lives are recounted with nothing but respect, if maybe a pinch of admiration that never becomes envy. In a recent chat I had with Vanna we were exploring her career in order to prepare for a panel at a festival, and she said (I’m paraphrasing, hoping to do a decent job): “I’m not those women and possibly I’d never be able (nor maybe I’d want) to live their lives. In a sense I know them because I can study what they’ve done, but from there it’s a matter of respect: I couldn’t judge them in any way even if I didn’t share their experiences and choices.”

I think study and respect are the key words here, and I’m firmly convinced that they are the two words separating Vinci’s biographies from so many others. There’s a palpable level of obsession, of research, of slow and methodical scrutiny that transpires from the pages and that makes these books accurate and dense. This is not to say that there’s not a selection of facts or an adhesive-to-reality approach that erases narrative invention. Of course there is. But from the huge historical background, and from a deep knowledge of it–the kind of knowledge that takes time to build–Vinci distils the important and foundational elements that give the reader both an historically accurate reconstruction of a life and the key to grasp its very soul. Which is a difficult thing to do and it’s again a matter of respect: of giving life back to these women, being fully aware of the dichotomous nature of their being. They are both people that really existed, and therefore are not to be judged, and also characters that are created by the author though her selection of facts and choice of words.

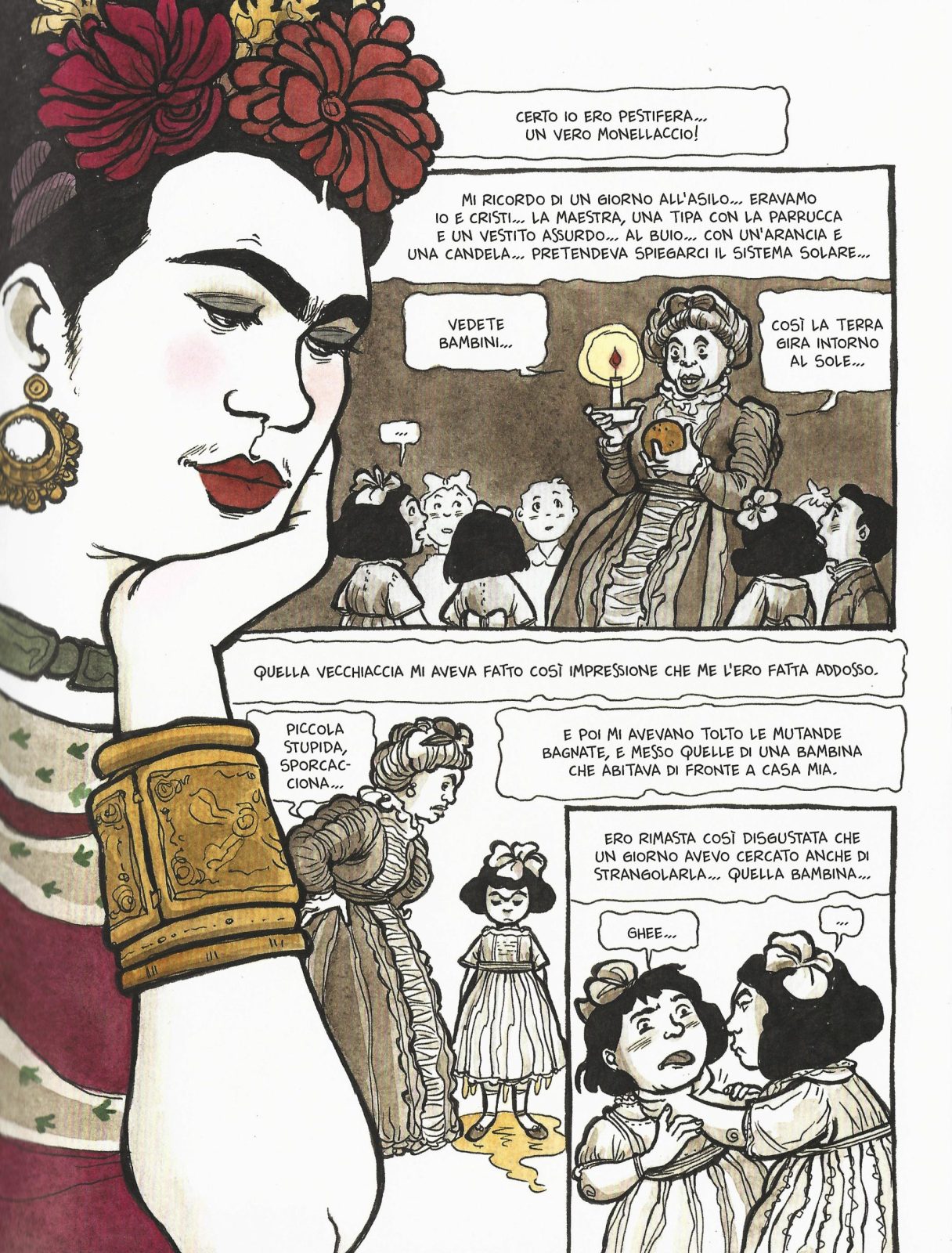

All of this–the respect for the character and the person it represents, the ability to convey the character's essence without being pedantic nor superficial, the masterful recreation of the complexity of life (especially of the lives of unconventional people)–is most apparent in Vanna Vinci's most convincing biography, which I've saved for last: Frida Kahlo. Operetta amorale a fumetti (24 ORE Cultura, 2016), the subtitle of which roughly translates into “Amoral Comic Book Operetta” (an official English translation, released by Prestel Publishing in 2017, changes the title to "Frida Kahlo: The Story of Her Life"). I am concluding with this book because it’s not only my favorite, but possibly the best way to circle back to what we were saying earlier about death and love and liminal creatures and so on.

Frida Kahlo is a very important artist and an icon of popular culture, ça va sans dire. She’s therefore the subject of countless pop biographical endeavors, few very good, many ranging from bad to worse; the charm of her art, and of a life of huge symbolic and political meaning, is second only to the strength of its commercial potential. Frida Kahlo is also–maybe precisely because she is so well-known, at least at a surface level–a very difficult person to write a biography of without falling in one of two traps: becoming judgmental, leaning toward a narrative that fits what the author wants to convey due to a personal agenda or mere shallowness; or oversimplification, cutting out the problematic bits and focusing only on some cherry-picked aspects, which of course doesn’t render the complexity of the character. Frida Kahlo is multifaceted, and not without contradictions in the intricacy of her relationships: with her art and with herself, with Diego Rivera, with her culture, with sexuality, with her lovers, with pain and death… it’s so easy to miss or omit some of that.

She is also a difficult subject for a biography because her life and her art are so deeply entangled that you cannot speak of one without talking about the other, which is kind of tricky if you’re doing a visual biography; the result is a continuous mirror game that risks self-exhaustion. To this day, just two good comic book biographies of Frida Kahlo come to mind: the one by Vanna Vinci, and Krazy Kahlo by Marco Corona, about which we’ll hopefully talk in the future.

Vinci capitalizes on her experience as a comic book artist to tackle all these complexities in a somewhat unconventional, properly fictitious way. The book starts as you’d expect from a book of hers: a fluid flowing of panels that dissolves and reassembles in bold compositions; soft and expressive lines that are reminiscent of the influence manga had on the author, combined with a mastery in the use of color rarely present in her early works. Visually, this allows Vanna to both render the more narrative bits together with her reconstruction of Kahlo’s paintings and their recognizable traits, retaining internal cohesiveness. But from a narrative point of view, the text is what drives the story forward. There’s a lot of text, a lot of it in captions.

The captions flow as a dialogue between Frida and an unseen interlocutor: they chat about Kahlo’s life as if remembering and commenting on it, pitched somewhere between an informed interview and a friendly chat. It’s not far into the book that we discover the identity of the interlocutor, in something that I cannot describe as anything but a plot twist: it’s Death itself, longtime companion of Frida’s life. This revelation, in a way, changes the perspective and the approach of the reader because it connotates what’s going on at different levels: on a storytelling level, because it provides the structure and the narrative excuse to line up the events of Kahlo’s life; on a symbolical level, since it gives those events meaning and links them to the continuous presence of Death; and on an aesthetic level, by giving context to the art that those events originated.

The introduction of Frida’s interlocutor and the friendly chat with an entity we usually are not friends with also immerses the book in a strange, somewhat familiar but uncomfortable mood, as if the reader is eavesdropping on a private conversation of two longtime companions. This alone tells a lot more about Frida Kahlo’s life than any simple recollection of circumstances; there’s intimacy in this conversation, the kind of intimacy that springs only from an acquaintance you don’t resign to accept, but instead fully embrace. It’s an intimacy that facilitates an unusual feeling of honesty and thoroughness. And from that honesty and thoroughness, page after page, the portrait of a complex artist emerges together with a commentary upon her. If ever a comic book could be successful in actually being an emotional, generatively intricate and meaningful (in all possible interpretation of the term) biography, this must be one of the most fulgid examples of it.

There is a lot more to say about Vanna Vinci’s work; we have barely scratched the surface of her oeuvre, avoiding her humorous strips, as well as her occasional travels in Bonelli genre comics, focusing instead on a few representative books from her two major currents of work. We could go on, but I feel this is enough of a good start to stop. Let me finish by saying this. In almost 30 years of an artistic career and almost 30 books (if I counted right), Vanna Vinci has proven herself again and again one of the most relevant comic book artists of recent Italian history. Now, after piloting one of the most prolific eras in the Italian cultural scenario, and after showing us what a good biography in comic form looks like, she told me in the same chat I mentioned earlier that she may move on from biography towards (or back to) fiction. Which is kind of a full circle, a moving forward that takes into account what came before. After all, as ghosts having relationships with adolescent girls may symbolize, future and past are not so disjointed after all. I can’t wait.