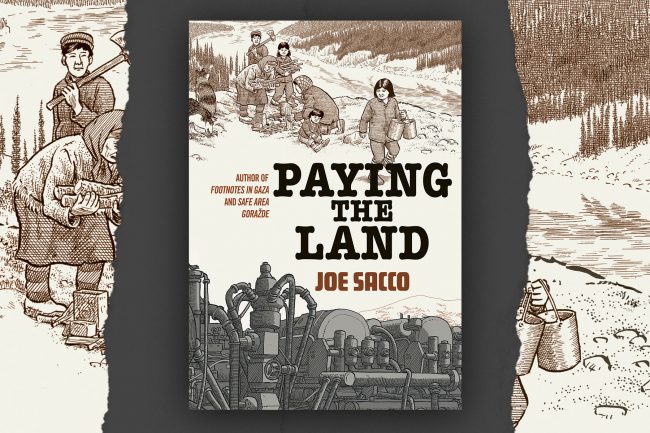

Joe Sacco has long been one of the most important cartoonists in the world. His books like Palestine, Safe Area Goražde, and Footnotes in Gaza have changed comics, with nearly every creator of journalistic and nonfiction comics that I know citing him as an inspiration and a guiding light. He has demonstrated what the medium could accomplish and if anything, his ambition has continued to grow over time.

In his new book Paying the Land, Sacco traveled to Canada’s Northwest Territories. While his original plan was to investigate resource extraction and the effects of global warming, once he was there, his plans changed. In all his work, context is key, and just as he wants to go deeper about places and events that people often know only as headlines or newspaper articles, Sacco is always aware of history. In Canada, Sacco investigated the effects of colonialism and genocide, residential schools and land claims. He considers how Canada has been more open about the past than the United States, but that hasn’t translated into changing present behavior, and about a generation of youth that is trying to find a new way forward. It is some of his best work and we spoke recently about structure, history, and the Rolling Stones.

I wanted to write something about climate change. I wanted also to get away from writing directly about violence. I started thinking about indigenous people and how the resources that contribute to climate change are generally extracted in those areas where indigenous people live. Places on the peripheries. A few years before, Shauna Morgan contacted me from Yellowknife. She’s in the comic and wanted me to come out there and give a talk, but I couldn’t get up there. She mentioned, if you do get up here, there’s a lot going on with indigenous people that’s worth a look and I’d be happy to show you around. So I had that in the back of my head. I contacted her to see if she was still around. I contacted the French magazine XXI, are you familiar with them?

I’ve heard of it, but never read it.

It’s a pretty great publication. What they do, among other things, is send cartoonists out to do thirty page stories. I contacted them and they agreed on a two part series about my trip up there. I went up in March 2015. I hooked up with Shauna and we did a trip up the Mackenzie River Valley. I started working on this piece for XXI and it became clear that there was a lot more going on than a sixty page story would allow for. I decided to turn that sixty pages into a book and I went back to find out more. Originally I was thinking I’d do a comparative study – one story in Canada, one story in South America, maybe something in India – about resource extraction and indigenous people, but this book project took over a fair amount of my life for four years. I’m not sure how comparative I’m going to get.

What was in those sixty pages? Was that roughly the framework of this book?

What was in those sixty pages? Was that roughly the framework of this book?

It was. I basically used those pages as a nucleus, but I wasn’t satisfied. I didn’t think I’d gotten to the essence of things. I’d touched on a lot of things – for example, residential schools – but I wasn’t satisfied that I was getting a full unadulterated look at that particular issue. That was one of the reasons I made the second trip up. The first one just didn’t cut it. I also was approaching things too meekly the first trip. I was being told, be very careful when speaking to elders, let them talk, don’t push certain questions. Someone told me the whole residential issue was very sensitive. Of course it is. But on the second trip I was a little more forward about what I was looking for. I was mindful of what people told me, but I was more myself, let’s say. Just letting my instincts take over. I didn’t have to push to hear stories about alcoholism. Those stories came out. The residential school stories came out, too. It was just a question of focusing people on those things. You have to let people know that’s what you’re interested in hearing and guide them through it. Just in general when people are answering questions they tend to skip around. You know this – you’re probably getting it from me. You have to keep people on track, or at least know what you’re looking for.

I kept thinking about how much of your work is about context.

It has to be.

You make it clear that it’s not about isolated events. You can’t look at resource extraction and how these communities function without taking a broader more historical view.

Absolutely. I went up there with a specific question: how are indigenous people dealing with resource extraction? But the bigger story which began to confront me is that this is a story about colonialism and all the implications of that. If you’re talking about colonialism you have to get into the historical context, the attributes of colonialism that manifest in people’s lives. That leads you to residential schools. Just as it leads you to the land claims issues. The story, not just in the Northwest Territory, of indigenous people trying to claw back something from the governments that have taken away their land. It was a bigger story than I had originally expected. That always happens to me, though. I read a lot about a certain subject. I had read about land claims and pipelines, but then you get there and realize that residential schools are the elephant in the room. Residential schools obviously damaged the culture. The residential schools were meant to damage the culture. I don’t want to mince words – they were meant to destroy the culture. Everything is very related. People who came out of the residential schools told me they were very damaged by them, and they had to reconfigure themselves. At the same time they had to deal with the government over land claims issues and with their own people. There was a lot swirling around. Resource extraction was just a cog in this bigger machine.

And central to this colonial idea is the relationship between genocidal behavior towards people and this exploitation of the land.

Exactly. The people didn’t matter much to the government of Canada – or the Dominion of Canada – because it wasn’t a place suitable for settler farming. If you look at what happened in North America – and many other places – what the colonists wanted was land to farm. You can take what John Locke said about how you mix the sweat of your brow with land and that’s property. That’s how they thought of every place they went. This is my property. They didn’t see the indigenous people as “working” the land, even though they were hunting and trapping and fishing and living there. The Northwest Territory wasn’t agricultural land so they didn’t care much about what indigenous people were doing up there – until they found oil and gold. Then it all changes. The Western European structure is based on legalities and making sure you dotted your I’s and crossed your T’s, so you need treaties. You basically have people sign over their land, which they never thought they owned in the first place.

I was reminded of Jeet Herr’s piece a few years ago about the boringness of Canada and how on the one hand it was a way of saying that they weren’t British or American, it was also a whitewashing of the nation and its history.

I was reminded of Jeet Herr’s piece a few years ago about the boringness of Canada and how on the one hand it was a way of saying that they weren’t British or American, it was also a whitewashing of the nation and its history.

That’s absolutely true. There’s an acknowledgment in Canada that this was cultural genocide. There was violence when settlers first came there, but in the last 150 years there were not cavalry charges like we had here in the United States, but the effects were to do the same thing. Subsume a people and get rid of them in some way. Get rid of their culture at least, so even if they’re still there, they’re assimilated. I tended to think of Canada as the North Americans who got it “right.” But they really haven’t. Or they didn’t. I will grant them this – there’s been much more reckoning, for what it’s worth. I don’t think it goes far enough at all, but there’s much more awareness of what happened to indigenous people. There’s some acknowledgment – although a lot of that is just words. It’s a lot more than we’ve ever gone through in the United States, where we’ve never really delved into what indigenous people suffered here officially. At least in Canada they’ve made some effort. I’ll grant them that.

As far as the book, I’m curious about the years you spent working on it and how much was finding a structure that worked for you.

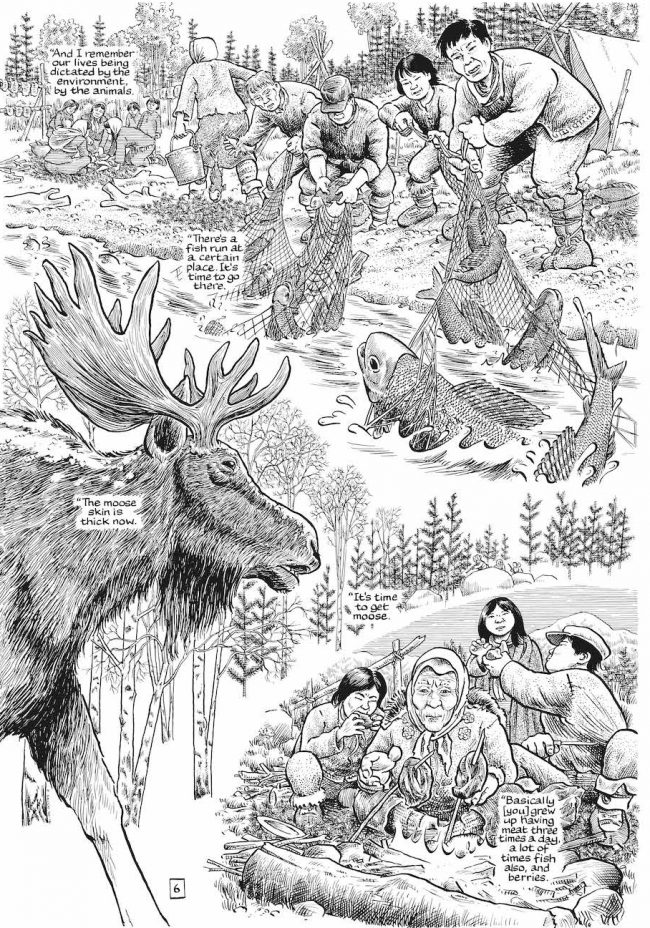

That’s a hard thing to describe, Alex. Every book has its own logic somehow. I transcribe all my tapes so I try to relive the trip by hearing people’s voices again and hearing the emphasis in their voices, the pauses. That swirls around in my head and at some point I have an epiphany. There are things that are obvious. If you’ve completed a college research paper, there are things you know how to do. There’s residential schools, land claims, the historical element, the cultural element. You see those things and sometimes they fit together relatively well. In this particular case it became clear to me from rehearing the tapes I recorded of Paul Andrew talking about growing up in the bush. I was really lucky to have that conversation because I’d heard many things from many different people, but in bits. He just laid it all out without me having to interject many questions. And it was such a beautiful story. I thought, this is the way to start. This tells you what life used to be like and the reader will be able to see what followed within that context. It makes you understand why people are fighting to get their culture back. When you see the relationship of the Dene people to the land you begin to understand why everything is about the land. Everything the Canadian government did to them was also about the land – not just taking it away by treaty, but trying to sever the relationship that people had to the land. Which they did through residential schools, and schooling in general. It all follows.

What was especially interesting about Paul Andrew’s memories and opening with that was how recent it was.

Very recent! I’m almost sixty and people my age North of Yellowknife had some recollection of growing up in the bush. It was very recent. The last people came out of the bush, it seems, in the early seventies. Mostly they were coming out in the fifties and sixties.

It’s within human memory, which isn’t always the case for much of the U.S. But I said before about how context is always important for you, and after opening with Paul’s story, you back up and start with you in Yellowknife and giving us a sense of just how remote this area is.

A lot of that was how the XXI piece was laid out. I’m sort of introducing myself to the Northwest Territories and I’m also introducing the readers in the same way. I’m going out very focused on fracking and what’s going on – much like I was in reality. Then slowly the story behind to expand. The expansion of the story in my own mind is reflected in the structure of the book.

How much of that first trip in 2015 was covered in the book and how much happened in the later trip?

Most of the stories about fracking happened in the first trip. I did two trips to Trout Lake. The first trip dealt with fracking and then there were ideas I got from the first trip that I explored in depth in the second. For example, there’s mention of residential schools in the XXI piece but nothing that congealed. I had to go and redo that. That was the main thing I wanted. I wanted to get the residential schools and the land claims. I wanted to interview people involved in land claims. I wanted to talk to younger people. I wanted to find out what resistance looks like now.

It’s in the last chapter you talk with younger people who are in their lives trying to synthesize and deal with everything you raise in the book.

It’s in the last chapter you talk with younger people who are in their lives trying to synthesize and deal with everything you raise in the book.

The first trip I came back with a lot of questions marks. I was able to cobble together a 60 page story, but I felt like I hadn’t done my job. Let’s just say that. That’s why I decided to do a book. There were too many questions in my own head – and I knew that the story could have been better. The first trip was so unfamiliar to me that just understanding very basic things took up the full three weeks. I knew what to ask and how to go about things in the second trip.

Getting into land claims and how that’s played out over time – and continues to – there’s a lot there to lay out for readers.

To me it’s vital. It’s also a question of what can a comic book do? How far can you push the reader into a very complicated issue. I’m always reading books that are very complex. Just as we all do. As a reader when you’re reading prose you expect a lot from yourself, I think. They have a lot of moving parts. In comics the advantage I think is that you have all these moving parts and illustrations can cement things in a readers head better. I tried to push things as far as complexity goes. Land claims are complex. You have the government of Canada, the government of the Northwest Territories, and then you have the different Dene groups each with its own agenda. You have the complexities within communities, the strains within communities over claims. The tension between communities. It’s all very complex. You’ll have to tell me if I pulled it off. It depends on the readers patience. I guess I’m expecting readers to be patient.

Having maps the way you do, certainly helps to show some of the complexity.

Yes, and I felt I had to tell the story. You need the complexity to understand what’s going on. It’s not a question of indigenous people want their land back and are in negotiations. You have to know how it works, how people are divided, the tensions that arise in communities over it, and why.

How the government of Canada doesn’t do anything and so the Dene have to negotiate with the Northwest Territories, the Yukon, and British Columbia – not all of whom will sit down to negotiate, so everyone is carving up parts of parts. It is complex.

You realize how difficult it is for indigenous people who never thought in terms of those provincial or state borders. Thats not how they think or live their lives and now they have to deal with these Euro-Western constructs and boundaries. Now they’re dealing with the three different entities that have three different ideas. You begin to understand how difficult it is for people there. I want the reader to see what indigenous people are facing.

We were talking earlier about Canada has acknowledged the past but it shows how that mindset of how they treat the First Nations and the land is not in the past.

No, and it won’t be. Canada is built on a lot of resources. That’s where the money is. Once you’re talking about money, you’re talking about power. Why would British Columbia going to give up oil to this small community that used to live there? There’s a good case for it, I think, but there’s a lot of money there, too.

One person you spoke with said, this our land, these are our resources, and we are willing to share it with you. But the government is not offering any control or a significant amount of money.

Right. They’re constantly being pushed through Euro-Western filters. They have to think about land in ways that is not how they traditionally thought of land. All these different rights and procedures. They’re forced into negotiating in a Euro-Western framework because the government in Canada believe they hold all the cards.

It was a revelation for me to be there. It changed a lot about how I think of property. It made me read John Locke and people who write about property and the Western version of property. It’s one thing to hear people say, we don’t own the land, the land owns us. But when you’re with the people, you begin to realize how profound that is and what it means to them. It made me question the whole Western notion of land ownership. It made me think about it in a different way. It goes way beyond, we’re destroying the land.

You’ve talked about structure as something you don’t think about a lot and in other interviews you’ve talked about designing the page in a similar way.

You’ve talked about structure as something you don’t think about a lot and in other interviews you’ve talked about designing the page in a similar way.

I don’t like to plan those things too far out. I need a certain amount of creativity on a day to day level. Generally the script is pretty hammered out before I start drawing. I might edit as I go along. I want some spontaneity on a day to day basis, so I don’t storyboard. Every day I look at the page and say, what am I going to draw now? I have the script, I have these captions, what goes with it? That’s how I approach it.

This person is telling you a story so it’s about balancing showing what they’re saying, showing you talking with them, other elements.

And to make those decisions three or four years in advance, I’d feel like I was just connecting the dots. Creatively that’s very difficult to do. It would make me feel dead. I know a lot of cartoonists don’t see it my way. They like to storyboard. Everyone has their own way. It’s also partially a shortcut. It seems tedious to me to storyboard things.

Drawing more than you have to.

Or thinking about it more than I have to. Sometimes you can think about three or four panels in front of you. If you’re storyboarding, you might be trying to think of fifty in a day. That might be too much for your creative brain to deal with.

I suppose dealing with long projects, your books take a few years each, to try and make each step creative and essential is important.

Every book streamlined the process somewhat. Sometimes that meant doing more work. You’ve read Palestine? That was nine comic books before it was collected. So I would write one and then draw one, write one and then draw one. I had an overarching idea of where I wanted to go with it, but it was more work because it wasn’t as structured as some of my later projects. By the time I was doing the Bosnia work I was taking all my journal entries, all my interviews, and indexing them by person, by subject, so that everything would be at my fingertips. I generally come away from these trips with hundreds of pages of journal entries and I realized that it’s really time consuming to flip through journals looking for something someone said. It can take weeks to organize my notes so that anytime I think of a subject, it’s at my fingertips. It’s something I learned over time. There are time saving things that I use that take a long time to get going. Indexing takes a lot of time, but it saves me tens times that amount of time later on.

You adapted to making books quite well.

A lot of my books were in depth projects that needed that.

Safe Area Goražde was the first project you made intended as a book, and it remains a pretty brilliant book.

Thank you.

As far as going North, you mentioned that Shauna helped set things up. How easy to find people willing to talk? And how important is it to have someone local to help set that up?

Shauna was vital. I’ve learned that anytime you go into a community you don’t know to do journalism it’s best – or I’ve found its best – to have someone to introduce you. If that person is trusted within the community, that trust passes over to you on some level. What was difficult was that the first interviews I did were with people who are more traditional than in other places. It wasn’t difficult to talk to people, but the structure of the interviews was quite different. That’s where I was told to just let people talk. A number of times when I talked to people, they didn’t want me to record or take notes. So it was an hour, hour and a half of people telling me often very interesting stuff, going to where I was staying and writing it all up, and then going back to them and checking things with them. Those interviews were interesting but I couldn’t use a lot of them unfortunately. That’s also what frustrated me enough to go back again and behave differently and convey that it was important to get their words. It became a balance of how they do things there and getting what I needed.

Sometimes it wasn’t a problem. Like with Paul Andrew, that interview was on the second trip and we just sat down and I said I wanted to talk about residential schools, but then he started telling me about life in the bush and it was just the most eloquent thing. I didn’t have to prod him at all. I prompted him about the plane, which shifted into his story about residential schools. People are wary up there. You think you’re the first one to ask these questions and you realize you’re not. A lot of people have gone up to do research. The thing that got pushed back at me is, people come here and take my knowledge and I get no benefit from it. We don’t see those people again. We never hear anything from them again. I had to be aware of that. Sometimes people don’t want to talk to you for that reason. Other times they give you the benefit of the doubt. Stephen Kakfwi, the ex-premier, turned out to be a great interview but when I first met him, he was pushing back at me asking, why have you been trying so hard to get ahold of me? He was really irritated. I just apologized to him and he said, okay, let’s just talk. And we did and he was absolutely open. I’m constantly learning more about talking to people. I’m constantly finding out things I didn’t know about communication. Maybe from the outside it looks like I know what I’m doing – and I’ve learned a lot – but I’m always surprised by how much I need to know. Especially in communities I’m not used to. When I talked to really traditional people in the Northwest Territories, I had to learn to make it clear to them how I was going to use the information. If I went to Gaza to talk to people, people go, oh, another Western journalist is here. It was much more complex than I thought it would be. Which was one reason I went.You always have to approach these stories with a bit of humility, because you realize what you might be projecting might not be what people are picking up. Someone told me, you have to look at yourself through their eyes, through the lens of colonialism.

Sometimes it wasn’t a problem. Like with Paul Andrew, that interview was on the second trip and we just sat down and I said I wanted to talk about residential schools, but then he started telling me about life in the bush and it was just the most eloquent thing. I didn’t have to prod him at all. I prompted him about the plane, which shifted into his story about residential schools. People are wary up there. You think you’re the first one to ask these questions and you realize you’re not. A lot of people have gone up to do research. The thing that got pushed back at me is, people come here and take my knowledge and I get no benefit from it. We don’t see those people again. We never hear anything from them again. I had to be aware of that. Sometimes people don’t want to talk to you for that reason. Other times they give you the benefit of the doubt. Stephen Kakfwi, the ex-premier, turned out to be a great interview but when I first met him, he was pushing back at me asking, why have you been trying so hard to get ahold of me? He was really irritated. I just apologized to him and he said, okay, let’s just talk. And we did and he was absolutely open. I’m constantly learning more about talking to people. I’m constantly finding out things I didn’t know about communication. Maybe from the outside it looks like I know what I’m doing – and I’ve learned a lot – but I’m always surprised by how much I need to know. Especially in communities I’m not used to. When I talked to really traditional people in the Northwest Territories, I had to learn to make it clear to them how I was going to use the information. If I went to Gaza to talk to people, people go, oh, another Western journalist is here. It was much more complex than I thought it would be. Which was one reason I went.You always have to approach these stories with a bit of humility, because you realize what you might be projecting might not be what people are picking up. Someone told me, you have to look at yourself through their eyes, through the lens of colonialism.

Related to that, you’ve written about going to Palestine and you were a Western journalist, but because of the late Naji al-Ali, they had a context to understand your work – even if you and al-Ali have little in common. Did the Dene have a context to understand what you were doing?

I brought the book Palestine to show them how I would depict them and I have to say, that didn’t really resonate with them. On the second trip, when the first part of the XXI piece was already drawn, people really responded well. They got it. And then would look at it and say, it was more like this actually. But they responded quite well.

How much research is involved in getting those scenes right? You have a reputation for being good at portraiture and getting these detailed backgrounds, how do you capture those details?

In general you’re asking visual questions of people, though that’s certainly not enough in cases like this. In Yellowknife there is a museum and a very good archive of photographs from the twenties to eighties. That period when people were still living in the bush. I relied on that. There were things I was able to find on the web. For example you can find images or videos on YouTube of people building canoes or boats or putting up tents. I’m not an outdoors guy at all, but a lot of those things could be researched. To me the real test was showing that first chapter to indigenous people. I sent it up to someone there who showed it around. I had good comments from people and then I was able to get it into Paul Andrew’s hands. I was quite nervous about that because you’re right, my greatest fear is depicting someone’s story incorrectly. Or in a way that won’t get to the essence of their experience. I got very good feedback from him. That reassured me. Along the way I was asking questions. When you put things in a community freezer, what do the community freezers look like? Sometimes I would be stuck on a drawing and I would leave it blank until I could ask and get information back.

Does that happen a lot? Leaving a panel or a few panels blank because you know you need to do more research?

I don’t do it that often. There’s a page where someone is talking about a community hunt and someone is describing putting meat in storage and I wondered what those structures looked like. I got a few written descriptions and then someone sent me some images. So even though I didn’t draw it from the outside I felt comfortable drawing it in this way. I had enough information that gave me the confidence to draw something where I think: I’ve done due diligence, and I can draw this in a way where someone who knows it won’t go "that’s wrong".

You mentioned that the book began with you wanting to tell stories about climate change. Is that still a continuing interest?

It’s an interest of mine. I would be interested in doing more projects like this. The problem is, I’m almost sixty now and how many more books do I have left like this? I have a lot of interests. So I think climate change or colonialism will be part of another book I’m thinking about, but I don’t want to do something about the sea is going to rise and here’s what it’s going to look like. I think that’s interesting, but it’s been done well by other people. You always look for something a bit off the beaten path somehow.

I read an old interview where you said that you wanted to travel to India and make a book about the Rolling Stones.

[laughs] Guess what’s on the desk right now? The Rolling Stones book. I did one story out of India about rural poverty that was in Journalism. I did another trip there and I’ve written it up. I’ve done all the research. I probably should be working on it. It’s about India and a riot that took place in Uttar Pradesh. Right now I just can’t bring myself to work on it. I might need another trip to India, not so much to do more research, but just to get the taste of India back in my mouth. Who knows when that’s going to happen? It might be a while before I can do that. I have started to draw that project. If I put my mind to it, I could finish it in a year and a half probably. Right now I just needed a break from journalism so I’m doing the Stones book. There’s a lot more going on than just the Rolling Stones.

You do have a book of music journalism.

But I Like It. Unfortunately no one else did, cause no one bought it.

I have one on my shelf!

You and my mother! The Stones book is every idea I’ve ever had in my head that isn’t journalism. Or that journalism cannot tell. Journalism is about things that happened, things you heard, things you saw, things you know. There’s a lot where you can put two and two together, but you can’t prove it. That’s why fiction exists, I think. Fiction can tell certain historical stories so well because it can connect those dots. The Stones book is philosophical and gets into a lot of the things I’ve been thinking about. Telling some stories I never told. I always have a hard time describing it. I just described it to you, but in ten minutes I could describe it to someone else in a completely different way. [laughs] I like to say that it’s the complete synthesis of all human thought and experience told as a book about the Rolling Stones. It’s like I’m seven years old drawing it. It’s so much fun. I can’t wait to get to my drawing table every day.

I’m sure right now having something fun to do is nice.

That’s it. When I think about the India book, that’s a very difficult book. I don’t think my mood right now would work with the India book. It might in a few months. But like you’re suggesting, it’s such a strange time now. I almost feel like if you’re not suffering, a lot of people are. It’s also playing hooky somehow. I keep thinking, is there even going to be a book trade in two years? I hope so, but I want to have some fun before I’m told "no one’s ever going to publish that". [laughs]