The Hollywood and Highland Center is a sprawling shopping mall on Hollywood Boulevard. It’s right next to the TCL Chinese Theatre (formerly Mann’s), and has the Walk of Fame and attendant costumed characters fishing for tips and photos in front of it. The complex is massive and tacky, with a central area made to resemble Babylon from D.W. Griffith’s 1916 epic Intolerance. Among various restaurants and tourist traps, it houses the Dolby Theatre, well known as the longtime venue for the annual Academy Awards ceremony.

The Hollywood and Highland Center is a sprawling shopping mall on Hollywood Boulevard. It’s right next to the TCL Chinese Theatre (formerly Mann’s), and has the Walk of Fame and attendant costumed characters fishing for tips and photos in front of it. The complex is massive and tacky, with a central area made to resemble Babylon from D.W. Griffith’s 1916 epic Intolerance. Among various restaurants and tourist traps, it houses the Dolby Theatre, well known as the longtime venue for the annual Academy Awards ceremony.

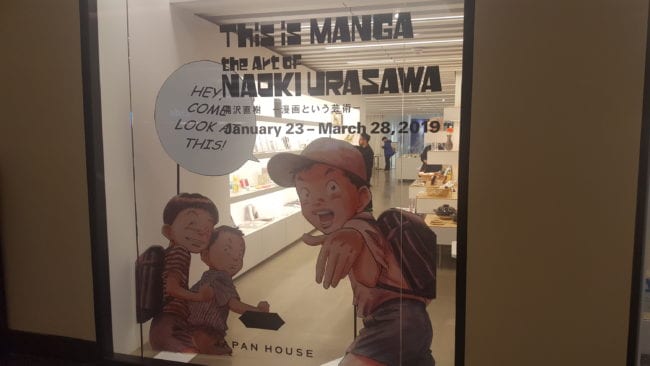

Among the carefully constructed illusions of Hollywood glamour, one might not expect to find a tribute to a genuinely inspired artist. But right across from the main entrance to the Dolby is the store and gallery for the Los Angeles branch of Japan House. An organization dedicated to evangelizing Japanese art and design, the gallery has previously played host to multiple intriguing exhibits, including shows dedicated to architect Sou Fujimoto or prototyping researcher Shunji Yamanaka. Currently, Japan House Los Angeles is paying tribute to a revered comics artist and writer with “This is MANGA – the Art of Naoki Urasawa.”

When I was reading fan-translated scans of 20th Century Boys in college, I scarcely could have ever considered that one day I’d see a billboard advertising an Urasawa show while driving through Los Angeles. After nearly 40 years in the business, the veteran mangaka is getting his very first North American exhibition. The man himself made an appearance for a talk and book signing not long after the January opening of the show, which continues through March 28th. This marks a rare, exciting opportunity for comics fans to experience a rigorous overview of one of the field’s titans, as well as for people unfamiliar with the form to get an excellent introduction to manga.

When I was reading fan-translated scans of 20th Century Boys in college, I scarcely could have ever considered that one day I’d see a billboard advertising an Urasawa show while driving through Los Angeles. After nearly 40 years in the business, the veteran mangaka is getting his very first North American exhibition. The man himself made an appearance for a talk and book signing not long after the January opening of the show, which continues through March 28th. This marks a rare, exciting opportunity for comics fans to experience a rigorous overview of one of the field’s titans, as well as for people unfamiliar with the form to get an excellent introduction to manga.

The Japan House gallery is accessed through its storefront, which is filled with a range of tastefully made, lovingly displayed Japanese housewares, decorations, and books. “This is MANGA!” features some elaborate installations, such as a “tent” of banners bearing series of striking Urasawa panels, as well as a map showing where he’s been published throughout the world. There’s a mannequin wearing the costume of “Friend,” the cult leader villain of 20th Century Boys, from the Japanese movie trilogy adaptation of the comic. A table out front has laminated recreations of notebooks Urasawa kept when he was young, which show off his early artistic progression.

But the show’s main element is a series of three-sided displays throughout the gallery, each of which is dedicated to a specific Urasawa series. With manga-style arrows helpfully telling visitors where to start and how to read, each side follows the process by which a manga page goes from concept to completion. This is illustrated via original art from Urasawa, with a wealth of nēmu (storyboards) provided for the show. There are around 400 pieces of such art in the exhibition, giving patrons a detailed look at the nuances of comic art, and helping laypeople understand how things like layout and framing play into one’s understanding of a scene.

But the show’s main element is a series of three-sided displays throughout the gallery, each of which is dedicated to a specific Urasawa series. With manga-style arrows helpfully telling visitors where to start and how to read, each side follows the process by which a manga page goes from concept to completion. This is illustrated via original art from Urasawa, with a wealth of nēmu (storyboards) provided for the show. There are around 400 pieces of such art in the exhibition, giving patrons a detailed look at the nuances of comic art, and helping laypeople understand how things like layout and framing play into one’s understanding of a scene.

Urasawa’s oeuvre isn’t quite like those of most other manga creators. Many either produce various series and stories at an insanely prolific rate (like the godfather of the form, Osamu Tezuka) or hit success with a particular series and then concentrate on it for many years (like One Piece author Eiichiro Oda). Urasawa has instead focused on a progression of longform series, with the end of one and the beginning of another often overlapping. In this manner, over the course of his career he has made multiple series that are all great, but also each quite distinct from one another.

When you chart the course of Urasawa’s career, you begin with Pineapple Army, a war comic, then go to Yawara!, a sports comic (specifically, judo), then the gentleman adventurer serial Master Keaton, then Happy!, another sports story (this time tennis), then the dark conspiracy thriller Monster, then the sci-fi epic 20th Century Boys, then Pluto, a mature reimagining of a classic Astro Boy storyline, and so on. He’s worked in a wide range of genres and tones, refusing to stick to one track. In this, he bears similarity to Tezuka, one of his biggest professed influences, who also experimented with every style and genre he could.

When you chart the course of Urasawa’s career, you begin with Pineapple Army, a war comic, then go to Yawara!, a sports comic (specifically, judo), then the gentleman adventurer serial Master Keaton, then Happy!, another sports story (this time tennis), then the dark conspiracy thriller Monster, then the sci-fi epic 20th Century Boys, then Pluto, a mature reimagining of a classic Astro Boy storyline, and so on. He’s worked in a wide range of genres and tones, refusing to stick to one track. In this, he bears similarity to Tezuka, one of his biggest professed influences, who also experimented with every style and genre he could.

The most consistent element is Urasawa’s humanism. He’s never made a character he wouldn’t give some extra space for us to get to know a little – both Monster and 20th Century Boys will often set the main story aside for a chapter to focus on some side character. Heroes and villains alike get this treatment, as do some astonishingly marginal figures. His increasingly bizarre, Pynchon-meets-Satoshi-Kon mystery Billy Bat is in large part made of these kinds of side stories. In breaking his body of work down to these isolated scenes, showing off everything from epic confrontations to little conversations in the rain, Japan House does a great job of demonstrating both his versatility and this attention to humanity. Hopefully it will help spur greater American interest in his comics.