WARNING: This interview contains MANY spoilers!!

Since its release at the beginning of October, Monica, the sprawling new book by Daniel Clowes (Fantagraphics, 2023), has been hailed as a masterpiece by numerous reviewers in the mainstream media. Indeed, "masterpiece" is literally the term Junot Díaz used in his glowing New York Times analysis of the book. Noel Murray in the Los Angeles Times called it Clowes' "magnum opus," while the Guardian said it was "pitch-perfect" and compared it favorably to the work of Joan Didion. The Atlantic, the New Yorker, NPR and many other outlets have also weighed in with high praise. A thorough critique of Monica by the Comics Journal's Joe McCulloch can be found here and is highly recommended.

Monica is very good, taking Clowes' post-Eightball work to a new level; it deserves the praise it is receiving. I will not go into depth here to describe the content of the book, as it has been amply covered in those reviews above. I will say that I enjoyed it immensely and that it is a book that both deserves and requires multiple readings. As I mention to Clowes at the start of the interview below, there's a LOT going on in Monica, and you have to pay attention to... well, everything. The book's surface homage to various classic comics genres is a bit of a red herring; the 'genre' chapters serve as time stamps, and give Clowes the opportunity to draw some of his best art yet, but Monica has more in common with the complex literary novels of someone like Thomas Pynchon than it does with any "graphic novel" that I've come across. It's a book that challenges you to think, rethink, reread; it will stay with me for a long time. When I conducted this interview, I was in the middle of my fourth reading of Cormac McCarthy's The Passenger, and found certain passages and themes that evoke in me the depth of wonder that Clowes pulls off in Monica. Or vice versa. Both Monica and The Passenger (along with McCarthy's companion novel, Stella Maris) feature—among many other things—haunted characters searching in vain for the unknowable truths of their familial history, where the reality of the past is ultimately something that is changeable, and may exist only in one's head. If it truly exists at all.

At age 62, and with 40 years of steadily pushing the boundaries of the comics medium, Clowes is at the top of his game. As he told the podcaster Gil Roth, "This is an old man book... I wanted the publisher to list it as an 'OA' novel." And, joking aside, by that he means "mature," as in "fully developed." I can't wait to see where his brain goes next.

This interview was conducted in late September/early October during the 2023 Cartoon Crossroads Columbus (CXC) festival in Columbus, Ohio. Clowes and I then followed up several times via email to clarify some sections. Thanks go out to the CXC staff for facilitating space where we could conduct the interview sessions, especially Caitlin McGurk of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, who graciously let us use her office for part of our discussion. Joining me and Clowes was my wife, Tammi Kelly, who sat in on the conversation and who added several helpful questions and thoughts.

Clowes and I decided to hold off on running this interview until a few weeks after Monica's release, to give people a chance to read the book first. If you have not read it yet, be warned that the interview does contain a number of spoilers.

-John Kelly

***

JOHN KELLY: There's a lot going on in Monica. At first glance, it appears that you're sort of doing your own take on some genre comics that you probably enjoyed in your youth, and maybe still do today.

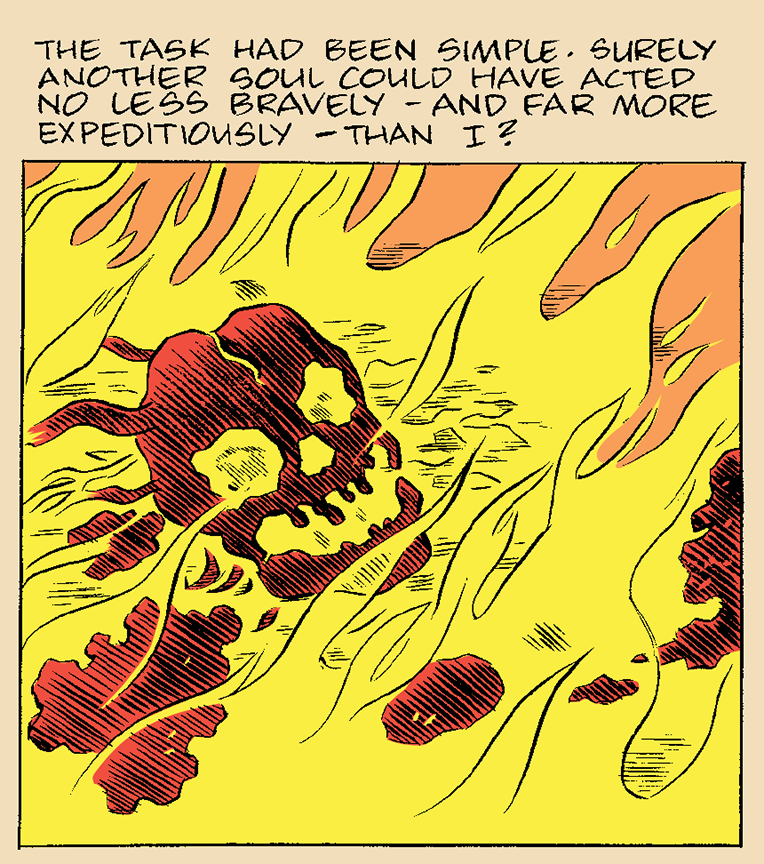

DANIEL CLOWES: [Laughs] Kind of. I had a period where I was going through my old collection and I found all these, like, "off-brand" kind of comics that were really interesting to me. Like these EC knockoffs. There's this company, Superior [Publishing], that was this Canadian publisher from the 1950s and they had just the crudest, scariest comics, done by people you had never heard of. EC comics seem like they're done by these pros, like they really know what they're doing, at the top of their game. The Superior artists are a kind of wannabe EC guys, but there's something off. They seem almost evil, or somehow brain-damaged, you know? It's like the work of PTSD vets coming back from World War II. You can tell they hate drawing comics, they all obviously want to do something else. Nobody wanted to work in comics back then, they all wanted to be Saturday Evening Post guys.

What era were these?

Early to mid '50s.

So they probably were PTSD vets.

Yeah, that's sort of what I imagined. If not, they were some sort of weirdo 4-F guys who got rejected by the draft board. Or they were really old. But the work.... There are certain panels and images that seem so intensely and unintentionally supercharged and powerful, full of true horror and grimness and anxiety. I was looking at those and I was thinking, "I want there to be a comic made up of just those images," where every panel is something you can stare at all day and it has like the weight of a painting, the kind of thing you can look at every day, walking down the hall and go, like, "Oh, I never noticed that tree in the background."

My initial take was that it was kind of like those old DC treasury things from the '70s, where you got a big, fat comic for 25 cents--

The 80-Page Giants.

And you're like, "Oh, I'm getting lots of comics for my quarter here." But most of it was filler. There's no filler in your book, though.

That was sort of my vision for this book, before I even knew what it was about: the idea of a multi-genre 80-Page Giant from like 1957. It would start out with a war story, then a romance story, then a horror story... and I kind of imagined that that format existed, but I don't think it ever did. I don't think there ever was a multi-genre compilation... it would have been really interesting.

I think of the books almost like a sculpture [laughs], where I imagine the final object before I even know what it's about. And as I'm working through it, it becomes... not that. You know, it turns into something else. And so sort of halfway through the book, as I was developing the character and developing the narrative strategy, it was as though the genres all kind of mixed together. They started overlapping each other and they became their own new mega-genres. Like the last story ("Doomsday"), I kind of wanted to make it genre-less, you know? It's as close to uninflected reality as you can have. Which, of course, is a genre, I guess, but... along the way that gives way to something very different.

I think the genre conceit, for me, dropped off about halfway through the book. As I was driving here this morning I was thinking that you have most of the classic genre comics themes—war stories, those kind of goofy 70s DC romance stories, a private eye story, the gothic horror one—but there's no "funny animal" story.

No. I thought about that in the very beginning, but it didn't really work with this book. I sort of did that in Ice Haven, where all of a sudden there's that Blue Bunny character that comes to life, but that kind of thing just didn't feel right here.

At the end of the day, it's a story with a pretty easy elevator pitch--

Is it? I have a lot of trouble with that. [Laughs] I worry that every word I say only diminishes the reading experience.

Well, it's the story of one woman, Monica's, life.

Yeah, it's a cradle-to-grave story about a woman's life. Not exactly a winning sales pitch!

So, at what point did that character come to life for you? For most comics, you're usually looking at a window of time in somebody's life. In this you're seeing the whole arc. You don't see her actual birth, but--

Well, you see her in a baby carriage.

And then it follows her life up until the time of, well, the end of her story. And perhaps, not just hers.

Hey, no spoilers. [Laughs] But I guess by the time this comes out, Comics Journal readers will have read it.

But where did the Monica character spring from?

I think about that a lot. Where does it all come from? What was I setting out to do? But it all just... happens. I had that "Pretty Penny" story kind of in mind. It was a story I had wanted to do for a long time, to try and capture the way my childhood felt, the craziness of it and the kind of inexplicable chaos of that era. And I was like, "I need a narrator for this story," and I realized, it should be through the viewpoint of Penny's baby. And so that's where it began. I had all these other stories in mind, but I wasn't sure it was even going to be the same character. And then, all of a sudden it started to gel, and I was thinking about periods in my own life that felt very separate from each other-- episodic almost, but somehow related, and I began filtering those emotions and experiences through this character, and all of a sudden I felt very free and I began to feel her coming to life and becoming her own person.

And it came naturally that you did it with a woman character?

You know, it was only when I was about halfway through that I wondered, "Should I have made this a male character?" And I couldn't even imagine it. She was so alive and indelible by the time the story started to come together.

She was a real thing.

Yeah, it becomes a real thing... and if I wanted to change it... [Laughs] It occurred to me that maybe I didn't want to have two books in a row that were just a woman's first name [laughs], so I thought very fleetingly about changing it, but it was impossible.

Knowing what I know about your life, there are certain elements in Monica that are almost like autobiography, but it's layered beneath the surface. Joe Matt just died, and I'm not asking about doing autobiography in the way he did it—über-intimate stories about things that perhaps people don't really want to know about—but have you ever considered doing a more traditional autobiographical story?

I just don't trust myself to do it.

But none of your narrators are reliable anyway! [Laughs]

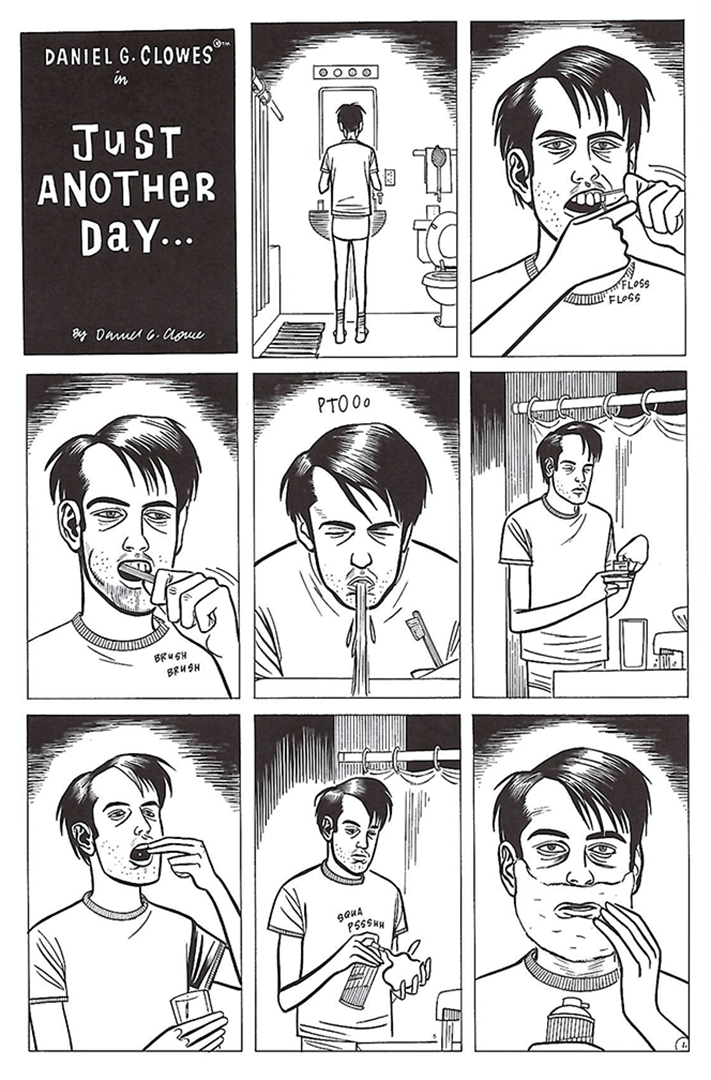

No, I know, but to me, I could only do it if I lied far more than I would in fiction. I used to do strips in Eightball that were like, "Me! Talking to the audience!" but they were sort of a parody of the idea of autobiography, and I never thought anyone would take them seriously as being about the actual "me." I thought it was like, clearly I'm pretending to be a character or an archetype... but then people would take it seriously, like, "But you said in this story that this happened..." It was all so complicated.

I don't know. I would never say never, but I find the idea very constricting. I wouldn't want to make myself look good, even if it was a rare instance where I was writing about something I actually felt good about, but I also don't want to make myself look unintentionally bad. You know, like the way Joe [Matt] over-accentuated his badness for laughs. That feels as dangerously untruthful as making yourself look good, even though it enabled Joe to make some of the greatest comics of all time. It's just too many things to work into the mix. Fiction is much easier.

The Penny character has some elements of your mother.

Yeah, she has sort of the same dynamic as my mother, in a way. Same sort of-- someone entering this new world that was presented to people in 1967, '68, and just embracing this whole way of life, and then seeing that freedom dissolve into chaos. In my own family, my parents divorced when-- I don't even think I was a year old. I don't even remember them together. Before I was born, my parents were involved in auto racing. My father was an engineer and built his own racecar and taught my mom how to work on cars. She really took to it, and she started working with him as his mechanic. They hired a driver to drive in all these kind of small races on the Formula Junior circuit, and then my mother left my father for the driver. Which I never knew... I knew they had divorced and she remarried, but I didn't know he was their driver, or that my dad even really knew him, until after she died.

You only learned that recently?

Yeah. I figured out about my stepfather being the driver of my dad's car by looking through old racing data online (where they list the owner and driver of each car in the race). I had always thought he was just some random guy my mom met during their racing days in the early '60s, like a racetrack acquaintance of my parents with no other connection to them - but it looks like he was driving for them for a while before I was born. He also left his wife for my mom, so it was a big mess. His death occurred at the preliminaries for a race in Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, in 1966, when I was 5. His car lost control and rolled over and he was crushed, an accident that probably wouldn't even cause a bruise in a modern safety-equipped car. When he died, my mom was basically like, "That's it. I'm never going to be close to anyone else ever again." [Laughs]

TAMMI KELLY: Well, that's the underlying theme of Monica, right? Every time there's a deep connection, something tailspins. In the final part of the book, I was imagining something almost like the rapture, almost like Hell's rapture. Like what comes up from the bottom--

Yeah. That is what I had in mind.

And the vehicle that brings this uprising to the Earth is the radio, which was Monica's way of connecting-- and Monica buries the radio, but when she digs it up at the end of the book, things don't go well. [Laughs]

Right. Very good. You should let her do the whole interview. [Laughs]

JOHN KELLY: Monica is a bit unusual in that it's a book that I think really needs to be read more than once.

Yeah. That was my goal, to create a book that you finish and then go back to the beginning... "I'm going to read this in a completely different way." [Laughs] Ideally, I'd like everybody to have a different reading of it. The response really has been like a Rorschach test. People see in it very different things. I have very close friends—a couple—and one of them said, "I almost couldn't deal with it. It was so depressing," and her partner was like, "I found it really uplifting! I thought it showed such a humanity." Just totally different responses. When I was working on the book, I had no idea what the response would be. I didn't show it anybody for the whole seven years.

At what point in the process did you know how it would end?

Pretty early on. I had the ending in mind. I mean, I'm always trying to live the book through the characters, and then if the ending doesn't make sense by the time I get there, then I change the ending. But this one felt like it was moving in a certain inevitable direction.

There's a book by Richard Yates called The Easter Parade where the first sentence is "Neither of the Grimes sisters would have a happy life," and then over the course of the next 200+ pages you see that the narrator wasn't kidding.

[Laughs] I've never read that. Sounds great.

My point being that you could go back and see that end of Monica is spelled out right in its first story.

Sure. Several times, in fact.

And then there's all kinds of hidden surprises. Different characters reappear throughout the book in different guises, as well as familiar images and themes from your earlier work. Did that come naturally, or was it through the process that it started to make sense to do that?

I mean, that's why it takes a long time to do this. If I added up the time it takes to just draw the book, it's probably two or three years at the most. But it's letting things sit around and endlessly rewriting until it's almost like an incantation to the spirits. It's not a way that I could have worked my whole career, but I really wanted to do one book where I let things come into place exactly as perfectly as they possibly could. Some things I waited for four or five years with a blank panel [on the drawing page], you know, waiting to see what happened. And then one day, it's just like, "Oh, It's obvious what goes here."

You took your time with this book and an awful lot of work went into the design. In his review, Comics Journal editor Joe McCulloch poses his theory about how even the way that the pages of Monica were color treated was purposeful, that the varying coloring and shading of the chapters holds meaning as to the type of story it contains.

I'm not sure I want to reveal the "secret meaning" behind the color schemes, but they are very intentionally designed to create certain connections between the stories, among many other things. I spent a full year coloring the book, and two-thirds of that time was recoloring over and over as my understanding of those connections got deeper and deeper.

Were you drawing the pages as you went along, while the story was still developing?

I'm drawing the things that are fully figured out, or that feel unchangeable, and I have the pacing in my mind for some of the other stuff, but there's a lot of pages and panels I leave blank along the way. I did not draw the stories in order, for instance. The last story, "Doomsday," I drew last, but everything else was in a somewhat random order. The "Pretty Penny" story was, by necessity, first.

Well, it's interesting because the first story, the war story, flows into "Pretty Penny," [but] then there's the gothic story, "The Glow Infernal," and I was like, "What the hell is he doing here?"

Yeah, you're sort of in a game of telephone with the first two. You leave the first one and then you're with the young woman Johnny's talking about in the foxhole, and then you leave that and you're not sure where you are.

It was at that point where I wasn't sure if they were connected, or really what was going on. I was stumped by that one at first because I had read a lot of those, like, '70s Charlton horror comics as a kid, and they're just creepy, weirdo stories that you would come away puzzled by. But I was a kid and just went onto the next one. But if I were to go back and read them as an adult, and think about the writers who made them, I'd be like, "What in the world was this person thinking? Were they mentally ill?"

It's so funny. It's like literally the opposite of the way that I work. They were like, "Ok, I've got 20 minutes to write an eight-page story." [Laughs] "I know it doesn't make sense, but who cares? The readers are a bunch of idiots, and I'm only getting 40 bucks."

And I'm like the opposite, where every panel has to have years of thought put into it. There's endless rewriting, and redrawing, and all of that.

That's the funny kind of stuff that as a writer you sometimes wonder about. Sometimes I think, "Well, if I had just went with the first--well, not the first draft, but third or fifth or tenth draft of this story, would anyone notice the difference?

Yeah. In a lot of my books, I would say no, not really. This one? For sure. When I finish a book, and send it off to [Fantagraphics editor] Eric [Reynolds] to read for the first time, I'm usually happy with everything in it. And then when the book comes out, all of a sudden I can see everything absolutely clearly, every little mistake is magnified, and all the writing seems like the sentences literally don't make sense, like the words have no meaning. It can take years to get over this, for the two disparate versions to merge.

Yeah. I've done readings of my work, like a short story, where it's an old piece, and I've literally stopped reading and taken out a red pencil to the published piece and made changes to the book.

[Laughs] "I've never read this out loud..."

Well, no, I've read it out loud, probably a hundred times, but you change as a person. You really went through all of that recently when you were putting together the Eightball anthology. Going back and rereading those old pieces probably for the first time in a long time. It must have been weird.

Sure. When I look at those, I just think, well, I was young and I hadn't learned to do what I wanted to do, but at least I put in the effort. There was a time in the early '90s when all of a sudden Eightball was really popular in the tiny world of "alternative culture," as they called it, and everybody was like, "We really want you to do our cover for our magazine or our comic." And I remember I had a month where I had like six or seven covers that I had to do. One was for Denny Eichhorn's Real Stuff.... He sent me this cover idea and I just agreed to do it so he wouldn't keep browbeating me, and I remember doing it sort of angrily in a single day, totally uninspired and just hoping to get him off my back. And now when I go through my old comics, I see that one and it's just like a stab in the gut. Why did I do that? I should have never done something where I didn't put my full effort into it. And so that pains me, but my own stuff where I did as well as I could, that's fine, even if it looks terrible and seems amateurish. It doesn't bother me.

There was a shift though. I always loved your stuff. I bought Lloyd Llewellyn #1...

Did you really? [Laughs] When it came out?

Yeah, when it came out [April 1986]. There wasn't much else.

Not a lot coming out back then. You were like, "What the-- a black and white comic!?"

Yeah. I would buy Love and Rockets, the Comics Journal, I dunno. Flaming Carrot, Reid Fleming, Neat Stuff... I liked the retro design of Lloyd Llewellen.

There are a lot of forgotten ones, like Stig's Inferno. [Laughs] That was a Vortex comic. And all those Piranha Press comics...

Yeah, but when you made the transition from Lloyd Llewellen into Eightball, that was a big jump. Obviously. It looked completely different... it was a completely different thing.

Yeah, it was exactly what I wanted to do. I did Lloyd Llewellyn as a series because I did a single Lloyd Llewellyn story and sent it into Fantagraphics and Gary [Groth] was like, "You've got to have a main character. Just do this character," and I was like, "But that's all I have, that one story." [Laughs] So, Eightball was much more what I always wanted to do, more of a crazy MAD-like underground anthology thing. Gary and Kim Thompson were very skeptical, I remember. "Okay, we'll publish it, but don't count on anything."

Well, at the time that they came out, some of those early Eightball stories, to me, seemed like they were weird just to be weird. I loved them, but it seemed like you were trying to find your way.

I can say that that was not at all the case. Those stories were very real to me at the time, and still convey exactly the way I felt back then.

I was living in a very depressed state of total alienation at that time. And so those are all very emotionally intense to me.

What I'm getting at is that your storytelling ability has continued to grow as you've gotten older.

It seems like it would have to after 40 years.

It doesn't happen with everybody.

It's weird. It's very easy to get burned out, I guess.

You've matured and you're doing very literary work now, which is somewhat rare.

[Laughs] I hate to use that term. "Literary Comics," that sounds so boring. Because it's really the opposite of literary in a way. It's picture storytelling, and the words are really there to inflect and propel the images.

A movie can be literary.

Yeah, it could be, but if someone says, "Oh, this movie is really literary," I'm probably not rushing out to the theater to see it.

With [Monica] I wanted to make it visual... I really wanted to make it almost eye-melting in parts.

And it is. But it's also not, "In this panel this happens, in this one that happens." There's a lot more going on under the surface. Which is a theme for the whole story, right? But it's also, in some ways, an easy read.

That was my intention. That you could read one story at a time and get something out of it...

And that's exactly how I read it. I read it and then I read it again, and by halfway through the second time I realized there was a lot more going on. And by the third reading even more things became apparent. When I was in grad school at Sarah Lawrence's writing program, we would do a thing called "demystification" where you would read a story or book three times. The first time, you just read it to read it, to get the plot. The second time, you'd look for patterns the writer was using. The third time, as you read it, you tried to make sense of those patterns. I was doing that with Monica.

It's becoming a lost art, that kind of close reading. To me, as an author, to read someone's response that's written that way is so much more rewarding than-- than just a sort of critical assessment. It's almost like people judge art by its commercial appeal rather than any emotional or aesthetic response. It's like when people respond to movies based on their box office. There's nothing I'd rather read than a deep analysis of a book or movie I love, rather than just a declaration of the critic's opinion. I'll happily watch a two-hour video about color symbolism in Vertigo, or something...

How has your experience writing screenplays informed your comics work, if at all?

It allowed me to feel better about writing comics. In writing screenplays, you're writing for somebody; you're writing to get a movie made, which involves compromises. It's a collaboration from the get-go. There are a lot of things you can do in a screenplay or a novel that you can't do in comics. You can do a lot of editing. In a comic, if you've drawn the whole thing, you can't omit a character, for example, or rearrange panels, so you've got to plan ahead a bit more. So, there are limitations, but also [with comics] I won't have somebody read it and say, "Well, I just don't see us getting the budget for that. Can you cut all the outer space scenes?" I can do whatever I want. It's all me doing every little thing. And even the greatest director, if they were to direct one of my screenplays, it would be something they did. It's nowhere near as satisfying.

But you've done that though.

I have. I love movies. Movies are my second-favorite art form. I watch a movie every single night, and often I think I've already seen every great movie ever made. [Laughs] And I love the idea of being part of that, but to try to get to that is almost impossible. When something great comes together, it's almost pure luck. There's too many people involved, especially nowadays. It's incredibly difficult, and I'd rather focus on what I do.

Right. What I was asking was, has the experience of writing screenplays changed the way you write comics?

It might have unconsciously. There's certain structural things that you do in writing a movie that you have to be aware of. Just sort of identifying your protagonist and getting into the story and all that stuff that becomes ingrained through a lifetime of watching movies and TV shows. I try to not think of that stuff when I'm doing the comics. I try to not be bound by the, you know, Syd Field Definitive Guide to Screenwriting or whatever. And maybe by being aware of what I'm trying to avoid, and trying to be unbound to that stuff, I'm still somewhat bound to it. I don't know.

You weren't writing these last few books with the idea of making them into movies. Monica or Patience may or may not be made into movies, but--

I don't think so. Who knows? If the Coen brothers come to me, I'll think about it.... Or if you can get [Andrei] Tarkovsky back from the dead [laughs], of course. I would just like somebody who is an actual artist to make the film and let them do whatever they want with it.

Would you turn down a hack director if they approached you?

Yes.

Have you done that?

Oh yeah, many times. Every book has been approached by directors that I've turned down. I've had a few where the studio owns the rights to the book and they've tried to get it made by a terrible director, and I have to threaten to publicly denounce the movie and stuff like that.

Is that what happened with the Patience movie? There were articles in 2016 saying that it was about to happen.

What happened was the production company, without telling me, told a director that he could do it... and I had to say, yeah, I don't want that to happen. And, thankfully, they realized that I was going to be a pain in the ass, so they didn't pursue it.

Or somebody could just steal your work.

Yeah. My dream is to have all my books turned into like bootleg Korean sci-fi films [laughs]... I want them to be where it's almost like you can't even tell that it's from one of my books, just a totally different culture taking the tropes of it and turning it into something new.

Some Japanese animation people turned Jim Woodring's work into a cartoon. I think he loves it, but it's absolutely nuts. [Laughs]

That's perfect. [Laughs] That's my dream.

But you've had this done. An actor stole your story "Justin M. Damiano."

Oh, Shia [LaBeouf].

What could he have been thinking? "Oh, it's just a comic book... nobody will know... it's not a real thing..."?

One day, I dunno, seven or eight years ago... it was a December morning, an acquaintance of mine said, "Oh, congratulations. I didn't know about that Shia LaBeouf film." And I was like, "What?" And so I go online, and there was this link, "Shia LeBeouf has released his short film on..." It was some website that had a daily short film. And so, I start watching, thinking maybe he mentions my comics in the film or something like that, not knowing what it was, and then it was like... I remember for a few seconds thinking, "This is actually pretty well written"... and then all of a sudden I was like, "Wait! I wrote that!" [Laughs] It was exactly word for word. And I sat there thinking, did I somehow give him the rights to do this without remembering? What is going on? I was so confused. And at the end it said "A Film by Shia LeBeouf." I went and got my copy of the book, it was in this anthology that Zadie Smith edited called The Book of Other People. It was just a very short vignette. And I read along and rewatched the film... same shots, exact same wording, except my character's name is Justin Damiano and he changed it to Howard Cantour. As someone later pointed out, if you go on Fairfax Avenue in Hollywood, there's Canter's Deli and next door is Damiano [Mr. Pizza]. So he couldn't even, you know, leave the block, [laughs] in terms of making up his own thing. But word for word, otherwise. So I was just in a confused panic. What do I do? What's going on? And some magazine, I think it was Buzzfeed, reached out to me and asked what was going on, and I said... "Believe me, I have no idea what this is." And then all of a sudden I was getting calls from CNN, "Can you be on tomorrow morning?"

I was like, I don't want to be on CNN and talk about Shia LaBeouf. [Laughs] It was my worst nightmare.

Did he do an okay job of your story?

No. He just transcribed what I did and took credit for it. He got a good cast because he knows people.

Talking about casting, throughout Monica there are characters that are... familiar looking. Some of them are TV actors from the past, some are characters that look like ones from stories you've done in the past. But toward the end of the book, you have a character who looks suspiciously like you.

Which is funny, because I think only my friends will kind of get that. Like a lot of people who don't know me that well didn't get that. Nobody has brought it up, and I thought everybody was going to be asking me about it. You're the first journalist who's said anything about that.

I won't be the last. I noticed it immediately, obviously. "And so, Dan is drawing himself here..."

It's a character named Stan. It has nothing to do with me. [Laughs]

But it's... not you, because...

I'm married. [Laughs]

You're married, and you wouldn't be--

Hitting on some woman at an Airbnb.

Right. By the time the Stan character and Monica are talking, they're noticing... oh, they have a lot in common in their lives. And since you, yourself, share some characteristics with Monica, it was kind of like you seeing you talk to yourself.

I was talking to my therapist a lot about what I was doing with this book while I was working on it, trying to understand my own unconscious motivations, and at one point he said, "It seems to me that you're trying to make a friend." I'm always talking to him about how my childhood was so complicated and so unlike anybody else's I've ever met that I can't really connect in that way with anyone else. It was such an odd little indescribable world. And the more I get into telling the story, the more it seems like I'm just making it up. Like, there are many more complications to it. And so it was like I was trying to create somebody where... we could meet and have a sort of kinship based on a similarly-complicated childhood. [Laughs]

Well, loneliness runs through a lot of your work.

In this book, I think of it as not loneliness, but aloneness. Like, I don't know if [Monica] is lonely. Some of my other work is more about loneliness and the longing for connection.

End papers in a book can say a lot. It's not always the case, but it is here. Monica opens with a spread that kind of looks like drawings from an old children's encyclopedia or something, showing the history of the world. It starts with amoebas and ends with the Beverly Hillbillies.

Which only people our age will get. Everyone else... like all the kids will go, "I have no idea who those people are."

They'll recognize Hitler.

Right. They may even recognize JFK. But this [points at Beverly Hillbillies panel in the book] they will not. Obviously I thought it was funny to end there, but I also thought that when we were that age, there was nothing more important than television, and the number one show for many years was The Beverly Hillbillies. And that show has certain reverberations with the world of 2023.

And then you end the book with a familiar-ish apocalypse, which is a theme that is mirrored throughout the book... but then I was wondering, what was going on in your head when you were doing this book? There was a lot of crazy stuff going on in our country.

The book is in part about dealing with chaos, and it felt like chaos was and is reigning supreme.

In terms of what's going on in the world right now—as a father and a human being—how bad a shape do you think we are we in right now?

Oh, I think we're in quite terrible shape. I used to see a way out of it. I can remember being a young man, doing the early issues of Eightball, and I felt like it was kind of a joke to complain about things and focus on the negative, because on some level I felt like humanity was on this kind of upward arc.

It felt like we were moving slowly and bumpily to this more peaceful world. I didn't think that was going to happen quickly, but that was the kind of vague arc of those years. I felt like things were progressing incrementally forward. During the '90s things started feeling very stagnant, but it also felt like progress wasn't moving backwards. Sort of coalescing. And then in the last 10 years it suddenly feels like... I don't know how we get back to anything that feels like we're going to move forward. It feels like we can't put our energy into... preventing global warming or whatever other hellish catastrophe we're facing because we have to put all our effort into just stopping the people who want to make things worse.

As a parent, that just amps it up.

Yeah. It's terrifying. I just can't image what the future will be. It feels like it's going to get very, very chaotic and incomprehensible, beyond the capacity of my old man brain...

TAMMI KELLY: In Monica, you also play with the notion of "being chosen." Monica describes herself as an "unwanted fetus of two random fuck ups," but when she's with the cult, she feels as if she may be the "chosen one." And then, misinterpretation runs throughout the book. It's what Krugg, the artist, is saying on page 91: "A true artist, it seems, is admired only through an accident of misinterpretation."

It's like a lottery.

JOHN KELLY: Misinterpretation and randomness. Your life could have turned out this way, your life could have turned out that way, your life is this, right now but it could have been different.

Yes. And you look at the flowchart of life and it's-- well, it could have very easily been different had I not, for example, met my wife. Where would I have gone? I would have moved somewhere else, I would have met someone else, I would have a different kid... everything would have been very, very different. And it's just... one random day that changes everything. It's debilitating to think of life in that way, but that's the case for everybody.

I have many friends, and I'm sure you do too, who are cartoonists who constantly make the wrong life decisions over and over.

Not just cartoonists.

Yeah, but cartoonists-- the ones who are genuine artists, especially. Joe Matt is a perfect example...

Well, it seems that once he made a decision, he never changed it.

He had, like, an ethos that he lived by and... died by. It was unchangeable. But I hesitate to say anything about Joe's life, because I think he was perfectly happy up 'til the very end. He always seemed upbeat, very energetic - even though if you were to describe his life to someone else they might think, "Oh my God, he's in the throes of major depression."

Depression, but as I get deeper into a very large project I'm working on about the life of Justin Green, I see some of what was going on with Joe as pure obsessive-compulsive disorder. An infantile... rigorous to rigor mortis story... I liked him very much, but he could be maddening.

Seth had the perfect description [in TCJ's memorial piece about Matt], which was like, [Joe] is like a 14-year old boy who came home from school and has found out his parents are gone for the night and he's just like, "I can do whatever I want! I'm gonna live it up!" And then he just kept that going 'til, like [age] 60.

Seth's piece was... harsh, but... beautiful.

Beautiful and heartfelt and the best of its kind. And he captured how he really felt about Joe.

You've said many times that your were painfully shy growing up and even into your adulthood...

I still am, though not nearly as bad as I was as a kid.

When I first met you, or not even met, but saw you, I guess... it was during the Hateball Tour in the early '90s when it came to New York at a party at Robert Sikoryak's loft. You looked pretty miserable and I don't think we even talked, but I remember thinking, "Wow, this is tough for him." And now you're, seemingly, at ease in large crowds of people.

I've gotten to the point where if I talk to people who understand, who know about comics and art and things like that, I can feel pretty comfortable.

I've seen interviews with you, though, with people who... I wouldn't necessarily say are all that familiar with your stuff...

That's purely adrenaline and I can summon it up, but I might afterwards lie in bed for two days recovering. It's exhausting. But I've gotten to the point where I can identify, "These are my people," and I get something out of it. It's not the same. Before it was almost like a chemical thing, where all of a sudden I would be so self-conscious and terrified of rejection that it was really hard to talk to anybody. I didn't want to be judged or rejected. I had to get to know somebody really well before I could open up.

But this weekend, you'll be surrounded by people here [at CXC] who may look at you and go, "Oh, it's that Hollywood comics guy," and there could be a certain amount of jealousy.

I mean, nobody's that jealous of an old bald guy, [laughs] except maybe another old bald guy. When I was like 25 to 35, I'd go to comic conventions and there would be, like, Will Eisner, Jack Kirby, Harvey Kurtzman... I would have never in a million years thought of being jealous of them, but I was definitely resentful of a lot of artists my own age...

Well, that came across in a lot of your earlier work. Maybe hatred is too strong a word, but a lot of it was full of that scathing, hilarious commentary on... various things. Sometimes it was the comics world, sometime it was just... anything.

Yeah, well, a lot of it was just exaggerated for effect. I've always found that people who are constantly angry over little insignificant things—like bad architecture, or modern pop music—to be funny. Like, I love those kind of people. [Laughs] Most people are like, "Oh, I can't stand to be around that guy, he's always complaining and negative all the time," but I have a very high tolerance for it.

In those cases you can just be the observer. No one's looking at you because the other person is making such a spectacle of themselves.

Yeah, I can live vicariously. My friend Richard Sala was a prime example. I never interacted with him online because I'm not a Facebook guy. Everybody who knew him from online would always say stuff like, "He was the sweetest, nicest guy. He was the most helpful..." I was like, Richard Sala? To me, he was the most sputtering, angry... the prickliest, smartest, sharpest critic there was... and I loved it. I loved that part of his personality.

Last night, after your talk here at CXC, you were signing books for about two and half hours. Given your shyness, I can't imagine that was comfortable.

I'm not shy one-on-one with anybody.

But you had hundreds of people on line waiting to meet you.

I don't look at the line, I never play to the crowd, I just focus on the one person in front of me and try to give them all of my attention.

This has just got to be very different than in the early days when you're sitting at a table and not a single person comes up to you.

Or it would be like, "Oh, Dan Clothes. I don't know who you are, but can you sign this program with everybody else's signature on it?" It would be that kind of thing.

With your heart surgery in 2006, have you had to make lifestyle changes as a result?

I was born with a defective mitral valve that caused the heart to leak over time, and due to its poor function it had to work extra hard and got quite enlarged, like an overdeveloped muscle. Luckily, I had this incredible hardcore old-timer surgeon who was able to do a full repair, after which the heart shrank back to normal size. It was a pretty major thing—I have what looks like a 14-inch chainsaw scar on my chest—but the heart itself is in great shape, though it obviously went through some wear and tear before the surgery, so I have to be a little mindful of taking care of myself. Like, I don't want to end up getting long COVID, for example.

But having gone through that, do you think it's changed you in other ways?

Oh, yeah. I felt like I had a dividing line in my life. It felt like I had died and then been given a second chance. You know, I could see what death was like, and I came out of it and still to this day, I think it's kind of a miracle I'm still alive. Like, God wanted me to die at 45 or so... I was programmed to die and, pre medical intervention, I would have. A very ugly death too. So, whenever anybody is like, anti-science, anti-vax, I just have no patience for that at all. Medical science absolutely saved my life.

Your mother and your brother both died during the making of Monica. How old was your mother?

She was 88. She had the same heart defect that I had, but she was diagnosed much, much later than I was. I already had had my surgery, and so she didn't get as good as a repair as I did because she was so old. She was like 75. And it lasted her 13 years...

If she had lived, what do you think she would have thought of your new book?

Whatever she would have said would have been super-annoying. [Laughs] She would never have been able to look at it like, "Well, this is your personal vision of this." She would have bristled and argued that I was actually a happy child or whatever, or more likely she would have totally shut down and avoided me. Part of me, I think, hoped maybe she'd read it and we'd have an actual discussion, but that's not something we ever did.

Your brother Jimmy also died--

He died right before her.

But he would have been a relatively young-ish man.

He was 66 when he died. He was a heroin addict since he was 15, and unapologetically. He was like a William Burroughs type, one of those guys who was like, "I've got it all figured out, I do it the right way, I live life exactly as I want." It was very depressing... he was the smartest person I've ever met in my life. He was in prison for a long time because of drugs—he was making meth in my grandma's basement for a while and got busted—and while he was there they tested his IQ and they said he had the highest IQ in the history of the California penal system. [Laughs] I mean, he was just beyond brilliant. He made me feel like an idiot all my life.

You guys did some comics together. They were in BLAB!

That was right after he got out [of prison] the first time. He had written these stories while he was prison and I was trying to get him on his feet. He did a story for BLAB! in around 1987 or '88 that Richard Sala illustrated, actually, that was about Donald Trump being assassinated! I remember mentioning it to Richard after Trump got elected and he was like, "Don't tell anyone about that!" He was convinced that the CIA would be banging down his door. [Laughs]

I wonder how your experience growing up changed your approach to parenthood?

It made me think about my own childhood, in terms of the parenting. And I'd think, what were [my parents] thinking? You know, because it just seemed normal. It felt like, well adults have their own lives and that's all that's important, and you're just this sort of ancillary product that they have to kind of work around. I spent years sitting in my mom's auto shop while she fixed cars all day and I just sat there and, like, played with wire [laughs] for nine hours.

If you had the time travel device, like the one in Patience, and you were to go back to 1987, and you're lettering Judo Joe--

[Laughs] That was Chic Chumley, and that had nothing to do with me.

And drawing some things for Cracked or whatever, and you met your younger self... could you have imagined that this would be your life, at this point, here in 2023?

Well, if I were to go back just a few years before that, where I was in art school or right out of art school, and trying to get work as a comic artist in any way... if I were to go back then and tell myself, "Yeah, when you're 62 you'll have your 10th or 11th book out, you'll have made a living as a cartoonist your whole career..." I would have melted in tears. It would have been beyond my wildest dreams.

But it was what you wanted.

Absolutely. But I was just making it up. It was just a fantasy, not a real job that existed back then or anything.

All of our lives could have gone in so many different directions. You could have ended up—and you probably would have been happy at the time—lettering or inking for Iron Man or something.

Maybe. If I had been better.... If I had more facility, you know, as an inker, when I was like 18 or 19, which some people have, naturally, I could have easily gotten swept into that world. And then once you're in it... I would like to think that I would have gotten out of it right away, but you don't know.

At that time in alternative comics, with Eightball and Hate at their peak, there were a million different titles with many different creators. If Ghost World hadn't turned into a movie, your life could be different.

It would be different. Once Eightball became kind of a hit, that felt like a turning point. I felt like maybe somebody does want to read these kinds of comics. I'd look at the people who are a little older than me, all the RAW people, Charles Burns, Drew Friedman... they seemed to be thinking the same thing. There was a feeling in the air that maybe comics were turning into something really interesting. Before that, in the 70s, you'd see Heavy Metal and stuff like that. It was really not my thing, exactly. It was beautiful in parts, but could never read most of those stories... and still, it felt magical at that time. Like there was suddenly all this new terrain that we were exploring.

And it really was an exciting time.

It was. It's hard to imagine anything like that now. [Comics] feels like the art world, like post Abstract Expressionism or maybe Pop Art, where everything becomes fragmented and there's no main cultural art thing that's happening, where everything is divided smaller and smaller into subcategories like neon art, performance art, or whatever. I don't know. It feels like that happens to every art form. It gets broken up into smaller niches that somehow have less and less impact.

Yeah, well there's really nothing that has come around in any form of art that exploded things like the way [James Joyce's] Ulysses did, or T. S. Eliot did with The Waste Land, and that happened around 100 years ago.

No, it's true. Or the Armory Show--

The 1913 Armory Show. With comics—whatever term you want to use, "graphic novels," whatever—there are comics that have risen above the rest. Like with every art form, the vast majority of comics are not very good. There are some that have risen to excellence, and a much smaller number that have have risen to the level of fine art. There's really none that have risen to the level of The Waste Land or Ulysses. There's no Moby-Dick. I just wonder if that can ever happen, or if it's even possible at this time in history to make something that revolutionary.

Yeah. Eliot and Melville were writers. To be a comics person, to do that, you'd have to be a combo of Picasso with Eliot. You know, the odds of that are so small. William Blake is maybe the one example I can think of...

In comics, [George] Herriman came the closest.

Yeah, he did, for sure. That is probably our Waste Land. And he wasn't anti-Semitic, so there's that too. That's a feather in his cap. [Laughs]

So, yesterday we were on a tour of the archives at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, and we were surrounded by original Herrimans and Winsor McCays and... every time I'm there, it's very humbling.

Very humbling. I come into something like this [CXC] and I'm seeing all the young cartoonists and thinking, "I've been doing this for 40 or 50 years, and I know a thing or two," and then I'll see a Winsor McCay Little Nemo Sunday page that he did in like a day, and it's just like, "Okay, fuck it. Why do I even bother?" [Laughs]

Yeah, but there may come a day, sometime in the future, that your stuff will end up in a place like this.

Or not. One of my favorite things about art history is that if you ever read older critical assessments of any movement as it's happening, there are always names amid the greats that you don't recognize. It's always like, "Picasso, Matisse, Braque, and Jenkins."

Who the hell is Jenkins?