As with many Americans, times were hard for me in 2010. My income depended on freelance work. After the financial washout of the 2008 recession, most of that work was gone. In the middle of two graphic-novel projects with my talented collaborator David Lasky, I had no income, save the occasional small gig that came my way. I let go of the apartment I had been renting in Seattle's Capitol Hill neighborhood and was technically homeless for a couple of years. To quote Rudolph Toombs's lyric from his song “One Mint Julep”, I don't wanna bore you with my troubles. I survived that hard time, as did friends who lost their homes and jobs. I’m doing somewhat better these days, all things considered.

This interview was conducted on May 24, 2010, after a mainstream comics-oriented website had offered me a weekly paying gig doing a column for them. My knowledge of, and interest in, modern mainstream comics is minimal. I proposed a weekly interview column in which I'd talk shop with comics creators. I didn't have to know (or like) a creator's work to discuss how they did that work. As a comics creator, I shared the basic tools of the trade. This patch of common ground seemed large enough to make the column work.

Finding willing subjects was a challenge. Every mainstream pro I contacted declined (or never responded). I was granted interviews by Kim Deitch and Harvey Pekar. The site was okay with these two creators but stressed that I needed to get more mainstream pros to talk with me.

It became clear by June that this column was a lost cause. Without interview subjects, an interviewer is stale-mated. I continued my work on the Carter Family and Oregon Trail graphic novels with David Lasky and wondered what I'd do with these two interviews. Deitch gave a lively account of his working rituals and ended with a rousing encouragement to young comics creators to work their butts off and make the world a better place.

I intended to do a follow-up call with Pekar, whose comics I'd read and enjoyed for two decades, and chose two or three specific stories to discuss in depth. Before I could reach out to Pekar again, the news came on July 12th, 2010 that he had been found dead in his Cleveland residence.

To my best knowledge, this is the last interview Pekar gave in his lifetime. I attempted to shop the interview around but had no takers. I was preoccupied with staying afloat and finishing two demanding, elaborate graphic novels. Thus, the audio of the interview, alongside Deitch's, sat on an external hard drive.

In the nine years that have passed, Pekar's influence on comics may have waned a bit. Autobiographical comics continue to be created, but few of them share Pekar's picaresque bent. One notable exception is Max Clotfelter’s “The Warlok Story”, which is Pekar-worthy in its unflinching depiction of a darkly funny incident. Harvey remains comics' genuine working class hero. His best stories are gems of observational humor, street-level wisdom and fearless depictions of the ordinary. I hope his best work will never fade from sight.

This interview reminds us of Pekar's opinionated, outspoken character, as he discussed Middle East politics, meddlesome editors and the marginalization he felt as a writer whose work, in his own words, received “good critical response, but nothing ever sold real well.” In 2010, Pekar was a retired government worker having to continue to write comics to supplement his small pension. He remained game for new projects and sought to expand the subject matter of his work.

Thanks to James Gill, who recorded the discussion at his home, and to Christina Hwang and Emma Levy for transcribing the raw interview.

Frank Young: The movie American Splendor showed your approach to doing simple layouts for stories. Do you tend to write the text first before you break them down into comic book pages?

Harvey Pekar: No, no. A lot of times, most of them I have in my mind. I've pretty much memorized what I want to use, down to the dialogue. And I just sort of talk to myself, or read what’s in my brain, and write it down. I can’t remember the last time I ever wrote the text out for something without breaking it down into images.

Do you carry stories around in your head and develop them that way?

If I got a story, and I’m not going to do it real fast, and the memory is going to fade, then I’ll make notes on it. Generally, I try and do stuff as quick as I can.

After you’ve written something down, do you do a lot of revisions? Or is what you put down on paper pretty much the way we see it in the final version?

Pretty much. I edit it when I transfer it from my memory to paper. And, yeah, as I got them down on paper I’ll look it over.

Since a lot of your stories are personal reminiscences that involve other people, do you have to go back and talk to them about events that you’re going to depict?

I don’t ask them, “Do you remember what you said at this moment?” As a matter of fact, now I’m so isolated socially that there’s nobody to talk to. I’m just writing about stuff as it happens to me. And of course I’m old, so I’m also writing about a lot of stuff that’s not autobiographical.

How have you researched these newer projects?

How have you researched these newer projects?

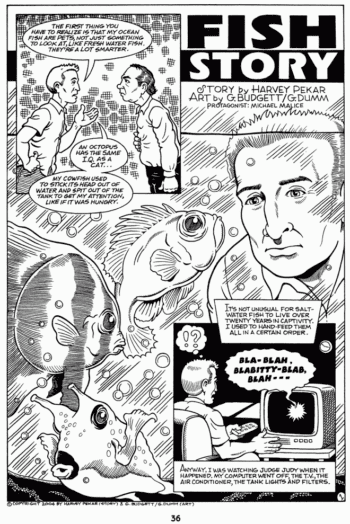

For a couple of them I just interviewed people and did the thing from notes. That’s the book about Michael Malice [Ego and Hubris: The Michael Malice Story, Ballantine Books, 2006; illustrated by Gary Dumm] and the Macedonian thing [Macedonia: What Does it Take to Stop a War?, Villard Press, 2007; co-authored with Heather Roberson and illustrated by Ed Piskor]. I even give co-authorship to the woman who told me about her experiences in Macedonia. But that’s about it.

How do you communicate your ideas to the various artists that illustrate your stories? Do you give them a lot of notes?

Yeah, well, I put notes on paper, and then I’ll call them up. I talk to everybody on the phone. I’ll go over the story and tell them what I’m looking for. And I always say, “Look, if you run across something that you can’t understand, or if it’s illegible, just call me. Or I’ll call you in a couple of weeks if I don’t hear from you, just to make sure everything is fine,” you know?

That’s an important part of my communication that a lot of people don’t see. And if it’s a real long piece, I’m dealing with somebody maybe quite a few times. Like if it’s a graphic novel. I’m working on this graphic novel now about how I lost faith in Israel [Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me, published posthumously by Hill & Wang, 2014]. You know, I’m Jewish, and I write about when I was a little kid, and all I heard was Israel’s side of the story from everybody. Everybody in my family, and my friends, and their family... You just heard one side of the story. And then if you believe you’re one of God’s chosen people, that’ll settle things for you, sure.

As time went on, and I became independent, and I formed my own ideas, I got pretty upset with Israel. I’m at a point now where I think that their foreign policy is self-defeating. All this for nothing, you know. First of all, the Arabs have a beef, but nobody wants to hear about it. Which was that the whole Middle East used to be under Turkish control and the Turkish empire. But the Turks were stripped of all that Arab territory after the First World War. Provisions were made for everyplace else, like Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan. It didn’t happen overnight, but there were provisions made for self-government. But in Israel’s case, everybody was hyping the hell out of their position, and talking it up... politicians and everything like that. So the British had a mandate at the League of Nations: “take care of Israel until there could be a vote on it in 1947 in the UN.” And instead, war broke out in ’48, and the Jews won the war. People around here, in the United States, where Arabs were mistrusted, as they still are today. People said, “Well, good for the Jews.”

The Palestinian Arabs got treated worse than any of the other Arabs. They didn’t even have a stab at self-government That was one of my points; that [point] takes a long time to develop. And then their use of force… it’s one thing if you use force and you really gain something. I’m not for going out and having a war, or anything like that, but if you’re going to have a war, it should get you something. And these wars that Israel’s fighting, they’re going to have to keep on fighting them as long as they exist, unless they change their policy. I went into a lot of detail, and I did a lot of research on it. Then I sent it into the editor, and the editor wanted me to restructure it, and in the mean time I got together with a real good illustrator. His name is JT Waldman.

Do you have a working title for the book?

No, not really. I just refer to it as “The Israel Book,” or “How I Lost Faith in Israel;” something like that. I don’t know exactly. It’s going to be historical stuff, plus they wanted me to mix in a whole lot of my own personal experience, and how I personally changed my mind.

[My opinion changed] over the years. It wasn’t a one-day thing. When they had the Six-Day War, in 1967, Israel had all of this territory. It used to be called the Occupied Territory—the Golan Heights, and all those other territories. And I thought, “Okay, their strategy's going to be...they’re going to try to negotiate with the Arabs. They’re going to hold the land out in a land-for-peace deal.” In other words, we'll give you back the stuff, but there's gotta be some kind of control or an independent body–somebody that monitors you guys, or maybe even sets up a military position to guard the borders... I think a lot of Jews thought that, at the end of Six-Day War... the fact that the Jews had this takeover. But then, one prime minister–and he was a labor prime minister, the left-wing party, said “Okay, we’re going to let some Jews go over and live in the West Bank.” That was crazy. That was throwing away the whole opportunity–I mean, [this happened] just because the Arabs didn’t come to the Jews at the end of the Six-Day War, which was hugely humiliating to them, and say “Okay, alright. We’ll make any deal you want.”

It’s stupid to occupy that territory because hopefully you're gonna make a two-state solution. And then you won’t have to go through the shit that they had to go through in Gaza when they just had a relative handful of Israeli settlers over there, and they had to fucking fight with every one of them to get them out of there so that they could hand it over to the Arabs completely. And how are they going to get those Jews out of the West Bank? They should’ve never let them go over there. That was my immediate reaction. If there was anything that was a real big stab, it was that. I thought: “these guys are crazy.” They must be intoxicated with their victory, because now they think the sky’s the limit and they don’t think they've got to negotiate with the Arabs. And that’s the way it’s worked out. Now they don’t even want to agree to a two-state solution which has always been paid lip service to.

I think this will make for a much talked about and controversial book.

Oh, listen, man. If you say “boo” about the Arabs to other Jews they call you a self-hating Jew. I know I’m going to be in for a lot of shit but, I mean, I expect it. I’ve seen it happen. God! The littlest thing, you know? And all these Jews that are liberal about everything else will go insane. They'll start writing letters to the New York Times and all that stuff. So, I’m expecting to take a lot of shit. On the other hand, I think I’ve got some good political points that need to be publicized around the world in places where the Israeli Jews are still regarded as God’s people. It’s something I’m real interested in, man. It’s a long piece that you can sink your teeth into. So there’s a couple reasons I want to do it, even though I know I’m leaving myself open for a lot of criticism–automatically, no matter. If you question anything that an Israeli politician does, if he's right-wing politician, you’re going to get letters, you know. People are going to go berserk.

Have you experienced any differences of opinion with JT Waldman?

No, we discuss everything. He’s a guy that’s lived [in Israel] and that’s one reason that I chose him. But he’s also a very good artist. He's got two things out: Megillat Esther [The Jewish Publication Society, 2005], which is about Queen Esther and about why Jews celebrate Purim. And then, he and I did a comics introduction to a book by Arie Kaplan [From Krakow to Krypton: Jews and Comic Books, The Jewish Publication Society, 2008] about the history of Jews in comics, you know, one of fifteen million books about the history of Jews in comics…

The styles that [Waldman] uses are pretty different. It's much more cartoony [for Kaplan's book], which I think is appropriate. The drawings for Megillat Esther are very very complex…

Does an artist’s drawing style affect the way you approach a story? And, as a subset of that question, do you write stories with certain artists in mind?

When I’m writing a story, I’m thinking about who I’d like to work with. But up until real recently, I haven’t had much of a choice. Starting from when I put out American Splendor and I could only pay 25 bucks a page. A lot of guys in my position wouldn’t have paid anything, you know, and they could have gotten people because [the artists] wanted exposure. But I mean still, for 25 bucks a page, you gotta just take what you can get.

You were getting really good people right out of the gate with American Splendor...

Yeah, well, some of the people were good and they needed the publicity. But then there were some people that I didn’t think were that hot that I just had to work with. I don’t want to mention any names. It was a 60-page book when I first put it out, and that’s a lot of pages to fill for a guy in my position. There was only one guy that I just thought really fucked me over. That’s about how much he should’ve gotten: 25 bucks a page. He could have done [the entire story] in a night, I don’t know. It was a real poor job and I never worked with him again.

Do you give the artists a lot of leeway in how they illustrate your stories?

While they’re working on it–the story’s unfolding right in front of them. And especially now; I’m working with some good people and intelligent people—people who know what they’re doing. I want them to stay with the outline of the story, but if they want to change something–they want to make two panels out of one panel or one panel out of two... that’s okay with me.

But text is another thing. I want that to be pretty much the way it was. But [with the artwork] I give them a lot of leeway. I’ve learned over the years to trust just about everybody I work with.

The thing is–maybe some of them weren’t great artists, but most of the people that I worked with have been pretty intelligent. If they changed something, I’ve always had the option of saying “oh, no, that’s not the way I laid it out.” I don’t know if I’ve ever changed anything unless I've been working for somebody and they said “no, we got to get this in,” or “our readers won’t know what it’s about unless you put in this.” That’s happened to me recently. It doesn’t really change the direction of the story–I gotta stick in some extra crap, or explain something, readers maybe never heard of this person or that person.

Since you’ve moved more from self-publishing to working with Dark Horse and Abrams and other publishers, have you found you've had to make more changes or make more clarifications to material?

Well, actually, the person I'm thinking of, who I don’t want to mention right now because I’m still working with him and he pays real good, you know? And it doesn’t kill me to make the changes. He wants to stick his oar in every place, it’s just ridiculous, man. So many times, he’s just dead fuckin' wrong.

There’s this one autobiographical story about when I was a kid and the illustrator used as a model the street that I was living on. And the guy said, “These houses are way too modern” and they’re 1920s houses. And I’m going, “Where does this guy come up with this shit?” So we refused to make a change with that. He didn’t say anything. But usually I try, if it’s a minor change, not to start a war with somebody. There are times when it’s just ridiculous, at least in my opinion. There are just some times when you can’t deal.

Has your creative approach changed since you did your first stories? Are you still drawing stick figures with word balloons?

Yes, I just did one yesterday like that. I'm looking right at it.

So, that’s obviously the method that works for you.

Yeah, that way I can control the timing of the story and see how I want to time it. What I think works and what doesn’t work–maybe I should put in a dialogue-less panel, or maybe I should split up the statement that this one guy is making into two or three panels, maybe two panels with a no-dialogue panel in the middle or something. That’s very useful for that purpose, yeah.

I take it that you’re not part of the computer age.

I don’t know how to work one. I’ll tell you what, I’m not saying this to be modest, I can’t fucking do anything with my hands. I got kicked out of the Navy because I couldn’t wash my clothes right. I mean, I really wanted to be in the Navy. I couldn’t find a job. Times weren’t as bad as they are now, but I mean, they were bad. And for a guy like me, who’d just come out of high school and didn’t have any special skills to offer... I was looking to the Navy as a last resort—and as a good resort. My cousin had gone in the Navy–he lived upstairs from me—and it was a worthwhile thing for him.

You’ve worked with Robert Crumb, Frank Stack, Joe Sacco, and Dean Haspiel. This is a wide range of art styles: from photo-realists to others that are more cartoony and “comic-y.” How does that affect you as a creator? Do you tailor stories to an artist’s style?

You’ve worked with Robert Crumb, Frank Stack, Joe Sacco, and Dean Haspiel. This is a wide range of art styles: from photo-realists to others that are more cartoony and “comic-y.” How does that affect you as a creator? Do you tailor stories to an artist’s style?

Well, the first thing I want to do is write a story. And then afterwards I can–depending on who’s available. I try and give it to the person who’ll get it in the right style–what I think is the right style, or the closest to that person that I can get.

Does your approach vary between books like the Israel project that you’re working on and stories that are about your own life or people that you know?

I’m going to give you more than you asked for.

That’s okay.

When I was publishing one [American Splendor] a year—and especially with Dark Horse, when it was a comic book a year but it wasn’t a 60-pager, it was a regular-sized (36-page) comic. That was okay. To put out 60 pages a year, it wasn’t too much. But after I retired from work, I found that I couldn’t make enough money to support myself from my pension, which I had stupidly not really checked out to see how much it was [going to be]. I had known people who worked for the federal government, and they all seemed to be getting a lot on their pension after they retired. I thought that I would, too. “They’re not going to leave me in the lurch.”

But guess what–I forgot that they based the pension on your income. And I never got a promotion when I was working for the federal government. I never wanted one; I had exactly what I wanted. So, I was at the bottom of the pay-scale when I started and when I ended. Even that plus Social Security wasn’t enough. So, I had to write to fill in the extra money that I needed.

This movie came along [2003's American Splendor, starring Paul Giamatti as Pekar] and I hoped it’d give my career a boost. I didn’t dare think that it could, because people weren’t really publishing my work because it didn’t make any money. A lot of stuff got good critical response, but nothing ever sold real well. But the movie came out and it was kind of a hit–it won a Sundance award. I don’t take any credit for that. While it’s based on my stories, there were a lot of unusual things that they did in that movie that I didn’t tell them to do, or that I hadn’t thought of, that I really thought were ingenious.

So without asking me, to publicize the movie, HBO, who produced it, got hold of Random House and sold them on a project to reissue some of my work. I didn’t think it was gonna do me much good because I’d been on Late Night with David Letterman and it never did a damn thing for me. It never helped me at all. I don’t know of anybody who ever told me they bought my book because they saw me on David Letterman, even though I was pretty popular on David Letterman. To my surprise, the book sold respectably enough. And that, plus this reputation that I have for influencing a whole generation of artists–that’s just what some people have written, you know, you don’t have to believe it. But I had a good reputation. And couple that with the fact that the sales weren’t abysmal... I was able to get these graphic novel gigs.

In terms of sales, I’m really not doing that great. Especially in these troubled economic times we’re living in. It's getting harder and harder for me to get gigs and stuff. I’ll get a job and it’ll be for less than what is considered standard payment, even for a beginner, let alone a [laughter] generational-influencing artist like me. That’s what I’ve gotta go with. At this point, I’m still getting some money, and I’m also getting these engagements to speak at colleges and stuff every once in a while–get $500 or $1000 or something like that, including your plane fare and hotel.

So, that’s kind of a perk right there. I've managed to figure out a way, at least for now, to keep my head above water. But the thing about it is, I’ve got to write, completely or at least partly, four books a year. You know, books that are about 150 pages each. So, I might have to write as much as 600 pages.

Not only that; even if I retain the quality of my autobiographical stories, you know, having to write way more...you just run out of stuff. You start repeating yourself. And I don’t wanna do that. There’s all this other stuff that I’ve been interested in all my life, like politics and music. So, I was able to start writing some biographies and history stuff. I was involved in a book that was about the history of the beat generation...

And you’ve done some memorable pieces about jazz musicians.

Yeah. So that’s what my position is today with regards of why I started writing about other subjects. I like to write about other subjects and I didn’t start out as a comic book [creator]. I started out as a jazz critic when I was 19. [Pekar wrote for Down Beat magazine for almost a decade in the 1960s and '70s.] And then I later did literary criticism...

With the amount of work increasing, do you spend the same amount of time per page writing, or has that changed?

Maybe not per page. I’ve obviously gotta turn out a lot more pages, so I gotta have more time writing but… I’ve really got all the time I need right now. And if I’m not making my deadlines, it’s my fault. I’ll say that right there. There’s no excuse for me not being able to turn out even 600 pages a year.

Are there any artists that you haven’t worked with so far that you’d like to collaborate with?

Yeah, but I don’t wanna mention any names. There’s a whole lot of people, there’s people I don’t even know, that probably I’d be thrilled to work with if I saw their work.

Have you had people contact you wanting to work with you?

Yeah, all the time. Usually it’s like...there’s some 18 year-old kid that’s going on a fishing expedition, thinking, “well, I’ll write him and tell him how much I like his work and naturally he’ll be charmed by me and write me back and say, ‘gee, where have you been all my life? I’d like to have you work for me forever’,” or something like that. I don’t get a tremendous amount of mail, but a fairly large percentage of it has, like, a hook in it. At the end, they want me to do something, even if it’s just to sign an autograph and send it back.

Do you do autographs?

Yeah, I do that stuff. It's no trouble. I’ll make a personal appearance, I’ll do autographs, and I’ll let people take pictures of me with them, because I don’t wanna seem like a big grouch or anything like that. I think that’s within reason–a person buys my stuff, okay fine, let them take my picture, it’s no skin off me.