Charles Augustus “Gus” Mager (1878-1956) is known primarily for his Sunday newspaper comic Sherlock Holmes spoof, Hawkshaw the Detective, which ran off and on from 1913 through 1947. But there's more to Mager -- lots more.

Mager was a gifted humor cartoonist who held his own with with the likes of George Herriman and Jimmy Swinnerton, creating over 30 strips that are genuinely charming, beautifully cartooned, and totally forgotten by today's audiences. Mager's delightful drawings and goofy comedy remain fresh and interesting. Mager's comics contain the same sort of greatness we find in the more famous newspaper humor comics, such as Peanuts and Calvin and Hobbes -- an intelligent mind having a great deal of fun with cartooning. However, his career is not well understood, and perhaps this is partly the reason his work has not received much attention. The comics of Gus Mager are ripe for rediscovery and appreciation.

Gus Mager was also an accomplished painter associated with the Ashcan School that included John Sloan and George Luks, famed American artists who also worked as newspaper cartoonists. Throughout his lifetime, Mager's efforts were divided between his comic strips (which one supposes paid the bills) and his paintings.

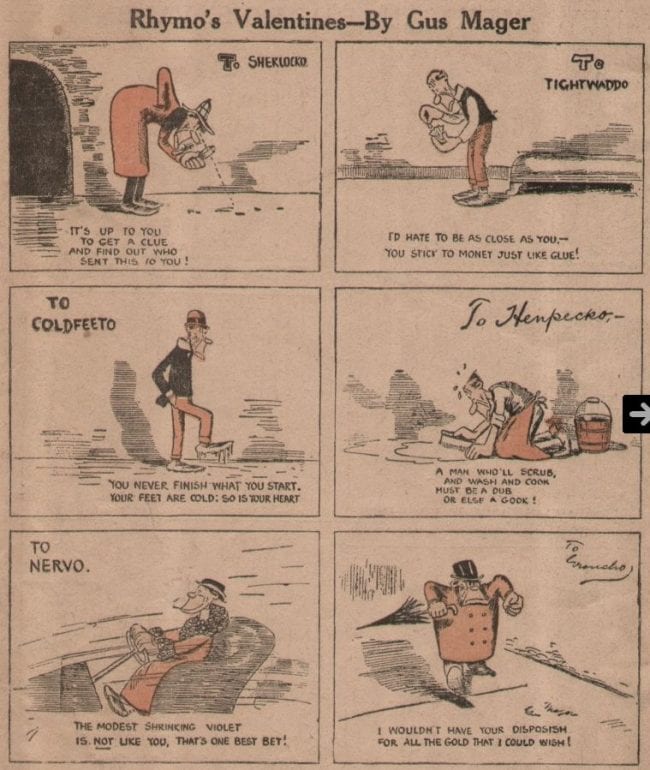

In the first couple of decades of the twentieth century, Mager's comics had a wide and appreciative readership. Some of his goofy gags caught on and became popular trends in themselves, as was the case with his series of comic strips (which ran under various names, and is often referred to as “Mager’s Monks”) that featured various human-like monkey characters with names that described their typical behaviors, such as Tightwaddo, Coldfeeto, and Groucho. Adding an "o" to nicknames was, apparently, a brief popular craze inspired by Mager's strips. It was from Mager's Monks comics that the Marx Brothers, as well as other, now-forgotten Vaudeville comedians, derived their names.

Mager’s style was a mixture of grotesque distortions and cute characters, stemming from the late 1800s Germanic school of cartooning fostered by Wilhelm Busch. Mager's writing shows a keen insight into the foibles of human nature, and it is this aspect that makes much of his work accessible, and enjoyable to a modern reader. Mager's comics from 1904-1913 anticipate directions that comics, animation, and children’s books would take in ensuing decades.

In his cartooning career, Mager created well over 30 series, mostly black-and-white dailies. Many of these creations were spawned between 1904 and 1913, sometimes only running for a few days or weeks before being discarded. Mager’s restless early career was not uncommon. Early newspaper comics allowed for a great deal of playful experimentation with new strip concepts and formats. After about 1915, Mager settled into his long-lived Hawkshaw the Detective series, with some notable experiments every few years, such as the full page color Sunday Main Street (1922-23).

This column offers a broad overview of of Mager's work as a cartoonist. My next column will look at three of Mager's extraordinary works in detail, the "lost" Sundays of 1904-1906.

First Comics: Jungle Society (1904-1906)

Gus Mager was born in 1878 to German immigrant parents in New Jersey, and grew up enjoying the cartoons of Wilhelm Busch and Karl Arnold. Thus inspired, he sold cartoons to American magazines in his teenage years. At some point in his mid-twenties, Mager landed a position as staff cartoonist at the Hearst-owned New York American and New York Journal. These papers provided spot cartoons, art and comics to the other Hearst papers around the country.

Comics historian Rick Marshall has said that Gus Mager pronounced his last name as "Mah-ger." This information was passed on to Marschall from John Dirks who knew Mager. Mager worked for John's father, Rudolph, as an assistant on The Katzenjammer Kids, a comic strip directly inspired by Busch's cartoons. Gus Mager can be seen, along with Rudolph Dirks and Lyonel Feininger (The Kin-der Kids, Wee Willie Winkie's World) , as a primary contributor of the Germanic influence in early newspaper comics in America.

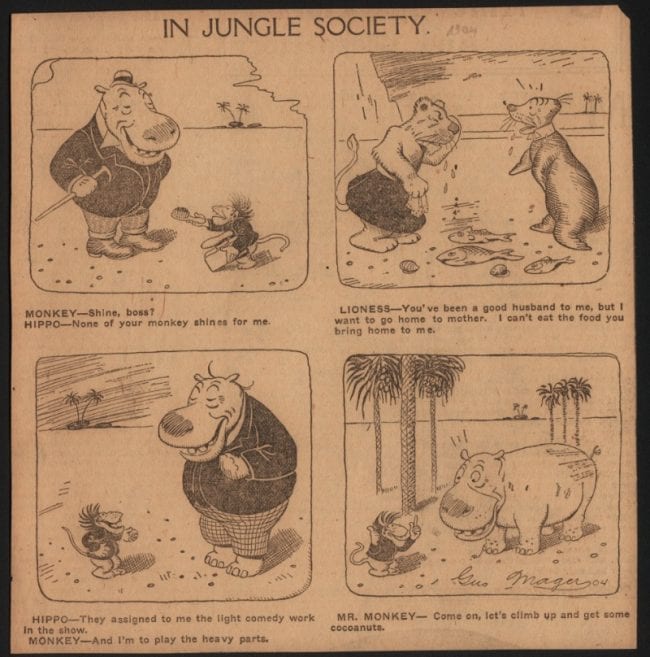

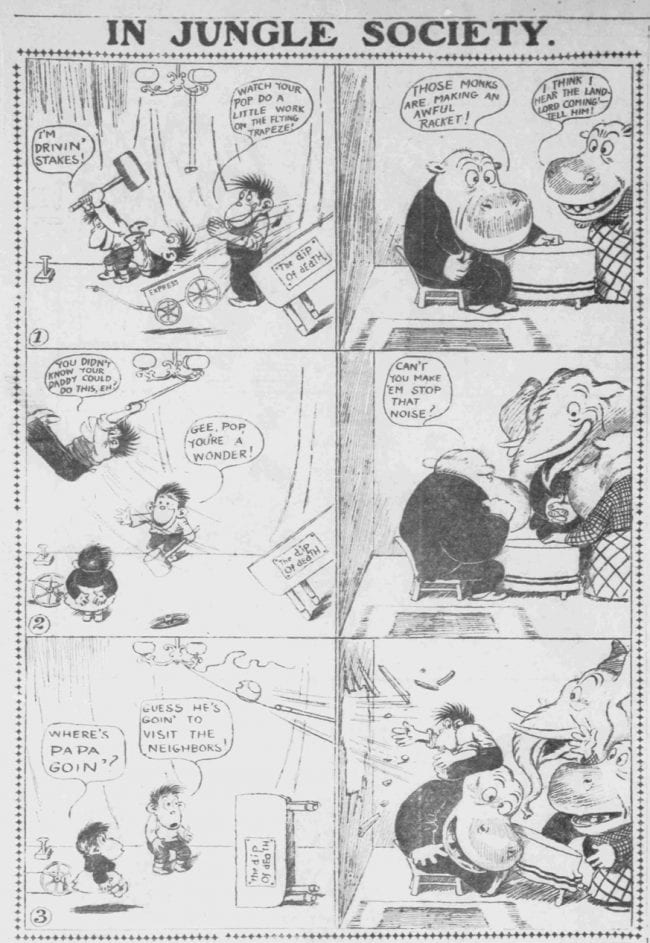

Mager's comics first appeared in newspapers in April, 1904. From the start, he seemed inclined to draw charming hippos and monkeys, possibly influenced by the work of fellow Hearst artist T.S. Sullivant whose humorous animal cartoons were highly regarded then, as they are now.

Where old-school illustrators and magazine cartoonists like Sullivant created detailed single-panel cartoons rendered with virtuoso technique, Mager seemed to understand the need for a different kind of visual approach in multi-panel sequential comics. His clothes-wearing animals are simply drawn, but no less charming. One of his first strips was called, alternatively, Jungle Land, The Jungle Society, and In Jungle Society.

It began in 1904 as a series of separate panels with typeset captions and featured animals in their au natural state. By 1906, Mager's Jungle comic evolved into a sequential strip. The animals began to wear clothes, Mager's drawing style became more refined, his humor became more slapstick, and his comics more sophisticated. In one example, a panel border is also used as a separating wall between two rooms. Four years later, in 1910, George Herriman would build an entire strip around this concept, called The Family Upstairs, and which spawned Krazy Kat.

Mager’s Monks (1904-1913)

In a circa 1920 issue of Cartoons magazine (in which his name is misspelled as "Gus Mayer"), Gus Mager's early interest in jungle animals was documented (note that Mager's name is spelled "Mayer," perhaps the author's spelling of how heard the artist's last name pronounced ):

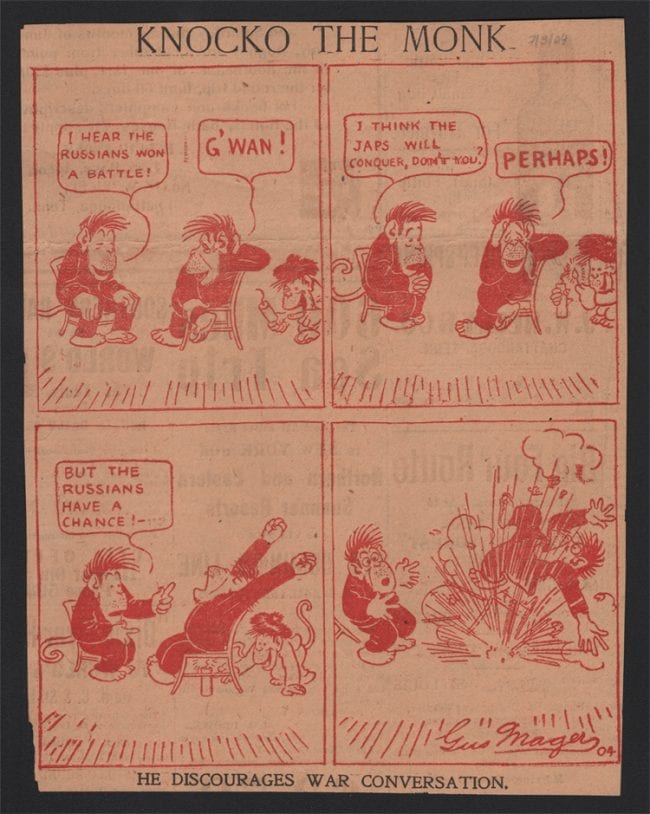

"Gus Mayer (sic), the author of the famous "Monk" series, always did like to draw animals. Hippos and monkeys were his favorites, and in order to indulge his hobby to the fullest extent he gave up a position as a jewelry designer, and went to the New York American where they allowed him to make animals by the yard. Finally somebody suggested that he take the little monkey which appeared usually in the corner of his weekly "jungle" page and develop him into a full-fledged comic character. So Mayer (sic) dressed up the little beast, clipped his tail, and introduced him to polite society as "Knocko the Monk," a gentle satire on those individuals who are always taking the joy out of life." (“Comikers and Their Characters” by William P. Langreich - Cartoons Magazine,1915)

According to American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide by Allan Holtz (University of Michigan Press, 2013), Mager launched his Monks comic strip on April 22, 1904, which would make it concurrent with, and not subsequent to In Jungle Society.

In any case, Mager continued his Monk strips at a rate of two or three a week from 1904 through 1913 (Holtz cites March 6, 1913 as the last one), sometimes switching them out for episodes of In Jungle Society, and other funny-animal creations, such as Reynard the Fox. Mager's signature gimmick of names ending in “o” created a fad, similar to Rube Goldberg's 1909 Foolish Questions series. Various writers have speculated Mager was inspired by Latinate Italian in his naming scheme, but it is arguably possible that he was combining his two favorite, trademark animals: the hippo and the monk.

It's also of interest that, in his autobiography, Harpo Marx clearly states the comedy team of The Marx Brothers derived their names from Mager's comic. In his autobiography, Harpo Speaks! Harpo Marx talks about the popularity of the strip and its notable influence on entertainment culture of the time:

“In Rockford, the four of us and a monologist named Art Fisher started up a game of five-card stud, between shows. At that time there was a very popular comic strip called "Knocko the Monk," and as a result there was a rash of stage names that ended in "o." On every bill there would be at least one Bingo, Socko, Jumpo, or Bumpo. There must have been a couple of them on the bill with us in Rockford and we must have been making cracks about them. because when Art Fisher started dealing a poker hand, he said "A hole card for -- 'Harpo.' A card for 'Chicko.' One for --" Now that he'd committed himself, he had to pass "o-names" all around the table. The first two had been simple. I played the harp and my older brother chased the chicks. For a moment Art was stuck. Then he continued the deal. A card for 'Grouch" (he carried his dough in a grouch bag), and finally a card for "Gummo" (he had a gumshoe way of prowling around backstage and sneaking up on people). We stuck with the gag handles for the rest of the game and that, we thought, was that. It wasn't. We couldn't get rid of them. We were Chicko, Harpo, Groucho and Gummo for the rest of the week, the rest of the season, and the rest of our lives.” (Harpo Speaks!, 1961)

In the study of American popular culture, there can be no clearer and more direct lineage between screwball comics and the movies than that between Gus Mager's Monks and the Marx Brothers. In Gus Mager’s “Monks” comic strip, there was also a “Groucho,” but unlike the Marx Brothers’ meaning (a moneybag – called a grouchbag in their era), Mager’s monk was an ill-tempered, grumpy fellow. For example, in a two-tier daily from May 24, 1908, Groucho is plagued by an inability to escape the sounds of “The Merry Widow Waltz,” a popular song of the day.

As stated earlier, it's possible that Mager was playing off the words "hippo" and "monkey" when he hit upon his popular naming scheme. However, according to a May, 1910 Bookman article, the original inspiration for Mager's "o-clan" came from James. J. Montague, a fellow Hearst staffer who wrote humorous verse, columns, and short stories.

“It is significant that the first of this clan to be pictured was ‘Groucho. The idea for it came to James J. Montague, who did not hand it over to Mager until he had first extracted enough inspiration from the cloud which hung over the artist to give him the dark plot of a light verse.” (Some Figures in the New Humor, Bookman, May 1910)

Thus far, the original verse of Montague that features Groucho remains at large. In any case, before he was done, Mager created a rich cast of one-sided, but richly entertaining comic characters, including Tightwaddo, Henpecko, Coldfeeto, Nervo, Rhymo (who always spoke in rhyming couplets), Boneheado, Forgetto, Goodthingo, Shrimpo, Hamfato (a conceited actor) and Joko (a compulsive practical joker).

Because the titles of these daily cartoons varied, comics historians and reference works tend to refer to the whole lot, published between 1904 and 1913, as "Mager's Monks," although the strip never carried that title.

Starting around 1910, Mager created several Monk episodes that featured cross-over appearances of his various characters. Each of his monks represented a particular human neurosis and putting them together opened up endless new comic possibilities. For example, Tightwaddo irritated Groucho, and Henpecko was a constant source of amusement for Jocko (Joke-o), while everybody was irritated by the brazen Nervo.

Enter Sherlocko and Watso (1910 - 1913)

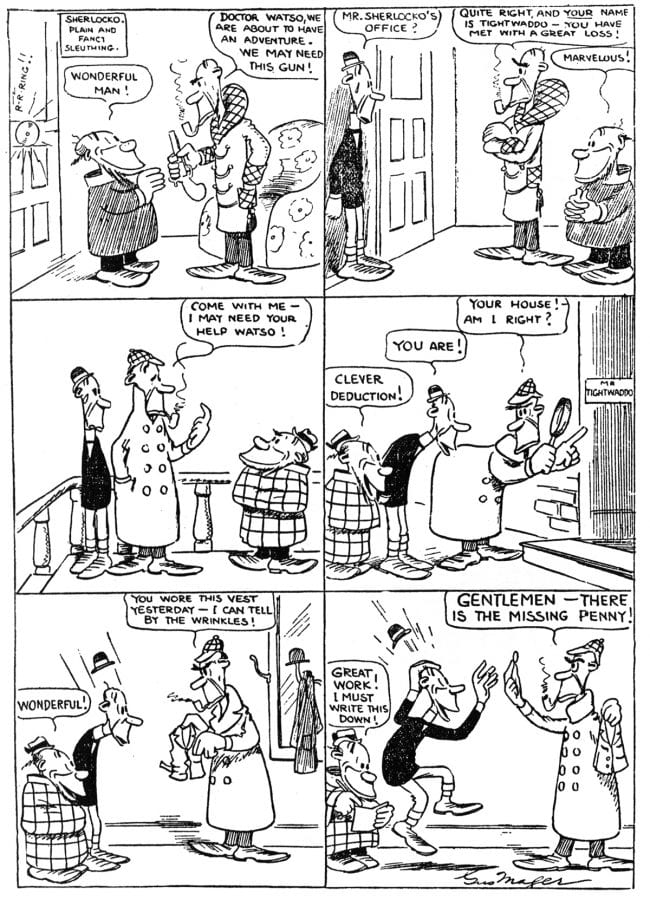

On December 9, 1910, Gus Mager introduced a new O-suffixed character into his strip that would impact his career for decades to come – a parody of Sherlock Holmes, called “Sherlocko.” Holmes’ admiring and not-too bright companion and chronicler, Dr. Watson became, perfectly, “Watso.”

According to comics historian Bill Blackbeard (author of the 1981 Sherlock Holmes in America), Sherlocko the Monk was “one of the earliest Holmesian images in comics.” The famous detective creation of Arthur Conan Doyle made his debut in 1887. By the time Mager satirized him into his strip 13 years later, Sherlock Holmes had become a worldwide phenomenon. Mager’s strip benefitted from the popular adoration of the Sherlock Holmes character, which has continued to this day.

In the debut episode, “The Adventure of Tightwaddo and the Missing Penny,” the concept is already fully formed, with a complete case depicted in a single episode. The solutions of Sherlocko’s cases are built on the particular quirks of one of Mager’s Monk characters – with Henpecko, Groucho, Tightwaddo, and Nervo being the most frequent participant/foils.

Sherlocko the Monk must have been a success from the start, because Mager created 268 episodes over the next 2 years, interspersed with less frequent strips featuring his other Monk characters. Interestingly, even though he employed his cast of characters in the Sherlocko episodes, Mager rarely crossed over Sherlocko into any of the other Monk strips.

The abundance of Sherlocko the Monk strips may also be due to the fact that Mager appears to have developed a deep and abiding enthusiasm for Doyle’s Baker Street boys. Aside from numerous clever in-jokes worked into the comics, some of the episodes clearly reference Doyle’s stories. For example, Mager’s “The Case of the Astonished Assassin” has the same Sherlock Holmes silhouette painted on a window shade that occurs in the Doyle story, “The Adventure of the Empty House.”

Mager’s art on Sherlocko the Monk became more stylized and refined as time went on. By 1912, Sherlocko had become taller and thinner, while Watso became shorter and fatter. Mager’s ability to draw objects and settings grew by leaps and bounds. The humorous effects of the strips increased, as well. After awhile, one of the joys of reading the Sherlocko comics is watching Watso cover his mouth with his banana fingers and exclaim, “Astounding!”

The strip spawned a popular catchphrase, inspired by Sherlock Holmes' cocaine habit: "Quick, Watso, the needle!" Due in large part to the cartoonist/slang-master Thomas A. "TAD" Dorgan using it in his Daffydils daily comic strip, the phrase caught on. It is an exclamation at something outrageous, a Mager version of Charlie Brown's "Good grief!" The catchphrase was also printed on pinback buttons that got wide circulation, judging from how often they come up for auction on Ebay. In his introduction to the 1977 Sherlocko the Monk collection (Sherlocko the Monk 1910-1912, Hyperion Press), Bill Blackbeard (a Holmesian scholar in addition to his work in comics history), notes, that, although it is widely thought Mager took the phrase from Doyle, "no such phrase occurs anywhere in the Holmes stories."

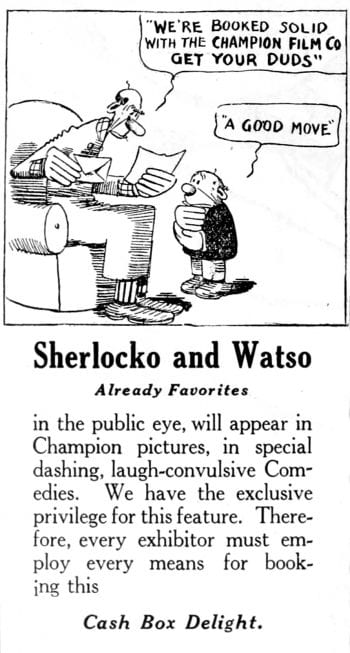

Further proof of Sherlocko the Monk's popularity can be found in this notice, from a December 9, 1911 issue of Billboard:

“Mr. Mark M. Dintenfass obtained on December 1 the exclusive right to produce motion pictures featuring the famous cartoon detective Sherlocko the Monk assisted by Watso. The contract was made and signed December 1 by Gus Mager, originator of the cartoons, and is to run for a period of one year.”

In the year of the contract, it appears that Dintenfass’ Champion Film Company managed to produce two silent half-reel comedies featuring Mager’s characters. The films were not animation, as was the usual case when a comic strip was adapted in to film during this period, but instead live action, with the actors grotesquely made up to resemble Mager’s drawings.

The first film, “The Robbery at the Railroad Station,” was released February 28, 1912. This spirited description from a contemporary film magazine reads very much like a typical episode of the comic:

“Sherlock and Watso, the world-famous detectives are quietly ensconced in their office when suddenly there bursts in on their cogitations a railroad official. He is evidently in great distress, and we soon discover its cause. He has met with a loss – a daring robbery has occurred at his station. It is no less than the loss of his lantern. Giving every assurance to the agitated owner, the keen-minded sleuths set forth on the trail.

An investigation is made at the station with the aid of the magnifying glass in the minutest detail, when finally his most ingenious methods unfold the clue. They follow it up and at last – but hold! Let’s anticipate. Seated at a table, is a man quietly reading by the light of a lantern. This man is Pecko and he it is who has caused the terrible upset in the station agent’s affairs. But why? His answer to Sherlocko is, he wanted to read by a borrowed light. The sleuths, however, recover the ‘glim’ from him, leaving him his bit of candle, with the fair warning to never again tamper with his neighbor’s goods.” (Moving Picture News, Feb.1912)

“The Henpeckos,” a second Sherlocko half-reel silent comedy was released in May, 1912. Shortly after, the Champion Film Company was merged into Universal Studios, and no further Sherlocko films were made, as far as can be determined.

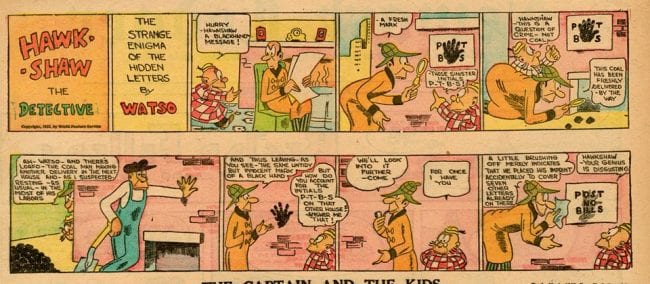

Hawkshaw the Detective (1913-22, 1931-47)

In early 1913, Mager left William Randoph Hearst to work for the publishing magnate’s major rival, Joseph Pulitzer, at the New York World. It is likely no coincidence that Mager's friend and colleague, Rudolph Dirks left Hearst for the World around the same time (creating a rhyming carbon copy of his Katzenjammer Kids called Captain and the Kids).

At the World, Mager created a new version of his Holmes parody, a full color page, that ran in the Sunday supplements from February 22, 1913 to November 12, 1922. In need of a new title, perhaps to avoid one of the many lawsuits being slapped down at the time by the Doyle estate, Mager named his Sherlocko 2.0 character “Hawkshaw,” after a detective character in an 1863 play by English dramatist Tom Taylor. Watso became, less successfully, “The Colonel.”

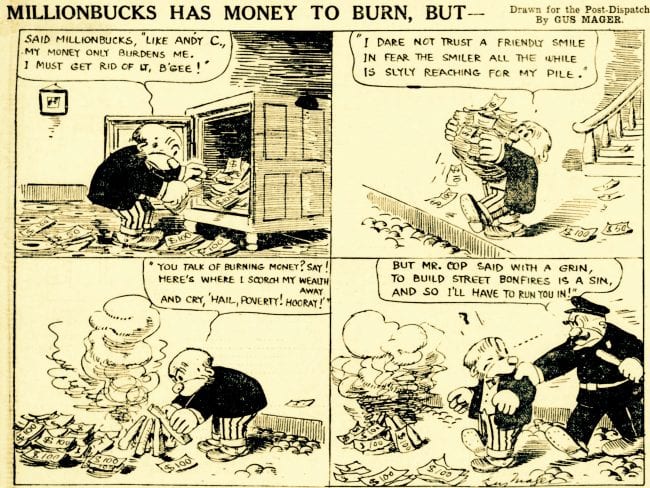

At the same time he launched the Sunday Hawkshaw, Mager began the first of a series of short-lived daily comic strips, Millionbucks, which only lasted from January to June of 1913. In each episode, a fabulously rich character sought ways to get rid of his wealth, only to be comically thwarted. Mager's comics offer many good ideas that later surface in classic comics. In this case, Millionbucks functions as a sort of reverse version of Carl Barks' Uncle Scrooge.

As the Sunday Hawkshaw ended, Mager launched a new Sunday page, Main Street. The first episode appeared October 15, 1922. The strip presented a formerly poor family doing their best to succeed in high society, but perpetually embarrassed by their rustic, backwoods father who was more at home with hobos and the working class. If this concept sounds familiar, it's no wonder.

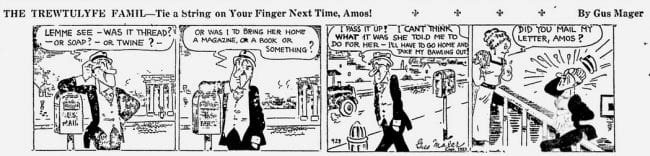

Running in the World, Mager's Main Street is a version of the Hearst-owned Bringing Up Father by George McManus, right down to the art deco stylings. Nonetheless, Mager's considerable cartooning charm lifts the page up beyond a dull copy and offers some lively reading. Consider the over-the-top faux pas depicted in the next-to-last panel of the episode shown above -- an extreme McManus rarely, if ever reached. Perhaps Main Street is intended to be read as a parody of the comics of George McManus (who parodied Winsor McCay's Little Nemo in Slumberland with his Nibsy the Newsboy in Funny Fairyland). If Gus Mager's Main Street was a joke, it appears not to have caught on, lasting for a just under a year and ending on October 7, 1923. It would be Mager's last full page Sunday comic. A daily version, called The Trewtolyfe Family ran around the same time.

In the early 1920s, it appears that Mager briefly flirted with becoming a magazine gag cartoonist, even landing a prohibition cartoon in the famed New Yorker.

In 1924, Mager’s Hawkshaw the Detective ran as a daily strip for about a year, and then in 1931 as a smaller “topper” strip above the long-running Captain and the Kids, penned by Mager’s former employer, good friend and fellow painter, Rudolph Dirks. Mager’s name is nowhere to be found on the strip, which is attributed "by Watso.” This is a rare instance of a topper being drawn by a different artist than the main feature's creator -- which may account for the fact that Mager did not sign these -- the syndicate perhaps wished to convey the impression that Dirks had drawn the Hawkshaw strip. There was a long association between Dirks and Mager, and if one studies Dirks' comics, traces of Mager's style can be discerned here and there.

Finally, Mager’s screwball detective solved his last case in the funny papers on December 21, 1947 when the Hawkshaw topper ended. After years of happy, serene country living, Gus Mager died in 1956, possibly more well-known at that time as a painter than a cartoonist.

Coming Up Next - More Gus Mager

The story told so far is not the complete story of Gus Mager’s career and artistic development. In the next FRAMED! we wind the clock back to 1904 and take a look at what could be called the "lost" Sundays of Gus Mager - three short series that represent fascinating experiments in style and content.

The Comics of Gus Mager - A Comicography

Sundays

And Then Papa Came (9/11/04 to 10/18/04)

What Little Johnny Wanted (9/30/06 to 10/28/06)

Troubles of Pete the Pedlar (11/11/06 to 12/16/06)

Hawkshaw the Detective (1913 to 1922, full)

Main Street (10/15/22 to 10/7/23)

Hawkshaw the Detective (topper, third page - 1931 to 1947)

Weekday Panels and Strips

Jungle Land/ The Jungle Society/ In Jungle Society (4/14/04 to 2/27/06)

[Various names such as Knocko, Braggo, Coldfeeto, etc.] the Monk (4/22/04-3/6/13)

Foxy Reynard (12/6/04 to 12/9/04)

Trouble Bruin (12/16/04 to 12/19/04)

It's Too Bad that Willie Stammers (1/20/05 - 1/28/05)

Everyday Dreams (3/2/05 to 5/29/05)

Cecil in Search of a Job (7/29/05 to 9/27/05)

Oily John the Detective (9/20/05 to 10/10/05)

Louis and Franz (12/23/05 to 1/23/06)

Maybe You Don't Believe It (6/24/07 to 8/14/07)

The Nerve of Some People (1/15/08 to 1/18/08)

What Little Sammy Knows (1/28/08 to 2/4/08)

The Merry Widower (4/20/08 to 5/29/08)

Dogs is Dogs (1/23/09 to 3/3/09)

A Misfit Fable (2/24/09 to 3/19/09) Ain't It? (3/2/09 to 3/1/09)

And Not Only That (3/16/09 to 5/3/10)

O. Heeza Boob (9/21/12 to 1/3/13)

Millionbucks (1/18/13 to 6/3/13)

Obliging Otto (6/21/13 to 8/2/13)

Time-Table Tompkins (12/17/13 to 1/6/14)

The Trewtulyfe Family (1923-24)

Radio the Monk (1/2/24 to 3/29/24)

Sherlocko (1925)

Fifty-Fifty Family (1925, dates unknown)

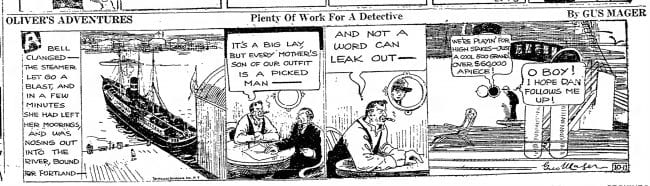

Oliver's Adventures (1926-34)

Un-Natural History (approx. 1935-1940, Popular Science 1-page feature)

Game Gimmicks (approx 1936-1956) Outdoor Life magazine feature

_______________________

Paul Tumey is a writer, artist, and designer who lives in Seattle, Washington. He has run his own presentation design business, Presentation Tree, since 1999. His comics history work appears in The Art of Rube Goldberg (Abrams ComicArts, 2013), which he also co-edited. He also wrote the introduction to The Bungle Family 1930 (IDW, 2014). He contributed an essay to Society is Nix (Sunday Press, 2013), and was also a contributing editor, researching and writing mini-bios of over 50 obscure cartoonists. Most recently, he served as an essayist and associate editor of IDW’s King of the Comics: One Hundred Years of King Features Syndicate. He is currently at work writing a book about the great American screwball cartoonists, which will include Gus Mager.

All contents © 2016 Paul C. Tumey