This interview originally ran in The Comics Journal #117 (September 1987).

Russ Heath may be the least-recognized high-quality artist to ever work in American comic books. He still managed to leave an indelible mark on both Western comics, where he started his comic-book career, and on war comics, for which he would attain his greatest fame. In between he worked just about everywhere on just about everything, from Lev Gleason (on romance comics) to Quality (Plastic Man) to EC (Frontline Combat and Mad) to Playboy (Little Annie Fanny).

The son of a former cowboy, Heath was born in 1926 and did his first comics work in 1942 for Holyoke. In 1946, he moved on to Timely, where his work on Arizona Kid and Kid Colt Outlaw set new standards for realism in Western comics. His longest affiliation was with National (DC Comics), beginning in 1950. There he worked on a wide range of adventure material, most notably Sgt. Rock, which he took over from Joe Kubert in 1966.

At the time of this interview, Heath was working for Marvel Animation Productions, and planning a return to comic books.

KEN JONES: I want to ask you about your childhood.

RUSS HEATH: I was an only child. I think that had a great deal to do with my becoming an artist. A kid has to find something to do if he has no one to play with. I started drawing a lot. I won my first award at 5. It was obvious very early on that I would be an artist, that drawing would be my thing.

JONES: What kind of training did you have?

HEATH: I took lessons at one point for two or three weeks, but, again, I was not a social person because of being an only child, so I dropped out of the lessons. It seemed too much like school to me, anyway. I never really liked being taught.

JONES: How did you approach your first assignment? Were you a fan of the medium, or was it just a job to you?

HEATH: I kind of grew up on Western art and comic books. I read the funnies. My dad bought two newspapers and I read those. Of course, comic strips in those days were about three inches high and I’d pore over them. I even remember how fresh the ink smelled on those things. There wasn’t any television then. There wasn’t much else to do except read the funnies. So, like most people my age, I was really into it. This was even before comic books. When I was 7 years old, my family was down in Florida on vacation and I bought the tenth issue of Famous Funnies. Those were reprints of the Sunday funnies in comic-book form.

JONES: Which newspaper strips inspired you to become a comic artist?

HEATH: Terry and the Pirates, Hal Foster’s Tarzan, Flash Gordon, Scorchy Smith by Noel Sickles, Captain Easy, etc., but I pored over them all. I also did what all kids who were into drawing comics did. I created my own comic books with my name in the title: Russ Comics. Even Hugh Hefner did that. He told me he did one called “Hef.”

JONES: I remember seeing some reprint of some horror work you did for Timely in the ’50s. I saw a vampire thing you drew.

HEATH: I did a lot of horror work for Timely. It’s strange how weird some of that stuff got, but I didn’t notice it at first because it got progressively more bizarre until you had all this rotting flesh falling off ribs. It was all meant in the spirit of fun. They’d give me a cover idea. I used to do funny things on the covers like put a little sign on a coffin that said, “Use no hooks,” or I’d put Kid Colt’s name on one of the gravestones.

JONES: Do you remember anything else about your tenure at Timely that was interesting?

HEATH: There was one thing that happened. When I was at Timely, I didn’t like the idea of penciling and putting tons of black in with the pencil and then having to go back over it with ink. In those days you were either a penciler or an inker and I said, “If I were inking this, I wouldn’t put all this black down in pencil. I’d just ink it.” But nobody listened to me on this point. So I said, “With all this detail in the pencils, why don’t you just shoot from the pencils?” So they shot some test samples of just pencils and my pencils worked fine that way. So suddenly it occurred erroneously to them that they could do without inkers, so whammo! They fired 40 inkers. Of course, nobody’s going to sit there and pencil as thoroughly as I had, so ultimately it ended up a disaster! It was a fiasco that never could have worked, but I was really on the list of a lot of inkers for a couple of years there. I was even less popular with the management because it didn’t work. The only thing that came out of all of it was I started inking my own pencils, but it broke down the system. I remember Stan Lee saying, “I really don’t like firing people. It’s not a pleasant thing to do, therefore I am going to have everything freelanced from now on.” Stan never did hire those 40 inkers back on staff again. I think this is a little-known bit of comic book history.

JONES: What can you remember doing at Timely Comics, the first incarnation of Marvel?

HEATH: I think the first assignment I had from Stan Lee was to pencil the Two-Gun Kid. Don Rico was my editor.

JONES: Can you chart your career at Timely?

HEATH: The comic business kept falling off. It had its peaks and valleys, but the business hit a valley around 1950, so I went over to St. John and worked with Joe Kubert and Norman Maurer who were putting these 3-D books together. Norman didn’t even need to see my portfolio. So I worked on some of the 3-D Tor books that Joe did. That whole 3-D thing turned into a fiasco because all the publishers, big and little, jumped on the bandwagon! There wasn’t enough of the colored cellophane available. So they started trying to dye the cellophane. Everybody got greedy and jumped on the bandwagon and it all went down the tube. Had 3-D built more slowly, it could have been really big! When they started using inks that didn’t cancel out on the cellophane colors properly, it gave everyone a headache and eyestrain.

Then I went over to DC and started doing war stories for Robert Kanigher. I was also working for art agencies and I kind of kept both things going at the same time. I learned early not to put all of my eggs in one basket. I’ve found that if somebody gets you under their heel, they grind it in. Even the nicest people seem to do that.

JONES: What were some of the war strips you worked on? Sgt. Rock is especially memorable.

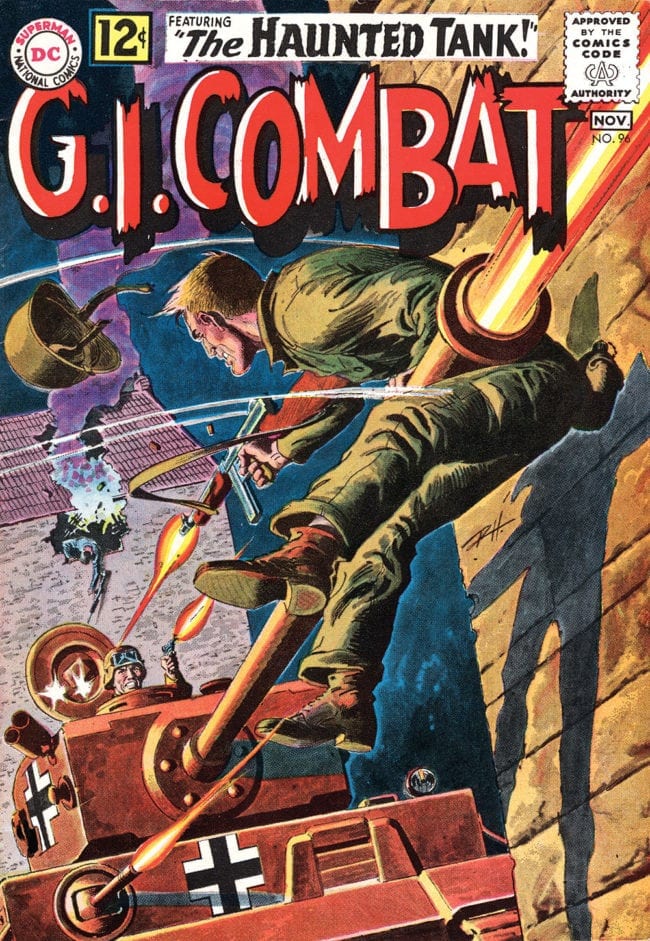

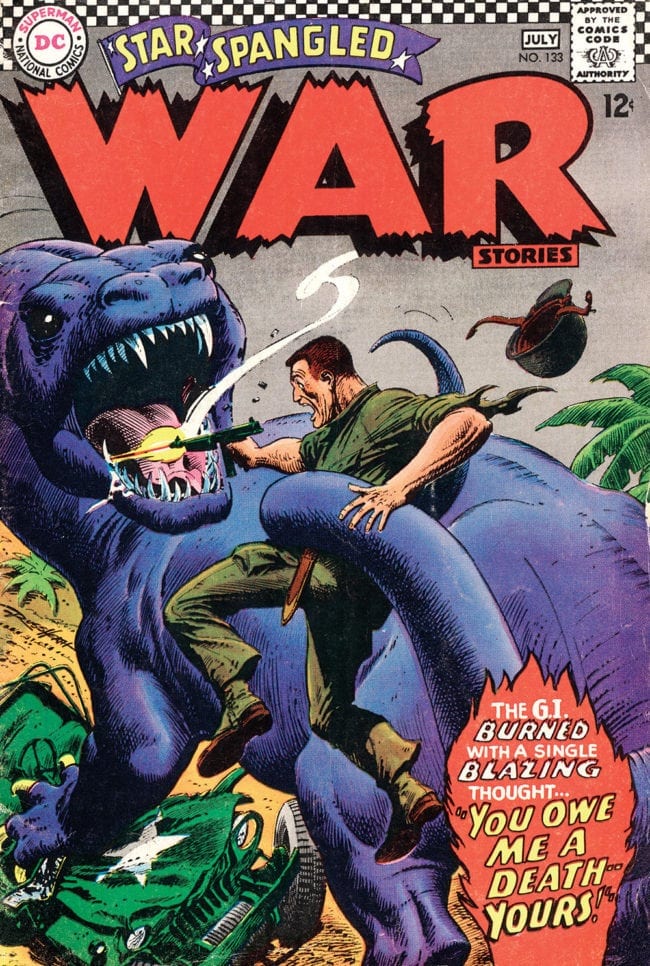

HEATH: Well, I did a lot of war stories besides Rock — The Haunted Tank, G.I.s versus dinosaurs, etc.

JONES: Didn’t you do some unusual covers for DC at the time?

HEATH: Well, they wanted to try to put gray tones into the covers. They felt that if we did that it would give shading. But if you put a gray tone and a color together you get mud, and most of it was pretty unsuccessful. You have to try to do new things, but the thing to do would have been to do a piece of full-color art rather than putting color on top because you get a moire pattern, and then you get mud. But some people were impressed by that experiment. I know they did quite a bit of war stuff like that. I did a number of Sgt. Rock and Sea Devils covers that way. I did about the first eight Sea Devils books plus the covers, then someone else took over.

JONES: Was Sea Devils a fun book to do?

HEATH: It was, except I felt that there were too many characters. It was like Terry and the Pirates. Their old guy was like Pat Ryan, then they had the girl, the big guy and the kid, and the more people you have in a strip, the less reader identification there is with any of them. Like in Terry, Caniff would have Terry go off on an adventure, and Pat was somewhere else, and then they’d meet up later for an adventure. You can’t have two heroes in a story. It just waters the whole thing down and makes it hard to draw. You’ve got four people to draw in every panel.

JONES: I remember some really nice frogmen and submarine war stories that you did, too.

HEATH: Over the years, I never made the money that some of the others did. A lot of people in the industry knock the work out with the dollar as their only goal. You know, “It’s only comics.” I thought, “If I become a hack, will I still be able to do anything good?” So I always tried to improve my technique. It cost me a lot of money because that attitude slowed me down, but that’s my temperament.

JONES: Let’s talk about the “G.I.s versus dinosaurs” work that you did.

HEATH: It’s strange — people seem to have liked those a great deal but I don’t think I did many of them. I doubt that I did more than six dinosaur war stories. Apparently they were very popular. Let’s talk about Robin Hood. Back around the time of the Golden Gladiator, I did Robin Hood.

JONES: That’s right, all those great series in The Brave and the Bold.

HEATH: Also Silent Knight. I’ve done a ton of stuff. Sometimes I forget some old piece and then someone shows it to me and there’s my signature on it!

JONES: If we’re talking obscure then let’s mention the chapter you penciled several years ago in a Wonder Woman Special.

HEATH: Oh lord, that was probably the rarest of all. All those Amazon women!

JONES: Let’s talk about some of the other creators in the DC war line. Can you give us your impression of Robert Kanigher?

HEATH: Kanigher was very intense. I think he drew the best out in a lot of people. He wasn’t the easiest person to work with. I think that, with a lot of people, he tried to find a weakness and exploit it, because then he could maneuver that person better. I don’t mean that statement as saying something negative about Bob; we all manipulate. When you give a girl flowers, you’re manipulating her. One time Bob said, “We’ve got Indians dancing around the campfire here, and you’re not feeling it. I want you to dance around in the office here.” To some people this was demeaning, but I guess from his point of view he was trying to get you to feel what he wanted for the story. He was sincere when he did this, but it did not always sit well.

JONES: Tell us about working with Joe Kubert at DC; you inked some Kubert pencils, didn’t you?

HEATH: Yes, I did, but it didn’t work too well. He’s the only guy to ink his stuff. He’s so brilliant and simplistic. By contrast my inking is highly detailed finished execution. My execution is “all there.” Nobody else should ink Joe. I used to kid him a lot. I’d say, “Come on, you did this cover in 20 minutes, right?” Because it was so great. I have the greatest respect for Joe. He’s really a great guy.

JONES: Besides Sea Devils, The Brave and the Bold, and the war work, what else did you do at DC?

HEATH: We haven’t talked about The Haunted Tank. I did reams of work on that feature. I did Sgt. Rock and Tank at the same time. I just did Sgt. Rock by mail. Joe Kubert was my editor; he took over editing Rock from Kanigher. He’d edit Bob’s scripts and send them out to me. I remember some of the horrendous stories I’d come up with for being late. I found that it was always good to have the stories be at least half true. Nobody ever buys a complete fabrication. Joe did a short story where he was at his house late at night, and he is saying, “Let’s call Russ Heath in Chicago,” and he’s got me saying, “I haven’t had any sleep in three days,” and he showed me with a bunch of girls at the Playboy Mansion.

JONES: You were involved in the early days at Mad. What sticks in your mind about your work there?

HEATH: I didn’t do that much. I did one job called “Plastic Sam.”

JONES: A parody of Jack Cole’s Plastic Man.

HEATH: I did a thing in the Spring issue — it had a big bedspring on the cover — and I had an imitation “Petty Girl” called a “Heathy Girl.” When Harvey left Mad, so did I. When I called Harvey for lunch, he was working at the next magazine, Humbug. I worked on it, too. Later I worked for him on Help!, then Trump, which was something Hefner backed. I did this “Hairless Joe” thing, which was a takeoff on the Breck shampoo ad, although, for some reason, everybody thought that Willie Elder did it. I never signed it because the artist on the Breck ads never signed his work. We were very authentic...

JONES: Besides the Mad work at EC, what did you do?

HEATH: In an early issue of Frontline Combat, I did a story about World War I, which I saw today in a reprint anthology. I got work at EC because of my friendship with Harvey Kurtzman. Every time I called him to have lunch, he gave me a job. I didn’t realize that at the time. If we’d gone to lunch more often I might have been part of the inner circle like Jack Davis and Wally Wood.

JONES: Did you know Wood or Davis or any of the other artists personally?

HEATH: I knew Jack Davis, but not well. I knew John Severin very well. He’s a godfather to one of my kids. I knew Willie Elder. Wally Wood I never really knew. I think I only met him three times.

JONES: When you worked with Kurtzman, did he give you layouts to work from as he did with the other artists?

HEATH: He gave me what you’d call roughs. They were drawings in stick-figure form. Harvey had the ability to get the very best work out of an artist. I believe everybody did their best work at EC. [The EC artists] might do better illustrations now but that was the height of their comic work.

JONES: It was classic material, without a doubt.

HEATH: But there was a lot of money put into the books. They did a piece about a seaplane where they went out to a naval base and even took a ride in the damned thing at government expense. It gave [the EC comics] a lot of authenticity.

JONES: Didn’t you work on Little Annie Fanny?

HEATH: Harvey called me in 1962 at the beginning of the strip. I came in right after the first issue.

JONES: One of my favorite phases of your career was the work you did for the Atlas/Seaboard Company. What can you tell us about your work there?

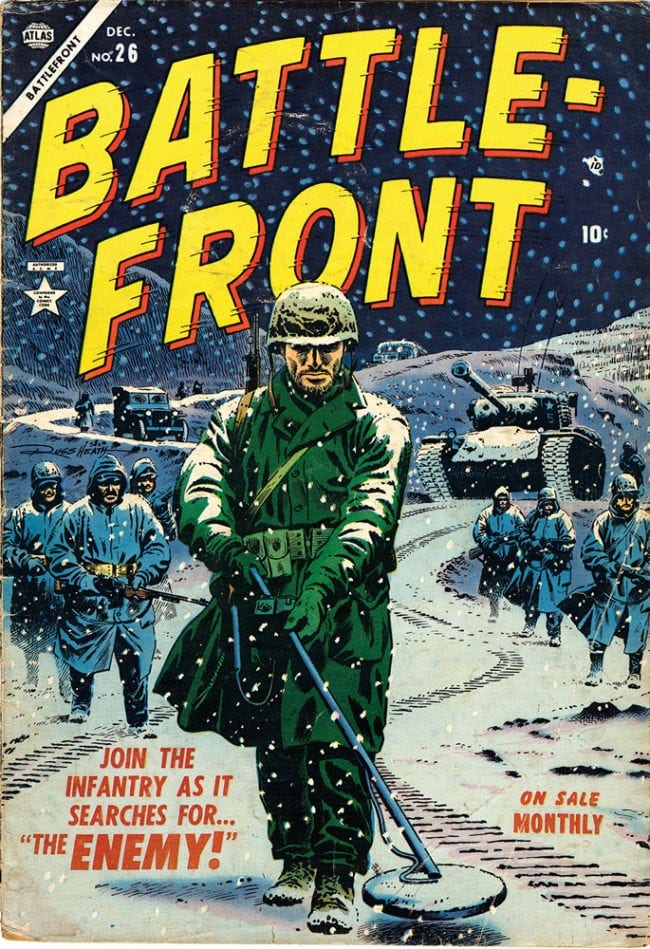

HEATH: I did a war story for them. I was inspired by the fact that they didn’t censor stuff. War is ugly. If you’ve been forced to do war stories, you want to do one that shows war for what it really is. This is the message I wanted to get across to the kids. War is not Sgt. Rock running across the battle ground, bopping people with his fist, and nobody getting hurt. I always wished they’d have in the captions, “Good lives were lost in this battle,” even if they couldn’t show it! Every graduating class in high school should have to look at gruesome films of war so they would learn how unacceptable and obscene war really is.

JONES: I wanted to ask you about another job you did for the Atlas/Seaboard black-and-whites, a story called “Tough Cop” that was just fantastic!

HEATH: Thank you. I was living in Connecticut at the time and drew my neighbor’s car into the strip. That was a story about an old retired policeman that was really unusual. The thing that really made me mad about Atlas/Seaboard was I never got back a really good war story I did for them that they never published. I kept inquiring and was told it had been destroyed.

JONES: You worked for Warren, didn’t you?

HEATH: One time they sent me a script about a werewolf and I sent it back and said, “Why don’t you send me a story about an axe murder? I can relate to that! I’m a realist, I don’t believe in werewolves!” It’s not that I couldn’t do supernatural stuff because I used to do a lot of it. In reference to that Warren type of story, I got to the point where I didn’t want to draw anything that I couldn’t leave lying on the coffee table for my 3-year-old to see. Admittedly, grown-up stories like that were not meant for children, but I had my limitations. Besides, since I don’t believe in werewolves, it’s not scary to me; it’s ludicrous.

But I enjoyed working for Warren even though it cost me dearly in time working for them. Most of the Sgt. Rock stuff only paid $53 a page and the Warren stuff only $110, but then I had to do extra toning on the Warren stuff.

JONES: Have you always been a buff of things military?

HEATH: I think the fact that World War II was going on when I was a teenager influenced me very much. I noticed all the military hardware with an artist’s eye. I can still draw all the bombers, and planes, and small arms of most of the major powers’ Armed Forces. It’s just my “thing.” But then again, during World War II, everybody was very consciously involved with the war. You were either in it or working from the sidelines. Everything back then was either black or white. The Son of Satan story I did was my first and still my only attempt at a fantasy type of story and my first attempt at working from a loose plot — the “Marvel type” of story where the captions and dialogue are written later.

I have long believed that an artist, if not one’s self, should do the coloring on a story. There used to be about three people in the industry who could do color. They had no idea of lighting, receding and advancing colors, highlighting to help separate and clarify, and, most of all, the use of white. I put a great deal of sweat and care into my work and I wanted to do a good job. I told Marvel I would only agree to do the job if they would have me do the coloring. They said OK.

Fearing they would handle the captions and dialogue in the usual Marvel fashion at the time, cutting them out and sprinkling them over the page at random with no concern for leading the eye, I designed the pages carefully, leaving obvious spaces that I assumed they would try to utilize for the captions. Wrong!

It was very difficult for me when I began. What was I to show? All I had was a loose outline. Then it dawned on me; since they had not specified how to handle it, I was free to do anything! Let the writer worry later. I leaned very heavily on research and swipes in this new-to-me type of work. I borrowed from Bruegel, Virgil Finlay, and others I’ve forgotten. I drew all these weird, far-out creatures but they looked somehow comical standing there on a real floor.

If the creatures were unreal, why not the floor? Why not the perspective? Why not break or fool around with all the rules? Foreground smaller, background bigger, forget foreshortening, screw the horizon, verticals, horizontals, drive tent pegs into the sky — and on and on. It was great fun. Maybe you’ve seen a picture of a man kissing a beautiful woman who turns into a clinging skeleton, but French kissing one? All the more revolting! I divided a panel into five equal parts and then reversed from positive to negative on each section. I was really excited about the final result. It looked great in black and white; I couldn’t wait to enhance the effects with color. Of course, I was late and Marvel added a page or two in order to meet the deadline. And, of course, I waited in vain for them to call me to color it. It must have been a pretty good job. Neal Adams bought the originals from me.

JONES: Tell us about your work on the Dracula Lives portfolio.

HEATH: That was originally intended as back covers or end pieces. They used them together in the end. First I did Dracula hovering over the proverbial girl. I liked the implied sexuality of their positions so I reversed them for the second one, putting the female on top for a change. I also experimented with the background, dropping ink onto wet areas. I smoothed the washes with pencil as I remember. Very time consuming, but I’ve never used airbrush. It’s a little too mechanical-looking for me — not the look, but the effect. They were fun.

JONES: Your work on Ka-Zar was interesting. What do you remember about those jobs?

HEATH: I did a Ka-Zar color comic which I was fairly satisfied with. The toned black-and-white Ka-Zar was a disaster! It was contracted through Continuity Associates and there was no way I had enough time to finish it. All I know is it was not my fault! The “Crusty Bunkers” all jumped in to try to finish it, but then Marvel repossessed it and I understand they passed brushes out to everyone at Marvel — even secretaries — to finish it. Incredible. I wish I could buy it back to destroy it.

JONES: Let’s talk about your National Lampoon work.

HEATH: [Art Director] Michael Gross gave me a lot of great stuff to work on. I did some of my very best work for National Lampoon.

JONES: “Cowgirls at War” was one of your best pieces.

HEATH: That was strange. That brought me into areas I hadn’t explored: bondage. I went out to one of the dirty book stores to research it properly. I paid the 50 cents to go into the back section. I came home and did this story, and it’s really interesting because everybody assumes when you do a story like “Cowgirls at War,” that it’s really your personal point of view. It’s not at all. It’s what the editor wanted me to draw. When I finished that job, I didn’t know whether to put the research material into my files or burn it! I got letters from across the country from people who were obviously a little dippy, and they wanted to buy the originals and they loved this stuff.

JONES: It brought them out of the woodwork?

HEATH: It sure did, and here I drew it in the spirit of good clean debauchery. [Laughter.]

JONES: Archie Goodwin wrote that you sometimes used scale models in your drawing.

HEATH: I felt that the kids reading the comics would appreciate that added dimension of realism that using models brings. I’d buy model tanks, build them, and then I could see it from all angles when I drew it. I also did it with airplanes. Sometimes I’d hold the tank against the paper and trace onto the sheet as I closed one eye.

JONES: Goodwin also mentioned that your dad was a cowboy.

HEATH: Yeah, he was a cowboy in about 1917. I just took a trip out to Arizona to try and find out where his ranch used to be. I came close but apparently there’s nothing there any more but sand. The ranch was split into several ranches. Mormons bought one, and they have big gates, and you can’t get in there. There’s nothing to see anyway, but I did check the entire territory out. I found the mines he worked in Jerome.

JONES: You’re a veteran, aren’t you?

HEATH: I was in pilot training in the Air Force. I was in basic training when Germany surrendered. When Japan surrendered, I only had nine months’ service, and they let me out. In fact, I came out with so little time, they were about to draft me so I joined the Air Force Reserve, not wanting to end up in the ground forces.

JONES: Were you influenced by classic movies?

HEATH: I’ve always loved movies. Sometimes I’ve seen as many as three movies a day when I was stationed in a place where there was nothing to do but see movies. I think I’ve only walked out of two movies in my life. It takes a pretty bad movie for me to give up on it.

JONES: Which movies have influenced you the most?

HEATH: The good ones.

JONES: Which war movies do you like?

HEATH: There are some excellent war movies. Fixed Bayonets and Steel Helmet were both about the Korean War and were excellent.

JONES: Let’s talk about the Lone Ranger syndicated strip that you did.

HEATH: Well, I always wanted to make it more interesting by having Tonto have an affair or something. It was interesting — we had a sequence where Tonto jumps off a high boulder because somebody’s sneaking up on the Lone Ranger. We see Tonto jumping on what looks like a man, but because this person has a large coat and hat on you don’t realize it’s a woman. In the next panel we see Tonto straddling what turns out to be a woman and the syndicate said, “You can’t show him straddling a woman!” So they altered my art.

I drew it for about two and a half years. Unfortunately the Lone Ranger’s time had passed. The premise is just too old hat. The pay was minimal but I tried it anyway, thinking maybe it would get enough papers to make it pay. The Lone Ranger Television Corp., who owned the rights to The Lone Ranger, felt they should edit it. The person they had as editor didn’t have any experience at plotting strip storylines. It’s quite a science to balance and integrate the Sunday and daily strips so readers can follow along. Some readers only buy the dailies and some only the Sundays.

This editor felt the strip must be kept moving along at a great clip. A storyteller who knows his craft can keep a strip exciting and full of action without advancing the storyline too rapidly for the reader to follow.

Anyway, the strip at its best never had more than 60 papers and not many of the more important ones either. When the owners of the strip and I realized the strip was going nowhere it was dropped. Some people have shown interest in publishing the collection in a book or two. That would be interesting. So few people have ever seen it. Maybe, one of these days...?

JONES: What are the differences between doing a syndicated strip and a comic book?

HEATH: When I started doing The Lone Ranger, Doug Wildey, who did the syndicated strip Ambler, said, “Any illustrated strip is going to fall behind deadlines, and you will call your artist friends and stay up working all night.” He sure as hell was right! After a number of months I called on Doug to help me, and I called on others. On the other hand, the season at Marvel Productions started and I said, “I can’t do the strip and the animation both. I can barely do the strip, but I’ll try to do them both for a week and see what happens.” It was pretty weird. It was like the story I heard about Stan Drake putting his foot in a bucket of ice to keep awake. I started out at 6 a.m. in the morning before work, came back on my lunch hour, and worked on it from 7 till 11 p.m. This was seven days a week. The big advantage on the weekend was I didn’t have to go to the office.

You can’t believe the problems you run into when you work that kind of an 89-hour schedule. Such things as, “How do I get my pants back from the cleaners?” Newspapers are published every day of the year. If you miss your deadline, you get hit with massive fines. The syndicates have to send the stuff off to all the newspapers by Federal Express at $32 a pop, so you can run up $2000 a day in fines. If you’ve never had a syndicated strip you can’t imagine what it entails. It’s just mind-boggling! I had no time left for exercise and I put on 30 pounds. If I’d had to work on The Lone Ranger six months, they’d have buried me. The strip wasn’t in enough papers to make any money. I think The Lone Ranger was just an outdated concept. Newspapers are dying anyway. When I was a kid there were about 50 strips. About two newspapers carried most of them between themselves. Today there are about 2500 strips, and most papers only carry a small fragment of the available strips.

JONES: Do you think it’s possible that comic books and comic strips might both die out?

HEATH: I think the self-contained comedy strips will survive, but who wants adventure continuity strips? If Milton Caniff was a young unknown today, he wouldn’t be able to sell an adventure strip. It’s like this — would you want to watch a television series every night? What if you missed an episode? Everything is so speeded up. A newspaper strip that is collected in a book, such as Noel Sickles’ Scorchy Smith, is really nice.

JONES: How did you wind up at Marvel Animation?

HEATH: Stan Lee moved his operation out here, and Stan and I were old friends so I just dropped in and said, “Hello.” I was not looking for work but Stan said, “Hey Russ, you’ve got to come to work for us.” Well, money talks. I couldn’t say no.

JONES: Which projects have you worked on at Marvel Animation?

HEATH: G.I. Joe, The Hulk, Spider-Man. That’s the funny thing about animation, Ken. I do these drawings that the animators work off of. So there’s no evidence that you’ve done anything.

JONES: You do storyboards, right?

HEATH: I started out doing layouts for Hanna-Barbera, Filmation, Disney, Ruby-Spears, and backgrounds for Ralph Bakshi’s American Pop.

JONES: A lot of comics people have gravitated to animation.

HEATH: That’s true, because comics on the whole don’t pay that well. You’ve got to produce a ton of stuff like a John Buscema does or else you have to do animation and comics to make a good living.

JONES: You’ve worked with writers and you’ve written your own stories; which do you prefer?

HEATH: I can come up with plot ideas, but I am not a writer. I like to plot with the writer. A lot of the comic strips I’ve gotten have the same six clichés. I redo stories my own way, and they don’t argue with what I send in, especially if it’s really late.

JONES: Do you know any of today’s comic books?

HEATH: I mostly see them through the guys at Marvel Animation. Sometimes I go to the comic shops with the guys from work. I don’t remember the names of most of the titles. There are so many comic books out now, how can you keep track of them all?

JONES: What made you decide to re-enter the comic book field?

HEATH: Number one, the money is a lot better than it used to be. That’s if the book sells well. Since I’ve been working almost exclusively in animation since 1978 a lot of new comic readers do not know my work. Going back to the ’70s, when I was doing war books, a lot of readers who read comics would not read them, the Vietnam conflict being so unpopular at the time. When the Shadow book comes out the readers who don’t know my work will say — “Who is this guy, Russ Heath?” And the ones who knew of my stuff will say, “My god, Russ Heath, is he still alive?” I hope working on a book this popular will lead to new recognition in a short time.

JONES: You’re working on the Shadow graphic novel for Marvel. How did you get involved with that?

HEATH: When I finished my work up at Marvel Productions, I called Larry Hama at Marvel comics to see if there was something for me to work on. They didn’t have anyone free to ink the book.

JONES: What do you think about the recent controversy about rating comic books?

HEATH: The controversy I find to be stupid. I think books containing inappropriate material for children should say “adult” on the cover. But this only as a guide to the buyer. After all, what’s wrong with telling the potential buyer what’s in the book?

Parents should be the only ones to control or influence what their children read — the dealer has no business censoring the books — that’s not his job.

JONES: Should there be censorship in comic books?

HEATH: No. Adults should be able to read anything they want. The key word here is “adult.” I know some people who are pretty damn old and may never be “adult.” The only one to censor reading material for children is their parents. Censorship in the industry leads to all kind of problems — pre-censorship being not the least of these. Publishers watering down material for a certain rating even before the reader can make what should be his decision. And the artist, writer, and editor watering the material down so the publisher won’t kick it back again.

JONES: Can you tell us anything about your future plans?

HEATH: Events will probably dictate my future. I have an agent now that I hope may bring in work connected to movies. I feel it’s possible comics and animation, due to economics, may be greatly curtailed. But I think movies will always be made.

Also, I’ve always thought I might want to go into Western art.

JONES: What do you think about the trend in today’s comics toward nothing but superhero properties?

HEATH: I never did superheroes because I didn’t believe in the concept. I am very literal. If Superman jumped over a building and hit the pavement, the pavement would shatter and the feet in Superman’s costume would be gone. You can apply that to all those superheroes. How does Superman see if he is flying through hurricane winds? I have to believe it can happen or I won’t draw it. I did do a few issues of The Human Torch in the ’40s.

JONES: Are you optimistic about the future of comics?

HEATH: I think television has cut heavily into comic books. I can’t imagine someone turning off their favorite show on television to read a comic magazine, but I can very well imagine someone throwing down their favorite comic to watch their favorite television show. After all, television appeals to more senses at the same time. It stimulates the auditory senses. There is also timing involved in motion pictures and television. They feed it to you at a certain rate. When people tell me a book is better than a movie, I can’t believe it because a book only involves a few senses.