THE BOOKSTORE EXPERIMENT

SULLIVAN: The Ghastly Ones was an interesting Goreyesque volume. How did that come about?

SALA: It was an homage not only to Edward Gorey but also to William Steig, the cartoonist, who’s a huge hero of mine. The Ghastly Ones is based on his book The Lonely Ones. I just always wanted to do a book in that tradition. I did have to re-read everything Gorey had written so that I wouldn’t duplicate any of his rhymes or names.

SULLIVAN: The publisher was “Manic D Press” — is there really a Manic D Press?

SALA: There really is. They’re a small press publisher, run by Jennifer Joseph, and they publish mainly poetry or political books, and some fiction. They approached me to be in an anthology called Sign of the Times — they were using a lot of Bay Area artists and writers. They used Adrian[Tomine],and I think Mary Fleener, and Keith Knight, and a lot of fiction and poetry. And they got it into bookstores. I saw it in every bookstore I went to.

I said to her at one point, “For a long time I’ve had this fantasy about doing little William Steig or Ronald Searle-type books.” I envisioned doing books that would be in humor sections in bookstores, just waiting for some unsuspecting shopper in the Midwest to discover.

You know, the Humor section is such a ghetto in bookstores. But people are always looking in there. I wanted some anonymous shopper to find the book and be like, “Yeah! This is cool!” When I went to get a mocked-up copy bound, I remember the cute punk girl who worked there saying, “Wow, this is great. Are you going to sell these?” That made me feel I was on the right track.

THE CHUCKLING WHATSIT

SULLIVAN: You did a lot of stuff with Kitchen Sink. When they went on hiatus or whatever happened to them, did you have work that was left with them?

SALA: The last project I talked about with Kitchen was a Mr. Murmur comic. Mr. Murmur is the main character in Thirteen O’CIock, and I thought it would be fun to do a series of his adventures. But I’m the kind of person who needs more stability in my life, and it just looked to me that Fantagraphics was really in it for the long haul. These were guys that — if they weren’t doing comics, they wouldn’t have anything else to do! [laughs]

SULLIVAN: They wouldn’t have candy bars.

SALA: They weren’t interested in making candy bars. I admired Denis’ ability to stay afloat. I’ve got to give him credit for that, but I can’t live like that. I couldn’t live working for six months on a project and turning it in and not knowing if it’s ever going to come out.

SULLIVAN: How did you end up at Fantagraphics?

SALA: I was focusing on The Ghastly Ones and I was really burned out on doing short pieces. Then, Fantagraphics sent out form letters. They said, “We’re starting a new anthology. It’s going to be called Zero Zero and we want to know if you’re interested in doing it.” One of these cattle calls to probably 500 cartoonists. I wrote Kim Thompson back saying, “The only way I’m ever doing another anthology like this is if I can do a long continued piece.” I was shocked, because he got back to me and said, “Yeah, that’s fine, lets do it.”

I started doing The Chuckling Whatsit in the second issue, with the hope of doing it in 12 episodes. I owe Kim Thompson a lot for trusting that I wasn’t going to totally screw up his magazine. I told him I was going to go for maybe 10, maybe 12 episodes. When it went to 17, I think I was beginning to try his patience a bit. But the way I had constructed the story, it had to move at a certain deliberate pace. I envisioned it as a process of peeling the layers from an onion, or slowing peeling off mask after mask, getting closer to the truth.

Sometimes we got issues out every six weeks — it was amazing how fast some of those came out. And still it took me two years of my life to do that. I hope people enjoy it because I was trying to reach for something new.

Like I said, I feel that this is just the beginning, and now I’m finally hitting my stride. See, this is why being an artist is not like being a rock star. When you’re a rock star or a model or something, it’s all over by the time you’re 40. As an artist, you look at Matisse and Picasso, they were still doing work when they were in their 80s. A lot of comic artists, unfortunately, get burned out. Then there’s people like Charles Schulz, who’s still going strong. Chester Gould, my hero, he kept going. Al Capp, another big hero of mine, he just kept going. Robert Crumb keeps getting better.

Now that I’m in my 40s, I’m much more settled down. There’s less turmoil in my life, and I can concentrate on doing the kind of work I want to do. I’ve been very slow hitting my stride, which is why it’s a little embarrassing to talk about all the earlier stuff.

EVIL EYE

SULLIVAN: You told me you thought Evil Eye is some of your best stuff, and now you find it hard to look at earlier stuff, because of what you’ve moved on to. How do you see what you’re doing now as an advance over what you’ve been doing?

SALA: One of the things I was doing in the late ’80s and early ’90s was trying to transport my love of certain types of literature and writing into the comics world.

I was reading all these great hard-boiled writers like Kenneth Fearing, Howard Browne, David Goodis and Paul Cain. I was falling in love with their styles. Even someone like Robert Leslie Bellem, or Jonathan Latimer, who are almost comedians, comic writers — their stuff was just addictive to me. You can see some of their influence, primarily in the use of first person narration.

I’ve always been a reader — everything from Grimm’s fairytales to Flannery O’Connor — and I wanted to be a writer. The result, I think, is that I was over-writing things to some degree. I would edit the writing, but I couldn’t edit past a certain point. Consequently, there wouldn’t be as much room for the art. I was writing things that should have been 200-page stories in five to ten pages. That one in Black Cat Crossing, “The Fellowship of the Creeping Cat,” that was my prototype for The Chuckling Whatsit. It should have been 100 pages, but it was squeezed into eight pages or something.

I think what I discovered with The Chuckling Whatsit — the reason I wanted to have more space — was that I’d be able to tell the story visually. I realized I shouldn’t be coming to comics from literature. The truer antecedent, is — of course — movies. That’s where to learn how to tell a story visually. So now I try to keep the text down to a minimum, and I’m still exploring that.

And you have someone like Seth, who is just really terrific at telling a story visually. He’s really effective at showing how an artist can sustain a mood without any text at all. Of course, I could go on and on about Masereel and Lynd Ward, because they both did those picture novels and were masters of visual story-telling.

SULLIVAN: One of the things that struck me reading the first story in Evil Eye was that it reminded me of the Italian giallo. Both the title, “Reflection in a Glass Scorpion,” which sounds like one of those ’60s murder mystery things, and also there’s very little text, and it’s constructed around fairly graphic murders, like a Dario Argento movie.

SALA: Absolutely. A giallo is an Italian thriller, and Argento is the master of that form. There’s also a counterpart in Germany called the krimi. All these wild and wonderful black and white thrillers based on Edgar Wallace stories from the early ’60s, which were actually a big influence on Argento. Those are both huge influences on me. Giallo is the word for “yellow,” and it comes from the fact that at some point in Italy, their thrillers were printed in a series with yellow covers. Just like in France, it’s roman noir, because all the Jim Thompson and David Goodis stories had black covers.

As for giallos, yes, I’m rediscovering a kinship with my Italian heritage. [laughs] Once again, it’s this duality thing. I have the super-repressed puritanical WASP Mayflower-stock mother side, and then I have my father’s Italian heritage, which is, you know, all sex and violence. So I have this total war with these two sides of myself.

For example, the maternal side of me loves Tintin. It’s more of a sexless world —

SULLIVAN: The clean line —

SALA: Very clean line, very reassuring, very comfortable. But then there’s the other side of me that liked the monster movies, and the Warren magazines. The first ten issues of Creepy and Eerie were incredible to me, those Frazetta covers, so evocative. I was only exposed to EC as a kid from the paperback reprints, which scared the hell out of me as a little kid. The Warren comics were a little bit more palatable.

But — yeah, this is like a thriller, of course The Chuckling Whatsit was, too —like Deep Red, or one of the other genre thrillers. Argento’s not the only guy.

SULLIVAN: There’s Bava …

SALA: I actually hesitated to use the title Evil Eye because that’s the title of an obscure Bava thriller from the early ’60s with John Saxon. But I figured — oh well — it will be an homage to Bava, who did one of my favorite giallos of all time, Blood and Black Lace.

I’ll also have back-up stories in Evil Eye, primarily one called Peculia. It’s a bit of a romance, although anyone who’s read any of the episodes so far may not quite see it that way!

SULLIVAN: “Reflections” is also the story of yours that has the most extreme violence.

SALA: Really?

SULLIVAN: There’s usually not much blood in your stories, yet this has the scene of the nailing of the mask, which is from another Bava thriller, right?

SALA: There’s that classic scene in Black Sunday with Barbara Steele, yeah. As a matter of fact, that really depressed me, because my story was all penciled and everything, and then that stupid Leonardo DiCaprio movie, Man in the Iron Mask, came out and you couldn’t turn on the TV without seeing the mask being pounded onto this guy’s face in the trailer. It’s so frustrating when that happens. Especially if it’s something really mediocre, and you know everybody’s going to think that that’s your point of reference. But anyway, my cartoonist colleagues said I should keep it in, saying, “By the time the comic comes out, maybe no one will remember The Man in the Iron Mask.” But yeah, the mask thing was definitely from Bava, not from Leonardo DiCaprio.

But graphic violence? There’s a little bit of that in Chuckling Whatsit. The violence in earlier pieces was generally off screen. During the ’80s and early ’90s, I went through a phase where I was totally into film noir, where the violence is understated, more psychological. For some reason in the ’90s, I rediscovered the slasher stuff from the ’80s — the cooler stuff. It was almost the stylistic equivalent of punk rock. It was around the same time and anti-intellectual, just stupid, visceral fun. Violence and sudden death are actually very important in thrillers (even post-modern, tongue-in-cheek ones!), because it tells the reader that the stakes are high. Characters have to be sacrificed along the way, like the “sacrificial lambs” that are built into every James Bond film.

And I’ve also gotten so bummed out about the repression in our culture. I’m an apolitical guy, but my one soapbox thing is censorship. I get so outraged by how the religious wackos just hijack our culture and all these moralistic groups that want to suppress everything. I’m an adult. I’m in my 40s. I’ve never hurt anyone and have no plans to. Why do my sensibilities have to be protected? I don’t think violence in movies — or in comics — is any more than one small factor in the development of a violent personality. In fact, I get frustrated when I see a movie where there’s punches being pulled, or a false happy ending. That’s more likely to make me violent. After I see a movie with a false happy ending, I want to go and kill somebody.

CHALK TALK

SULLIVAN: When the tape recorder was off, you were talking about being a minor cartoonist. Can you go into that?

SALA: Well, I was just saying that I’m comfortable with my role as a minor cartoonist. I mean, I don’t feel I’m in the upper echelon of cartoonists. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing.

When I was a kid, I used to dream about the classic artist’s studio where you have a bustling street outside, and you sit at your drawing table all day and listen to music and work on drawings. I have that now. I count my blessings every day.

SULLIVAN: I think one thing that has kept you from being a bigger figure is the fact that you never did a regular book.

SALA: Yeah.

SULLIVAN: But among the alternative cartoonists, you’re one of the more formally superior ones. Along with people like Dan Clowes and Pete Bagge. You are readily identifiable stylistically.

Let’s talk about the art a little bit. At the beginning, you had a primitive style. It reminded me a lot of Lynda Barry. But you progressed to a very fluid line, and a very solid, professional style — some people would say slick.

SALA: Really?!

SULLIVAN: How do you see your art changing as you go along? Are you striving for a certain feel or effect or a facility?

SALA: First of all, I think the one thing that’s been consistent is my identification with expressionistic artwork. Of course, I like other kinds of art, too — everything from the work of old Esquire-type cartoonists like Alajalov and Miguel Covarrubias to Ukiyo-e artists like Utamaro. But in my heart I’m an expressionist, and that separates me from a lot of the other comic artists. I’m not really interested in perspective. I’m not really interested in proportion. I’m interested in psychological states and atmosphere.

You were talking about my earlier work. In some way that’s a product of its time. It’s a “New Wave,” or punk, kind of look. I’ve heard people say Lynda Barry before. I think we have similar influences, particularly the Hairy Who, a group of Chicago artists. She went on to be very uninterested in drawing, as far as I can tell. Although she does that little kid’s voice thing pretty well. There are not many cartoonists interested in drawing in their weekly strips these days. The nadir has got to be Ted Rall. He’s just awful, but of course, he’s a huge success. He’s like a lot of the weekly cartoonists who have no love of drawing in their drawings. I don’t understand it. Weekly strips are worse now than they’re ever been. I have no problem with crude drawings, but in Ted Rall’s stuff, there’s no ability whatsoever. From what I’ve read, I guess he thinks he’s some land of hip, edgy guy. But his style is so middle-brow and new wave and derivative. He’s like the Knack of cartoonists. Of course, I’ve got to say that Matt Groening’s still great. He’s been incredibly consistent over the years.

I think my work is pretty crude. When I look at Dan, or Hergé, or Chaland or especially someone like Al Capp, I want to kill myself.

SULLIVAN: You were talking about looking ratty — I can see it in the early days. I think you moved away from that, but one of the things that sustains that, which is obviously a conscious decision of yours, is to not completely fill your blacks. You do that scratchboard look —

SALA: Yeah. It’s funny when I see people trying to imitate that; I don’t know why anybody would. It's born out of a neurotic, obsessive, almost insane compulsion to just sit there and work. There’s a reason why no one else has ever done something like that, outside of woodblocks or something. It’s because it’s insane. And by the way, I’ve stopped doing it so much myself, as I’m getting more mentally healthy.

I’m amazed that I turned out Chuckling Whatsit so fast working like that. There’d be a whole half a page that would need to be black, and I’d come up with a Rapidograph and start just working on it. I mean, it was insane.

SULLIVAN: That’s how kids draw, but you’re still doing it! [laughs]

SALA: I know. I can’t explain it, I can’t justify it, and I’m certainly not going to defend it. One of the things I learned in art school was to be open to these kinds of accidents when they happen, and just go with them. Sometimes you discover that they’re insane, and you stop doing them, [laughs] and sometimes they turn into stylistic quirks that you keep forever. They’re things that feel right when you’re doing them.

When I was doing some of my early watercolors, I’d start drawing these lines that would electrify my head. I would just become alive, drawing these insane quirky lines, or drawing these faces, these proportions and twisted bodies, and suddenly I felt like, “This is like the greatest feeling in the world.” That’s why I say it’s like an exorcism. I literally felt better. And some of those stylistic quirks, they end up coming into my comics. And it’s not always a good idea to put some of that stuff in the comics.

BIG NOSES

SULLIVAN: One thing that we talked about on the phone was your noses. [laughter] You said that you’d thought about the noses.

SALA: Sure, of course!

SULLIVAN: You do such large noses — but your heroes always have tiny, petite noses.

SALA: Is that right?

SULLIVAN: Well, the cipher blond guys tend to have a little female nose almost, but most of the male characters have big honkers. And that’s where you do all of your hatching — on the faces and the nose. They always look like they’re sunburned or really drunk, like a bunch of W.C. Fields characters.

SALA: Well, “the cipher blond guys” — there you’re talking about half a dozen characters from the short stories. But for the most part, if you look at my work, you’ll see the heroes’ noses are as intense as anyone else’s. Fairly big or twisted “honkers,” as you call them. I can’t believe we’re talking about noses! It probably has something to do with repressed sexuality, right? You could probably write a whole thesis on it.

When I was in school, I used to love this Mexican artist named José Luis Cuevas. He did a lot of cross-hatching. Etching was one of my fortes when I was in undergraduate school, which is where I think my line quality comes from. I’m always trying to recreate these etchings I did when I was an undergraduate, I just love that spidery line quality I could get from it.

But this guy Cuevas was a hero of mine, as was an illustrator named Alan E. Cober, who may have been influenced by Cuevas. Cuevas did these drawings where the figures were cross-hatched all over the faces. I used to do that a lot, and then it got more and more distilled, until it was mainly the nose.

Part of me enjoyed it — the feeling of the phallic nose — so I kept it in the work. Jim Nutt did the same thing, playing with the idea of the nose as a phallus — like: “Okay, we know what it is, let’s have fun with it.”

SULLIVAN: One of the challenges I thought I saw you dealing with in your art, especially through the ’80s, was getting the form to stand out. Because of the style that you chose, with the very angular bodies that weren’t terribly representative. I was looking at the cover of Black Cat Crossing, looking at the patterns you did on this guy’s jacket arm, and they weren’t defining the arm, like typical fold patterns.

SALA: Well, considering that absolutely nothing else on that cover has anything to do with reality or naturalism, I’d say the wrinkles on the guy’s clothes are the least of your worries. Once again, I’m not trying to do life drawing. I wasn’t interested in drawing the folds the way that they would fall. I was interested in the formal aspects of composition. That cover illustration is very carefully composed and painted although I was never very happy with the logo. But I worked very hard on that cover. When I did The Chuckling Whatsit — each page was very specifically composed, never haphazardly. If I had to add or delete more lines from a chapter, I’d rewrite the whole thing, just to make sure the pages would stay the way I’d composed them. You could probably develop a whole crackpot theory that the Renaissance was some kind of fluke — that proportion and perspective are things that we just don’t need as artists. I love folk art and art brut, and I like non-hieratic scale, when things are smaller than they are supposed to be, or bigger than they’re supposed to be. Dick Tracy’s filled with “mistakes” of proportion, but that only makes it more powerful. People who reject something like Dick Tracy because it’s not drawn in a photo-realistic style are just showing their ignorance. When I started doing comics, I just drew. I didn’t even try to go with the conventions of the form. Word balloons, ruled-panel borders, perspective, lettering guides, dynamic anatomy …? I thought, “Who needs any of that stuff?” But since then, of course, I’ve learned that comics have developed with these conventions for a reason. Now instead of fighting with the form, I’ve accepted a lot of these conventions and I’m actually enjoying implementing them in my work. But I think the process of trying to find my own way is a healthy one, ultimately.

I just want to tell a good story now.

SULLIVAN: What materials do you use? Are you using a brush?

SALA: No.

SULLIVAN: Have you ever used a brush?

SALA: I’ve tried brushes. Of course, for coloring my work, I use brushes. But, the reason I use the pen for drawing goes back to what I was saying about doing etchings. What I liked about etchings was this feeling that you were making incisions, you were putting pressure down, and feeling resistance, making these sinuous lines. I love that feeling. I lose that with a brush. Many cartoonists have told me that I should try it, but I’m not really interested. I’d miss that feeling. Some of my favorite artists of all time just used pens.

SULLIVAN: What kind of pens do you use?

SALA: Crow quills. Hunt 102,107,108.

SULLIVAN: Are those fine points?

SALA: They’re fine, and they have a bit of a flexible nib. I do use a brush to fill in blacks.

SULLIVAN: Your color schemes are very distinctive. I think of your golden brown tones.

SALA: I learned how to do that from reading about the children’s book illustrator Arthur Rackham when I was in art school. It’s an ochre underpainting. I don’t always do it. It depends what effect you’re after. If you want something a little bit lighter or more vibrant, you don’t need to do it. Sometimes, I’ll do a light gray or a lightblue, and then paint on top of that, and sometimes I’ll just paint layers and layers and layers. Let me show you the back cover for Evil Eye #1.

SULLIVAN: Now the color that’s closest to the underpainting is the ground color here?

SALA: Yeah. You can see this ochre underpainting, then I’ve painted over several layers. For example, you get this kind of gray from painting a red then painting a blue over it.

SULLIVAN: The underpainting is lending a consistency to the whole picture, in terms of the color.

SALA: Exactly.

SKEWING TOO OLD

SULLIVAN: You did a strip for Nickelodeon for awhile. What happened to that?

SALA: I loved doing those strips. I did eight or nine of those “Mervin the Magnificent” stories for Nickelodeon magazine. They were color comics about a magician who was an ego-maniac and a bit of a buffoon — and his much-smarter talking rabbit sidekick (my first and only funny animal character). The strips were a real departure for me, in a way, and I really dug doing them. And there were some other cool artists there, like Kim Deitch. Then I got a call one day. They said, “We’re putting ‘Mervin’ on hiatus.” They had done a reader survey with a focus group of kids. My strip didn’t rate that highly with eight- to 10-year-olds, although it did very well with 11-year-olds. However, the demographics of Nickelodeon magazine, as it turns out, are specifically eight- to 10-year-olds, and that was that.

I guess they’re serious about these demographics. Apparently, I was writing at an 11-year-old level and I was told that either I’d have to simplify it or do something completely new. The ironic part about it is, I wasn’t really writing for kids at all. I was writing it for myself, writing what I would have enjoyed as a kid. But I didn’t know how to make it simpler, so I never submitted anything. Several times I’ve thought about submitting something new, but I’ve never gotten around to it.

Anyway, someday maybe someone will remember reading these goofy strips about a magician when they were a kid and maybe I’ll be in a retirement home and the kid will be a multimedia mogul and will say, “Here’s a million dollars because I loved this as a kid, and I want to buy the rights to it.”

SULLIVAN: So you’ve got to go out and find a magazine that primarily appeals to 11-year-olds.

SALA: I guess so.

SULLIVAN: Like Zero Zero. [laughs]

MORE POP CULTURE

SULLIVAN: Dan Clowes told me that on the one hand you are the ultimate American pop culture junkie, and the other hand you are hypercritical of American pop culture. He said you’ll be ranking on, say, the new Godzilla movie, and Dan will wonder when it’s coming out and you’ll say, “May 20.” You’ll know the exact date. Is that right?

SALA: Sometimes.

SULLIVAN: How does that work? Is there a side that you love and a side that you hate?

SALA: Well, there’s certainly more to hate. I get really angry when, for example, I go to repertory theaters and watch old movies, and people laugh at them. It’s a cross that you have to bear if you love old movies, and sometimes I laugh along with them. But sometimes it just gets annoying, because a lot of times in these college towns like Berkeley, people think they have to laugh. There’s a lot of forced laughter, laughing too loud. Dan will definitely tell you that’s one of my main pet peeves. I just hate that whole Mystery Science Theatre “Let’s mock things that are old and bad” attitude. I know, a lot of people think that they’re cooler than the movies, but you know what? They’re not. Sure I know lots of old movies look dated and creaky and sure I’ve chuckled at that myself, but I can appreciate the honest labor and craftsmanship that goes into making something.

When I was in college, George Pal came to speak at a film retrospective at ASU. He was going to show War of the Worlds first, and then he was going to come on and speak a little bit, and then show The Time Machine. And that audience of Arizona jocks laughed from the first frame of War of the Worlds — we’re talking back in the ’70s now. They laughed throughout the entire movie. Like, raucously laughed. I’m sure there was dope smoking —

SULLIVAN: Of course, it was Arizona.

SALA: Of course. And I’m sure people were out there having a good time, but for Chrissake, George Pal was there. And he had to get up on stage afterwards and say, “Well, I guess it hasn’t aged very well.” I felt so horrible for this guy. Then they showed The Time Machine, and people didn’t really laugh, because it didn’t have the same sort of deliriousness. I guess that’s what gets people, when things go really over the top, and get campy. Then of course when George Pal made his Doc Savage movie, he made it very campy, so that people would laugh with him and not at him. But I guess George Pal couldn’t do camp because that’s a truly terrible and depressing movie.

What gets me is that people are so misguided. They’re laughing at old movies that they consider kitsch. Then they celebrate stuff that is truly kitsch. What could be more kitsch than Forrest Gump? That’s just laughable claptrap. And so is virtually anything with Kevin Costner or Nicolas Cage — guys who take themselves so seriously it hurts! Leaving Las Vegas was more painfully kitsch than any movie Douglas Sirk ever made. Though God knows I have no right to judge. I’m just a minor artist on a minor soapbox.

I love popular culture but I bemoan the whole Siskel and Ebert-ization of America. I’m old enough to remember where going to movies wasn’t a thumbs-up/thumbs-down thing. Every guy in America is suddenly a movie critic. You’re standing in line at a movie, and they’re pontificating about the movie, and it’s — now I’m really rambling. You have to stop me, Darcy. You have to control these ramblings.

SULLIVAN: Well, I was going to add fuel to the fire, because it reminds me of Godzilla. They’ll talk about the original Godzilla and say, “Look at the cheesiness of the special effects,” and yet everybody who’s seen the new one says it’s awful. No matter how popular this movie is — I don’t care if it’s Titanic — it will never have the impact of the original cheeseball cheapo Godzilla, which had an impact that’s been felt for 40 years. It obviously struck some chord.

SALA: People are so afraid of being uncool. They’re afraid that those idiots on Mystery Science Theater or some college students are going to laugh at them. There’s too many smart asses and not enough really smart people. You’re afraid to say, “Well, I like the old Godzilla” because then those people on Entertainment Tonight are laughing at you. As if these idiots are anything to aspire to be. They’re people reading a teleprompter. And yet, in their smarminess, they’re saying to you, “This old Godzilla really sucked, but this new one you’re going to really like, because we spent this much money on it.”

SULLIVAN: What people pick up on now is that the special effects always seemed to be of a different piece than the rest of the film. As compared to now, where once you reduce everything to pixels, the whole thing is a big wash, and you can’t tell where the CGI ended and something else began. But you know, speaking as a complete old fogey of your generation, I have to say that’s part of what attracted me as a child — it drove home the oddness of whatever you were watching, because it was so clearly not in your world. It stuck out, and that juxtaposition was jarring both to the eye and to the mind.

SALA: You’re making a good point, because often the heroes and heroines were really bland, so when the special effects came in, you’re like, “Oh!” Like those Ray Harryhausen movies. I don’t care how many computer-animated things they do, they’ll never compete with those cool Ray Harryhausen movies. I saw Mars Attacks!, and it was such a depressing experience. I’ve had respect for Tim Burton before, but it was as if he’d taken a cherished memory from my childhood — taken this stack of cards that for years were the epitome of pop culture cool, that guys like Norman Saunders and Wally Wood toiled on, took this stack of beloved cards, and just urinated on them until they were a pulp of just nothing — just wet urinated card stock. [Sullivan laughs] I can laugh at silly old-fashioned things as much as anybody else, but man, how wrong-headed can you get?

That’s what I mean about how people can’t do black comedy anymore. I’m sure Tim Burton thought, “I’m doing a black comedy.” But it was just stupid. It wasn’t even on the level of a Bowery Boys movie.

SULLIVAN: I don’t think he has a sense of humor. I think he looks at things that are supposed to be funny and thinks, “Well, I’m not laughing, but I guess that’s comedy, so …”

SALA: I’ve admired some of the things he’s done, but I don’t know what to think. I mean, I’m not anyone to talk. I’m just some minor cartoonist and he’s Tim Burton. But when something like that has so much promise, and they blow it so badly, and it’s so full of Hollywood greed with people like Jack Nicholson, and all this inappropriate bullshit, it’s depressing. Hollywood has been ruining so much cool pop culture lately. And, of course, if you tell people you love The Shadow, Dick Tracy or The Phantom, or whatever, they think you’re talking about the rotten Hollywood version. That’s the point of reference for most people.

They have a vague idea that it’s based on some old pulp, or comic, or something, but they’re only interested in the new version, because they assume if it’s modern, it just must be cooler. I’m convinced that if I live long enough, I’ll see everything I loved as a kid degraded or destroyed by Hollywood. They’re making really good progress on that.

SIGN IN PLEASE

SULLIVAN: While we’re talking about popular culture, Dan also told me that you had an amazing collection of autographs.

SALA: [laughs] Damn!

SULLIVAN: Thank you, Dan Clowes.

SALA: Yeah, well, so?

SULLIVAN: Is this something you did as child?

SALA: Dan’s in Europe right now, so I can’t call him up and scream at him. He’s one of the very first people I was confident to show these to. I know that he, like me, is a pop culture junkie, and he likes the real trashy ephemera of pop culture, the stuff that nobody else gives a fuck about. He’d written about Garfield Goose, the puppet from Chicago, in one of his Eightballs, and when he was doing a signing here in Berkeley, right before he moved out here, I introduced myself to him and showed him some photographs that, as a kid, I took off the TV of Garfield Goose. I think his friend Charles Schneider was there, too, and they were going, “This is like seeing a picture of the Holy Grail.” They couldn’t believe it. Not only the fact that I was that obsessive of a kid that I had saved these pictures all these years, but that I’d actually taken photos off of the TV. I literally had never shown or even mentioned those Garfield Goose pictures to anybody else in my entire life. So I began mentioning other embarrassing things to him.

SULLIVAN: Like the autographs.

SALA: Yeah. That started when I lived in Arizona and I was feeling really isolated. When we very first moved out there, all the kids had swimming pools. Well, I was from Chicago. I didn’t know how to swim. I didn’t know anything about water — we went up to Lake Michigan to feed the ducks, that was about it. So I had nothing to do during the summer. It was too hot to go out, everybody was inside being air-conditioned.

So I would pass the time writing to Captain Company, sending for things. My mom used to buy movie magazines, movie-star magazines. These are things that don’t exist anymore, for you kids out there, magazines like Photoplay or Screen Stars. They were fan magazines, and they often would have columns where you could write to your favorite stars, and they’d put in these addresses. I loved getting stuff in the mail. So I decided who the people I liked on TV were, and wrote to them and asked them for pictures. I wasn’t interested in autographs, I just wanted pictures of them. I still collect movie stills, to this day.

The people I wrote to were not exactly the major stars of the day, although I did write to people like Lee Marvin and Vincent Price. Most of them were these obscure character actors, which is what I think amused Dan.

SULLIVAN: Like Pat Buttram? People like that?

SALA: Not Pat Buttram, but Frank Cady, who played Mr. Drucker, and some other people from Green Acres. One of the first crushes I had as a kid was on Melody Patterson. She was Wrangler Jane on F Troop. She not only sent me like a picture — for some reason, I have two autographed pictures from her — but I have a really nice letter she wrote. She must have taken pity on me. Looking back, I think she was just a teenager herself at the time!

I have letters from people from Laugh-In, and from Lost in Space —

SULLIVAN: Who’d you get from Laugh-In?

SALA: Henry Gibson, Arte Johnson, Judy Carne. But what amused Dan was that I had all these really wacky characters, like Billy De Wolfe and Roger C. Carmel. I always loved character actors. I loved the people in the background, the second bananas. That’s why I always totally related to Drew Friedman’s stuff.

SULLIVAN: Jack Elam?

SALA: Jack Elam, I wish. No, he wasn’t in any TV show that I can remember as a regular, so I don’t have him.

SULLIVAN: He was in some Western. I can’t remember what it was.

SALA: I wasn’t a huge Western fan, but I have Stuart Whitman, who was in Cimarron Strip. Who else do I have? Dan loved my signed photo of Jack Webb and Harry Morgan from Dragnet. I’ve got people from Land of the Giants, Girl from U.N.C.L.E., Get Smart, guys from Rat Patrol, like Christopher George, and Roy Thinnes from The Invaders. Almost every show that was popular with kids between 1966 and 1967, I have autographs. Some shows — like Wild, Wild West or Bewitched — would send these nice color postcards. I still have them. I hadn’t looked at them for years, and Dan was one of the very first people I showed them to, because I knew he’d appreciate the absurdity of this lonely kid like writing to Mr. Drucker, and then Mr. Drucker writing me back with, “Hi, Richard!”

SULLIVAN: How did you pick Mr. Drucker out of the Green Acres cast — was it because his address was in the magazine?

SALA: You know, I haven’t got a clue. Some of the more interesting ones I wrote to included The Avengers. I got letters back from England.

SULLIVAN: How did you get international stamps in Arizona?

SALA: Actually the studio must have forwarded them to England. Those were more charitable times. What else? Dark Shadows — I must have been one of the first people to write to Dark Shadows, because I got back snapshots, taken in the street, of one of the actors. I think they were shocked that somebody would write.

That was a phase I went through when I was a lonely kid — once I started meeting girls, it was all over.

PARENTAL APPROVAL

SULLIVAN: Did your mom and dad care about all this stuff that you were into? Because just from personal experience, also growing up in Arizona, I know my dad was very disappointed that any son of his would like this stuff so much. One of the worst days of his life was one day when we were playing Batman and I put on this neighbor girl’s ballet tights. As soon as my dad saw me, I knew I was a complete total pervert in disgrace.

SALA: It’s amazing that you didn’t go into the military immediately. I can imagine the look your dad must have given you.

Actually my dad was the catalyst for me being into monsters. When Famous Monsters was coming out, he knew all about the movies — he’d seen them all when they first came out. He’d go, “Oh yeah, King Kong, I saw that in the theater when it came out. Phantom of the Opera, I saw that.” Dr. X, Mystery of the Wax Museum, all these movies that became my favorites, he’d seen them all. We had this workshop in the basement, and he would tape up these pictures that I had torn out of Famous Monsters. They reminded him of his childhood, I guess. That’s what made it okay for me to like monsters.

I think the only superhero I ever dressed up as was Zorro. I still love that domino mask. Some of my characters wear that. I can still smell that little weird Zorro mask. I did that little cork mustache.

I was much more interested in monsters. On Halloween, I always wanted to be monsters, or devils, or skeletons.

SULLIVAN: My dad would always try to talk us out of wanting to go to the monster movies. I remember when The Devil’s Rain came out, he was like, “C’mon you guys, there’s all these other movies playing,” and no, we wanted to see The Devil’s Rain. So he dropped us off. He comes back an hour and a half later, and says, “How was it?” “0h, it was okay.” “See, I told you! Next time maybe you’ll think differently.” Next time it would be exactly the same.

SALA: I remember one time like that. My brother and I wanted to go see one of these stupid Arizona double bills: Support Your Local Sheriff with James Garner, which is a Western comedy, and Yellow Submarine, the Beatles movie. We begged my dad, “We want to see Yellow Submarine.” So the three of us go. My sort of macho dad, and me and my brother, these two little wimps. We sit through Support Your Local Sheriff. It’s okay. I mean, it had Walter Brennan in it. It’s all right. And then Yellow Submarine comes on. My dad’s sitting there watching it with us for awhile, and suddenly he leans over to me and says, “How long is this going on?” “Well, it’s a movie.” He was like, “This is going to go on for more than an hour? I can’t bear it.” He thought it was going to be a five minute cartoon. He went and sat in the lobby, and waited for the movie to end. Talk about feeling guilt. We had to come up to the lobby after the movie was over. There’s my dad, sitting there, glowering: “Okay, you saw your stupid Beatles movie.”

I always remembered that, because when that movie Toy Story came out, I wouldn’t go see it. I saw the trailer, all in computer animation. It literally made me nauseous — I felt kind of drugged when I was watching it. I suddenly felt sympathy for my dad. I knew what he must have felt like about Yellow Submarine.

THREE AMIGOS

SULLIVAN: You get together with Dan Clowes and Adrian Tomine often. Do you talk about other artists’ work, or — ?

SALA: Oh God, yeah, but nothing that’s printable.

SULLIVAN: Is there anybody right now who you feel is really on top of their game?

SALA: I’ve got to mention Archer Prewitt, because I just love the way he draws. There’s a piece of his in the last Blab! of a hobo in an alley that’s some of the best drawing I can remember seeing in years.

I think Jaime Hernandez is one of the best cartoonists ever. I think Dan is at the top of his form. Dan is a natural. He was born to do what he’s doing. It encourages me to see him and Adrian because they are really hard workers. They’re very dedicated. Adrian is often lumped in with a lot of other people of his generation, but he’s so much better. I really admire his ability to construct these beautifully written, jewel-like short stories.

Who else? Gilbert Hernandez, of course. Julie Doucet. Christine Shields. People should check out her comic, Blue Hole. She’s really good. But you know for inspiration, I always go back to looking at people like Gahan Wilson, Charles Addams, Jack Cole, all the other favorites I’ve already mentioned. Recently I’ve been tracking down work by this eccentric guy Lee Brown Coye, who did spot illustrations for weird pulps.

SULLIVAN: Is there anybody whose work you just don’t get? Anybody who’s really —

SALA: Everything’s a mystery to me, man. Everything’s a fucking mystery to me. One of the things that got me back into doing comics was how much mediocrity there was. There’s a lot in the illustration world, too. I’m guilty of it myself, sometimes. But Jesus, there’s just so much crap out there, and so much of it gets so lauded. I thought, “Fuck, I’ve held myself back because I didn’t feel I was that good, and this crap is getting attention? Why not me?”

Another minor cartoonist, very minor, some Gen-X type, put out a one-shot comic where he was trying to do an enigmatic kind of story, like “See, anyone can write these dream-like stories.” He had some guy being chased by a parade balloon who suddenly finds himself in his old high school, and there were martians and beatniks, and it was just abominable. Just lame and pointless and proof-positive that the form is not as easy as it seems. You’d think that if someone was going to write a stream-of-consciousness story that some interesting psychological symbols would emerge, even if just by accident. Some grist for the Freudian mill. But there was nothing there. The guy literally had nothing to reveal. We were talking about artists with specific obsessions, and actually this guy is an example of cartoonists who are the opposite, which is much, much worse: artists with absolutely no personal vision, guys that dabble in everything, from post-modern funny animals to “serious” historical pastiches. They’ll try anything. Usually this type of artist ends up as teachers, or critics, or art directors, where they can be in positions of power over real artists.

SULLIVAN: These “jam” mini-comics you and Adrian and Dan do … how did these happen?

SALA: It’s something those guys started in Chicago: Dan, Chris Ware, Gary Leib and Terry LaBan. Another guy that helps us a lot out here is Lloyd Dangle. He’s a terrific, underappreciated talent. I can’t believe that we’re talking about the minis, though, because they’re really just silly. What’s fun is when people like Rick Altergott or Gary Lieb come to town and we rope them into doing the minis with us.

SULLIVAN: You don’t sell these anywhere, I take it.

SALA: Actually, some of them were sold.

SULLIVAN: Oh, really?

SALA: Dan keeps all the ones that are unprintable. He’s got the mother lode. I noticed very early on that when we finished them, there was never a question of who was going to keep them. He always scoops them up. A lot of them are very slanderous. I hope Dan puts instructions in his will to have them burned when he dies.

THE CAREER ILLUSTRATOR

SULLIVAN: Do you make more money at illustrating or comics?

SALA: I don’t make any money in comics. What are you talking about?

SULLIVAN: I thought that’s what you were going to say.

SALA: No, I make my living as an illustrator. What’s puzzling to me, though, is that often in a Comics Journal interview, you see cartoonists saying, “Yeah, I’m working as an illustrator, I’ve got an assignment from Pulse.” Believe me, you can not make a living by selling two or three drawings to Pulse. I’m not always proud of it, but I actually do make a living as an illustrator. It’s not always easy. A lot of it’s degrading and demoralizing, and I’m not even in the upper echelon. I tried to count about a year ago. I’ve done between 700 and 1,000 illustrations since I started in the late ’80s, almost exclusively for magazines.

SULLIVAN: Are a lot of them trade magazines?

SALA: Newsweek, BusinessWeek, Seventeen, Esquire, lots more — lots of newspapers like the New York Times, L.A. Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, etc. Those are some of the good ones, the fun ones.

SULLIVAN: Was it tough to break into those publications?

SALA: I never had to promote myself that hard, because people usually called. The phone rings about twice a week, and that’s enough to keep me going. The only promotion I’ve done is sending out little promo cards. Although the business has really changed in the last couple of years, so new strategies are probably going to be needed.

There are all these competitions that people enter, American Illustration, etc. — I rarely get involved in that. People who know about me know about me, and they hire me, and the people who don’t, don’t. Someone pointed out that I have a success neurosis, which I think is pretty clear, from what I’m saying.

SULLIVAN: You don’t want to be a success?

SALA: I just don’t think huge success is possible, and I’m resigned to that. I’m not that aggressive. I’ve met some of these guys from New York, these illustrator/ cartoonists, and they roll right over me. They’re always on. And I’m not always on. I’m not always looking for a job, I’m not always hustling. I don’t always care who’s working for whom, and that’s usually all illustrators ever want to talk about.

I know I could make a lot more money. For example, ten years ago I was in issues of a now-defunct magazine called New York Woman along with Maurice Vellekoop. Maurice was starting out at the same time, and now his career has gone into the stratosphere. I’m still at about the same level I was then. But he always had a rep. I’ve never had a rep. Some agencies say, “We had the hardest time finding you, why aren’t you in any of the sourcebooks?” Meaning, like RSVP or Showcase.

When I started doing illustration, it was the perfect time for me, because quirky idiosyncratic illustrations were “in.” Now, with computers, things are changing. We’re back to more of a ’70s thing now, where typeface, design and photography are more interesting to people.

SULLIVAN: You used to get a lot of work with Entertainment Weekly. Why aren’t you in there anymore?

SALA: There’s such a revolving door with art directors. They’re always changing. So even though an art director loves you one month, the next month they’re gone, and the new person’s not into you.

SULLIVAN: You never had to go to any of the porno mags to get work?

SALA: I’ve done a lot of work for Playboy. Does that count?

SULLIVAN: Do you ever get assignments where you think, “Why am I doing this?”

SALA: All the time. The nadir was when I had to do dozens of illustrations for a series of Bank of America’s corporate reports. The money was pretty good, but the drawings were painful to do. The subject matter was dumb in the first place, like people pulling bills off money trees, but the client kept making it worse: “Make the people happier, happier! Put more money trees in the background!” I thought, “So this is what selling out feels like. It’s awful.” The art director I worked with sounded depressed himself. Then he’d try to rally and say, “Have fun with it!” I’d hang up the phone and want to kill myself.

SULLIVAN: Why don’t you enter any of the illustration competitions?

SALA: I used to enter when I was younger. I remember being rejected from American Illustration when I sent in what I thought was the best work I’d ever done. I thought, “If they didn’t want that, which was the best I could do, then they’re just not interested in me.” So I rarely even think about entering. I know people who enter every year. It’s a gold mine for whoever owns American Illustration. But I’m not interested. It’s always a small jury of art directors/ designers, and if you’ve worked with them, you’re in. It just seems very inbred. But maybe that’s just paranoia, again. I should give the competitions another try. Or maybe I’d find out that my work simply isn’t good enough for the competitions, that’s always a possibility.

AND FINALLY, NANCY DREW

SULLIVAN: It struck me as odd that you were not with Fantagraphics so long.

SALA: I started with Fantagraphics, but after Prime Cuts, I got soured. No offense to Gary, because I like Gary a lot, but I hated Prime Cuts. There were certain artists in particular that I just loathed. I didn’t have any power to say to Gary, “I’m not going to give you my work unless you stop carrying these other artists’ work.” I just got sick of it. That was another time I gave up comics, and Blab! pulled me back again. Then because Blab! was published by Kitchen Sink, I thought, “Maybe I’ll do a book with them.”

SULLIVAN: How come you never did another issue of Thirteen O’Clock?

SALA: I’d love to do another Mr. Murmur adventure. He may turn up in Evil Eye, but he’s on the back burner for now. I’m concentrating on a character called Judy Drood who is based on childhood memories of Nancy Drew. My brother was really into Nancy Drew books when we were little.

SULLIVAN: Nancy Drew! [laughs]

SALA: He had every Nancy Drew book in hardback that came out in the early ’60s. I’ve never read a Nancy Drew book in my life, but I used to stare at the covers. As with the pulps, I’d feel like, “What the fuck is going on here?” They always had some intriguingly bizarre thing, and it was very ordinary, too — like a girl, a grandfather clock and a staircase, or maybe a music box. But there was a sense of dread. A little shadow around a corner or a branch that looked like a hand. I responded to that. This could happen if you walked outside, or this could happen inside. We had grandfather clocks and things like that, too, and she was just a normal girl, not some kind of supergirl.

I liked the idea of this feisty heroine who’s solving mysteries. I’m going to have a character like that, only she’s a bit more unhinged. She made her first appearance in a story in Black Cat Crossing, and she’ll be a major character in the new series. She’s not in the first issue of Evil Eye. She’ll appear in the second issue.

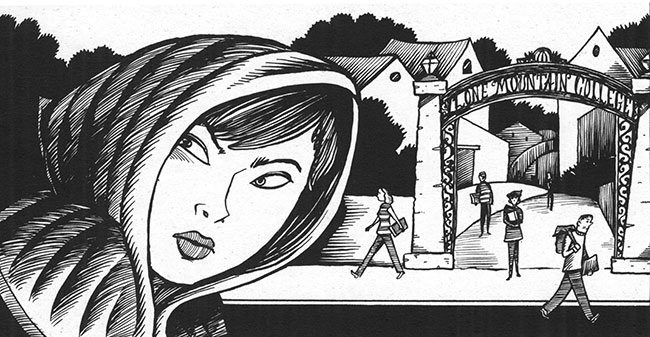

Once again, the story is set in my imaginary take on the San Francisco Bay Area. Most of the action takes place on a college campus. There really is a Lone Mountain College, but it’s nothing like the Lone Mountain College in the story. I took the tower and the entrance to the campus from U.C. Berkeley, right down the street from me. The story involves a group of teachers with a secret, two vicious killers, a band of pirate girls who take orders from a puppet, and the usual hero who’s in way over his head. He’s not sure if Judy Drood will end up helping him or getting him killed. I hope people like it. I started doing comics for myself exclusively, like someone in the world of fine art, but now I’ve really fallen in love with the process and the form of comics. I really feel honored to be part of the tradition.