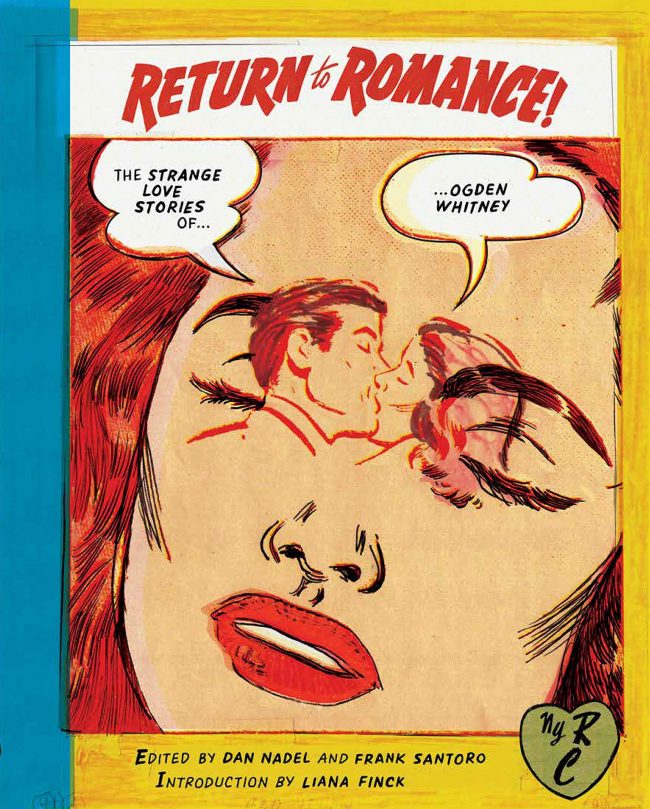

Dan Nadel is one of comics’ most perceptive and adept historians and critics. A former editor of The Comics Journal, he has curated museum and gallery exhibitions, published the art/comics anthology The Ganzfeld, and co-edited Return to Romance! The Strange Love Stories of Ogden Whitney (New York Review Comics, 2019). When I returned to writing for TCJ after a long absence, Nadel influenced me on how I might write about comic art in greater depth. We share an interest in the anthropology of comics—how high and low culture co-exist and the symbiosis of ideas, social influences and biases submerge and emerge in the four-color page.

Dan Nadel is one of comics’ most perceptive and adept historians and critics. A former editor of The Comics Journal, he has curated museum and gallery exhibitions, published the art/comics anthology The Ganzfeld, and co-edited Return to Romance! The Strange Love Stories of Ogden Whitney (New York Review Comics, 2019). When I returned to writing for TCJ after a long absence, Nadel influenced me on how I might write about comic art in greater depth. We share an interest in the anthropology of comics—how high and low culture co-exist and the symbiosis of ideas, social influences and biases submerge and emerge in the four-color page.

When Tucker Stone suggested I interview Dan, I agreed. Our first attempt, conducted on November 5, 2019, was a memorable conversation. We were both in good form, and I remember thinking, in the moment, “this is the best interview I’ve ever done!” I wish I could share it with you today. But due to a forced software update, which started in mid-interview, unbeknownst to me, I lost the recording. (Thank you, Windows 10.) A few days later, Nadel had time for a retake. We discussed the Ogden Whitney book, and a work in progress that is still news to the comics world.

So why is this interview so late in reaching you? My schedule became over-busy for the remainder of 2019 and early 2020, prior to our current pandemic. I never found time to transcribe this conversation. An arrangement to have someone else do this clerical task fell through. In quarantine this April, I got it done.

I usually do my best to have less of myself in an interview, but this became more of a conversation. I’m glad that, against all odds, I’m able to share it with you now.

Frank Young: Your biggest news right now is your announcement that you’re writing a biography of Robert Crumb…

Dan Nadel: Yes, about a year and half ago I wrote to [Crumb] and very matter-of-factly asked if he had given any thought to having someone write his biography, or if he had been approached. He said, “If you’re really serious about it, then come to France, and we’ll talk face to face.” So, Elisa and I flew over. His condition for me doing the book was that I forthrightly discuss the racial and sexual parts of his work and give his critics a voice. It will be a critical biography, not a hagiography. And that’s very much who he is. He’s nothing if not candid and willing to discuss. So, we agreed, and then I worked on a lengthy proposal for about six months, and Scribner bought it in July.

Robert has kept great archives. There’s a lot of correspondence to work from, and he, of course, has had a fascinating life. He passes through big chunks of American culture, from post-War suburbia and trauma to commercial art, the underground press, record collecting and making music, communes, and on and on. In a 1970 interview Jay Lynch called him the Johnny Appleseed of underground comics. Crumb was traveling across the country in the late ‘60s, and in each town, he would meet whoever was publishing the local underground paper, and offer to draw them a cover, or do a strip—kind of jump-starting it in every city he went to. The other thing that’s emerged is that Crumb and few others thought of what they were doing as an art movement. It wasn’t all ad hoc; it was a concerted attempt to create a forum for new kinds of expression in comics. He was very involved in that; very forward-thinking as an artist. In doing so, he tapped into a global zeitgeist, making comics that embodied and critiqued a generational ethos. You have to look at someone like Warhol to find an equal in terms of his implicit understanding of the zeitgeist. And his life beyond the ‘60s and ‘70s is fascinating; his doing environmental work, founding Weirdo, the remarkable comics of the 1980s and 1990s across nearly every genre, and of course Genesis. The quality of the work, the dedication and invention – astonishing.

My task has been locating people, doing lots of interviews and archival work, and trying to lay the foundation for a full portrait of him and his work.

To me, it’s a story about one of the great artists of the post-war era.

I appreciate Crumb’s candor and bluntness about who he is and what he thinks of other people. I’ve been on the receiving end of that a couple of times. And what he said stung, but after I thought about it, I realized he was right…

That forthrightness goes into his work as well. He’s always been the person that notes that the king is stark bare naked…

Even when the king was himself. He doesn’t spare himself. Look, it goes without saying that Crumb is a complicated artist. That needs to be unpacked and discussed. The racial and sexual imagery is a fraught, difficult, and worthy subject. It was meant to be. Closer to TCJ’s home, without Crumb alternative comics—or literary comics, whatever we want to call them—wouldn’t exist. What that means, how his influence may or may not be baked into the medium, is worth exploring. Then there’s his profound impact on American humor, and perhaps even more so, an incalculable influence on contemporary art, from Mike Kelley to Nicole Eisenman. Getting to understand the visual vernacular he was working in, and the history he was sketching out, where he went thematically, formally, and geographically, is pretty important to understanding large swathes of culture today.

In that way, I think he’s furthered American satire and social commentary even from the works of his hero, Harvey Kurtzman.

Yes, it’s on a different level. Kurtzman’s work is incredible, and what Crumb has done is to take that energy and turn it inward. Instead of only satirizing a movie or a TV show, he’s looking at the root cause of the phenomenon as well, and then looking at his own reaction to both the thing itself and what lies underneath it. That level of reflection is unusual. You see that in some literature and art of the time, but very rarely in comics. Moreover, he never got stuck in an era or trapped in a monolithic mode of thinking. He kept pushing.

I’ve heard that Crumb considers himself retired from cartooning now.

Whenever any artist says that, you have to take it with a grain of salt. Because you can never know when somebody with that kind of mind is going to decide to call it quits. At this point, cartooning is not of great interest to him. He’s not driven to do it very much. And after 50 years of pretty relentless output, it does make sense. He’s still writing and drawing; he plays music a lot; there’s still a lot of creativity happening.

No one could fault him for not feeling an obligation to create new comics…

No. He felt an internal obligation for decades. He just couldn’t stop drawing. That compulsion has gone away. He never felt an obligation to an audience, anyway. If he feels that it’s authentic to who he is, he’ll do it. If not, he won’t.

It will be valuable to have the story of his adolescence and young adulthood told in a non-sensational way…

There’s the biographical part, and then there’s all the contexts in which he existed that haven’t really been fleshed out much. What was the world of American Greetings in Cleveland in the ‘60s? Who were the people? What about rural Northern California in the 70s and 80s? The intersection of the counterculture and sexual liberation and commerce? The bands and record collecting; the films; the obscenity busts. And, of course, the underground comics scene and the underground press…all the worlds he’s inhabited have contributed to the work. I want to understand the economics of the underground press in the ‘60s: who got paid and how it got distributed… all that material has to emerge for Crumb to really be understood. People have been very generous with their memories and archives throughout this process.

That’s a part of underground and alternative comics that has not really been told…

Not so much, aside from Patrick Rosenkranz’s (Patrick has been incredibly generous with his own material, I should note) formidable books and Bob Levin’s essays. And I think it’s important. The more we understand about what that was—this incredible boom in underground comics, and then, almost as quickly, its collapse—that’s valuable cultural history. Obviously the counterculture was a big business with a huge audience. What’s interesting is to learn how commonplace it was to read Crumb, or about Crumb, between 1968 and 1975 in nearly every kind of publication. His comics and imagery were ubiquitous. That says a lot about him, but also a lot about the nature of the cultural appetite.

The world of Robert Crumb couldn’t be much further from the world of Ogden Whitney…in our previous interview, we talked about going beyond the traditional canon of who was important in comics and showing different voices that were not outsiders in any way. They were commercially published artists in mass-market publications, yet they managed to have a voice that stands out from most of their peers.

The world of Robert Crumb couldn’t be much further from the world of Ogden Whitney…in our previous interview, we talked about going beyond the traditional canon of who was important in comics and showing different voices that were not outsiders in any way. They were commercially published artists in mass-market publications, yet they managed to have a voice that stands out from most of their peers.

Yes. Looking back at Art Out of Time, which I wrote in 2005, compared to now, the canon is so diffuse that it’s hard to imagine how uptight it was at a certain point. With the Ogden Whitney book (Return to Romance! The Strange Love Stories of Ogden Whitney, co-edited with Frank Santoro, New York Review Comics, 2019), the intention was to show, in a focused way, that there could be this idiosyncratic vision within the style of a craftsman. And I’m supposed to be shilling for it this whole interview, but you started me rattling on about Crumb!

Romance comics have been really ignored until recently. There are so many of them, and many of them commit the fatal sin of being dull.

Absolutely.

The Whitney book reminded me of the romance stories drawn by Dick Briefer. They’re beautifully delineated. I think they’re the tightest work he ever did…he’s trying his hardest to be a tightly controlled, super-slick artist. But he’s too much of an individualist and a stylist, like Ogden Whitney. There’s a Whitney story from 1956 called “Why Can’t I Get a Man?” (published in Confessions of the Lovelorn #76, 12/56). You know that one?

Oh, yeah.

It’s an incredible piece of “mansplaining.” Like some of the stories in Return to Romance, it appears to be written by Richard Hughes.

He wrote the majority of the (American Comics Group) comics. Romance comics, sci-fi, super-heroes… His real name was Leo Rosenbaum, but he changed his name to “Richard Hughes” and was an editor-writer. And when ACG closed, he wrote cereal-box comics and ad copy. Like Ogden Whitney, he was married but never had a child. Almost nothing is known about him, because he never gave an interview…

Whitney and Hughes’ work for ACG seems so happy and contented…

The sense I have is that there was nobody telling them what to do. Hughes was the editor-in-chief of a small shop, and they were just doing what they were gonna do. And a lot of weirdness and irreverence creeps in because they’re just churning it out. There is a certain amount of joy in their comics that you don’t see elsewhere.

The volume of their work would be a recipe for hackwork in most hands. I most often experience, in reading these stories, that whopped-up-the-side-of-the-head feeling when a really out-there concept is tossed in…like Hughes’ invention of “The Unknown”—his cross between heaven and purgatory…

The volume of their work would be a recipe for hackwork in most hands. I most often experience, in reading these stories, that whopped-up-the-side-of-the-head feeling when a really out-there concept is tossed in…like Hughes’ invention of “The Unknown”—his cross between heaven and purgatory…

I’m glad to see that Return to Romance has been getting a positive reaction from people.

Yes, I think it’s a book that will have a nice slow burn as people discover it. It’s found a non-comics audience because of how unusual the material is. And I feel like the text (which includes an introduction by Liana Finck and an afterword by Nadel) offers a way into the work. It was a fun book to work on. It was great to be creative with Frank – and to have access to Bill Boichel and Copacetic Comics (a Pittsburgh, PA store that the authors call “arguably the greatest comic book store in the United States”).

The real fun of these projects is working with people you really love and enjoying just being together and making something. That was a big part of this. I’ve gotten to know Gabe and Lucas at NYRC over the last bunch of years and that’s been a real pleasure. The book was a long time coming – so long that it started at PictureBox. It feels like a humble monument to the conversations that Frank and I have had over the years, to hanging around and looking at stuff together. There’s no reason anyone else has to know or feel that, but that’s what it was for me.

The book has a good vibe. A touch I like is that, after every story, there’s a page of a screaming primary color—it’s a great visual palate cleanser.

The book has a good vibe. A touch I like is that, after every story, there’s a page of a screaming primary color—it’s a great visual palate cleanser.

Frank and I wanted to make sure that the stories were broken up, so that you can take a breath between stories. It gives the reader permission to dip in and out.

What comics have you read recently that you liked?

I am going to amend this because we’re six months later. In November, it was certainly:

Kevin Huizinga’s newest book, The River at Night, is my favorite thing that I’ve read recently. What he was able to convey about time and knowing one mind and trying to know somebody else’s mind is so beautifully made. That book really knocked me out. It’s phenomenal.

It’s such a cliché to talk about “pushing the medium,” but Kevin is forcing the reader to slow down. Something everyone says about comics is that a book takes a year to produce and six minutes to read. Kevin’s figured out a way, using diagrammatical tools as an under-structure, that he can move us backwards and forwards in the narrative. He’s managed to slow things down in a way that’s really pleasurable and reveals more to the reader.

Between that book and Frank Santoro’s Pittsburgh (which is very close to my heart since Frank is such a dear friend) you’ve got two benchmarks by artists of the same generation. They’re taking things a step forward. And Frank’s amping up what people even think of as being possible in cartooning. The book is process-driven in a performative sense: you’re watching this thing come together.

Fast-forward to April: I just devoured Gilbert Hernandez’s Psychodrama Illustrated. It’s a perfect comic book and fetish object and movie on paper. Gilbert is serving his obsessions these days. The finite format, the cover art, the idea of movies within movies with flashbacks, etc. – I enjoy the puzzle and the pay-off. I’m keyed into it. The Yoshiharu Tsuge books have lived up to all their nerd expectations on every level. What strikes me most about the early and late work is how unadorned it is. He telegraphs nothing about “meaning” and just unspools the stories. I’m not sure how to even think about the work. And…. I got a PDF look at the upcoming NYRC Shary Flenniken book, assembled by pal/mentor/collaborator Norman Hathaway, and I think, first, the work is stunningly drawn and written and, second, the whole post-1970 narrative of personal comics-making needs to be adjusted. She is one of the all-time greats.

As for other updates you asked about: Since we spoke I organized, with Laurie Simmons, a massive exhibition called All of Them Witches, which opened February 8th at Jeffrey Deitch in Los Angeles – over 70 artists from 4 or 5 generations. And I recently began work on a summer 2021 exhibition for the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago about the history of comics in Chicago.

You asked about COVID life – look, I feel foolish saying anything. I’m grateful to have a job (Nadel is Curator at Large for the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, UC Davis) and my health. We’re inside and trying to stay safe here in Brooklyn. I have friends who are ill but my immediate family is fine, thankfully.