From The Comics Journal #151 (July 1992)

Drew Friedman’s work, much like that of his father, Bruce Jay Friedman (who authored the seminal black humor novels Stern and A Mother’s Kisses in the early ’60s), trades in the comedy of outrage and absurdity. From the start, Friedman’s comics work has been provocative, assaultive and, most importantly, hysterically funny. Beginning as a chronicler of forgotten and fading celebrities (such as Z-movies star Tor Johnson and I Love Lucy’s” “Fred Mertz,” William Frawley), Friedman’s world soon branched out to include contemporary non-entities such as crooner Wayne Newton and the litigious talk show host Joe Franklin. Friedman’s comic sense embraces the pathetic, cast-off world inhabited by these so-called “stars.” His strips question the very existence of celebrities (without, let’s be thankful, doing the slightest bit of soul-searching or philosophizing in the process). Originally consigned to the critically praised but obscure pages of RAW and Weirdo, Friedman’s work soon found its way into such mainstream venues as SPY, Details and the music-biz trade magazine Radio and Records, the latter finding Friedman’s brand of satire a little too corrosive for its clientele. Friedman has also anonymously reached impressionable youth via his projects for Topps Chewing Gum, including the already-infamous Toxic High card series, a revival of the seminal ’70s series, Wacky Packages (created by Art Spiegelman and other underground cartoonists), and gross-out novelties such as The Barfo Family. In this interview, Friedman talks engagingly and intelligently about his influences, obsessions, run-ins with the great and near-great, skirmishes with the unflattered subjects of his cartoon “tributes” and his painstaking cartoon technique, which gives his accounts of has-beens and never-weres a documentary realism that, in Robert Crumb’s words, captures “a certain flavor of sad old America.”

CHILDHOOD ENCOUNTERS AND OBSESSIONS

JOHN KELLY: So, you grew up in New York City…

DREW FRIEDMAN: I grew up on Long Island. I was born in 1958. I lived in Glen Cove first, and then in Great Neck when I was a little older. I have two brothers — one younger, one older. My father [Bruce Jay Friedman] is and was a writer, and my mother [Ginger Friedman] is in the theater, first in St. Louis, and then in New York. But she gave it up pretty quickly to raise children, though she’s a successful acting teacher; and my father was a magazine editor when I was young in New York City. He edited men’s adventure magazines. Sort of like pulps — adventure stories. He was the first editor of Swank magazine. It came out of Magazine Management. And that was the place that also did Marvel Comics. I grew up going to visit him at his office, and right next to his office was Stan Lee’s little office. At that time, Marvel was just like one or two little offices, and Stan Lee seemed to me to be just a likable old phony with a bad toupee.

KELLY: How old were you at that point?

FRIEDMAN: My father worked there till 1966, so I was a little kid: 5 or 6. I don’t have too many distinct memories of it. At that point, my brothers and I assumed that everybody had a father who worked at a comic book company. So, we got all that stuff for free, and we had piles of that stuff brought home to us, piles of Marvel comics. But Stan Lee, at that time, wasn’t a big shot. Marvel at that time was no big thing. In the early ’60s, it was just starting to garner its reputation. I guess it started with the college students. But back then, they were just a couple of small offices: Stan Lee, his secretary, and a couple of artists who would come by. I had no idea who they were. It could have been Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko and Don Heck and those guys. They would drop by the offices and drop off their work. The Marvel office was connected to my father’s office, just partitioned. There was a comic book section and the magazine section. It didn’t seem like anything special to me.

KELLY: So, you were getting all of these free comic books…

FRIEDMAN: It was great to get piles of free comic books but even then I knew that they were real stupid. I wasn’t all that interested in Marvel comics, muscle-bound dopes in tights flying around punching each other… but now they’re sensitive dopes. Even when I was getting piles of them for free, I’d only glance at them and then put them away. They didn’t do much for me.

KELLY: Were you reading Famous Monsters of Filmland at that time? Were you interested in that?

FRIEDMAN: Yeah. MAD magazine, Famous Monsters, Creepy, Eerie… the kind of stuff that you’d buy on the newsstand. It was available to every kid back then. That seemed like the kind of stuff you were supposed to buy. My parents gave us whatever we wanted; they were pretty liberal. In fact, they encouraged us to read comics and monster magazines. It was at school where we got into trouble for reading them. My father, at that time, was writing for Playboy magazine a lot, so Playboy was always laying around the house. It was no big deal. So, we were able to get whatever monster magazine we wanted, our copies of MAD… whatever. It was always given to us. It wasn’t stuff we had to hide.

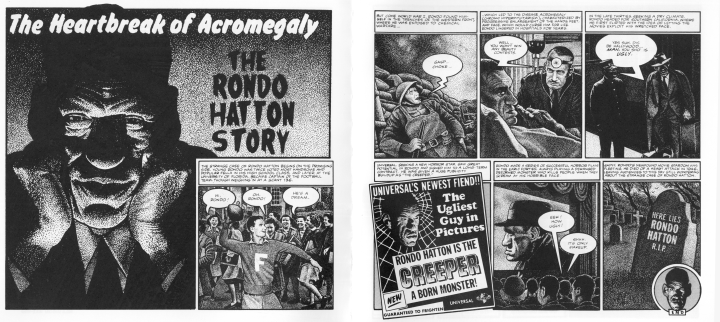

KELLY: Did you develop a fascination with those characters in the monster magazines?

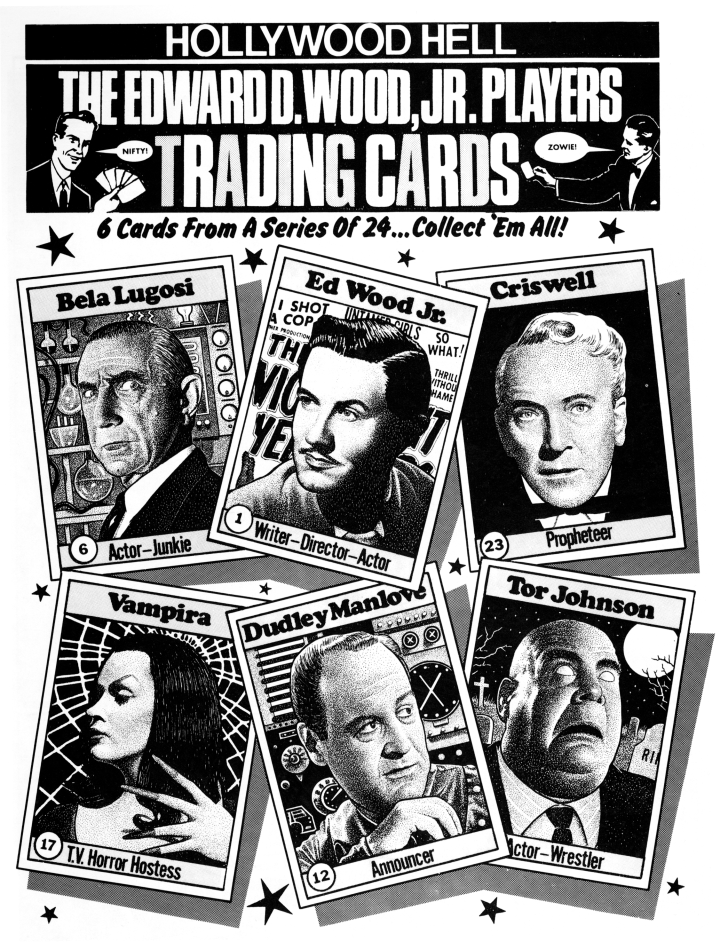

FRIEDMAN: I guess subconsciously they’d stay with me. Famous Monsters of Filmland, especially. Just looking at the photographs in every issue. The writing was pathetic; just a stupid, jokey kind of cornball writing. The main thing was the photographs. The first time I saw Tor Johnson was in the pages of Famous Monsters.

KELLY: What did you think, at that point?

FRIEDMAN: He looked amazing! He was the perfect movie star. It was one image that just stuck there for a while. I guess it had to come out sooner or later in my work, but I saw photographs of him in the movies like Plan 9 from Outer Space. I saw these things years before I saw the actual films. I grew up looking at those photographs and thinking that those films were just going to be amazingly great when I finally saw them. Plan 9 and Bride of the Monster and all those Ed Wood-type films.

KELLY: When did you get around to seeing those?

FRIEDMAN: Not till the video explosion. Although Plan 9 from Outer Space was shown on TV in New York in the early ’60s. I was too young then to have been aware of it. I finally saw it around 1980 on video, or cable TV in Manhattan. I knew then that it was supposed to be a bad film. Those crappy bad movie books by the Medved brothers came out saying that this was supposed to be the worst film of all time. Ed Wood was being saluted as the worst director of all time, and Plan 9 was supposed to be the worst film, but that’s not really true. The worst film of all time, to me, is whatever Meryl Streep’s last film was. [Laughter.] The worst films are usually boring films. And Plan 9 is anything but boring. Actually, the worst film of all time is Last Year at Marienbad. Hands down. I had a VCR pretty early on, in 1978, so I got a copy of that, and had Plan 9 parties. Now, I sort of wince when I think about it, because it’s such a Yuppie thing to do, to have video parties. But I wanted to show that film to as many people as I could.

KELLY: In a way, it seems like you’ve turned the whole country on to some of these guys like Tor Johnson.

FRIEDMAN: Maybe. That’s flattering to think about… but the people I know knew about Tor Johnson long before I ever drew him. I hope I’ve turned people on to that kind of stuff, but that was never my mission. Tor Johnson was just someone I was compelled to draw, mainly because he just fit into the great tradition of comic characters with no eyeballs. His character, Lobo, had no pupils. He just followed in the tradition of Daddy Warbucks, from Little Orphan Annie. Or Dondi. Tor Johnson was just the next in line. I liked the photographs of him. Big, fat bald guy with white eyes in a black suit and a tie, always in a tie. Even though he was a zombie, he’s supposed to be dead, roaming around in graveyards, he always looked spiffy. He was dressed to the nines. And then they paired him up with Vampira…. You see [Plan 9], and it’s just them roaming around the graveyard. There’s no dialogue between them. They were just striking photographs.

KELLY: Is there a Tor Johnson of the future?

FRIEDMAN: If there is, I wouldn’t be aware of him. I see maybe one or two films a year, and I don’t watch any current TV shows. I just don’t have much interest. I guess I like old movies and TV shows; I like things that are black-and-white. I don’t like color TV or movies. If I watch old movies on video, they’re usually black-and-white. I don’t know why; I draw in black-and-white, and I’m just not that interested in exploring color. I don’t know. I don’t think there are any future Tor Johnsons. I don’t think anybody could fill his shoes again. He cast a giant shadow. [Laughter.] That’s what they said about Sinatra, but it applies to Tor as well. Tor had a son, Carl Tor, who looked just like his father, except he had a big black pompadour. He appeared with his father on You Bet Your Life, Groucho’s show. And then Tor has a grandson — I think Tor III — who’s out there. His son, Carl, was a police officer in San Fernando, and loaned Ed Wood all the police uniforms that appear in Plan 9 from Outer Space. He actually appeared in Plan 9 himself. And the grandson was just interviewed for this documentary on Plan 9 that’s about to come out on video. I heard that the grandson looks somewhat like Tor, but there’s no trace of any Swedish accent. You couldn’t really tell Tor was a Swede, either. He sounded all-American to me. He is missed. I’m doing a series of cards for Denis Kitchen called The Ed Wood, Jr. Players Trading Cards.

I did some of them in Heavy Metal originally, and then they were in a Fantagraphics book. Now I’m doing them as cards, only because there’s this big boom in trading cards right now. Also, this book just came out about Wood’s life story [Nightmare of Ecstasy by Rudolph Grey]. It talks about Wood’s fascination with angora, and all that stuff. His life as a transvestite; it also mentions some other famous transvestites that we didn’t know about before, like Danny Kaye and Tony Curtis… I met Tony Curtis when I was a little kid. He was in one of my father’s plays, Turtlenecks. The play was supposed to open on Broadway, but it didn’t. It closed out of town in Philadelphia. Curtis was a nice guy, real sweet. A little too nice… my brothers and I maybe should have suspected something back then. At that time. my father had quit his job at Magazine Management because he was having success as a novelist and as a playwright, and then as a screenwriter. Which is mostly what he does now. He writes for movies and TV. My brothers and I grew up in a house where celebrities would drop by — mainly writers. We got to know Jules Feiffer, Nelson Algren, who wrote The Man with the Golden Arm and A Walk on the Wild Side. He died a few years ago, and his work has started coming back into vogue. It’s all been reprinted lately. My father was part of that group of New York writers. They all used to hang out at Elaine’s Restaurant on East 88th St. which was one of the big literary hangouts in New York City. My brothers and I would get dragged up there. We took it for granted, these people being around — actors, writers, and so on. We just figured that was the way things were. In the mid-'70s, 1975, we were staying with my father at his summer house in Malibu, and all of the sudden we got invited to Groucho Marx’s house. Groucho was living with that woman, Erin Fleming, at that time.

KELLY: Was he in a wheelchair?

FRIEDMAN: No. He was on his feet. It was a year or two before he died. My two brothers and I and my father went to have dinner at his house. It was a memorable experience. Groucho was on top of things. He walked out, as soon as we got in the house, in little shorts, and he had a shirt on with all the Marx Brothers’ heads on it. They were Hirschfeld faces. He came walking out towards us and he said to my father. “It’s great to meet your three lovely daughters.” We all had long hair at the time. The whole night was punctuated with one-liners. A guy came in and said, “My name is Mark,” and Groucho said, “What’s your first name, Trade?” Little Grouchoisms like that, but they seemed funny. We lived in Great Neck, Long Island, at the time, and the Marx Brothers used to play at a theater in Great Neck called “The Playhouse,” which had been a vaudeville theater, and then turned into a movie theater which we used to go to. We knew there was an old organ in the back of the theater, a big old organ that we assumed was part of the vaudeville days. My brother Josh asked Groucho, ”Do you remember the big organ?” And Groucho said, “I used to have a big organ myself.” Josh wrote about the experience in New York magazine. A day after the dinner we had with Groucho, we got another call saying, “Groucho would like to have you back next week. He’s having Mae West as his guest. They haven’t seen each other in 40 years.” We turned him down: we didn’t go. We just took it for granted. I’m kicking myself to this day.

KELLY: Were you and your brothers into the same things?

FRIEDMAN: Yeah. My younger brother’s named Kipp. We all collected comic books and were into monster magazines and MAD and all that stuff. Josh was more into music than we were; he played guitar. That’s what he does, basically, for a living now. He lives in Texas and he plays in blues clubs. He’s a popular blues musician.

DRAWING FROM EXPERIENCE

KELLY: Were you doing comic strips back when you were kids?

FRIEDMAN: I was drawing from an early age… we didn’t start collaborating until the late 1970s. The first strip we did together was the “Andy Griffith” comic. But I was always drawing. I had some artistic ability when I was young. I was always encouraged, especially from my mother. Both my parents encouraged us to do whatever we wanted. Josh was encouraged to be a musician, I was encouraged to be an artist; they were real good about that. I always liked to draw cartoons. At a really early age, I liked to imitate what I was looking at in MAD, and the Topps cards I was buying had a real strong influence, too.

KELLY: What did those drawings look like?

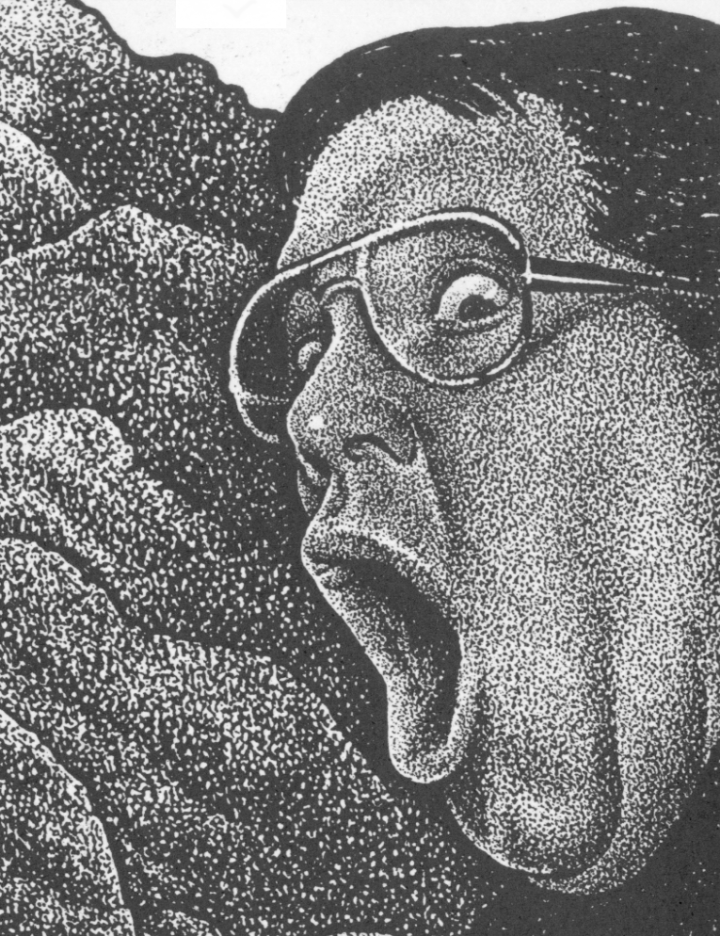

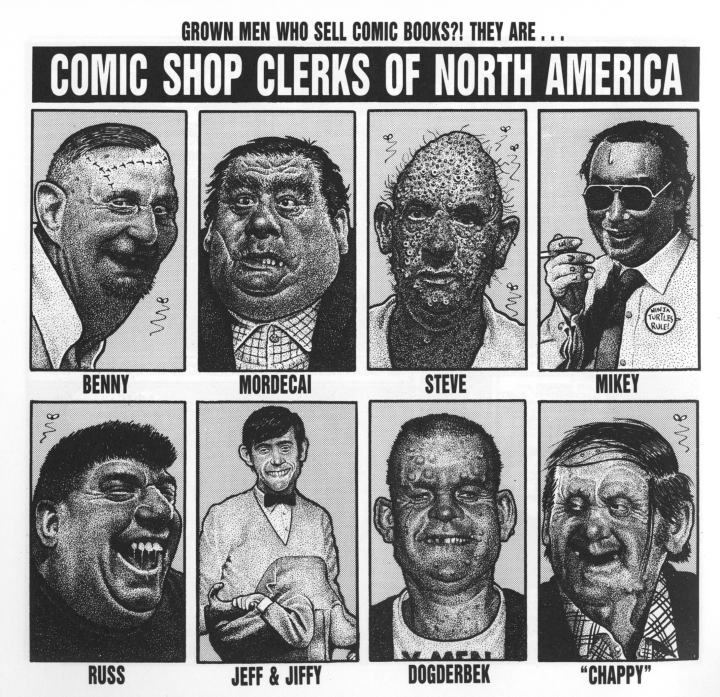

FRIEDMAN: Ugly faces. To this day, I’ve always had a fascination with drawing the ugliest possible face. I really enjoy getting into the detail of drawing a disgusting, horrible ugly wrinkled pock-marked face.

KELLY: Were you fascinated by those types of faces when you were a little kid?

FRIEDMAN: Maybe subconsciously. Maybe that was one of the strongest influences from Famous Monsters; the fact that we were so absorbed…. At that time, in the mid-'60s, there was this big monster fad going on all around us — in the movies, in magazines, in books and TV and toys. It was a good time to be a kid. So, yeah, I guess that was a real big influence for me. But from an early age I was drawing first monsters, and that turned itself into strange-looking people, ugly people. I wasn’t drawing comics when I was a kid. I didn’t really draw comics till I was about 20.

KELLY: Did you have any training before you started drawing?

FRIEDMAN: Not really. I went to the High School of Music and Art, up in Harlem, but I got beaten up on the subway so my parents pulled me out of there and put me in a private school. But I was more interested in drawing on desks than drawing in art classes. I wasn’t interested in doing the kind of art you were supposed to be doing… I wasn’t interested in drawing houses or trees. So, none of my art teachers ever liked me when I was in grade school and high school. They just thought I was some kind of disturbed individual, which I guess I was.

KELLY: I’ve heard about some of Harvey Kurtzman’s classes...

FRIEDMAN: What you’ve heard, I’m sure, has probably been exaggerated. The School of Visual Arts and college in general, to the people I was hanging out with then was sort of an extension of high school, 13th grade. We were taking cartooning classes, and always thought that cartooning should be fun; it’s not a serious occupation. We had maybe more fun than we were supposed to in those classes. Maybe we went a little too far sometimes.

KELLY: Were chairs thrown out windows?

FRIEDMAN: Maybe one time. I think that’s really been exaggerated… people were thrown out windows.

KELLY: Were teachers reduced to tears?

FRIEDMAN: I’m afraid so. [Laughter.] It wasn’t planned that way. It actually did happen where a teacher was reduced to tears. It had to do more with a whole crescendo of incidents building up into what seemed like a nightmarish bizarre surreal situation. All of a sudden, in this class, there was non-stop screaming and throwing things and Three Stooges noises. It built up to such chaos that I felt like crying. [Laughter.] People would say that I was possibly the instigator, the ringleader, but there was nothing the teacher could have done at the time. He left the room, composed himself, came back and said, “Let’s calm down a little bit.” And we did. It was all real innocent fun. It was cartooning class. You were supposed to have fun. Harvey Kurtzman encouraged everybody to have fun in his class. You blew up balloons; you were supposed to have a wacky time. It wasn’t a serious class in sequential art, or comic breakdowns. Harvey wasn’t interested in that. He was more interested in teaching gag cartoons, for some reason. Kurtzman felt that there was nothing more noble in the comics profession than gag cartoons: guys who do single-panel cartoons for the New Yorker. To Harvey, that’s what every cartoonist should aspire to — to be the next Peter Arno or Charles Saxon.

KELLY: Did he ever do any of that himself?

FRIEDMAN: No. You think of Harvey Kurtzman as the brilliant mind who created MAD magazine, and all of the other magazines he did, and Little Annie Fanny. He was never a guy who did single-panel cartoons, although he was cartoon editor in Esquire for a year or two. He bought stuff like that. Most of the guests he had come into the class were New Yorker cartoonists. Jack Ziegler or Bill Woodman. Someone like that. Occasionally, he’d get someone like Neal Adams or Joe Orlando, some comics guy came in. Crumb would come in occasionally, too. For the most part, Harvey was most interested in teaching single-panel gag cartoons. That was what the class was about. I don’t understand why…

KELLY: Besides Kurtzman, you had Art Spiegelman, and Will Eisner…

FRIEDMAN: It was a real interesting time to be at that school, I think. And, once again, I think I took it for granted. I was just a kid back then, 18 or whatever. These guys were your teachers. It wasn’t like, “Now you’re going to have the legendary Will Eisner, and at 3:00 you’re going to have the legendary Harvey Kurtzman, and at 6:00 the soon-to-be-legendary Art Spiegelman…” I didn’t treat them like they were anything special. Not too many people did. There was a time when I took Eisner’s class, and I think there were two other students in it. Nobody really cared that much. It was nothing special. But that was the environment in the School of Visual Arts. Some of the other students in my classes at the time were Mark Newgarden — that’s where I first met him — and Kaz, Peter Bagge was there for a while, Keith Haring was going there at the time. Dan Clowes was at Pratt. I didn’t know him back then, but his friend Mort Todd went there. He was part of that clique. Guys who were up-and-coming cartoonists were students and the teachers were these legendary cartooning figures. It was a real interesting time. Similar, in a way, to what was happening in Seattle maybe couple of years earlier with Matt Groening and Lynda Barry and Charles Burns. They all seemed to be in the same school, in the same town. It was like an East Coast version of that, maybe…

AIMING TO DISPLEASE: EARLY RAW STRIPS

KELLY: Did you get a lot out of Kurtzman, Eisner and Spiegelman as teachers?

FRIEDMAN: Not especially. The best thing I got out of it was connections, and friends. Art Spiegelman and I did not really hit it off at first when he was my teacher. For whatever reason, we didn’t see eye to eye on a lot of things; he didn’t give me good grades. I didn’t deserve good grades cause I wasn’t real interested in paying attention to his slide lectures on the history of comics. At that point, in 1980, he was starting RAW magazine, so I was in the right place at the right time. He was trying to put stuff together, so he picked Mark Newgarden, Kaz and myself out and ran our stuff in the first issue. They were looking for new people and new, interesting stuff, and they had a lot of European stuff they were going to run, and they wanted to run some new American people…. The strip of mine that appeared in the first issue was the “Andy Griffith” strip, which had run in Harvey Kurtzman’s magazine, Kar-tunz, the year before. It was this real stupid magazine filled with bad cartoons that were drawn all year by his students — real embarrassing stuff, for the most part. Spiegelman saw it there, liked it, and ran it in the first RAW. The second RAW ran the thing about the guy stealing my coat, which I didn’t really want to do at first. Art called me and said, “You gotta do this.”

KELLY: Did he come up with the topic?

FRIEDMAN: No. It was something that actually happened. We were critiquing some of my artwork after hours at the school. And it was in the middle of winter, during a snowstorm, and my coat was hanging by the door. There was a guy, a Black guy, lingering around the door for a while. We didn’t think anything of it, and then all of the sudden my coat was gone. The big ironic thing was that we were talking about making fun of races, making fun of Black people. That’s why François Mouly, Art and myself were there — we were going over this strip where I had snuck this gratuitous racist image in, for no particular reason. Art was having a problem with that. And ironically, a Black guy stole my coat. Later that night, Art called and said, “You’ve got to do that as a strip.” I wasn’t really into doing it, but I did it. He said, “If you want to be in RAW, you’ve gotta do it.”

KELLY: Didn’t Spiegelman get questioned on whether it was in good taste to run that strip? Because that strip, in itself, was maybe racist.

FRIEDMAN: I don’t know about that... there was this thing called the Radical Humor Festival where this knucklehead was angry at Spiegelman because he wasn’t running enough political stuff in RAW. And then this knucklehead said: What about this thing you ran by Drew Friedman about this Black guy stealing the coat?” It became this big to-do. Everybody was pointing a finger at each other, saying it was and wasn’t a racist comic strip, and it should or shouldn’t have been printed…. It got sort of complicated. I don’t think the strip was racist. It was sort of a commentary on racism — that was Crumb’s feeling, too — on the fact that I was young then and I was into offending everybody, I wasn’t singling out any group. If you look at my work, I draw Black people ugly, I draw white people ugly… Josh and I were into that mind frame where we wanted to really shake things up and offend and horrify people. We didn’t care. We were just a couple of punks at the time. So, I gratuitously stuck this Black face in there with giant lips and said, “Give to the United Negro College Fund.” It made no sense; it was part of a strip that was just a bunch of images stuck together. That was one of the images. And then I did the second half, with the Black guy stealing my coat. A lot of people didn’t look at that as a commentary on racism. Those things happen. You can’t please everybody. Trying to offend any particular race was something I was playing around with in my late teens and early 20s, but I slowly got that out of my system. You look at early work by a lot of people, and they’re working that stuff out, too. You look at some early Art Spiegelman panels and there’s some images that some people might think are racist — rubbery Black people with giant lips. You get into hot water when you’re starting out and taking chances. If you want to do interesting work, you don’t want to do the boring kind or shit that so many other people are just happy to do. You’re going to get in trouble. A lot of people think Robert Crumb’s a real racist, but I think that’s an insane thought. The only music Crumb listens to is music by Black people. He’s got a lot of love for Black culture. A lot of people just really miss the point. They only see things at face value. You can get in trouble when you don’t play along by any particular rules. I try not to: to this day, I try to do what I want to, for the most part. Although I’ve gotta make money, and so I take jobs that, maybe a few years ago I wouldn’t have.

KELLY At this time, in the early ’80s, was Josh writing a lot of your strips?

FRIEDMAN: At the beginning, Josh was the writer and I was the artist. On all the early strips we did…

KELLY: Who would come up with the idea for the strips?

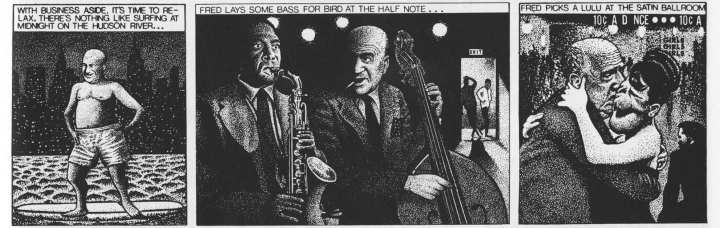

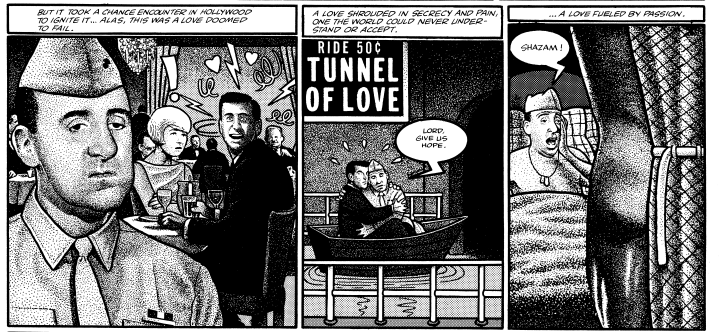

FRIEDMAN We’d kick it around together. The first strip we ever did was the “Andy Griffith” comic, about the Black guy coming to Mayberry and getting lynched. And it was 1978 when we came up with that idea. We came up with it because Josh had been an editor at Screw at the time, and he had been making connections in the magazine world and was starting to be published elsewhere. He was published in New York magazine and Penthouse ran a short story by him. I was starting to go to SVA. I started getting printed in Screw, doing goofy cartoons in there. And then we started kicking around some comic strip ideas, just on a whim, and only for ourselves, and to show to our friends. We honestly weren’t thinking about actually publishing stuff or making money by doing comics. We just did it to amuse ourselves, mainly. I don’t know who had the idea to have a Black guy go to Mayberry, but that was the first one. We wanted to do parodies of old TV shows. That seemed to make sense at the time. We were both into that stuff, so we both thought that was a natural idea — a Black guy going to Mayberry. He scripted it, and I drew it, and it got printed in the Kurtzman’s school magazine, and then it wound up in RAW. It got some good reaction from people we showed it to. And the next strip we did was about Fred Mertz’s life after the cameras shut down. That sort of became the theme — to show what happens when the cameras go off, what happens late at night. Once again, we didn’t sit down and say “OK, this is the kind of strip we’re going to do. We’re going to do comic strips about the private lives of celebrities.” It just felt comfortable, and we just went along from one strip to another. That’s when we were starting to get printed in High Times magazine, and RAW. We were starting to get some good response. People were starting to notice that this stuff was kind of funky and weird. I was comfortable with Josh as a writer, and we were thinking along the same lines back then. We had a lot in common, I guess. We had the same kind of nasty sense of humor. That was a good working relationship at the beginning. Josh was very encouraging as far as getting me to draw different types of strips.

KELLY: Would he suggest changes in the drawing?

FRIEDMAN: Not really. As far as artwork, I was all on my own. He would give me reference if I needed photo reference. There were times when I wanted things changed in the writing; he was pretty set in his ways, as far as the script. He considered himself the writer. And usually he was right: the script was fine. Occasionally, I would have a problem with something, and we’d talk it out or we’d change it or make additions to it, but I was content in letting him write his own scripts, and I was happy with the results, usually. I really thought a lot of his scripts were screamingly funny. I would crack up into hysterics before I would actually draw them, and it would be a pleasure to actually draw them and bring them to life. I was really getting into that kind of nasty humor. At first, the humor was the most important aspect. A dark humor. Then we started getting into more biography kind of strips. We started doing longer strips; the first one we did was “The Joe Franklin Story.” It was the story of his life, basically — fact and fantasy together. It started with his mother giving birth to him, and it just went on from there. We both grew up watching Joe Franklin on TV. We were both always amazed by this strange-looking little person who had his own talk show since the early ’50s and just wouldn’t go away. We had to do something with the guy. We decided that the comic strip was right.

KELLY: How did you research it?

FRIEDMAN: That was Josh’s script, with some changes by me. He went to the Library at Lincoln Center, where they have a huge section on just about everybody who’s ever been in show-business huge clipping files on celebrities and writers. He worked from that, and from articles about Joe Franklin that he had clipped out over the years, and he turned it all into this weird strip chronicling the guy’s life. That was 12 years ago, and he’s still going strong, for whatever reason… I haven’t watched to show in a couple of years, for my own reasons. I guess he must have some kind of following. I can’t say that much about Joe Franklin because he sued me once… it’s touchy.

KELLY: That was after the second strip...

FRIEDMAN: Yeah, the later strip that I did myself. Probably, there’s nothing wrong with talking about Joe Franklin, but you never know…. He might subscribe to The Comics Journal and he could sue. So, if I say anything derogatory about him right now, I could see him suing.

KELLY: Can you talk about the lawsuit?

FRIEDMAN: Oh, the lawsuit I can talk about. He sued over a strip that I did called “The Incredible Shrinking Joe Franklin” that was collected in Persons Living or Dead. But it first appeared in Heavy Metal. He sued Heavy Metal, National Lampoon, the owner of Heavy Metal, the publishers of National Lampoon, the editors of Heavy Metal and me.

KELLY: What was the total figure of the suits?

FRIEDMAN: The total amount he was asking for was $40,000,000. And it basically came down to the fact that he’s very touchy about his height. So, the fact that I was showing him shrinking away getting smaller and smaller, disappearing, was too much for him. He didn’t sue over the strip where we showed him being born, and we showed him going through all these horrible things — the strip that Josh wrote, “The Joe Franklin Story.” But he did sue over the more light-hearted strip. Also, the fact that the strip said he was going to lose his job at WOR, and also the fact that the strip said “To Be Continued” at the end. That was too much for him. The suit was dismissed; it never got to court, fortunately or unfortunately. It coulda been fun…

KELLY: What did you feel when this happened?

FRIEDMAN: I was amused by it. I was going along with it. At the time, in 1983, when he sued, maybe I had $100 in the bank. He was looking for $40,000,000.00... I suppose he could have put a lien on whatever money I might have made. I think he wanted to sue the first time around, over the first strip, but he didn’t see any money. But when the second strip ran in Heavy Metal, he thought that he could make some money out of that. So that’s when he came up with that figure of $40,000,000 which is, of course, a reasonable sum, and he was totally entitled to it if he had won. Water under the bridge…. I guess I learned a couple of valuable lessons from this. I don’t know what they are. I just continued doing what I was doing, even after he sued. I don’t think I toned down my work.

KELLY: Do you ever shy away from doing somebody who you thought might do something similar?

FRIEDMAN: No:, I don’t think Josh or I ever shied away from doing anybody. Public figures are fair game. I think that’s what that phrase means. The public sort of owns them. You can get away with poking fun at whoever you want. One person we did — we didn’t have a problem with him, but a lot of people seemed to think we were stepping over the boundaries to do a parody — was Jules Feiffer. There were some problems with the fact that he seemed like the wrong person to go after, which is why we went after him. We sort of dragged him through the mud. Why should we only go after people… the phrase, “going after,” is not really appropriate, anyway. We knew Jules Feiffer from when we were growing up. When we were little kids, he was in our house. He would come over and eat our egg salad, potato salad, coleslaw and stuff. Also, we found him to be slightly pompous when discussing his works. We had transcripts of some of his interviews. We always found him amusingly interesting because he pontificates on his own work endlessly. Whatever play he’s writing. So, we did this one comic, just to show his bad habits — pulling lint out of his belly button and examining it . Little quirks of his life. Sneaking potato salad from our refrigerator. Getting Reagan. It was kind of silly; not the best thing we ever did. But we caught a lot of flak. A lot of people took it wrong.

KELLY: People in the comics industry?

FRIEDMAN: I think Gary Groth was pissed off about it mainly because he was about to go into printing a whole line of Feiffer books. The one strip Spiegelman wanted to keep out of Warts and All was the Jules Feiffer strip. We argued about it back and forth, about how it was. He felt that since Feiffer was a friend of his, there would have been a problem to run it in Warts and All. So, we had to grit our teeth and pull it out. But that’s OK.

KELLY: I guess it was unexpected that you would do a parody of Jules Feiffer, instead of going after somebody more obvious…

FRIEDMAN: That’s why we did it — to mix things up a little bit. And, I guess, to piss people off. Bob Hope is obvious. Feiffer wasn’t.

KELLY: Have you run into Feiffer since then?

FRIEDMAN: Yeah, I have. I don’t think he ever saw the comic. Or if he did, it didn’t register. It meant nothing to him.

KELLY: I see that you have a bunch of Jules Feiffer’s books. Do you enjoy his work?

FRIEDMAN: I used to think his stuff was great — really important and valid. I’ve never had a problem with his work. Maybe lately, but I don’t pay much attention to that. The early stuff is great. As a kid I loved it. The fact that we did a comic strip about him wasn’t because we don’t like his work. That’s a good example of what I was talking about before: I’ve always admired Jules Feiffer. The origins of the comic were based on reading interviews with him where he comes off slightly pompous. Josh wrote the comic strip. I basically received the script from him and drew it. I was behind doing it. We talked about it before he wrote it — “Let’s do a parody of Jules Feiffer.” But it was mainly to hopefully piss people off, and it did. That also applies to a lot of the other strips. They were really written by Josh. His perspective is probably different from mine on a lot of this stuff, too.

KELLY: Is Josh still writing?

FRIEDMAN: Yeah, but he and I aren’t really working together anymore. We haven’t worked together in about two years. We got to a certain point where we had less and less in common, I think. Also, I was more interested in pursuing my own writing. It wasn’t really a decision we made; we just stopped collaborating on comics. I t was probably more my doing than his. Josh moved to Texas a few years ago, and started pursuing his music career more earnestly, although he still writes articles and stories for different magazines.

KELLY: Have you ever run into anyone else that you’ve parodied? Frank Sinatra, Jr., or somebody?

FRIEDMAN: No, I haven’t run into Frank Sinatra, Jr. I don’t know if he ever saw the comic we did about his life story. But I have an autographed picture of him that somebody got for me after the strip appeared. It hangs over my drawing table to inspire me. There was talk about Jim Nabors suing Fantagraphics when Persons Living or Dead came out — the Rock Hudson/Jim Nabors love affair strip [“Strange Bedfellows”].

KELLY: They weren’t ever mentioned by name in that strip, were they?

FRIEDMAN: No, but it’s obviously them. But he didn’t sue. Because Nabor’s lawyer called and talked to Gary Groth about that, and I think Groth said that it might be a smarter idea not to sue, because if you do sue, this case might hit the press, and then the Jim Nabors/Rock Hudson connection would be in the newspapers, and did Jim Nabors really want that? If you don’t sue, if you let it go, it’ll go away. And they didn’t sue, but there was talk about it. And that could have been an interesting lawsuit. That was the only other talk about lawsuits. Otherwise, I haven’t had any problems. Joe Franklin was a special case because he’s litigious. He’s an avid suer. He’s threatened to sue other people as well, including Uncle Floyd [a legendary New York/ New Jersey TV personality] and Billy Crystal, who’ve imitated him. And others, as far as I know. You sort of expect it. The Joe Franklin thing is behind me. I have no interest in him anymore. I haven’t watched his show in years. He dissed me.

KELLY: You’re not ever going to appear on the show, or…

FRIEDMAN: No, I don’t think I ever will. I don’t think I’ll be invited; I don’t think I’ll ever get on. My mother’s been on the show. She was on it just a couple of years ago. She’s an acting teacher now. She was talking about her acting classes. She was on for about half an hour. At the time, I don’t think Joe knew the connection.

KELLY: Who else was she on with?

FRIEDMAN: Poetess, a sculptor and some other guy who I think was an acting teacher — it was the typical Joe Franklin panel, except for my mom. Also, by the mid-’80s, everybody was making fun of Joe Franklin. When Saturday Night Live picked up on the whole Joe Franklin thing, I lost interest in it almost totally. It became mainstream, making fun of him. And he also appeared in Ghostbusters…. He sort of became, like SPY magazine pointed out, one of these celebrities that we used to laugh at who are now laughing at themselves. Joe Franklin knows that he’s a goof, but he knows that it’s enhanced his career.

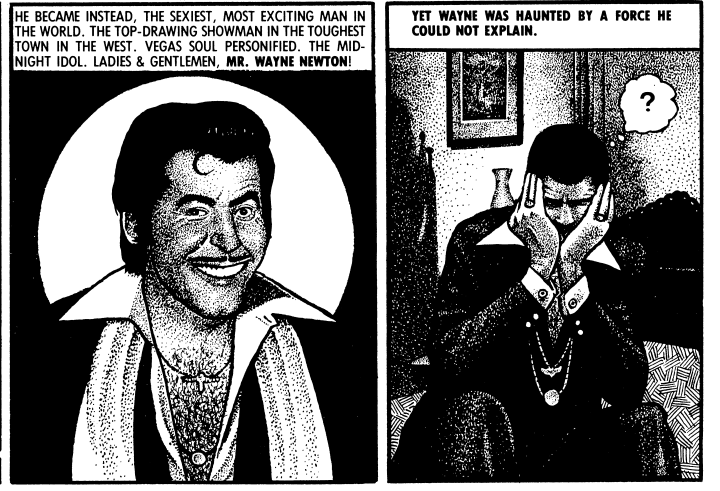

KELLY: Like Wayne Newton.

FRIEDMAN: Same thing with him. I wouldn’t do a Wayne Newton parody now. He knows he’s a parody. Maybe somebody had a heart-to-heart talk with him: “Wayne, you’re getting old now, you’re gonna be 50. Why don’t you pose with those two guys from Wayne’s World on the cover of SPY? It might help your career out a little bit.” That’s what seems to happen a lot.

KELLY: Back when you did that biography strip on Wayne Newton, did you ever hear anything back from him?

FRIEDMAN: No, not at all. It appeared in High Times; I have no idea if he ever saw it or not. There was no reaction when it appeared in the Fantagraphics book. Which is the way it should be. We weren’t looking for any reaction from Wayne. We never sent him copies. If he saw it, I couldn’t care less about what his reaction would be. Wayne wasn’t the target audience. [Laughter.]

KELLY: His audience wasn’t the target audience.

FRIEDMAN: Josh and I were his audience. We attended a Wayne Newton concert shortly after we did the comic. We were so curious, after being so absorbed in the world of Wayne Newton, that we actually had to go and see one of his concerts. And he came to New York and played down at the World Trade Center.

KELLY: How was that?

FRIEDMAN: It was horrible. [Laughter.] First of all, it was put on by something called “Integrity Productions.’’ They oversold it — it was a 3,000 seat thing and they oversold by about 2,000 seats. So, there were people fighting to get seats. The whole thing was a sleazy, horrible nightmare. We walked out after about half an hour, after half of it. He’s the king of entertainment, but we could only take so much. We fled. But you sort of have to do that one time. The best thing about it was seeing Wayne Newton wannabes in attendance. Guys walking around dressed like Wayne, with his moustache… sort of like Elvis impersonators.

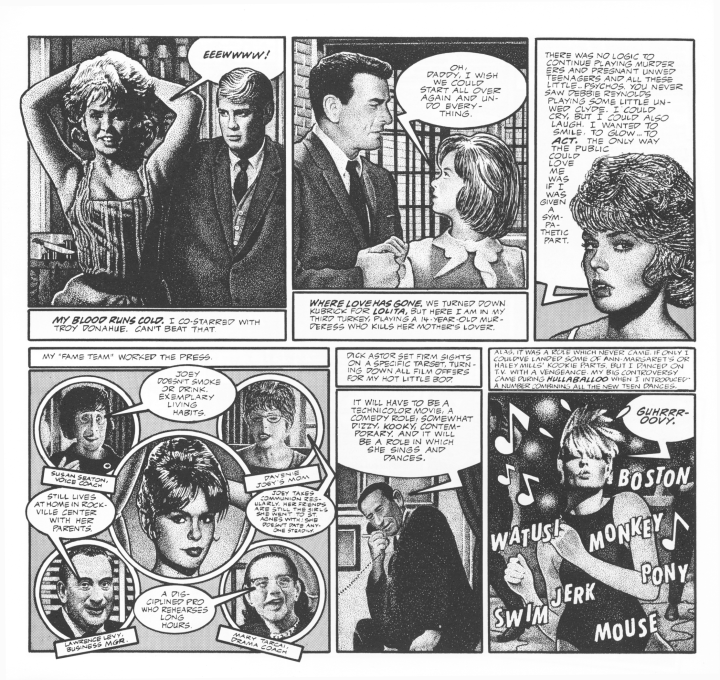

KELLY: In researching that strip, was it the same thing? Josh going to the library?

FRIEDMAN: That was basically Josh’s script. He got a lot of old photographs and articles out of Lincoln Center Public Library. And there were clippings he had saved from the New York Post. At that time, Wayne Newton was having a feud with Johnny Carson that was making the cover of the Post. I think four times we did big show-business biographies — Joe Franklin, Frank Sinatra Jr., Wayne Newton, and the last one we did was “The Joey Heatherton Story.” You can’t go off with that kind of genre of comic strip. We did the Heatherton strip about three years ago. We did that one over a process of a year. Originally, it was supposed to appear in National Lampoon, and then they lost interest in running it. But then new people came into Lampoon who did want to run it, so they finally ran it in there. I was working on it, and then I put [it] aside for a year or so, and then I got back and finished it up. It was going to appear in Warts and All, and so I wanted to finish it for that. Once again, it’s the same process of Josh saving clips on Joey Heatherton over the years and finally compiling it into an epic biography mixing fantasy and reality.

KELLY: Do you think Josh had more interest in these personalities than you did?

FRIEDMAN: I think we might have had the same amount of interest. But he was more interested in writing that particular kind of strip. Whereas with my writing, I think I was going into a stranger direction. In the strips I did for Heavy Metal early on, when I got in there as a regular, I wanted to explore a more surreal kind of theme. I didn’t want to stick to any kind of rigid format. The strips I did for Heavy Metal were dealing with real people, or kind of sub-celebrities, I wanted to play around with things a little bit...

KELLY: “Joe DeRita of the Apes?”

FRIEDMAN: Yeah, things like that. A world populated by Ernest Borgnines and Arthur Godfrey, or William Bendix sightings. It was more interesting picking sub-celebrities or mainstream celebrities and playing around with them in a more surreal kind of way than Josh and I had been doing. We had been doing more of a standard biography kind of strip.

BIGGER MARKETS, BIGGER HEADACHES

KELLY: At the time you guys were bringing these strips around to all the alternative magazines in New York… was this right after SVA?

FRIEDMAN: Yeah. I was mainly doing comics with Josh. They weren’t paying a lot of money at all. I was doing some illustration work, but I was mainly working on building up the comics. I was working constantly on comics at that point. And they were appearing in things like High Times and Weirdo, Crumb’s magazine, and RAW. A few other places. And then, little by little, I’d go out on my own and start dropping off work at places like Heavy Metal. And that led to Lampoon. At one point, we were submitting strips to Playboy. And they actually bought one strip, but they never ran it. Who knows what they were thinking.

KELLY: What kind of things were they wanting you to draw?

FRIEDMAN: Back then, they were running this dopey comic section, which was really embarrassing, sort of like a watered-down underground comic section. I had one meeting with the cartoon editor up there, Michelle Urry, who I didn’t get along with at all. She thought my work was dark and depressing. I told her Playboy was dark and depressing. It was the one time my father arranged an interview for me. Through his connections with Playboy, he set it up. So, I think Michelle Urry resented the fact that the interview had been set up that way. And she also wasn’t receptive to my work; she just didn’t see it as the kind of stuff her boy Hef would dig. We didn’t get along. A couple of years later, after our first book came out, we were commissioned to do a strip, which we did, and we got paid for it. But they never ran it. It wasn’t a Playboy-style strip. They called because they had reviewed our book; they wanted to see if we were Playboy material. I don’t think we were. The only nice thing about appearing in Playboy was the money — in the mid-’80s they paid a thousand dollars a page, which was nice. I have no regrets about never appearing in Playboy.

KELLY: In the mid-’80s, were you able to live off your cartooning? Were you doing other jobs?

FRIEDMAN:I was living off my cartooning — barely. I was living in Manhattan by myself, eating Kraft macaroni & cheese, and I was able to make a living. I was getting some financial support from my father, just to help out with the rent occasionally but I wasn’t ever worried about not making a lot of money. I just thought things would fall into place, which I think they have. I never did anything but draw. I never had to take any other jobs. I spent most of my time drawing. People thought I was a little strange, working so hard — a man with a mission. But it enabled me to compile an anthology by the time I was 25. I was obsessed with turning out comics. I can’t say why.

KELLY: Do you use a sketchbook much?

FRIEDMAN: Not at all, anymore. I used to draw a lot on the side, when I was younger, but now it’s work for me. My process now is that I work all day, and I don’t want to draw… I’m not like Robert Crumb; I’m not that compelled to draw. I’d rather just draw when I’m sitting at my desk and actually doing work. Otherwise, I don’t want to think about it. I’ll still doodle and stuff, when I’m not at home — if I’m on the subway, or driving on the freeway, or whatever — but I don’t go out of my way to keep a sketchbook.

KELLY: So where do you come up with these faces?

FRIEDMAN:I have a rich imagination, and I also have a photo file. I like to take normal-looking people and distort them, which is always fun. If you look at the cover of Warts and All, those faces came from photographs, but if I showed you the photos, they wouldn’t look anything like what appears on the cover. I like to take a pleasant face and really drag it through the mud. So, I have a fairly big photo file, with all kinds of faces, and that comes in handy. But I can draw without photo reference and make it look like a photograph, with that process of drawing with the dots and filling it out. When I’m working on a comic that I want to finish within a week, or for a deadline, or whatever and I have the photo reference that will help me along, I’ll just use it. Whatever justifies the means to the end is fine.

KELLY: Do the strips you’re doing for SPY require you to read the paper a lot more than you usually would?

FRIEDMAN: No. They come up with the ideas, for the most part, for the drawings I do for them. You have to realize that when you work for SPY, everything comes out of the SPY committee, this cabal of a couple of editors who come up with everything, or at least have to approve everything. One of the criticisms I’ve heard about SPY is that everything reads like it’s written by the same person. It all has that SPY style. So that applies to the drawings I do. A lot of the drawings I’ve done I haven’t cared for, but it has to fit into SPY magazine’s opinion of the world. A lot of people only know my work from my SPY drawings. People don’t even know I do comics. But all in all, I’m very happy with them; I think some of them are funny. Also, I enjoy SPY overall. There’s always some funny pieces in every issue.

KELLY: Which of your SPY drawings do you like the most?

FRIEDMAN: All the ones that ran in Warts and All; I think they’re a real strong crowd. I’ve got about 60 of them now, and I’m going to be compiling them in a book soon. Some of them I’ve been embarrassed by, but I just shrug my shoulders and go along to the next one.

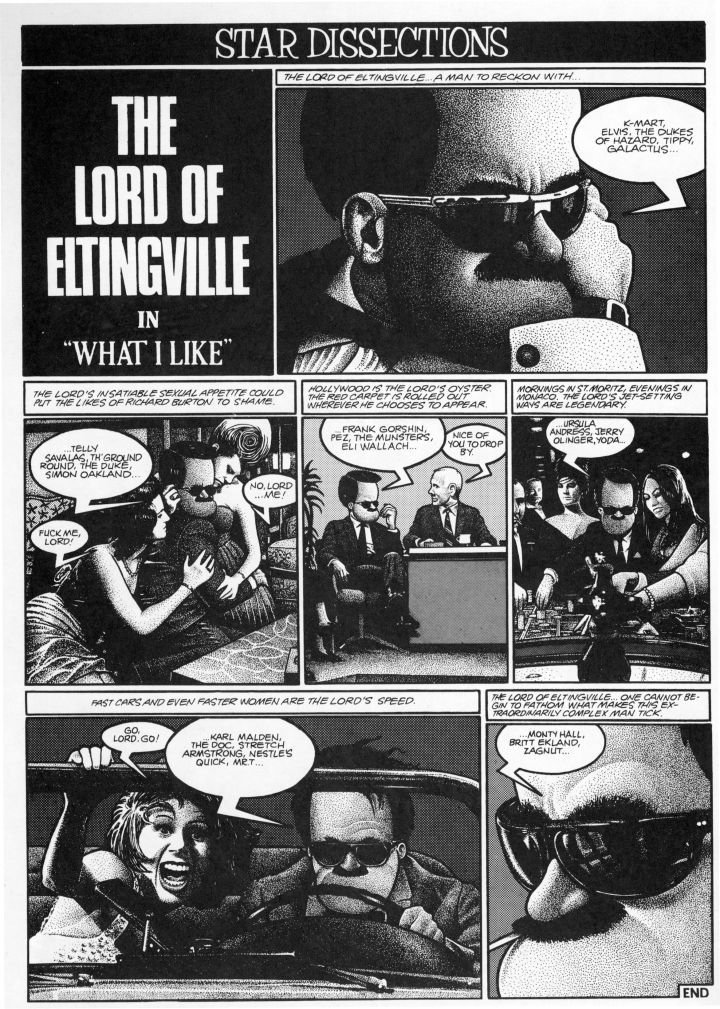

KELLY: You had also done some stuff for Details?

FRIEDMAN: I was commissioned to do strips for them a year or so ago. Details was bought out by Condé Nast two years ago, and they fired the original staff and brought in all new people, and one of the things the new people — British editors — wanted to do was to start a comics section. And they had this script by this screenwriter named Bruce Wagner. He was married to Rebecca De Mornay. Anyway, he was writing this comic strip, like a soap opera along the lines of Twin Peaks, and Details contacted me and told me I was perfect to draw this. And they sent it over to me, and I really didn’t connect with it. I didn’t hate it, but it was not right for me at all: a Beverly Hills soap opera, with characters I couldn’t have cared less about. I didn’t know what direction it was going to go in, and I didn’t want to take a chance. So, they started offering me this huge amount of money, and I continued to say no, and they kept upping the ante, and finally I said, “I’d like to do work for you guys,” because they were offering me so much money that I didn’t want to just turn my back on them altogether. That would have been foolish. I said, “Let me come up with my own thing.” I wrote them a proposal for the Lord of Eltingville, which was a character I had done before in Heavy Metal and National Lampoon.

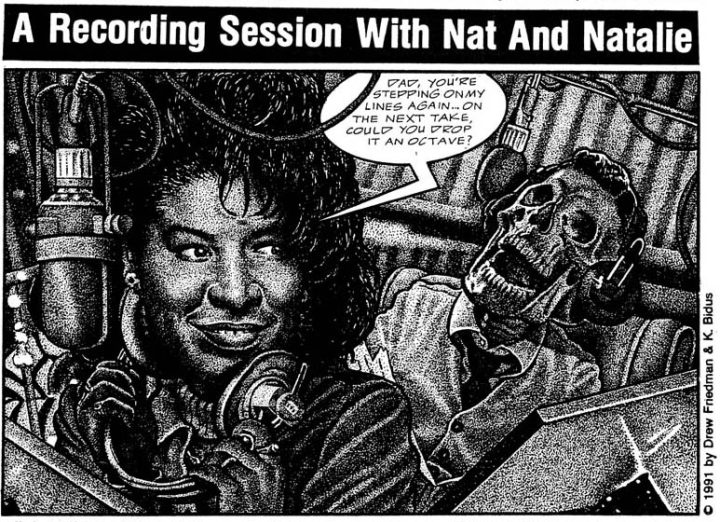

And they accepted that, but they wanted the name changed. I said, “I don’t want to change the name, but what if I elevated him to dukedom?” And they accepted that, so the lord became a duke. I did strips for them for nine issues, I think, before I started to go in different wacky directions that they didn’t quite comprehend. So, the editor and myself decided to finally terminate it. To make a short story long, I also did work recently for a magazine called Radio and Records. Once again, they were contacting me about doing a regular cartoon for them. Radio and Records is a music publication much like Billboard — a trade publication for the music business, but mainly for the radio business. The publisher saw my work in Details and said, “This is the guy we want to do cartoons about the radio and music business.” The weekly publication was completely subsidized by the music business and the radio business; all the advertising came from them. So why on Earth they would want to hire me to come in there and do cartoons that poke fun at the radio and music business was beyond me. But they were offering a good amount of money, so I said, “Yeah, sure. But please realize that you’re going to be hiring me. I’m not going to be doing little cutesy cartoons poking fun at the music and radio business.” I assumed they knew what was coming. But I don’t think that they were prepared for what actually came. I wound up doing 11 drawings for them. But they only printed 8. The third one that they ran was a parody of Natalie Cole singing with her father, Nat, in the studio. It was a drawing of her, with earphones on, and his skeleton propped up near a mic; and she’s telling him to quiet down a little bit; he’s speaking over her lines. And when that ran, the shit hit the fan. Elektra Records called and pulled out all their millions of dollars’ worth of advertising for one year; Natalie Cole’s representative called and said that she would never advertise in there again; they were barraged by letters and phone calls. People were horribly, horribly outraged by that cartoon; obviously, to me anyway, everybody was totally missing the point.

KELLY: Yeah, it perfectly summed up everything that she was doing.

FRIEDMAN: Well, that’s what I and my wife Kathy, who wrote it with me, thought. Obviously that was the statement that we were trying to make; that Natalie Cole, in order to revive her career, took her father’s old songs and sung over them. It’s sort of the equivalent of Paloma Picasso painting over her father’s paintings. How would people feel if Julian Lennon sang over his father’s Beatles recordings? People would be a little outraged. I don’t know why it’s okay for Natalie Cole to do it, but I guess it is, ’cause everybody seems to love what she did. She got 40 Grammys. I don’t know if she got permission from her father; he’s been dead for 25 years. I don’t know if he’d be too thrilled about it. So, it was just a cartoon poking fun at that, or at least pointing out what was happening. Got in a lot of trouble for it, and soon after, Radio and Records terminated the contract. [Laughter.] But they had signed me for a year. So, I squeezed them. I didn’t let them out of the deal too easily, let’s put it that way.

KELLY: You got your money.

FRIEDMAN: I got my money plus. So, it worked out for everybody. Even Natalie. She got the sympathy vote at the Grammys. [Laughter.]

NATIONAL LAMPOON AND FUN AT TOPPS

KELLY: Up until recently you were editing the comic section at National Lampoon, which you started on about a year ago. And it seemed really exciting, for a while.

FRIEDMAN: At first it was exciting for me to come in there. I was hired by a friend of mine, George Barkin, to edit the comics section. They had a few cartoons that were left, but the main job was to edit the comics section. Originally, the whole thing was exciting to me — bringing in a lot of new, talented people, people whose work I had liked, and hopefully giving them a wider audience. Lampoon, at that time, had a new owner, and there’s a lot of talk about reviving it to its former status. It had been awful for close to 10 years. But then all these new people were hired, and it really looked like something special was going to happen. It was going to come back; compete with SPY, I guess. At first, everything was cool, except that all the old contributors — people like Shary Flenniken, [Charles] Rodrigues, Bobby London — were unceremoniously dropped, which might have been a mistake. In retrospect. It happened too quickly. The new editor came in and completely wiped out these legendary Lampoon people. They were told that their work was no longer wanted. Then they brought me in. I had nothing to do with the dismissals. Some people might have perceived that I was the one, but I had nothing to do with that. I was brought in knowing that I was supposed to bring in all new people, but not knowing that all the old people were going to be scrapped. My feelings were, “OK, all right. I’ll contact Dan Clowes and Kaz and Doug Allen and Robert Crumb and Kim Deitch and Art Spiegelman and Charles Burns and Justin Green and Mark Newgarden…” Which I think is what happened at the beginning. My pitch was: “We pay $600 a page, and you can do whatever you want, as long as somebody might perceive it as funny, since it’s a humor magazine. You have total freedom. I trust you.” For the first few months it worked out real well. Most of the people I asked to come in came in, plus some new people, like Chris Ware. It was fun to make these people some good money doing single page comic strips and get them some national exposure — more than some of them might have been used to. But George Barkin was fired pretty quickly, and the new editors started hassling me about some of my choices: “Dan Clowes is not so funny,” and — why are you running Mark Newgarden’s strip this month? It’s all about shit. And Kaz’s strip is all about shit, and Gary Panter’s strip is about shit — what is it? Your friends have a shit fixation?” [Laughter.] Ironically, one month, three strips had the subject of bowel movement. The younger editors were giving me a hard time. One editor in particular thought he knew all about comics because he came from another comic book company. He wanted me to run strips like “Fish Police” and “Hamster Vice.” He kept showing me issues of that kind of crap, and saying “Why don’t you run stuff like this?” So, the odds were against me. Little by little, I lost interest in the thing anyway. I stayed on working at home, answering the mail and so on. But finally, it turned out to be an ugly situation. Lampoon’s new publisher was not paying people. I’m no longer working with them. I think Lampoon is in a lot of trouble right now. It hasn’t quite folded yet but it looks like it might very soon. They shut down their New York office. I think the Lampoon exists now in name only. There really is no longer a magazine. A new issue might come out… but it should really be put to rest.

KELLY: I noticed that the last issue that came out had a strip by Shary Flenniken.

FRIEDMAN: That strip had been in the inventory room for over a year. The former editor, George Barkin, had said it’d run over his dead body. And it didn’t run until he had been dismissed. He didn’t die, but the thing did run. They ran it because they didn’t want to buy new strips anymore, ’cause they’re not paying people.

KELLY: Are they keeping the name alive in the hopes of putting out another movie, or something?

FRIEDMAN: I think that’s all it comes down to. They want to keep the name out there. They own the name, but I think it’s some tricky business where someone else owns the movie rights. I really don’t know the intricacies involved. I never got involved in that. My only interests were bringing in some good cartoonists to the magazine. I did that at the beginning, but it didn’t really work out.

KELLY: Are there other places that you’re looking to get into?

FRIEDMAN: I’m never looking to get into anyplace. Usually, the work comes to me. I guess I’m fortunate. It usually is just a phone call that leads to getting work. Besides the cartoon for SPY, I’m also contributing on a fairly regular basis to Mother Jones right now. And if Lampoon continues doing issues. I guess my comics will still be in there. I’m in the current issue, but it’s hard to say. A lot of the work I’m doing now is for Topps. It keeps me real busy.

KELLY: Why don’t you explain the projects you’re working on for Topps right now?

FRIEDMAN: The reason I wound up at Topps was that Art Spiegelman was there, and Mark Newgarden was there in the Development Department. There’s always been a history at Topps of bringing in interesting artists — like Jack Davis, Wally Wood, Basil Wolverton, Robert Crumb — to work on projects. Mark invited me out. He had a concept to do a card series called Toxic High. It was a parody of a high school series. He decided that I would be the right guy to do all the yearbook faces. We started kicking around ideas, and that led to me doing some pencils for the main scenes in the cards. There were 60 high school scenes and over 100 yearbook faces. I wound up penciling all the artwork of all the main scenes and inking all the faces. They were sent out and painted by John Pound, and a guy named XNO, Tomas Bunk and a couple of other guys. Mark and I wrote the whole series ourselves, with the help of John Marino and Jordan Bochanis. In the writing of Toxic High, we obviously went too far with the violence and bloodletting. We were encouraged to go too far, and we did. When Toxic High finally came out. which was just recently, it was seriously toned down and edited. It didn’t come out the way we intended it to. We were happy when it finally came out. In between working on Toxic High and it finally coming out a couple of years later, I also worked on a lot of different projects. The Barfo Family…

KELLY: What was that?

FRIEDMAN: It’s like a little accordion container filled with this horrible jelly-like candy. You squeeze the little accordion body and vomit candy comes out of the little sculpted head that I designed. I think it became a popular item, although it was nearly impossible to find. It got written up in Time and Esquire and other places. It became a big cult item. It was everybody’s favorite toy that nobody ever saw. Doing work at Topps is sort of like a dream come true. I grew up with that Topps stuff — the monster cards from the ’60s and the Wacky Packages. When I was a kid, I wondered who the guys were that did this stuff for a living… “It must be such a great job to draw that stuff.” And finally, I actually do it... I really enjoy doing work for Topps. It’s relaxing because I don’t have to do the inking process like I do with the comics. It’s mostly pencil work. When I ink a comic strip, the pencil work might not be as detailed as what the Topps work looks like, but it looks almost like the finished piece. I think Mark and I have a great working relationship. We have a similar sense of humor, and we enjoy a lot of the same type of things. It’s a lot of fun to work with him on that stuff.

KELLY: What are some of the other Topps projects you’re working on?

FRIEDMAN: It’s always hard to say what’s coming because Topps has a weird release schedule. It’ll hold onto things. It’s hesitant in releasing certain projects, because they won’t think that it’s the right time for it, for whatever reason. Maybe because it’s a conservative age we live in, but they’re a little nervous these days about releasing some of this stuff that we’ve worked on. Like America’s Ugliest, which is this series of 64 of the ugliest faces that I could possibly have drawn, with the American flag behind each one. [Laughter.] I think they’re a little nervous about releasing that. The flag thing might be the major reservation.

KELLY: Is it the PC thing of dumping on the ugly?

FRIEDMAN: That could be, as well. With Toxic High, Topps was very nervous about the PTA groups coming down on them. And now they’re hesitant about releasing some of the nastier stuff, because they feel that a lot of the big toy chains and stores won’t take the stuff anymore. They really want to play it safe.

KELLY: Also, kids are shooting themselves all the time in schools…

FRIEDMAN: There’s that, too. I can see why a lot of the Toxic High drawings were toned down. It seemed like every day we were working on it, there were teen suicides and hangings and shootings and gunplay in schools. That was the basic theme of Toxic High originally — violence in schools done humorously. It was heavily censored. I’m still pretty happy with the results. The only thing I’m not thrilled about is that it’s hard to find, especially on the East Coast. I had this vision, when it came out, that it would be in every candy store. But it hasn’t worked out that way. I’m still hoping that it’s going to hit stores in a big way. It’s out of my department. I have to move on to the next project. I get calls all the time saying, “Where can I find Toxic High?” I don’t know. You can call Topps and ask them where it’s supposed to be. They tested it with groups of kids behind glass. They watched the kids’ reactions. The kids went nuts for it. I assumed it was going to come out and be some kind of fad. But if you can’t find it, it’s not going to be big.

KELLY: You’re also doing a series of wanted posters for Topps…

FRIEDMAN: Yeah. Once again, they had been originally done about 25 years ago by people like Jack Davis and Wally Wood. We’re updating that. Wanted posters for kids… like babysitters and butchers. The butcher in the butcher shop with human limbs and heads and skulls behind glass, and him standing there with a knife. It’s sort of inspired by EC comics. It’s stuff that I’d like if I was a kid. That’s part of the fun of working with Topps. “What would I like if I were a kid?’’ In a lot of ways, I’m still like that. I still like a lot of the same things I liked when I was kid. Also, they pay well. That’s another highlight.

DRAWING THE FRIEDMAN WAY

KELLY: Your style is different from just about any other cartoonist that’s out there right now. It’s also a style that is sort of an old illustrator’s style. It goes back to the engraved political cartoons of the past that were really labor intensive. Are you influenced at all by those old masters?

FRIEDMAN: No. Not at all. I know it exists, I’ve seen a lot of it, but it has had absolutely no influence whatsoever. I can probably count my cartoonist influences on one hand. But then again, maybe I’m kidding myself; maybe there are a lot of people who have subconsciously influenced me that I’m not even remembering. I just sort of stumbled onto the way I draw. I always liked to draw details: detailed faces especially. And I just found that the way to do that, for me, was to draw in that dot style. But it wasn’t influenced by any particular artist. I really wasn’t aware of anybody drawing that way before I started doing it.

KELLY: It’s something that you came up with on your own?

FRIEDMAN: I don’t know. Obviously I didn’t invent it, because other people have drawn in stipple style — like Virgil Finlay, who was a science fiction illustrator. Art Spiegelman gave me a big file of his work a couple of years ago, and I looked through it: pretty intense stippling and detail, cross-hatching. I guess some people would see similarities with my work. There are no influences for the exact way that I draw. It was something that I felt comfortable with early on. The first time I used it was on the “Andy Griffith” comic, which was the first comic I did; it wasn’t like I was drawing bats when I was a kid or obsessed with George Seurat or anything like that. I used it on the “Griffith” comic because I wanted to draw the characters in detail. Some people can’t believe it when I say this, but I really don’t like stipple drawing; that kind of artwork really doesn’t appeal to me at all. When I see other people who draw that way, it really puts me off. Most people who draw in that stipple style use it to draw curtains, or sand, or clouds, or beaches — things like that. I guess that style makes sense for that kind of illustration work, but it puts me off. The intention early on was to make my work look photographic. Hopefully the comics Josh and I did — and my work in general — look disturbingly real. Early on it was important for it to look real because it was dealing with real people. It was taking all these icons that we knew growing up, on movies and TV, and putting them in different situations. The intention was, hopefully, to disturb people into thinking that this was an actual document of this person’s life. There have been people who actually thought that I had just redrawn photographs because of the fact that a lot of the stuff is just really realistic looking. That was important for the kind of comics we were doing then, and I’m still doing. But I think little by little I got more interested in distorting the realistic artwork and giving it more of a nightmarish feeling. I basically think of myself as a cartoonist rather than an illustrator — the cartoonier, the better.

KELLY: What if you had happened to draw the Andy Griffith strip in a different style?

FRIEDMAN: It might not have worked. I don’t know, I can’t really say… I don’t think it would have had the same disturbing feeling if I had drawn it cartoony. If somebody else had drawn it, it would have been a cartoony spin on The Andy Griffith Show instead of a presentation of the show with something that you’d never see on the show in comic strip form. Sort of like making a little movie with Andy Griffith and all of the other actors lynching a Black guy. Something that would never happen but could happen in a comic strip.

KELLY: It could have happened in the time and place that the show was set in.

FRIEDMAN: If that show was a real representation of the Deep South in the early ’60s, and a Black man had come to town, that might have happened. But I don’t recall a Black man ever appearing on that show. Later on, around 1968, there was a Black woman in the background at one time. And there was a Black gym teacher around then; Opie’s gym teacher was a light-skinned Black in one episode.

KELLY: Is his race ever an issue on the show?

FRIEDMAN: I don’t believe so, no. But anyways. Hopefully the strips — especially the early ones, the life stories — were drawn as realistically as possible. But then again, if you look at the Joe Franklin story I did, there’s a lot of cartoony images. Just mixing up a lot of things — I did that stuff in my early 20s. I was experimenting a lot.

KELLY: Mark Newgarden says that he thinks the funniest stuff you’ve ever done to this day are the one-panel gag cartoons for Kurtzman’s class.

FRIEDMAN: Yeah, those were just throw-away gags. I’m glad Mark likes them. I don’t use them in my portfolio. Though speaking of Mark Newgarden, I think he has one of the great comic minds of our time. He’s one of the funniest humans I’ve ever encountered.

KELLY: Your stuff is obviously labor-intensive, but what is the timeframe of actually completing a one-page strip?

FRIEDMAN: It depends. It depends on whether there’s a deadline, or on what the money is — usually what the deadline is. If I’m doing a strip for RAW, I usually know I have at least six months to get it in. I know that they’re going to be putting together the new issue within the next year or so. Usually, my working process for a comic strip is one panel per day.

KELLY: Pencils?

FRIEDMAN: The entire panel, pencils and inks. I usually work one panel at a time. It’s an eight-panel comic page, so it’ll take seven or eight days. I can work quicker; I just did this comic strip for Mother Jones and it took me three days to do it. An entire page. They pay well, so I was more inclined to work quickly. Again, in the old days I used to spend maybe up to two weeks on a strip for Weirdo, which would pay 50 bucks. So, I was never really in it for the money, although I make a living doing it now. Some of the jobs pay very well, but it’s mostly the illustration work that pays well. You can’t make much of a living doing comics unless you hook up with one of the newspaper syndicates, I guess. Obviously the way I draw is time-consuming; that’s why nobody else draws that way. You have to be a little crazy to do it. You have to be willing to put a lot of time into doing it.

KELLY: I think a lot of people would be surprised to learn that your stuff is done at size.

FRIEDMAN: I used to work larger and it would get shrunk down and I would have all sorts of problems; the stuff would wind up looking muddy, too dark, too light. I really don’t like to leave it up to art directors to reduce it to size; I like to just give it to them at the right size and just tell them to print it as is. “Do a line shot,’’ which is the best way to shoot my work. I usually have no problems. But I’ve had some horrible problems over the years, where stuff gets way too dark and looks horrible. If you look at the book The New Comics Anthology, which came out last year from Collier Books, the four pages I have are totally washed out. It was a really big disappointment. The whole book was a big mistake. Bob Callahan, who edited it, had good intentions. I met with him, and he seemed to know what he was doing, but I think he put too much trust in the publisher, and they really fucked it up. That’s an example of my work looking like shit. I’ve had a lot of problems like that. But all it takes is a little time and effort on the part of the art director to get it right, and usually there’s no problem. Now I just really play it safe and work at size.

KELLY: What kind of tools do you use?

FRIEDMAN: Just a simple crow quill pen. A Hunt pen, number four, I think. The smallest point they make. And black Pelikan ink. I use a Rapidograph to do straight lines and in templates for word balloons. I used a real fine Rapidograph pen to do the “Andy Griffith” comic, but I wasn’t comfortable with it. You get the same line all the time, you can’t vary the thickness.

KELLY: No magnifying glass?

FRIEDMAN: Occasionally. I have one. My eyesight is pretty good; I’m the only one in my family who doesn’t need glasses. Both my brothers and my parents wear glasses. I think that the kind of work I have done has actually strengthened my eyesight. But maybe I’m just kidding myself; Robert Crumb used to warn me to take care of my eyes or I was going to regret it.

KELLY: I would think that you'd be worried about your eyesight because your work is so pinpoint and fine.

FRIEDMAN: It’s not a concern, because I’m 33 now, and my eyesight is still good. But we’ll see. I guess there are other occupations I can think about if my eyesight goes, but I don’t know what they are. I don’t work as intensely as I used to. I can relax a little more now.

KELLY: ls that because you’re getting more money to do what you’re doing?

FRIEDMAN: That’s been the most part, yeah. I pay a mortgage now, so I want to make sure that there’s money coming in. Since I did the Topps work — which doesn’t involve inking; it’s mostly pencil work — I can pick and choose a little more as far as comics and illustration work goes. I’m just lucky that I can still say that I do exactly what I want to do. The only minor compromises I make are the SPY drawings. But it’s fun to be in SPY, especially when they were doing well in the ’80s and everyone seemed to be looking at it. I’m just lucky that I can pick and choose what I want to do: it’s a lot of fun to sometimes turn down art directors when they call. I still get pleasure out of that. I’m a cocky bastard.

KELLY: Do you do a lot of early breakdowns with your strips, as far as planning where your figures are going to be placed?

FRIEDMAN: I suppose. I’ll rough it out on tracing paper first, then do a quick drawing on the actual illustration board. And then I’ll lay out a real tight pencil that I’ll finally ink. It’s not a huge amount of preparation; it’s basically putting down the images. There’s nothing that complicated about it. I’ll break down the whole page, but in really rough form. But then, as far as doing the panels, it’s just one panel at a time.

KELLY: Are you using photo references much these days?

FRIEDMAN: Yes and no. Obviously, for the celebrity stuff I have to use photos, because the likeness is important. For SPY magazine, they send me photographs every month. They have a huge photo library. For some other stuff, I don’t have to rely on it as much, after years of drawing the type of backgrounds that I do — background people, hands, clothing, doors, buildings and stuff — I don’t need as much reference as I once did. I can draw some of the old ugly-guy faces basically without reference. But I still like to keep some, to refer to in case I get a little lost, for shadowing purposes. When you draw in that stipple style, with the shading you can just start from scratch. You just start doing the dot process, and it just starts building up and looking photographic: the textures and the shades, the light and dark, from nothing, without any photographic reference. Even if you started from nothing, it gives it that photographic look. I’ve just gotten good at doing the drawing and making it look like it came from a photograph. A lot of the Topps work was not from references. For the drawing of Dad on the toilet, the only reference I had was this guy’s face — the rest of it was freehand. It’s cartoony but it still has that photographic feel to it. For this one, I had photo reference on his face and her face and this door, and the rest of it was basically freehand — the bodies and the pizza boxes. Just from years of drawing this stuff, I can make it look realistic — for the Topps stuff, half-cartoony and half-real.

KELLY: Do you enjoy drawing background stuff? Walls, furniture, things like that?

FRIEDMAN: Yeah, maybe even more than faces. It’s not what people are zeroing in on. They’re usually looking at the faces in the foreground. When I watch old movies, I’m more interested in what’s going on in the background. In a lot of films and TV shows, I’m more interested in looking at the background characters, or the scenery — hopefully I can see a camera back there, or some wires, some film props lost in the background. To me, that’s more interesting. Just like character actors and grade-Z actors are more interesting than movie stars. So, I guess the way to sum up a lot of my comics is to say that I’m more interested in Joey Heatherton’s toilet habits than her singing onstage in Las Vegas. I’d rather draw Frank Sinatra, Jr. in the bathroom clipping his toenails than belting out a number. He’s not a good example, because I indeed enjoy his singing. In any venue. [Laughter.]

KELLY: Have you seen him live?

FRIEDMAN: No. I’d like to, but now he just conducts for his father’s big concerts. His pop helps him out.

KELLY: Do you sneak friends’ faces into the backgrounds?

FRIEDMAN: Yeah. Especially in the Topps work. And the comics as well. Faces would pop up from time to time. That sort of came from the Marnin Rosenberg comics that Josh and I did.

KELLY: This is a friend of yours?

FRIEDMAN: Yeah, an old friend from Great Neck, Long Island, who we sort of grew up with. We did a couple of strips about him; one where he’s trying to date women, the other where he works in the carpet store. He’s a real likeable, good guy who has had his problems, so we just decided to poke fun at him in these two strips. They were based on long conversations that Josh would have with him on the phone, so for the most part they were based on reality.

KELLY: You mean that actress moved in with him?

FRIEDMAN: Morgan Fairchild? No, that was for the most part fiction. But the comic where he’s hooked up with a computer dating service is all true, except for the very end when he finally goes to a woman’s house and she turns out to be a hellish monster. The rest of it is all based on truth, embellished a bit. And also, the strip where he works in a carpet store in Queens. That’s also based on true conversations with Marnin.

KELLY: What does he think of the strips?

FRIEDMAN: They appeared in National Lampoon, so they got a lot of attention where he lives in Great Neck. He would walk into his local candy store and they would recognize him and congratulate him. I don’t know if it helped his sex life at all, appearing as a comic strip character in Friedman brothers comics. I think he was pleased with them; he wound up buying the Morgan Fairchild one from us. He liked the attention. There wasn’t that much going on in his life, so he was finally just looking forward to these comics appearing. He would actually call us and say, “When are you going to do some more about me? That’s about all I have to look forward to.”

KELLY: You’re doing fewer strips lately than you have been in the past.

FRIEDMAN: I was doing a lot last year, in ’91, only because I had a contract for a monthly strip for Details and a monthly strip for the Lampoon. I was doing, on average, two strips per month, which is a lot for me. I quit Details, and the Lampoon thing is behind me now, so I’m doing more illustration work and more work for Topps, and I’ll occasionally do a strip. I did two strips for Mother Jones recently, and I did a strip that was intended for Details and wound up in the Lampoon. I collaborated with my wife: it was sort of a parody of Ripley’s Believe It or Not. It’s in the current issue, the one with the awful Mike Tyson — I mean that wonderful Mike Tyson — cover.

KELLY: How’s working with your wife?