The graphic novel boom of ten years ago coincided with the bottom dropping out of the publishing industry and lifted the fortunes of too few cartoonists. Working on a graphic novel for three years with only a $10,000 advance (if that much) is not going to work. As a teacher I try to fully support my student’s artistic and career ambitions but at the same time I have a responsibility to help prepare them for the reality of the marketplace.

The graphic novel boom of ten years ago coincided with the bottom dropping out of the publishing industry and lifted the fortunes of too few cartoonists. Working on a graphic novel for three years with only a $10,000 advance (if that much) is not going to work. As a teacher I try to fully support my student’s artistic and career ambitions but at the same time I have a responsibility to help prepare them for the reality of the marketplace.

So what’s a cartoonist to do? One positive sign is that comics are quickly branching out into other fields like education/visual literacy, graphic medicine, comics journalism, and graphic facilitation. Last summer, Marek Bennett and I created a comic, The World is Made of Cheese, The Applied Cartooning Manifesto that grew out of conversations we were having about forging a life in comics beyond the traditional publishing model. I always admired Marek’s cartooning career because he has done just that.

“Applied Cartooning” is jargon to be sure, but I hope it can become useful jargon. The idea is to better position cartoonists in the marketplace so our expertise is recognized and we are compensated more fairly for the skills we bring to the table.

Marek and I asked five cartoonists to talk about this notion of “applied cartooning” and how they are making ends meet while also doing work that feels meaningful. Suzy Becker already has an impressive résumé; Jess Ruliffson, José-Luis Olivares, Andy Warner, and Mellanie Gillman are earlier in their careers. Like Suzy they are talented, smart, and tenacious. Marek facilitated the conversation.

—James Sturm

Jess Ruliffson

MB: Let's talk about your comics based on veterans' stories – how did that work come about?

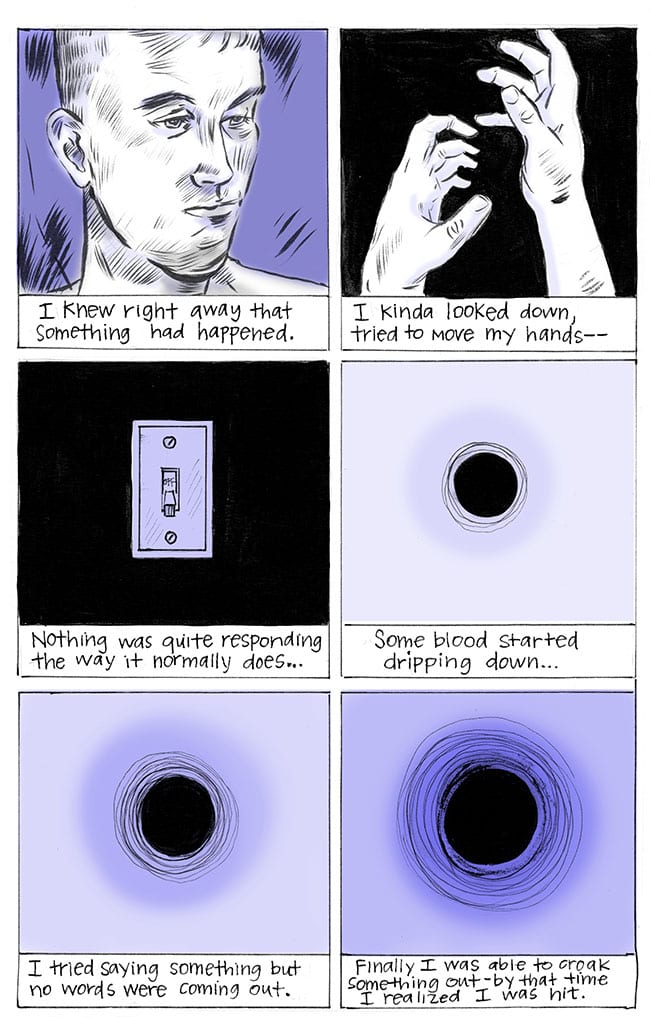

JR: I first read Sebastian Junger's War and saw his and Tim Hetherington's documentary, Restrepo. Seeing journalism that sought to offer a realistic portrait of the day-to-day of war totally blew my mind. Shortly after I discovered Tim's work, he was killed in Libya during a mortar attack. It got me thinking about what kind of impact my work would make after I was gone. I had always wanted to make comics, but making comics (and art in general) is so isolating. I wanted a chance to engage with other people. I also wasn't convinced of my writing ability and didn't want to write a whiny memoir in my mid twenties. I am part of the generation we sent over to fight in Iraq and Afghanistan. I decided to go to art school, and they decided to join the armed forces and fight in the wars.

I wondered why that was, and what they were going to do when they got back home. How does war shape your identity, especially when you join at such a young age? Even if you don't have combat experience, you're told how to dress, when to eat, and then when you get out, you have to start from scratch. And the military doesn't seem to be very good and helping soldiers transition into civilian life.

I wanted to report that story so veterans would feel less alienated, and civilians would understand them better. In narrowing my focus to a specific story, it actually opens the world up wider, by connecting me and my collaborators with an audience of people who are engaged with the topics discussed in the comics we've made. Not that we have a huge audience, but the quality of that audience is meaningful to veterans and myself. Any real connection made is so exciting and worthwhile, and usually leads to other opportunities to get these stories out there.

MB: How does this work connect your comics practice with wider communities?

JR: I've gotten to know a lot of incredibly talented veterans, writers, and cartoonists through this one project (Invisible Wounds), and it's still developing even now. Working with storytellers and veterans creates a level of accountability I wouldn't have in working alone. A lot of civilians are interested in helping veterans and the comics project is interesting to them, so I get a lot of positive exposure I know I wouldn't have if I was just doing my own thing in my corner of the universe. It's also really good for me mentally to engage with other people and feel like I'm making a positive impact on society.

MB: How does that affect you, as an artist?

JR: I feel like my work has a purpose and that it can help other people. Considering the impact of my work in larger terms (rather than just how much I'll be paid, or if people will like it or not) has made me a better artist and a better human being.

I've been working on collecting interviews from Iraq and Afghanistan vets and compiling them into a larger book, currently self publishing each story as a mini comic, and also publishing the stories in magazines and digital outlets to generate interest and cultivate an audience – and make a little money, too (Oxford American, Symbolia Magazine, and Wilson Quarterly, most recently).

Andy Warner

MB: How would you describe your applied cartooning work?

AW: As a comics journalist, my focus is pretty wide and restless. I've done comics about everything from the shattering of the Iraqi state this summer to stories about the moonshining culture on the bases of Saudi Aramco in the 1980s. I did a piece about the largest military base that the US ever closed on home soil, and the effect that closure continues to have 20 years later.

MB: What’s the response been like to the pieces?

AW: I was interviewed about the Saudi Aramco piece for the Monterey Herald, and it was picked up by Upworthy, which always increases the visibility of a project a bazillion times. There was a pretty big response within the local community, too. The comic was featured by CSU: Monterey Bay (the college I talked about in the piece), and on the Facebook pages of some of the towns I mentioned. Response was overwhelmingly positive.

MB: What's your favorite part of this work?

AW: One of the biggest joys of projects like these is that, in addition to the cartooning being fun, the reporting itself is really interesting. Getting to go to Fort Ord and tour around it, especially in areas that are off-limits to civilians (journalistic privilege!) was really interesting. For other pieces that I've done, I've had the opportunity to talk to scientists and artists I really respect, or spend a week knee-deep in research. It's very gratifying.

MB: So how do you find work in this field?

AW: Most of the time, my pieces are entirely self-directed. I'll pitch something to an editor that I think will like it, and they'll bite. There are a few exceptions over the past year that would also be especially relevant to the idea of "applied cartooning."

First is a series of educational comics I did for KQED last fall through the spring, that explored the "math of news" in a way that could be integrated into a classroom setting. I did 11 comics in the series, on everything from California water policy to the history of the Voting Rights Act, and worked with my editor to figure out the topics, rather than pitch them myself. It was funded by a grant specifically aimed at producing content for teachers to use to engage their students as consumers of news, and I've actually received quite a few emails from teachers telling me that they hang print outs of the comics in their classroom and use them in their lesson plans. Apparently one comic on income inequality was even somehow integrated into a school play, although I have no idea how!

The two projects that that veer more away from journalism, but still use the skills I developed in that profession. One was a piece for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency about Palestinian refugees of the Syrian Civil War, and the other was a piece for the Center for Constitutional Rights about a radical American evangelical pastor who helped create the anti-gay laws in Uganda and is being sued in US courts for persecution. Both of these projects were paid for by organizations mentioned in the pieces, rather than a media outlet, so I would consider them advocacy work, rather than reportage. That said, I would not have taken the work had it violated my ethics, and I created the pieces using the same journalistic principles I apply in my other work.

I was also very clear in my promotion of the pieces that they were made possible because of funding from those organizations. From what I've heard, both pieces were quite successful as lynchpins in awareness campaigns that UNRWA and CCR were organizing.

I've been approached by other organizations to do similar work, but not taken the job. For me, doing work like that is entirely dependent on the context and the organization paying for it - although if I choose not to take work, I always make sure to pass it on to others in case they feel differently. Cartoonists gotta eat, after all.

José-Luis Olivares

MB: So... have you read the Applied Cartooning Manifesto?

JLO: I find it very inspiring! I chased the dream of being a "rich beloved genius cartoonist" a bit too long and felt like a failure. But luckily I've had one foot in reality. I took jobs related to publishing, education, and design.

I now work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the News Office, where I'm like an in-house creative person. It's a pretty diverse job: I photograph researchers and their projects around campus, help with video shoots, select images for news stories, and (my favorite part) create illustrations when it's necessary.

MB: How does this work connect your comics practice with the wider world?

JLO: Some of my illustrations are collaborations with the researchers and writers, who have a specific process they want to represent. For example, in my images provided, the top two were collaborations. The left is a 'probabilistic graphical model' of how an algorithm collects data quickly. It's a confusing concept, but the researchers imagined it as if someone injects blue dye into, like, a pachinko machine, and then watches where the concentration of blue goes. The other image is about a new type of osmosis using two types of water that can generate even more power. The researcher had lots of suggestions, such as which way the water needs to flow, and said the sifting device reminded him of paper-towel textures. Of course, I scanned a paper towel to get the correct texture.

MB: How do your comics skills inform your other work?

JLO: I know my obsession with comics and design helps me tremendously at my job. Making comics is all about visual communication, and it's lovely to stretch these skills in new ways. It's really great to see my work online, on screens across campus, and shared across many science news sites. I'm thrilled that my work is seen by people, that I have deadlines, and that I feel a sense of community with my colleagues.

Suzy Becker

MB: What does “applied cartooning” look like, in your work?

SB: One example would be a whiteboard animation I co-wrote and illustrated for the non-profit What Kids Can Do (WKCD): “How Youth Learn.”

Some high school students cast themselves as parts of the brain in a skit demonstrating how what cognitive scientists know about adolescent brain development could play out in the classroom. The skit was well received at a national teachers' conference and WKCD sought and received funding to make the skit into a video. At 25 minutes, the skit was too long. The students and WKCD were familiar with my cartoons (which have been a graphic voice for the Coalition of Essential Schools and student-inquiry-based learning) and asked if I would consider making a whiteboard animation based on their skit for a rock-bottom fee. I said yes. It met my criteria – It represented an opportunity to truly collaborate (on something) fun, meaningful, and creative. And I'd always wanted to do a whiteboard animation... (so it was) a paid learning opportunity.

The students then took the summer off and I wrote the script with a WKCD representative. We talked Fablevision (Peter Reynolds's production company who I'd also always wanted to work with) into a rock-bottom fee, and we shot the thing in a grueling day with the original students on site and two students from a performing arts school in New York City who provided voiceovers. WKCD and the grantmaker distributed it widely to the field. (I didn't because I was sure it stunk until the positive reviews started coming in from places like MacNeil/Lehrer and Sesame Workshop.)

MB: How does all this connect your comics practice with the wider world?

SB: It connects science and education scholarship with teachers, students, and parents. The video is shown at conferences, in-service days, faculty meeting, parent meetings, classrooms and it's been watched by over 30,000 people (and a few aliens) on YouTube.

MB: How does it affect your practice, your career, and your community?

SB: I've had a lifelong struggle with what sometimes seem like dueling passions-- wanting to make people laugh and wanting to make a difference. I know that just making people laugh is making something of a difference but I find it most satisfying (generally least remunerative) when I'm doing both. This also got my work in front of, well, Macneil Lehrer and the Sesame Workshop, (resulting in) an invitation to a short film festival, and a handful of calls about similar projects. I like the depth it adds to my "portfolio," although most publishers would have preferred I spent the same amount of time focusing (not fuzzying) my brand.

I loved the CCS manifesto – I feel extremely lucky (on the days I feel extremely lucky and my bills are paid) that I have been self-employed for all but the first eighteen months of my career and I have very seldom had to draw a line between my personal work and my other work. I totally believe in comics living outside the box. We are masters of graphic shorthand, telegraphing messages (in) times characterized by increasing busy-ness and decreasing attention spans.

MB: Tell us about your work.

MG: My biggest project currently is the webcomic I've been working on for 3ish years, As the Crow Flies. It's a fictional story about a small group of queer and trans teens that meet during a Christian youth backpacking camp somewhere in the middle of the Rockies. (It was an Eisner nominee in the webcomics/digital category this year, too, which was pretty cool!)

The project came about in part from a nonfiction inspiration: my own experiences growing up as a queer, nonbinary teen in a not-very-queer-friendly Christian environment, and my own growing interest as an adult in how intersectional identities played a role in homogenous religious spaces and feminist spaces. I was concerned about how few comics actually addressed intersectional issues like these in a head-on way, even though they're part of the lived experience of so many different people.

MB: How does this work inform your publishing model?

MG: Given its subject matter, choosing to publish the comic as a webcomic seemed like by far the best choice. It's always been important to me that the story be accessible to the people most likely to relate to it – i.e., young queer/trans people and people of color. Young marginalized people can also be among those least likely to have economic access to things like expensive, full-color graphic novels or a long chain of serialized floppies. Making the comic available for free online was the best solution I could find for making it accessible to more than just the usual affluent/white/cishet comics readership.

It's worth noting, too, that by doing this, I'm also participating in a much wider historical trend of creators from various minorities turning to self-publishing as a platform to tell their stories, having been largely shut out of mainstream publishing venues. While the average graphic novel bookshelf is still overwhelmingly white and cishet, the webcomics medium seems to be becoming increasingly diverse, both in terms of content and the creators it's bringing in. That's an exciting trend, and I'm really looking forward to seeing how it affects the medium as a whole!

MB: What effects do you see this project having on wider communities?

MG: Almost 3 years and a little over 200 pages later, it does seem like the comic is having an effect, but being just one cartoonist working on a solo project, it's not always easy to determine exactly how big an effect. I do get a lot of mail from readers about the comic, which seems to fall into two categories. I hear the most from young queer and trans people, telling me how they connect my work (and the work of the larger community of queer webcartoonists) to their own experiences, and (even better) how it has inspired them to work on telling their own stories, too. That's something I feel like I can never overstate the importance of – if my work can contribute in any small way to there being more room in the comics medium as a whole for queer narratives and queer creators, then I feel like I'll have done my job.

The other category of responses I get I have more complicated feelings about, but it's worth mentioning, too: to my surprise, I do seem to have garnered something of a readership among the groups of people I explicitly wasn't writing the comic for: the straight-cis-white-guy contingent. The responses I get from them fall all over the map, from heartfelt to ignorant to borderline offensive. (The thing I hear by far the most is, "Based on the description, I thought for sure this comic would be too preachy/too social-justicey/I'd hate all the characters/etc., but actually it's pretty good!", which says a helluva lot about the biases these men are bringing to the table – and, I can only hope, the way they've started to question them, too.) I feel weird about trying to predict how much of an effect my work is having on the privileged sectors, but it's interesting to me that these men seem to be sticking with the comic as it grows – it's a part of their reading landscape now, so to speak.

MB: What does all this tell you about applied cartooning, and comics in general, moving forward?

MG:I guess, in sum, fictional works might not be an immediate shoe-in for the applied cartooning medium, but I do think fiction has a significant effect on the world around us. There's still a huge need for both more diverse stories in the comics medium, as well as publishing/job opportunities for more than just the usual privileged creators. I think digital publishing and webcomics has a huge potential to help shake things up in both those areas – and the medium is still so young, we've barely seen what it's capable of yet. As cartoonists and educators, we've got an important task on our hands, being the generation that's first-out-of-the-gate, so to speak, in the digital/webcomics medium – I'm excited to see how it develops over the course of our lifetimes!

JAMES STURM: In the manifesto, Marek and I tried to articulate the distinction between "pure" and "applied" cartooning. Did that make sense to anyone else? Is it a false dichotomy? I consider the comics I've done to promote CCS or to advocate for causes/issues, and even the Applied Cartooning Manifesto itself to be a different animal than the comics I make to "purely" satisfy my own creative needs (which feels more akin to a spiritual practice). These two approaches do feed off each other and sometimes I think my goal as a cartoonist is to have this distinction disappear entirely.

I look at something like Roz Chast’s book, Can We Talk About Something More Pleasant and how—through the combination of her craft and commitment to the material—she has opened up a conversation about the difficult issues of caring for aging parents. The book succeeds because it is so personal and honest.

SB: I think it makes more sense as a continuum rather than a dichotomy – or maybe I'm being narrow in my view of dichotomies, and they are in fact the origins of continua... For me, the objective is the most important thing.

Say I really want to make middle school engaging because I believe lifelong curiosity (Andy's mention of curiosity resonated with me) and a sense of agency (among other things) can be sparked (or extinguished) by education. How can I do something about that? I can help start a secondary school. I can do a whiteboard animation. I can...

Or say it's 1986. What can I do about the overwhelming fear, despair about HIV/AIDS? I can start a bike-a-thon. I can mobilize my network of greeting card company accounts, suppliers, consumers, etc. to help me increase awareness, compassion. I can create graphics for a t-shirt, informational brochure. I can...

Or say there's a community development organization in San Francisco which invites a different cartoonist each year to create a logo and strip for a high profile annual fundraising event, involving bus and billboard advertising in metro SF. I think it's a worthwhile cause, but I'm not local/passionate about it, so I will allow them to select use my work and approve the final use, but not invest a ton of time.

I totally share your ideal James, and since I usually own the objective, I feel lucky, like I am often working in that ideal realm. Anyhow, I am best known for and make a living from my books, (not the projects I have previously discussed), which include two works of creative nonfiction, illustrated memoirs I Had Brain Surgery, What's Your Excuse? and One Good Egg. My motivation to write/illustrate them is actually the same basic motivation I have to communicate with my writing/art at any level – to say we are not alone. Not nearly as widely read as Roz Chast's, nor as beautifully drawn as Melanie's, they have still succeeded in opening up conversations about difficult (and lonely) experiences: brain injury and fertility. (Being both gay and brain-injured, I can say with some authority, brain-injured people – numbering in the millions, not to mention the 20% of veterans coming home with brain injuries – are more closeted than LGBT people these days.) While there are things I will not write about, I generally believe the most personal communication is the most universal. The same belief made my first book All I Need to Know I Learned from My Cat, an international bestseller. So again, I agree with James- the most personal, honest accounts are the most winning. I would also include Jess's unwavering, heart-rending accounts among them.

JO: I really relate to James' description of "Pure" cartooning as a spiritual practice— it's the art you have to do to stay sane and happy. "Applied" cartooning is like, "what do I have to do to pay the bills?"

I also want to find the perfect balance between these polar opposites. I think a big factor in this is the economy and job opportunities. I'd say editorial cartooning is one historical example of Applied Cartooning. But what about newspaper comic strips, are they pure or applied? Some newspaper cartoonists created amazing art, but they had to do so by adhering to limitations — what audiences and newspaper editors wanted. Probably, the history of cartooning has always involved cartoonists finding a good balance between the Pure and Applied. Maybe "applied cartooning" is a necessary response to today's economy: we can't just navel-gaze anymore, we have to interact with the world if we expect anyone to pay attention. Is this the secret formula for making comics people care about? Can we no longer be the stereotypically introverted artists? Do we have to combine all our skills— all our education— to make it work?

SB: I just got finished doing a kick-off assembly for the 5th grade Citizenship Project at the Pine Hill Elementary School in Sherborn, using my Kids Makes it Better book (an anthology of kids' solutions to world problems, and a write-draw in journal – with pages for kids to come up with their own solutions). Kids initially use their imagination to solve a problem. The thing that struck me (aside from the fact that kids, if engaged, are so wonderfully undaunted by these problems) is that kids' imaginary solutions often had real-life applications. (Hence the "This really works!" side bars).

Anyhow, Einstein said how imagination is more powerful than knowledge. He also said (another weak paraphrase...) how we can't often use our existing knowledge to solve our existing problems. Imagination and creativity, sadly, are generally not part of standards-based education. Nor is it tested on MCAS, PARC – the standardized tests. I believe the acquisition of problem-solving skills, especially with parameters (as in applied cartooning) is an arts education's strongest selling point. It's also incumbent on us artists to make art quantifiable, assessable, or gradable. Kids can demonstrate (write, articulate) their process, showing research skills, appropriate selection of media, project management, collaboration, their objectives, etc. – making a seeming epic failure or imperfectly executed project a worthy effort.

JLO: Suzy — It's so cool that you are collaborating with kids and groups. Do you feel like a superhuman? I mean, you must bring all sorts of talents to the table, including being fun to work with and a good communicator. Do you think that's something that can be taught?

SB: I had a roundtable argument with R.L. Stine (Goosebumps, 100K followers on twitter) about whether you can teach humor. I believe the problem (and I do believe it's a problem) is that we don't. That is why our work isn't understood and appropriately valued. (Often it's marginalized, at best viewed as a lucky shot/talent.) There are some who are advocating for STEAM (adding the “A” for arts to the Science + Technology + Engineering + Math = STEM acronym).

MB: So how does the act of drawing comics keep us going, physically, materially, and financially?

JR: I don't have a lot of practical advice for monetizing this work model, but I do know that following stories I'm passionate about has lead to paying jobs. I just finished working on a comic that takes Homer's Odyssey and translates it into the experiences of soldiers returning from Afghanistan. The goal is that this book would be required reading for returning Marines and would help them reintegrate and foster dialogue about PTSD in an authentic way.

SB: I am the main breadwinner in the family, so I more often find myself in a position of having to turn down a worthwhile but low to non-paying project. The bigger challenge is maintaining balance and not depleting myself which results in a mental paralysis, failure to find much funny, and more likelihood to find it all overwhelming. I pretty much burned myself out trying to keep on deadline with the second illustrated novel in my series. Parenting, getting up out of my chair, eating – everything took a backseat. The resulting draft was episodic and not funny enough.

The act of cartooning (which for me is primarily the ideation phase) keeps me going on a very basic existential level. I feel really lucky to walk around the world looking for things that will make people laugh or move them in a positive direction. (I leave the dark, depressing creations to others who find them sustaining. And, I mean that, not sarcastically.) I will tell kids it's like having a superpower, this ability to reframe stuff that's potentially scary, overwhelming, or ugly in a funny way. I lost my sense of humor temporarily (although some Amazon reviews would claim I never had one) after brain surgery. The world was a much scarier place.