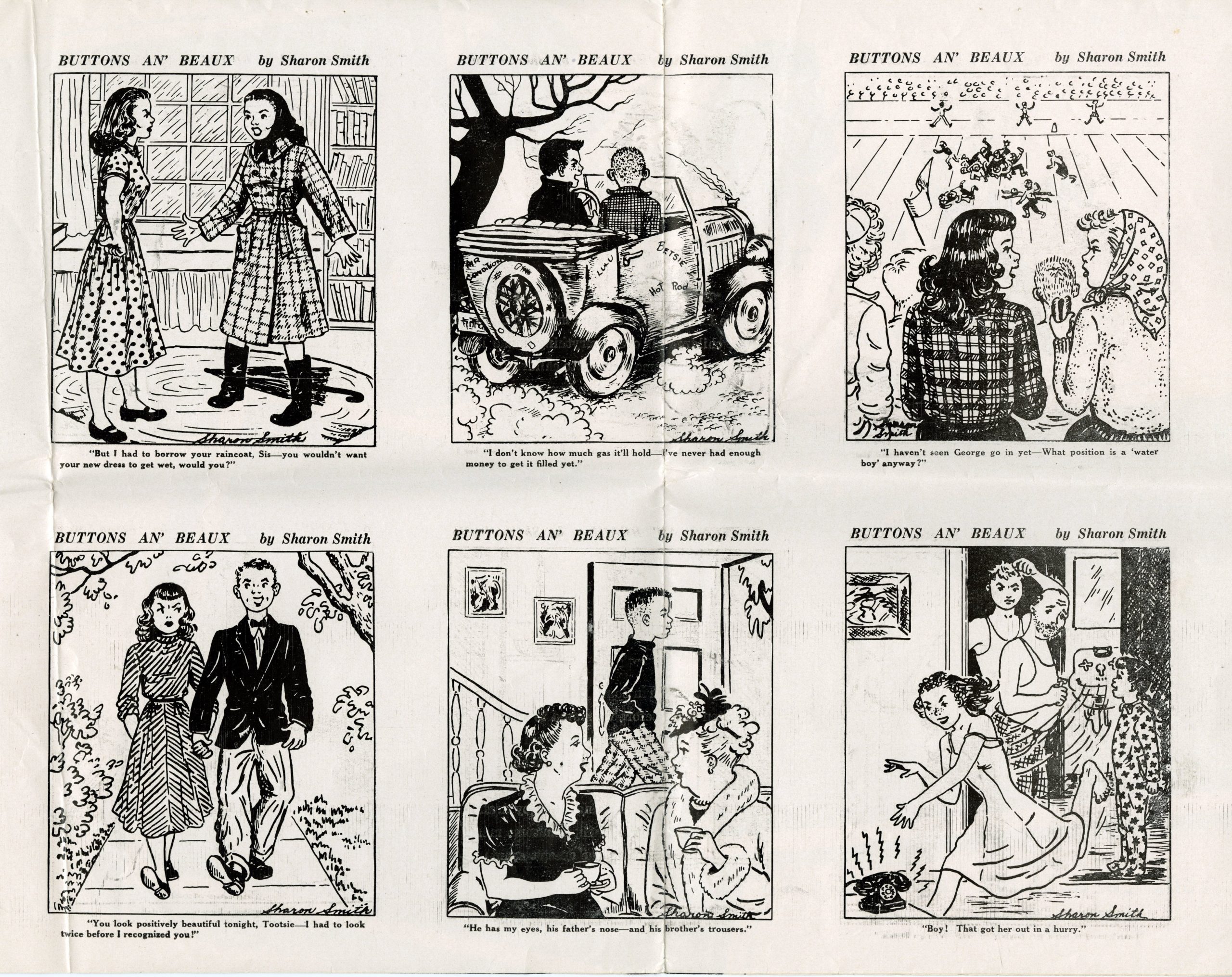

“Ever since I can remember I have been drawing.” -Sharon Smith Kane, Buttons an’ Beaux media kit, 1950

* * *

Children’s book author and cartoonist Sharon Kane (née Smith) passed away on November 3, 2021 at the age of 89. Her newspaper panel Buttons an’ Beaux, launched while she was still in high school, established her as one of the nation’s youngest syndicated cartoonists.

Kane was born into a creative family in South Bend, Indiana, in 1932. Her father, Stuyvesant Smith, was a research engineer for Bendix Aviation whose accomplishments included the invention of the automatic choke for automobiles. Sharon’s mother, Eunice Young Smith, was a voracious reader and gifted artist. Sharon’s older brother, Chadwick, took after their father and studied science.

Artistically inclined from a very young age, Kane first published artwork in Children’s Activities, forerunner to Highlights for Children, before the age of ten. “My mother told me that I began drawing as soon as I could hold a pencil, at two or three years old,” said Kane in a 2014 author profile at Amazon.com. “She, being an artist herself, and a writer, always encouraged my creative inclinations.” Eunice read to her children, inspiring a lifelong love of books, and encouraged their creativity.

By her thirteenth birthday, Kane was a fixture in her local Indiana newspapers as well as national publications including Child Life and The Christian Science Monitor. “Artistically, I was mostly self-taught,” she told me in a 2021 interview. Kane admired classical book illustrators such as Howard Pyle and Elizabeth Shippen Green and dreamed of becoming an illustrator. She also loved reading the Sunday comics in the newspaper, especially Mutt and Jeff.

In 1941, the Smiths moved to their “house on the hill” in the small town of Mishawaka, Indiana, a change in scenery that would provide inspiration for many of the books Kane illustrated later in her career. “In Mishawaka, I became acquainted with farm animals,” Kane recalled. “We had a cow, chickens and pigs. It was a rural life, with hills and woodland and wide open spaces.”

In high school, Kane drew illustrations for her school newspaper, designed posters for school dances and plays, and entered every art contest she could find. She won honors in the state Easter Seals design contest and an honorable mention in the Easter Seals national design contest as well as four Gold Key Awards in the Scholastic Art Contest. She also contributed fashion and advertising illustrations to Indiana’s South Bend Tribune.

During her junior year of high school, Kane’s class elected her editor of the Mishawaka High School student newspaper, the AllTold, for which she penned a humorous teen advice column. At her mother’s suggestion, Kane added illustrations to her articles. Positive reader response led her to create a single-panel cartoon for the AllTold. “[My mother] suggested that I send my early cartoons to the editor of the South Bend Tribune, which I did, and that was the beginning,” recalled Kane. The Tribune published Kane’s cartoons on its teenage page under the title Atomic Teens.

Meanwhile, Kane’s mother Eunice began to pursue her own career as an author and illustrator. “My mother was having her own ‘breakthrough’ at that time,” recalled Kane. “She signed up to enter the American Academy [of Art] in Chicago. There was a train running from South Bend, Indiana to the Chicago Loop and she took it. An act of great bravery at that time, she got to Chicago, found an apartment, and then searched out a job to support herself.” With a small portfolio of her art, Eunice landed a position at Consolidated Publishing, where she drew illustrations for children’s books.

“I took over the housework, laundry and meal preparation along with my dad, and somehow we managed,” said Kane. “Mom would come home on weekends maybe twice a month.” After about six months in Chicago, Eunice decided she had enough experience with the publishing industry to continue her career from home, writing and illustrating her own books. Her children’s book The Jennifer Wish, published by Bobbs-Merrill in 1949, was the first in a series of “Jennifer” books based on Eunice’s early 20th century childhood but starring a protagonist based on Sharon.

During Kane’s senior year of high school, her South Bend Tribune editor, Frederick A. Miller, understandably proud of the Tribune’s teenage cartoonist, reached out to professional cartoonists on her behalf. Several responded with advice on cartooning and suggestions on refining her work for newspaper publication. Miller also took the liberty of submitting Atomic Teens to newspaper syndicates. The McNaught Syndicate, based in New York City, responded positively, and ten weeks after the debut of Atomic Teens, McNaught signed Kane to a syndication contract. She was 17 at the time.

“‘Buttons And Bows’ was a popular song at that time and I took a version of that as the title for my cartoons,” recalled Kane. Her ten-year contract called for her to produce six panels a week. On Monday, May 1, 1950, near the end of Kane’s senior year of high school, Buttons an’ Beaux debuted in ten newspapers nationwide. “The big question was if I could produce six panels a week consistently. It was a big commitment, but also an opportunity,” said Kane. “This was all so timely, as my parents would not have afforded to send me to college, and now, with diligent effort, I could put myself through, which I did.”

Kane attended Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois, where she studied art while maintaining her six-days-a-week publication schedule for Buttons an’ Beaux. In that first year, her initial contract and publication in ten papers earned her $1,500.

“McNaught gave me no guidelines or instructions,” said Kane. “They did want me to give them six or so extra cartoons to use as replacements in case one of my submissions was unacceptable for some reason. Any communications between the editor and me would be by mail.”

At college, Kane found a happy balance between her studies, her career, and her social life. Though she initially majored in art, she developed an interest in psychology, and both art and psychology influenced Buttons an’ Beaux. She also took inspiration from her classmates and college dating life. “Coming up with new ideas was always the challenge,” she recalled in an artist’s statement written in the early 1970s. “I was always alert for something that could be translated into a cartoon. I had a drafting board in my dormitory.”

In her sophomore year, Kane changed her major to psychology. Midway through her junior year, a professor convinced her to transfer to the University of Wisconsin, telling her, “You really want to learn. You should be in a better school than this.” When the university refused to give her credit for three of the graduate courses that she had taken at Bradley, she reluctantly made the decision to change her course of study back to Applied Art. She took summer school classes to keep on track for a spring 1954 graduation.

Circulation on Buttons an’ Beaux had grown to 25 papers, a respectable number, but not enough to sustain a career as a newspaper cartoonist. With the increasing course load at her new school, Kane decided to retire the feature and focus on her studies. A handwritten note on the back of Kane’s final invoice to the McNaught Syndicate—“thought mother was dying—but she didn’t”—may have also played a factor in her decision to finish her degree at the University of Wisconsin, a school much closer to her parents’ home. Kane was—just barely—no longer a teenager when she stepped away from Buttons an’ Beaux, and may have reached a natural stopping point as an artist of teen comics.

“Sharon Smith Kane’s Buttons an’ Beaux may not be as well-known as, say, Archie and his pals in Riverdale, but it captures post-war teenage life with just as keen an eye,” says Karen Green, Curator for Comics and Cartoons at Columbia University’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library. “Its creator depicts bobby-soxer culture from her inside vantage point, chronicling the rising dominance of adolescence in American life, but with a charm and humor beyond her years.”

Amy Lago, Comics Editor at the Washington Post Writer’s Group, admires Kane as a cartoonist, but also as a pioneer in an industry that had few women in creative roles at the time. “Sharon Smith Kane’s humor was sophisticated for a teenager. Her art—linework, inking style, design choices—was sophisticated for a cartoonist of any age or sex,” she says. “How many young readers—or adult readers—in the 1950s assumed [Brenda Starr cartoonist] Dale Messick was a man? One hopes Smith’s use of her own name might have inspired some other girls and young women to pursue art. And humor.”

After her graduation from the University of Wisconsin, Kane worked briefly for a fashion catalog house in Chicago before marrying artist Russell Koester in March 1955. Koester, then a First Lieutenant in the United States Army, was designated for assignment in Seattle, Washington, and the pair lived there for two years. Kane occupied her time with art classes and freelance work, including features for Children’s Activities and design work for children’s programs at the local television station. “I found myself more and more intrigued with children’s book illustration,” she recalled in her 2014 author profile. “I began submitting samples of my artwork to various publishers with encouraging responses from editors but with no actual assignments.”

Unable to get the children’s illustration assignments she wanted, Kane wrote and illustrated a picture book manuscript of her own and sent it to her mother for feedback. Without telling Kane, her mother passed it along to a publisher she knew, Albert Whitman & Company, which accepted it. Where Are You Going Today? was published under the name Sharon Smith Koester in 1957.

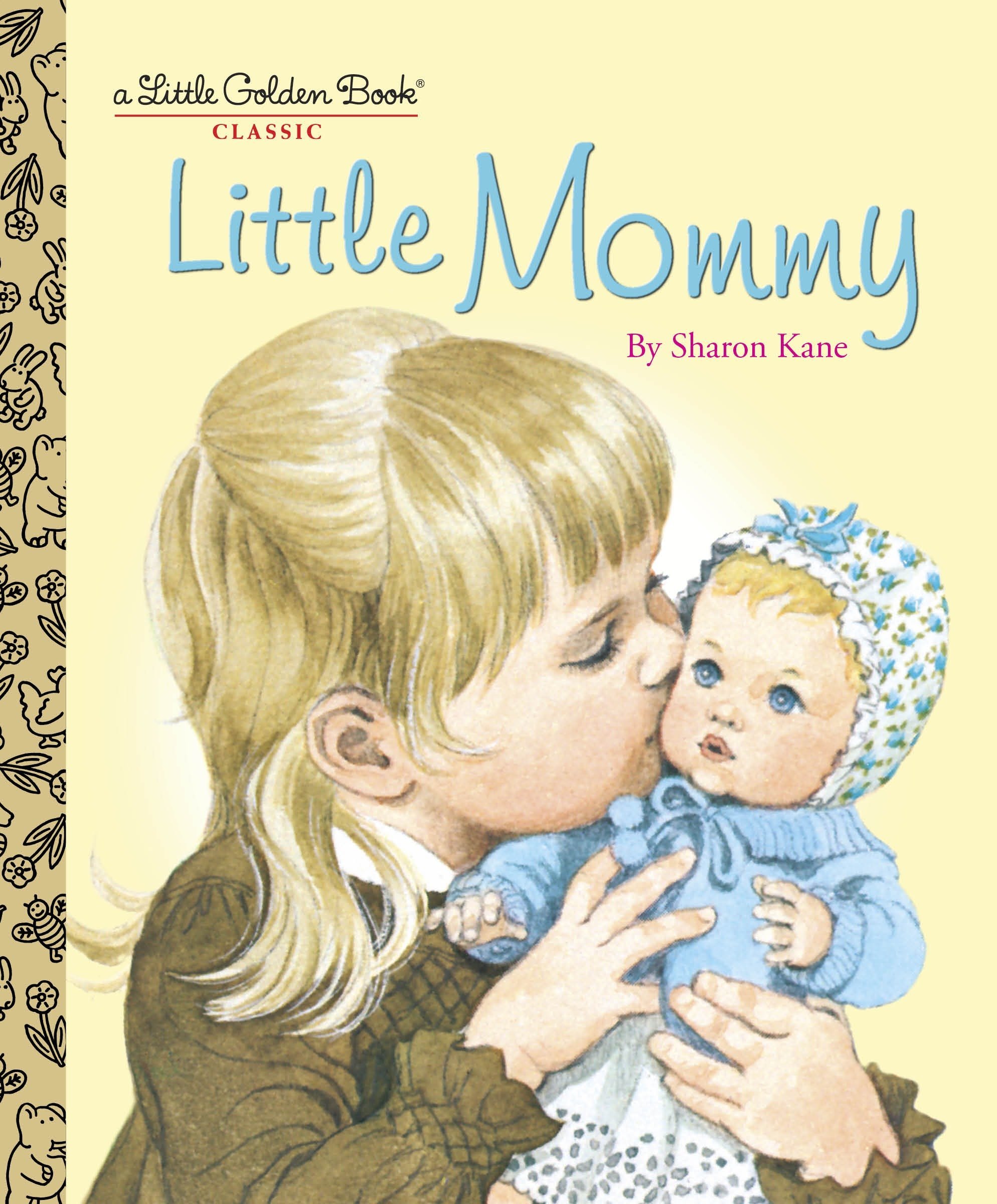

The success of that first book opened the doors at other publishers, including Rand McNally and Golden Press, publishers of Little Golden Books. Kane divorced Russell Koester in 1959 and married artist and noted Hawaiian historian Herb Kāne that same year—tactfully described by Kane as “a rearrangement of her personal life”—and all her subsequent work was published under the name Sharon Smith Kane. Her children Jason and Jennifer were born during this era of her career and provided further inspiration for her art. The prolific artist produced about one children’s book a year through the early 1980s, with her most popular book, Little Mommy, originally published by Golden Press in 1967 and still in print today. She and Herb Kāne divorced in 1974. He and their children relocated to Hawaii, while she remained in Glencoe, Illinois.

The success of that first book opened the doors at other publishers, including Rand McNally and Golden Press, publishers of Little Golden Books. Kane divorced Russell Koester in 1959 and married artist and noted Hawaiian historian Herb Kāne that same year—tactfully described by Kane as “a rearrangement of her personal life”—and all her subsequent work was published under the name Sharon Smith Kane. Her children Jason and Jennifer were born during this era of her career and provided further inspiration for her art. The prolific artist produced about one children’s book a year through the early 1980s, with her most popular book, Little Mommy, originally published by Golden Press in 1967 and still in print today. She and Herb Kāne divorced in 1974. He and their children relocated to Hawaii, while she remained in Glencoe, Illinois.

After twenty years as a children’s writer and illustrator, Kane experienced “a midlife crisis of sorts. I dropped all interest in my art and turned my attention to spiritual exploration and growth. This consumed me for several decades and still is a vital part of my life. However, a number of people shamed me for neglecting my art talent and I decided I should get back to it.” She began to pursue fine art painting. Her first watercolor, “The Children’s Tree”, won a prize in a local art show, and she followed it with paintings that were displayed in local libraries.

Kane moved to Plano, Texas in the early 2000s to take advantage of the warm climate and the proximity to members of her extended family, including her cousin Cynthia Porter. “Sharon was a very private person and rarely came to my house or my son's house,” Porter recalls. “We all enjoyed listening to her stories, especially about her childhood, and we would get out one of the Jennifer books and she would read a special passage from it. My mother, her mother's sister, also lived in Plano, and with much coaxing, I could get them together to enjoy the stories. Sharon's mother and she were very reclusive. I know Sharon loved her yoga, water aerobics, playing mahjong and getting together with a group of ladies at the senior center in Plano.”

In 2014, Christy Ottaviano Books, an imprint of Henry Holt and Company, published Kane’s final book, Kitty & Me, based on her and her daughter’s “avid love of cats, the beauty of [the] feline form, and the joy of cat companionship.”

In 2014, Christy Ottaviano Books, an imprint of Henry Holt and Company, published Kane’s final book, Kitty & Me, based on her and her daughter’s “avid love of cats, the beauty of [the] feline form, and the joy of cat companionship.”

In 2018, Kane donated an archive of nearly 300 original Buttons an’ Beaux cartoons, clippings, and a scrapbook detailing that era of her career to the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco. This work served as the foundation of the Cartoon Art Museum’s 2019 exhibition The Teen Age: Youth Culture in Comics, and the first public display of Kane’s cartoons. When notified of the exhibition, Kane replied, “It is gratifying to me to know that Buttons an’ Beaux will have renewed life through you, and that new generations of teens will be able to enjoy my work. Clothing fashions may have changed—we never wore jeans to school! It was the sweater and skirt era!—and I’m sure our vocabulary was much milder, but the teenage angst is still the same.”

Kane was courteous and kind to the end, taking time to correspond with friends and well-wishers while carefully packaging up paintings, photographs, and signed copies of her children’s books for dispersal among her family. “In Plano she led a quiet life, but it was much to her liking,” notes Cynthia Porter. “She was very much into astrology and would welcome the alignment of the planets at times as she wanted to die when that happened!

“She was a thinker, an author, and a supreme artist. She often said that Little Mommy was the pinnacle of her pride and joy. She is resting now in the place she longed to be as her health was failing. I know she is at last at peace.”