This is the second unauthorized Batman comic to be written by Josh Simmons, that unsparing specialist in physical, emotional and moral breakdown. The first one was a self-published minicomic printed in 2007 under the simple title of Batman and subsequently posted online; it depicted the caped crusader at his most ideologically severe, lecturing a disgusted Catwoman on how he's devised a magnificent means of permanently disfiguring criminals. Batman cannot ever kill, you see, so it's crucial that the superstitious and cowardly lot that is the criminal element be marked - to live forever with the shame of their transgressions, and to be shunned, then, by all the good people of society. On its own, this is not an original idea. Lee Falk's transitional superhero character and Batman predecessor the Phantom left the mark of a skull on the jaws of those villains he struck, while the yet-earlier pulp character the Spider stamped his brand upon the foes he felled, but Simmons' Batman is depicted with unusual intimacy: knees pressing against his chin as he curls up to dream of packed prisons and children getting blasted with fire-hoses, swooning ecstatically, high above a tottering riot of Gotham rooftops.

People make fan fiction for a lot of reasons. Sometimes, it is a form of participation with the stories you are following - a means of declaring your allegiance to favorite characters, stating your desire for a ideal outcome. But often it can adopt the stance of opposition. It could be that the work did not directly address your place in the world -- your gender, your race, your society -- though it spoke to you powerfully nonetheless, and in those cases the characters become alphabetical: a means of building ideas about yourself in a shorthand readily known to those who've joined you in appreciation of the work. You can be critical, if you want, and very self-referential. Indeed, if you do this in the United States, you are more likely to enjoy the protections of fair use; Simmons' Batman needed only a few dialogue alterations and a title change to "Mark of the Bat" for inclusion in his 2012 short story collection The Furry Trap - there is a massive body of Batman parody out there as precedent, after all. My favorite has always been the 1990 Pat Mills/Kevin O'Neill one-shot Marshal Law: Kingdom of the Blind, which portrays Batman as an avatar of police power, striking terror into the populace as a means of encouraging responsive violence, and then using that violence to justify the necessity and expansion of his own activities. It is scathing, and very prescient, but also a raucous lampoon crammed with bad-taste jokes and dubious plotting, headlined by a charismatic original anti-hero character who can be plugged into different situations. Simmons, in contrast, focuses totally on Batman (or "the Bat"), devoting a great deal of space to studying the character's physicality: how he climbs up walls; how he swings through the air on his cord; how his body smacks painfully against buildings. This Batman is parody, yes - it's transformative, but also intimate in a way that places Simmons deeper into the territory of personal fan fiction than earlier japes.

Twilight of the Bat retains the allusive character of "Mark of the Bat" — the "Bat" is now joined by the "Joke Man," former foes left wandering together through a post-cataclysm G-- City, a no man's land so ruined by (unspecified) disasters that it seems these characters may be the last two beings alive in the world. In this way, it becomes both a commentary on Batman and a sort of travesty on Simmons's own 2015 graphic novel Black River, which followed a group of survivors through a post-apocalyptic terrain as they transition from notionally hopeful and empathetic people to a starved and amoral state, the snowy landscape through which they trudge fading into annihilative blank white. That book, in turn, was a more genrefied structural parallel to Simmons's 2007 book House, a wordless and very formalistic depiction of characters becoming trapped in utter, inescapable hopelessness, its panels gradually becoming smaller and its pages darker and darker, until at the end they are pure black. I did not like Black River as much, because Simmons's introduction of semi-detailed characterizations and familiar scenarios of capture, exploitation and retaliation hew close enough to stock devices that the scheme feels half-formed and oddly aloof, less a personal impression of survivalist or "zombie" fiction (or a novel rendition of the type) than an abbreviated summary of a more nakedly commercial enterprise.

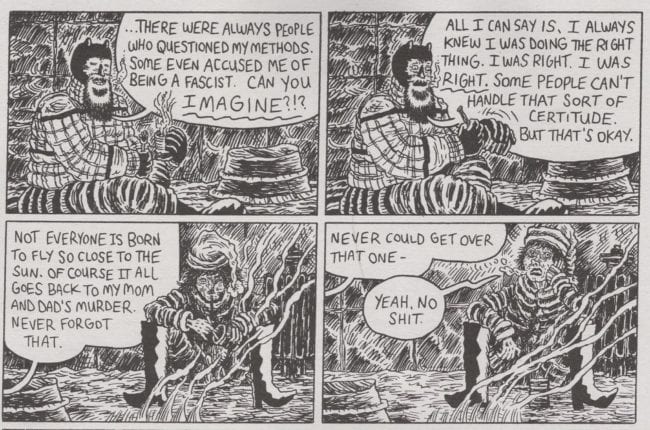

This comic benefits from a tighter and more focused reprisal of the same theme, made acutely reflective by the fact that it is drawn by a different person: Patrick Keck, whose solo work mines a vein of grotesque fable and spaghetti-and-meatballs psychedelia. His drawing here, though, reads like an ill mutation of Simmons's own "Mark of the Bat" approach; the tilted angles and pooled blacks of Simmons's G-- City now seem rotted and mossy with hatches and scribbles, the formerly clean character art wobbly and wrinkled from age and trial. Batman sports a beard and mustache along with his cowl, which makes him look like an awkward animal, while the Joker's bugging eyes and stringy hair suggests an aged and manic pop star, which is fitting, as Simmons-the-writer is using him as a trickster figure: a caster of glamours, explicitly manipulating Batman's desires in the way the devices of apocalypse fiction implicitly did to the Black River crew. Gaslighting at the end of time.

If you've read the "classic" Batman comics, a lot of what Simmons & Keck do here will be familiar. At one point, Bats and the Joke Man collapse into uncontrolled mutual laughter, as in the famous denouement to Alan Moore & Brian Bolland's Batman: The Killing Joke. Much of the Joker's flirtatious characterization seems inspired by the homophobic nightmare concocted by Frank Miller in The Dark Knight Returns, and Simmons does nothing to ameliorate the disgust in which that work trafficked: here, the Joker vacillates between ass-shaking come-on and vulnerable declarations of love for his foe, while Batman feels the need to handcuff him to a pole at the end of each day "so you can't do anything weird to me at night." In the morning, mysterious cupcakes are left for the pair, filling Batman with a sense of hope for humanity's future, though Simmons portrays this as part and parcel with his rigid and cruel morality, which the Joke Man taunts in between sympathetic flights of conversation. Yet as the story creeps onward, one gets the impression that the villain's emotional shifts are not quite organic; he seems to be playing roles, explicitly and metafictionally alluding to well-known prior characterizations of "the Joker" as part of a very simple plan, one evident more to the savvy reader than Simmons's blinkered Bat.

I don't think any of this is meant to be subversive; or, at least I hope not, because that would be a waste of effort. The contours of this story recall a comic the artist Richard Corben once did with the veteran mainstream writer Garth Ennis: 2004's The Punisher: The End, a hypothetical "final" story for the death's head-bedecked Marvel vigilante, finding him in a post-nuclear wasteland and suggesting that, if given ample opportunity, the character's nightmare righteousness would result in the extinction of humankind itself. Such critical sentiments have not stalled the character's adoption as a mascot of rapidly-militarized police departments here in our real world, where it remains a profitable holding in the Disney entertainment empire. Watchmen didn't end superhero comics - it only ensured that superhero publishers would make more Watchmen. Maybe it's for the best, then, that Twilight of the Bat uses the characters as language, to spell out a very Josh Simmons story of despair. The Joker is storytelling in flux: the idea that genre expectations or beloved characterizations exist mainly to prompt reactions in the consumer. Batman is the consumer who cannot see this greater structure - he takes everything completely on-the-nose, as flatly as a moralism that dictates you punch crime until it stops. The sum of this equation is the same as Black River, as House. You're left holding nothing at all.