The standard progression of horror stories, in which events become worse and worse, is often described as "a descent into hell." Such a descent is the literal plot of Fabien Vehlmann and Kerascoët's Satania. Kerascoët, a pseudonym for a married couple working collaboratively, have a style that betrays no surface ugliness, and so does not hint at the horror to come. They recently illustrated a children's book written by Malala. Their work is friendly and welcoming, bright with color. Through the lens they provide, it is easy enough to interpret what is happening as a fantasy narrative, a story of exploration, in which dangers might bring harm to peripheral characters, but will not make too caustic an impression upon the psyche of the reader.

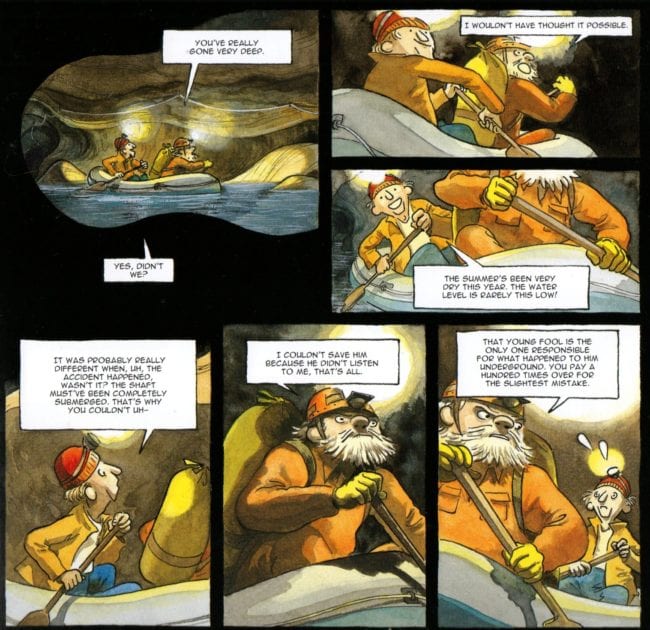

Readers of Vehlmann and Kerascoët's previous collaboration Beautiful Darkness might be more prepared. There were a number of them; that book was a hit. Kerascoët's work is, as the book's title stated, beautiful. It functions typically, with cartooned characters moving inside of more realistic backgrounds. However, the linework on the figures remains lively, sketched out and improvisational, in a way found more often in the energy of storyboards than the labored-over end result most cartoonists working in an animation-derived style employ. The watercolors they employ then adds to the texture that defines the backgrounds' detail and keeps up with the spontaneity of the characters' acting. The cumulative effect grants a sense of depth to these worlds, and the darker aspects of Vehlmann's scripting do not subvert Kerascoët's skill set so much as excavate it. Beyond the foregrounded elements, another form of life is breathing, and there is a deeper meaning in play beyond the surface pleasures.

Still, it is useful to read the story using the frame of fantasy. We can interpret the idea of hell, or religion in general, as fantasy, a hope for a world of moral surety prosaic living lacks. The plot has a young girl looking for her older brother in the caves beneath a mountain. The brother has theorized that demons, as an image that reoccurs throughout various cultures' mythologies, are a race that evolved from neanderthals, choosing to live underground. This theory is never exactly refuted, although the notion that follows from this idea, that such "demons" might actually be benevolent or understandable, is. This aspect of the plot suggests that "rationality" is just as much a fantasy as religion is. The reality of life is ruled by insanity. This is made clear by the fact that the mother of our two explorers is in an insane asylum, after claiming to have been raped by demons. A la Werner Herzog, the "natural world" of Satania, this hell-not-hell, is a brutal place. Any denial of this is a coping mechanism the characters use to justify their moving forward, which only brings them deeper into hell.

This also means being brought in touch with the uglier parts of their nature as they go about their quest. These characters are not necessarily bad people, but they are essentially where bad people go where they die, and the question of whether their fate should be considered sealed, with them already dead, is certainly up for debate. If we as readers believe that the characters are not dead, are indeed still on a rescue mission, we might be denying the reality of death as surely as the religious do. The language of religion, mentions of God and eternity, is invoked casually, functioning in the dialogue as both a way of adding realism even as such words seem loaded with thematic heft. The structure effectively disguises the stakes of the story, casting into doubt how doomed the characters are, how decent they are, the extent to which their decency will save them, and how much it can be corrupted.

Charlie, the book's heroine, never betrays her fellow travelers over the course of the story. The sinful aspect of herself that she instead embraces is a burgeoning sexuality. Readers who find such facets of humanity morally neutral might still be disturbed in their manifesting in a character both drawing style and genre conventions code as being rather young. This effect is certainly intentional, and it's a book translated from the French; what are you gonna do?

There will also be those who are bothered to discover the book has typos galore. Weird ones too. Words in lines of dialogue are repeated, and there are moments where it seems like the computer font choices are glitching in some way. Why else would the letter combination "fi" be deleted from the beginning of two different words on the same page?

If you were to hear the title, and learn that the lone human figure on the cover is a young woman with bare breasts, you might reasonably think, "Oh, I didn't know Danzig was still publishing comics." But it becomes immediately clear when you see the book that it is something else. When you read it, you're reading a great comic, visceral in its storytelling, sophisticated in intention. Throughout, the emotional reality is as immediately understood as the readability of the images themselves. While the world in the background of Beautiful Darkness consisted of photorealistic painting, the hellscape on display here is necessarily more abstracted. The desires that drive Charlie, before she gets into demon-fucking, are to be reconnected with someone who has disappeared. After that, she's only trying to make a home in a chaotic universe.