"This is not the kind of memoir where you want to see your name come up." So said my editor about this rare bookshelf original from Adrian Tomine, one of the American literary cartooning figures who needs no introduction, and therefore can support so high-profile a collection of scenes from his life. But while The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist adopts the character of autobiography, it is predominantly a comedy of middle-class neurosis, set in the world of 'acclaimed' but culturally marginal art, with all of the microaggressions and voluptuous self-loathing you would expect from a defensive and oft-fatalistic scene. As the book begins, Tomine is a small child at a new school who cannot stop talking obsessively about comics, and cannot help but become aggressive when his classmates laugh; within the space of four pages, he is so bullied and ostracized that his teacher has to force unlucky kids to sit next to him at lunch. CUT TO: the 1995 San Diego Comic-Con, where a grown Tomine, basking in the glow of the acclaim that followed his early work in minicomics, receives a rude awakening in the form of The Comics Journal #179, in which Jordan Raphael graced the magazine's "Shit List" column with a bellicose takedown of the first Drawn & Quarterly issue of Optic Nerve, written with that special blend of enormous self-confidence and just enough imprecision to assure readers that the critic has not wasted too much of his valuable time on obvious trash. CUT TO: a Comic-Con afterparty, where Tomine seeks the fraternity of fellow artists, but instead finds himself roasted by peers for the similarities of his work to that of Daniel Clowes. The evening ends with our man upbraided at length by a fellow attendee for self-interested careerism in failing to place Optic Nerve with a smaller publisher.

But an author is never defenseless in their own book. Look at this dipshit's haircut: absolute character assassination.

Published by the aforementioned Drawn & Quarterly, Loneliness comes in the form of a facsimile sketchbook, which is conceptually a bit unsettling - did I steal this from Adrian Tomine's house? I think it's supposed to be more like Tomine is beckoning you closer for special access to his unmediated innermost feelings, although the drawing of it isn't actually a great departure from what has come before. Scenes from an Impending Marriage (2011) was Tomine's last 'sketchbook'-styled comic, but one can draw some comparison between that and the stories collected in Killing and Dying (2015), which, though more formal, saw Tomine gradually backing away from the cinematographic shadow-and-light effects and varied 'camera' blocking of Shortcomings (2007) and toward a pared-down method of depiction: dot-eyed characters set against suggestive backgrounds, most often in medium shot and medium close-up. Here, as in Scenes, Tomine largely swaps solid blacks for hatching, but it still appears of a piece with his current interests in cartooning.

In this way, the most informative comparison point might be Truth Zone - Simon Hanselmann's line of disguised nonfiction barbs re: alternative comics and the industry surrounding it; those pages too are pared down a little from Hanselmann's flagship works, but they are not immediately identifiable as a side-project by the terms of their composition. Yet there is a crucial difference between these artists: there is a prideful hardness to the worldview of Truth Zone, by which Hanselmann reminds you that he is, ultimately, a little cooler than the clowns he is teasing. Tomine's book cannot bear to suggest such a thing; its author sweats and seethes through a long series of small vignettes, six panels per page, capturing awkward incidents from over the course of more than 20 years. At the same time, longtime readers will nonetheless be reminded of Optic Nerve; among the feelings evoked by those issues, particularly from those collected in Summer Blonde (2002) onward, the most distinctive -- perhaps the very thing that firmly sets Tomine apart from a Dan Clowes or a Jaime Hernandez as a storyteller -- is what is popularly known as "cringe." The '01 Summer Blonde story "Bomb Scare", with its dense layers of humiliation and back-biting among high school losers, may be the quintessential study of cringe in the Tomine catalog, arriving just as film and television began to turn away from acid sociology a la Todd Solondz to develop the subject matter into a very lucrative mainstream comedy form. Thus, the '15 title story of Tomine's Killing and Dying, concerning a father's fraught attempts to support his catastrophically untalented daughter's career in stand-up, felt like a sort of valedictory.

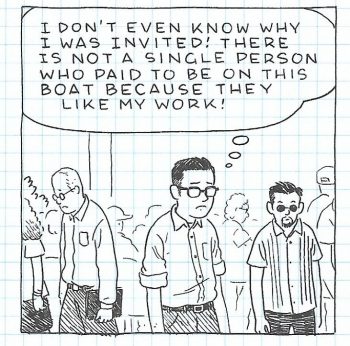

Now, Tomine himself is the focus of comedy - and he's not averse to playing it broad. Put him on a nice walk with a pretty girl, and the poor guy's overcome with diarrhea. A stressful situation in Penn Station ends with him making a nonsensical threat of bodily harm to a little old lady; the whole room falls silent. Searching Carnegie Hall for the studio where he's scheduled for a big interview... dear reader, he walks right into the dang ladies' dressing room. Some of these sketches are very good, like an immaculately-paced bit where he's doing a career day presentation at his daughter's school, ramping up childish gross-out jokes to the abrupt chagrin of adult administrators. Some of it's also quite trenchant: while ostensibly welcoming to every misfit, the '90s/millennial alternative comics scene was enormously white, and there is a running account of thoughtlessly racist moments throughout Tomine's book, from every conceivable mispronunciation of his name, to an oafish retailer seating him for a signing underneath a poster for Frank Miller's Sin City storyline "That Yellow Bastard", to a distinguished older cartoonist asking Tomine his ethnicity, and then declaring "I love jujitsu." That last one takes place in 2010. And then there's an amazing two-page sequence set during a comic book-themed cruise to Mexico, basically a comics convention on a boat - immediately, a hierarchy of talent is established by the desires of the paying attendees, and the event becomes a synecdoche of the comics industry itself, where mass appeal and big sales are the only criterion for success: you're either Neil Gaiman, or you're watching people crane their necks away from you and toward Neil Gaiman.

However, good as the jokes may be, Loneliness aspires to be something else. After about 120 pages' worth of brief exploits, Tomine begins to feel a pain in his chest, and the remainder of the book plays out at almost exactly the length of a new issue of Optic Nerve, as a single continuous storyline on the artist's fear of imminent death. It's far more dramatic in texture, and even the visual style becomes slightly more varied - a splash page, at one point, is devoted to Tomine nervously pouring out a goodbye letter to his wife and daughters. I don't think it's a spoiler to note that Adrian Tomine is still alive, so the purpose of this sequence is to provoke some climactic reflection on life. "But still... my clearest memories related to comics -- about being a cartoonist -- are the embarrassing gaffes, the small humiliations, the perceived insults..." The artist rubs his chin. "Almost everything else is either hazy or forgotten." And thus, we understand that the structure of the book is not just 'the book', but Tomine physically recounting to himself, via drawing, all that he recalls of his cartooning life, for the benefit of understanding himself, and that is why the book is published in the form of a sketchbook, and: clever! It's clever.

It's also very sentimental - and, in a way, conservative. At the core of this book, is a great longing for an elusive normality. And what is normal, in this book? Mostly uncontroversial things: to be relaxed and enjoyable in social situations; to have close, supportive friends; to be respected for your hard work. Tomine is acutely aware that he has done very well, living with a wife and children in a good Brooklyn neighborhood where he works on prominent illustration assignments and exactly the comics he wants - he expresses angst about such fortune to himself, as we would expect from a sensitive character. But in the structure of his vignettes, Tomine is firmly protective of the way things are. This is a book about personal experience, articulated entirely in interpersonal terms - so, for example, when money is discussed in this book, it's in the form of D&Q founder Chris Oliveros circa 1996 going off on a wistful account of his publications' lack of popular appeal, capped with a panel of Tomine gazing blankly at his seat for a signing. It's a funny bit; awkward. Everything in this book, in fact, is inevitably distilled to personal feelings of anxiety, inferiority, awkwardness, etc., so that all of the comical situations facing Tomine are affronts to the normalcy idea. Systemic objections are always placed in the mouths of villains. A man who objects to the implicit hierarchy of receiving autographs from celebrity cartoonists, is also a deranged stalker who is eight panels away from screaming racial insults. A reader who questions the idea of 'innovation' in comics that operate under the values of novelistic prose, is voicing those concerns as an arrogant gotcha at the end of an author Q&A - he's a prick. In what must be the cringe apex of Loneliness, Tomine is on a date with a woman, and they find themselves seated next to a couple who are discussing Summer Blonde; not only does one of the adjoining pair not like the book, he browbeats his companion toward admitting that Adrian Tomine actually kind of fucking sucks - and, in his derision of gen-x psuedo-profundity and the emptiness of ambiguous endings, the hater's narrative recalls Jordan Raphael's takedown of Optic Nerve from the beginning of the book. Tomine's date stands up to defend him, but he is too polite not to beg her to stop! This woman will become his wife, and support of Optic Nerve is verily a metaphorical support of family, empathy, and happiness.

And then you realize: before the snarking peers, before the nasty critics - the first objections to Tomine voiced in this book are those of mean little schoolroom bullies.

Ah, but can’t an artist be proud? Can an author not use his own book to have a laugh or two? The thing is, by its own terms, this book is not mere comedy: conceptually and thematically, it's a means to evaluate the longings of life. And on those terms, the book skips gaily along the surface of a self-deprecation that is really an appeal to sympathy. But I like Tomine's comics. And when you've read a lot of his comics, you realize that this artist finds the heart of engagement in the absence of resolution: all those ambiguous endings. Loneliness is ambiguous too, in that Tomine declines to answer the question he raises of whether this project represents any realization about himself. Maybe it all means absolutely nothing. One again shrugs enthusiastically - surely this book is the only type of it that Adrian Tomine could make.