Stephen Collins's fable about a tidy society menaced by the otherness of a man's beard that mysteriously would not stop growing, The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil, is notable for the extreme dryness of its wit, the detailed but lively nature of the drawing, and the nihilism at its center. It follows an unfortunate turn of events for Dave, a typical worker on the island of Here, a land known for its fastidious attention to order, detail, cleanliness, and predictability. To do otherwise would be to invite the unknown, specifically the unknown chaos of There, the dark and frightening land beyond the sea. One day, Dave woke up with a beard that will not stop growing. All efforts to curb it, first by himself and then by exploitative researchers and the government, fail. Here's stylists are conscripted to shape the beard in a series of scaffolds, another initiative that fails--hair does what it wants to do, after all. Finally, with their society starting to break down a little, they attach the beard (and Dave) to a series of balloons that float away over the sea. Everyone learns to accept a little bit of chaos in their lives.

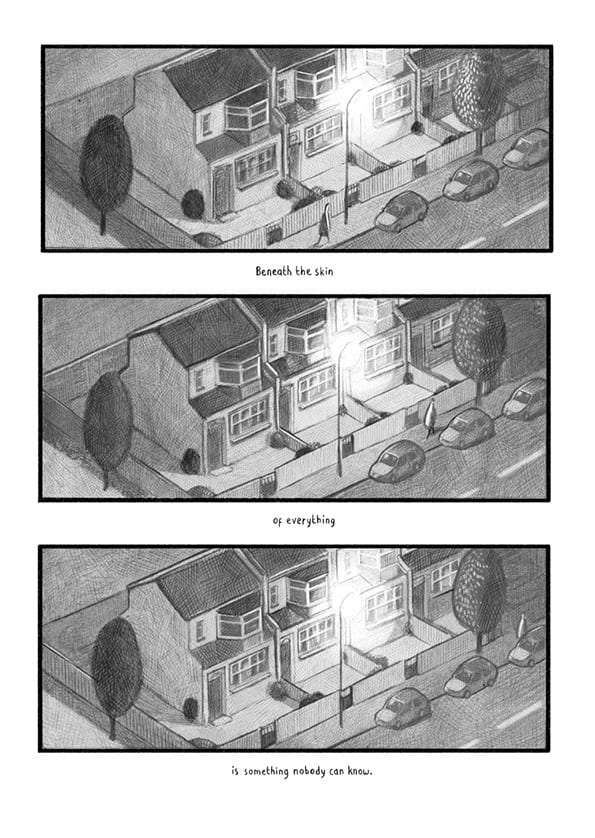

Except that that's not quite the end. This is a book that ultimately is about looking. Dave's one hobby, the one thing that staves off the existential dread that is There, is drawing. This is where Collins's skill with a pencil is so important, because in addition to his precise and charming pencil drawings that make up the book, he also draws Dave's own pencil drawings, which are equally charming and precise in their own way. Collins points out that what one chooses to see and highlight is largely a matter of perspective and choice. Before he was beset by his beard, Dave chose to draw things (houses, cars, streets). After the beard took over his life, the one thing he is left with is drawing, and once he starts to draw people, he soon begins to notice their irritating differences. Having the beard, and the beard phenomenon in general, forever alters the way everyone looked at the world.

Collins gives the readers many different ways to look at the story. There are huge splash pages, multi-panel grids that break down into fine detail, single images split among many panels, close-ups, assorted eye pops and background jokes, and many other approaches at breaking up the page and keeping the reader off-balance. There's no rhythm to the story or its visual approach, even in the first chapter when Dave's life is still entirely normal. That's because the fear of There (made manifest in dreams when black, hair-like tendrils grasp the unwary) is always there to disrupt order on a subconscious level. It's a sort of repressed mass hysteria that affects their overall grasp on reality. For example, Dave's job was producing statistics and charts for his company. The only problem was that no one remembered exactly what the company did anymore, only that they all produced nice and neat paperwork.

Collins gives the readers many different ways to look at the story. There are huge splash pages, multi-panel grids that break down into fine detail, single images split among many panels, close-ups, assorted eye pops and background jokes, and many other approaches at breaking up the page and keeping the reader off-balance. There's no rhythm to the story or its visual approach, even in the first chapter when Dave's life is still entirely normal. That's because the fear of There (made manifest in dreams when black, hair-like tendrils grasp the unwary) is always there to disrupt order on a subconscious level. It's a sort of repressed mass hysteria that affects their overall grasp on reality. For example, Dave's job was producing statistics and charts for his company. The only problem was that no one remembered exactly what the company did anymore, only that they all produced nice and neat paperwork.

One of the other major characters in the book is a philosophy professor named Darren Black, a leading theorist about There who's brought in to see Dave and his problem. Of course, he exploits Dave by tricking him into signing a release that allows him to be filmed at all times. Black is genuinely distraught when the government essentially exiles Dave, but it doesn't stop him from getting into the Dave business once he's gone--creating a museum in his old house and writing several bestselling self-help books about the "Beard Event." As noted earlier, the easy moral of the story is that if we stop fearing chaos and let a little of it into our lives, our lives will be more interesting and we will be happier as a result.

Except that's not the ultimate moral of this tale. Long after Dave was sent away, Black and his workers find little scraps from Dave's sketchbook, the one that he took with him as he floated away. The drawings in the early pages are of the balloons, Here from a distance, etc. Later on, the drawings are simply of blackness. Collins suggests that the void of There is quite real, all-encompassing and certainly to be feared. It's the argument of an existentialist suggesting there is nothing awaiting us beyond our lives as we live them. There is no higher order to make sense of it all. There is only random chaos that we try to make sense of as best we can. Indeed, the trick is to understand that the void awaits us all while still trying to create one's own sense of meaning in the time we have allotted to us. It's a fate that forces us to live life and make choices and not just sit back and passively observe, and it fittingly puts the lie to all that the slightly oily Black believed in. It's a challenging ending to a book that packs a lot of doubt and terror into a dryly witty and even whimsical package.