The year of COVID quarantine rendered living in cities next to meaningless. All those square miles of buildings pressed up against each other had their interiors off-limits, and any conversations with acquaintances on the sidewalk were kept curt, as human interaction was distinctly frowned upon, if not fraught with terror. Part of the premise of society is that well-meaning strangers can be entreated to help one another if necessary; in lockdown, it no longer felt like that existed, as atomized individuals were told to limit themselves to pods consisting primarily of those with whom they shared a residence. The days of seeing a person you knew on the street, and joining them on their journey if you didn’t have anything more pressing to attend to, seemed over. Even in the United States, a nation that loves individualism and competition, single-family dwellings and personal automobiles, and where the mood of many regions is still defined by the coldness of puritan ancestry, it was a lot to adjust to. When people air opinions like “Can you believe we ever blew out birthday candles? Gross!” a European cosmopolitanism of greeting people with kisses on the cheek can seem like a fantasy of pre-Enlightenment naïveté.

After a year-long delay, Brecht Evens’ The City Of Belgium arrived in early June 2021 with little fanfare, as if its cavalcade of partiers, reveling in social life in full flower, might still be considered gauche. It’s Evens’ most ambitious book yet, following three leads as they move through different locations and interact with various people over the course of a night, but Evens is such an accomplished visual artist that his subject matter is invariably imbued with a degree of significance that may in the moment feel like too much. An illuminated manuscript style, suitable for a tale of angels and demons, is found chronicling a restaurant at its dinner hour. I don’t think there will be a better-looking comic released this year, but it reads as if Go or 200 Cigarettes had Sacha Vierny as a cinematographer. Whether readers will be in the mood for something so sumptuous in its depiction of city life -- intended to capture romantic possibilities that for now feel lost to nostalgia -- is an open question, but the book reinforces that Evens is comics’ foremost impressionist of overstimuli.

The basic readability Evens achieves still feels like an innovation in painted comics. His ability to direct your attention towards small moments while depicting everything with a superabundant lushness is beyond impressive, literally; it is an effect that works only because the reader is not constantly taking note of it. The reading experience is defined by becoming accustomed to a very high level of visual splendor, then still getting hit with a page that feels like an absolute showstopper. When the scratchboard gets broken out, or we hit a two-page spread moving through the floors of a nightclub that switches perspectives from bird’s-eye-view to eye-level somewhere around the spread’s center, readers are reminded Evens can do things no one else can. The look on the face of a dancer, humbled by enthusiastic applause, feels startlingly precise when first encountered - and when we later spend dozens of pages in her company, our attention seems rewarded; though we shouldn’t congratulate ourselves, as it was being consciously directed in the first place.

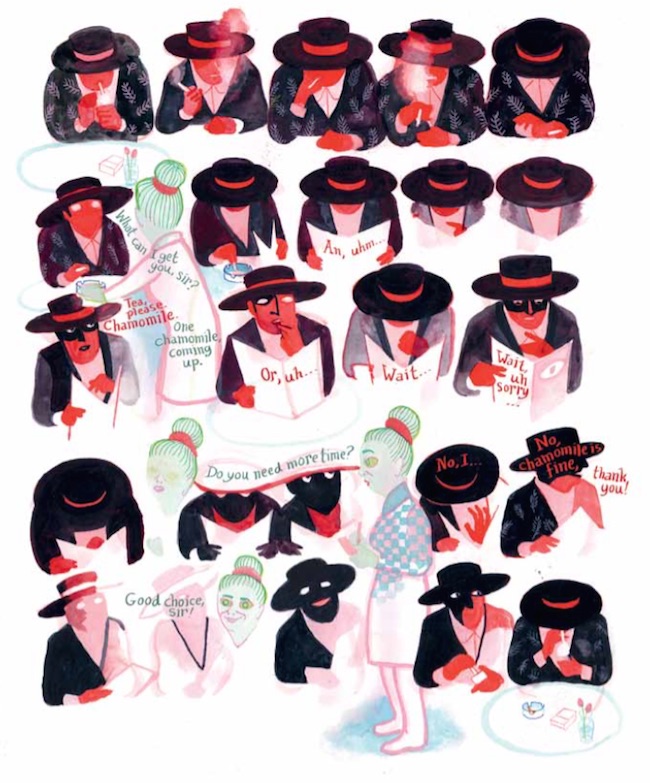

Evens color-codes his watercolor-painted characters, their words floating unbubbled in ink that matches their overall design. This is the great innovation that’s characterized all of his books released in English by Drawn and Quarterly. (An earlier wordless comic, released by Top Shelf as Night Animals, shows painted color bound by a black ink line.) In this book, as our main protagonists, we’ve got Jona, who’s blue, Rodolphe, a red guy, and Victoria, a green woman whose hair is laden with multi-colored beads. Stipulating who the book’s main characters are, however, might constitute a spoiler of sorts, as this is one of those sprawling cast kind of deals - when we’re introduced to the latter two, having conversations with others, it’s unknown who we’ll end up following once these extended scenes conclude. Another character that features prominently is a taxi cab driver, who ferries all three leads around the city; Rodolphe ends up at the Disco Harem nightclub, previously seen in Evens’ 2010 book The Wrong Place. The Disco Harem seen in The City Of Belgium might show some of the same architectural features as in that earlier book, but it’s presented in a far more atmospheric and dynamic light. A reread reveals The Wrong Place to be a good deal muddier and less assured in its drafting than Evens’ follow-up works, but it still explored the parameters of what his style could ably do, with a multi-page sex scene seeming like an intuitive culmination of what his approach suggests. If sex remains the subtext underlying all human interaction, this is doubly so in Brecht Evens’ comics, where clothes and skin combine to make the body a transparent entity primed for transformation.

The first character we meet in The City Of Belgium is aiming to change his life. Jona plans to move to Berlin the next day to be with his beloved, but it’s clear from the title of the book we will not get to see him there. Over the course of the night chronicled, we learn his backstory and get an idea of what he’s fleeing from. Despite a character design that scans as “hipster douche,” Jona's past includes a prison stint and old friends with violent tendencies. The night is long, and pages may pass where it feels like nothing is happening, but character is revealed in an offhand way over the course of reading. In a 2016 interview, Evens mentioned being a fan of John Cassavetes and expected this book to be inspired by his films. This primarily manifests in terms of pacing built around long extended scenes of conversation, but after we meet Victoria, it becomes clear that, like Gena Rowlands in A Woman Under the Influence, she is struggling with mental health issues verging on a breakdown and is being treated with a degree of self-conscious paternalism by her loved ones.

The multidimensional technicolor visual approach Evens employs is a far cry from the black-and-white-for-economic-reasons look of a doggedly independent film like Faces. Still, the translucence of watercolor brings a degree of transparency to Evens's compositions that leaves little room for error, and makes the creation of a painted page into an exercise in improvisation. Whether these compositions are worked out in advance in pencil I don’t know. The unbordered panels and unconventional page layouts would probably render such things looking like Connor Willumsen pages. The few instances of black ink line drawings we see in The City of Belgium make me wonder how a fully black and white short story from Evens would read. The flatness of how it’s used looks great in contrast to the varying gradients of the color work, providing a moment to rest one’s eyes.

The conclusion of the book has those gradients fading away to white in the bright light of morning, as if bringing the reader out from the vivid dream the book presents into the world of waking reality as gently as possible. Rodolphe stands on a beach, transformed and reborn through a series of fortuitous encounters into something other than the depressive sad sack he was at the story’s outset. But circumstances prevent this book from being as transformative a work of art as the character arc depicted. It arrives on our shores at an awkward moment, where readers no longer need to live vicariously through fiction the way they did a few months ago, but life is not yet in full swing enough that depictions of active socializing show us how we live. So, it is simply an addition to Brecht Evens’ impressive body of work. If the landscape of comics hasn’t been reshaped by its presence, it can still be a landmark, placed in the public square as something to admire.