Canadian cartoonist Fiona Smyth's new collection Somnambulance chronicles thirty years of comics, from her early work at the Ontario College of Art in 1995 through a 2015 zine. Normally, you'd expect such an expansive collection to feel disjointed, or at least heterogeneous. And sure enough, there is some variation; Smyth's first comics are relatively cramped; over time she started to play with color. But even with such shifts, Smyth's art is remarkably coherent over time, mainly because she's so dedicated to incoherence. From Somnambulance's earliest pages to its last, Smyth resolutely works to bend, fracture, and flat out ignore the "sequential" part of sequential images. Each overstuffed, vibrating, oversexed panel seems to freeze and burrow into the page or into your skull, distracting you from the next image, which, in turn, distracts you from the next, and the next. These are comics in which the panels don't so much work together as lovingly fight for dominance.

The eschewal of plot in the comics is tied into Smyth's feminist project. In her famous essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, critic Laura Mulvey argues that traditional Hollywood narratives, and the conventions of plot in general, were structured around a male viewer and male pleasure. Men, she argues, are supposed to identify with a male protagonist as he overcomes trials, defeats foes, and wins women. Narrative provides a kind of male empowerment. Men get to become more manly as they follow that hard, upright path from beginning to end.

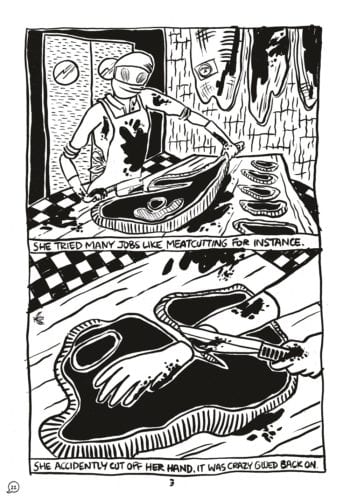

Smyth does occasionally gesture at progression. In one series of strips a girl from the city goes to a small town to dry out, and then tries to sleep with a hot guy. In another a stoner type guy goes on an indeterminate quest involving the back tattoo of a dead man and the lost breast of Clitomenstra. These storylines wander around for a bit and then peter out. The promised sex never quite happens, the mystical revelation dissipates. Instead of providing conventional closure, Smyth half wraps both storylines up by bringing all the characters together in an art gallery years later to chat about the work on the wall and reminisce about old times and all the things that didn't quite happen way back when.

Even this much resolution is unusual, though. Mostly the comics follow a dream logic or no logic at all, as twisted sexualized figures float and morph across vaguely biological landscapes, with interior and exterior inverting or sliding into one another. On one page, a snake with the head of a woman twines itself around the extended neck of a cow-thing with the same woman's head, and the two climb a mountain accompanied by a cat and a bird creature. In the last panel on the page they float through a cosmic labia, rendered in inky pen slashes that make the image seem to vibrate. The comic is giving birth to itself, or returning to the womb, or both. Creation mirrors and swallows creation.

In her essay, Mulvey says that narrative cinema is often frozen by images of women. She notes how "conventional close ups of legs…or a face…" freeze the narrative, giving it a "flatness, the quality of a cut-out or icon." This is exactly what happens in Smyth's images, in which breasts, and sexual organs float free of context, and sometimes of bodies, forming cryptic messy erotic tableau that point nowhere. A giant head with hands for eyes and a vagina in its forehead rolls out a preposterously extended tongue. That tongue touches another severed heads smaller tongue, while a topless bunny woman declares, "the head is ruled by other than the heart." The giant head responds, "Stinks."

But in getting rid of the narrative, Smyth implicitly gets rid of a unitary viewer as well. Her images are cluttered with lines, and often text is integrated into the background; it's rarely clear where your gaze is supposed to go or end. Rather than the gaze taking control of the female body, the body swallows up the gaze, or the gaze turns into the body. Smyth's disturbing disembodied eyes are shaped a good bit like her disturbing disembodied vaginas. In one 1997 zine, a panel shows a fertility goddess with hearts in her eyes leaning over as droplets fall from her breasts; the next panel shows that one of those droplets is an eye. Rather than presenting the body for the look, Smyth shows the body giving birth to vision. Her comics are one version of what a body might see if it had eyes.

In part perhaps because Smyth is seeing from the body, and in part because she mostly avoids narrative, the comics in Somnambulance are, often, paradoxically, comforting. The sexual and sometimes violent imagery is in line with the underground's history of deliberate shock; Smyth and Johnny Ryan are clearly working in the same broad tradition. But instead of trying to disgust, as Ryan does, the abstractly embodied sex and fluids and vibrations in Smyth's work feel cheerful and enthusiastic—celebratory rather than repulsive.

Even a story by Patty Powers about a brief sexual encounter with a dog is transformed in Smyth's images into a kind of ecstatic vision. Powers' text concludes by talking about frustration of both dog and woman, "We were both horny and confused. And we were probably thinking the same thing "wrong species."

Smyth takes that wry joke, and gallops away from it, drawing a multi breasted cat woman romping with a dog man against a flowery erotic comforter. It's an additional extra-narrative vision, breaking from the embarrassment of autobio, and launching out into a prelapsarian space where bodies exist in each moment, freed from the judgment of sequence, and the moral at the end.