The third and final volume of Ryan Standfest's black humor anthology Black Eye is subtitled, "A Shameful Enlightenment". It's the best of the three volumes. Standfest has a firmer grip on how to combine new and old material and pare down excess. Standfest doesn't worry about manifestos, indulge in fake ads, or otherwise introduce extraneous material; he just gets right down to it. The book is once again a collection of new and reprinted material from other writers and artists. For the most part, it consists of mostly six- to eight-page stories interspersed with repeating single-page gag strips from a few different cartoonists. With a relatively short page count, that allows the anthology to flow in a way the other two volumes did not while helping to strengthen the book's identity.

Standfest's editorial decisions essentially help get him out of his own way and allow the impressive lineup of artists to speak for themselves. The "enlightenment" explored by the artists is often one of an apocalyptic nature. David Sandlin's piece is about the Rapture, punctuated by the most odious aspects of the "prosperity gospel" teachings that emphasize material success as a function of one's spirituality. The "elevator to heaven" winds up leading to a much less desirable place. Johnny Sampson arrives at the same place with an entirely different technique: a set of traditional three-panel gag strips drawn in a bigfoot style. Each strip has a horrifying but hilarious punchline, with the last strip ending with a rapture joke that has the Christians coming to an unexpected fate.

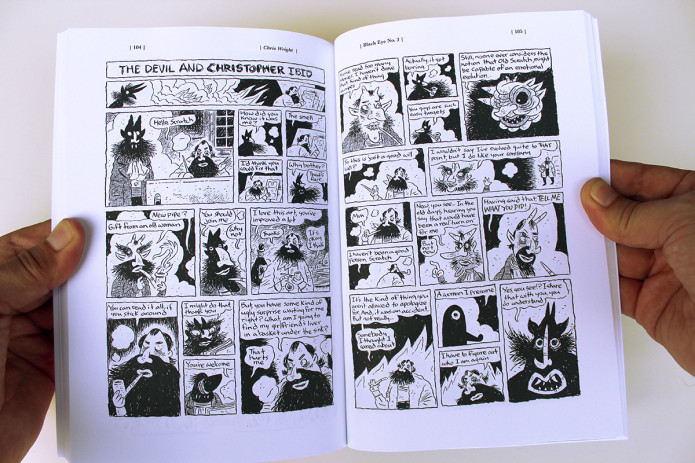

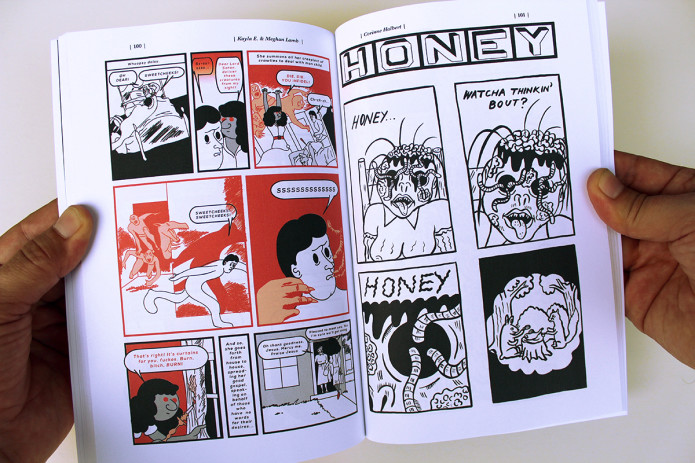

Chris Wright spends a little time with the devil, going back and forth with regard to his own sins, how times have cchanged, and wondering just what Scratch was doing there. The devil teases Wright, eventually revealing the fiery doom that awaits him thanks to corporate greed and other sins. The punchline is worthy of a David Mamet play, and Wright's scratchy, shadowy line is perfectly suited to this cross between condemnation and self-flagellation. Kayla E. and Meghan Lamb's tribute to horror films features a nurse who sacrifices all of her creepy charges to Satan in a story that's both funny and faithful to the genre. The use of a spot color (red) was especially effective in this otherwise black & white anthology.

Chris Wright spends a little time with the devil, going back and forth with regard to his own sins, how times have cchanged, and wondering just what Scratch was doing there. The devil teases Wright, eventually revealing the fiery doom that awaits him thanks to corporate greed and other sins. The punchline is worthy of a David Mamet play, and Wright's scratchy, shadowy line is perfectly suited to this cross between condemnation and self-flagellation. Kayla E. and Meghan Lamb's tribute to horror films features a nurse who sacrifices all of her creepy charges to Satan in a story that's both funny and faithful to the genre. The use of a spot color (red) was especially effective in this otherwise black & white anthology.

Standfest has always had a taste for contributions that wallow in scatology, with Martin Rowson's disgustingly detailed creation story a good example. Here, God is a drunkard whose excrement and bodily fluids of various kinds wind up creating the universe in a highly detailed manner. It's the kind of thing that loses its charm after one page, much less the ten grueling pages the story spanned.

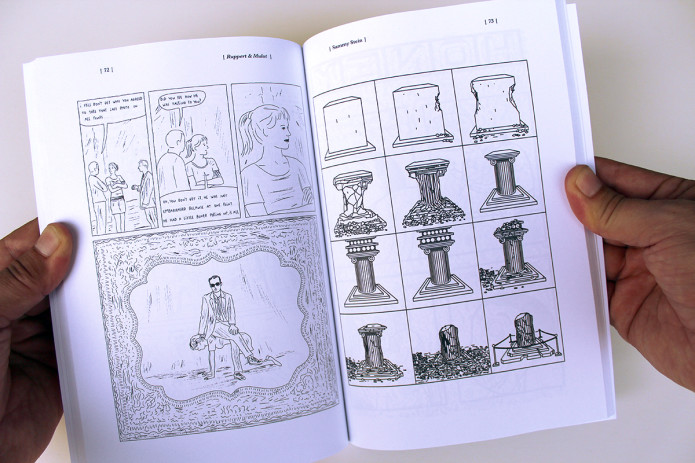

This being the final volume of the anthology, there's a running theme of visceral failure and humiliation, of things coming to a crashing halt. Ruppert & Mulot's story is about an author trying to humiliate the model hired to pose with him for a photo, only for a turnabout in power relations when he gets an erection. Their fine line and small-scale stakes are a marked contrast to the visceral, dense visual approach many of the other cartoonists use. Julia Gfroerer's one-pager about a priest seeking the confession of a "witch" tied down to a bed sees him "overcome" by the evil women's sexual powers, as he's driven to reveal her breasts. Again, it's a case of someone who is in possession of power inadvertently showing how falsely attained that power truly is. John Maggie's power fantasy of building an exoskeleton that reveals his nude body is deflated when two women laugh at his penis, causing it to shrivel.

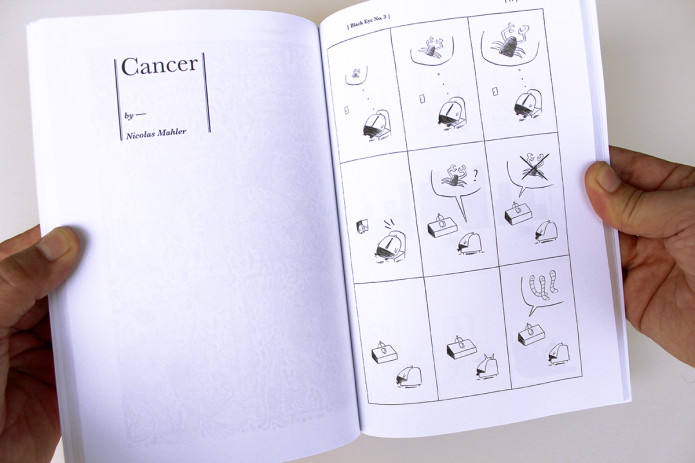

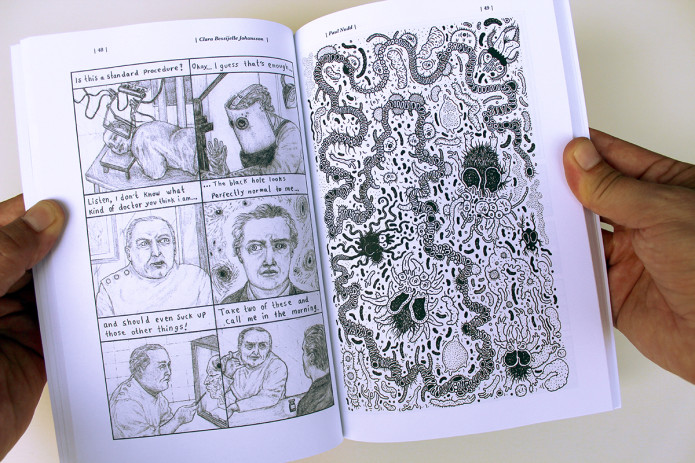

Disease is another running theme. Nicholas Mahler's silent strip about a man expecting to get a diagnosis of crabs from a doctor and instead learning he has cancer is a masterpiece of excruciating slow humor; when he comes home to his wife, there's panel after panel of her bringing him things to the dining table before he finally tells her. Mahler's drawing style is sort of the middle ground of styles found in the anthology: cartoony but rough around the edges. It's visceral without relying on violence or gore. The drawings are funny-looking but serve a narrative purpose. Clara Bessijelle's story about a man who goes to a doctor because he has a black hole in his head is rendered in a naturalistic, feathery pencil style, making it all the more absurd for not only what the doctor sees but that he recommends just taking a couple of pills and calling him later.

Disease is another running theme. Nicholas Mahler's silent strip about a man expecting to get a diagnosis of crabs from a doctor and instead learning he has cancer is a masterpiece of excruciating slow humor; when he comes home to his wife, there's panel after panel of her bringing him things to the dining table before he finally tells her. Mahler's drawing style is sort of the middle ground of styles found in the anthology: cartoony but rough around the edges. It's visceral without relying on violence or gore. The drawings are funny-looking but serve a narrative purpose. Clara Bessijelle's story about a man who goes to a doctor because he has a black hole in his head is rendered in a naturalistic, feathery pencil style, making it all the more absurd for not only what the doctor sees but that he recommends just taking a couple of pills and calling him later.

The "shameful enlightenment" of the collection's sub-title also plays out in terms of guns, violence, and general nihilism. Max Clotfelter's (autobiographical?) piece about enjoying guns as a kid, only to give up his AK-47 in college (one he bought illegally) is bracing in its unabashed love of the experience of shooting, especially when he reveals that he still keeps a couple of guns around. Johnny Sampson's gag about being the only person in a two-page spread nails the insanity of a totally armed, open-carrying society. Onsmith's story about a man who starts to have unrelenting, violent images run through his head runs the gamut from hilarious to deeply disturbing. There's a point where he's confessing these thoughts to someone the reader thinks is a therapist, but in reality, is his boss. The main character basically goes way too far in his descriptions and then doesn't stop. The equation of violent fantasies with stunted emotional growth plays out in that he takes a date to his room, only to show her that he tried to recreate his room precisely from when he was ten years old. When he pulls out a rope, she runs away in terror, to his plea of, "It's for sex, Cheryl! I mean, don't be scared!" This was the most unsettling strip in the book, precisely because its absurdity felt so plausible.

The "shameful enlightenment" of the collection's sub-title also plays out in terms of guns, violence, and general nihilism. Max Clotfelter's (autobiographical?) piece about enjoying guns as a kid, only to give up his AK-47 in college (one he bought illegally) is bracing in its unabashed love of the experience of shooting, especially when he reveals that he still keeps a couple of guns around. Johnny Sampson's gag about being the only person in a two-page spread nails the insanity of a totally armed, open-carrying society. Onsmith's story about a man who starts to have unrelenting, violent images run through his head runs the gamut from hilarious to deeply disturbing. There's a point where he's confessing these thoughts to someone the reader thinks is a therapist, but in reality, is his boss. The main character basically goes way too far in his descriptions and then doesn't stop. The equation of violent fantasies with stunted emotional growth plays out in that he takes a date to his room, only to show her that he tried to recreate his room precisely from when he was ten years old. When he pulls out a rope, she runs away in terror, to his plea of, "It's for sex, Cheryl! I mean, don't be scared!" This was the most unsettling strip in the book, precisely because its absurdity felt so plausible.

Though the anthology is relentlessly bleak, Standfest is careful to include a wide variety of visual styles. The anthology's design is sober and austere, making strips like Eric Haven's absurd entry about the love child of a man and a giant peanut (Mr. Peanut!) especially jarring. Haven's deadpan humor combined with his mainstream superhero aesthetic is quite the contrast to the ratty line of some artists in the book and the ratty line of others. The interstitial material in the anthology is truly the glue that holds it together, providing multiple palate cleansers that allow the longer strips to breathe on their own. Pierre la Police's "The Supremacist" is a series of single-image comics that invoke a superhero aesthetic without actually including genre imagery. The effect is baffling and often funny, as well-design non sequiturs often are.

Standfest also reprints a few iterations of David Lynch's old strip, The Angriest Dog In The World. Every panel is exactly the same in each strip, including an all-text panel that explains that the dog is so angry, it's in a state of rigor mortis. Only a baffling or poetic bit of text differentiates each strip from the others. Paul Nudd's pages are jam-packed with hairy, creeping insects; they give the reader a different kind of resting place for the eye, as his drawings overpower other images. Corrine Halbert's Honey strips take the same punchline (a man's lover having become a maggot-ridden corpse) and tells it slightly differently every time, advancing a story bit by bit. These are raw and grotesque comics. At the other end of the spectrum are Sammy Stein's twelve-panel variations on a theme. Drawn with a clear line and a great deal of negative space, they could easily be New Yorker cartoons. They fit snugly here because they are about entropy and decay leading to an inevitable punchline not unlike Halbert's.

Standfest also reprints a few iterations of David Lynch's old strip, The Angriest Dog In The World. Every panel is exactly the same in each strip, including an all-text panel that explains that the dog is so angry, it's in a state of rigor mortis. Only a baffling or poetic bit of text differentiates each strip from the others. Paul Nudd's pages are jam-packed with hairy, creeping insects; they give the reader a different kind of resting place for the eye, as his drawings overpower other images. Corrine Halbert's Honey strips take the same punchline (a man's lover having become a maggot-ridden corpse) and tells it slightly differently every time, advancing a story bit by bit. These are raw and grotesque comics. At the other end of the spectrum are Sammy Stein's twelve-panel variations on a theme. Drawn with a clear line and a great deal of negative space, they could easily be New Yorker cartoons. They fit snugly here because they are about entropy and decay leading to an inevitable punchline not unlike Halbert's.

Black Eye bills itself as the "anthology of humor and despair," two concepts that go hand in hand. The end is coming for us all, and it's just a matter of how and when. Standfest's contributors laugh in the face of this bleakness, acknowledging its inevitability while defying it with one last gag, one last gross drawing, or one last vicious jab at the horror of the world and its gatekeepers. Standfest trusts his readers more in this volume, allowing the material and his editorial decisions to speak for themselves rather than spelling it out. There's a clarity of purpose and vision in this anthology that sets it apart, as even older material feels fresh and connected to the comics solicited for this issue. This book was published in 2016, yet its bitter laughs feel all the more relevant in a world that becomes more horrifying and absurd by the day.

Black Eye bills itself as the "anthology of humor and despair," two concepts that go hand in hand. The end is coming for us all, and it's just a matter of how and when. Standfest's contributors laugh in the face of this bleakness, acknowledging its inevitability while defying it with one last gag, one last gross drawing, or one last vicious jab at the horror of the world and its gatekeepers. Standfest trusts his readers more in this volume, allowing the material and his editorial decisions to speak for themselves rather than spelling it out. There's a clarity of purpose and vision in this anthology that sets it apart, as even older material feels fresh and connected to the comics solicited for this issue. This book was published in 2016, yet its bitter laughs feel all the more relevant in a world that becomes more horrifying and absurd by the day.