The Swamp, the first volume in Drawn and Quarterly’s ongoing attempt to publish “the complete mature works” of Yoshiharu Tsuge in English, saw the author abandoning rehashed (if nuanced) genre stories to try his hand at more enigmatic, melancholy tales of isolation and sexual frustration. The second volume, Red Flowers, finds Tsuge mining this vein even further, folding in autobiographical details, and subtly exploring more serious, emotional themes.

What might surprise the expectant reader, however, is that the bulk of the stories in this book move not towards the dreamlike, surreal nature of the seminal "Nejishiki", but more towards the meditative regard for nature and the outsiders found at the fringes of society that would arguably find its apotheosis in Tsuge’s final work, The Man Without Talent (1985-86).

Published between 1967 and ‘68, most of the stories in Red Flowers consist of travelogues with a nameless protagonist, an obvious stand-in for Tsuge himself, wandering remote areas of the Japanese countryside, staying at run-down inns and meeting odd or lonely characters.

But let me mention the few outliers first. The most notable one is "The Antlion Pit", a grim thriller about men trapped in a forbidding desert that would be more at home in the first volume, or years earlier in the manga rental market where Tsuge got his start. It is thus no surprise to learn that a) this is a revamp of a 1960 story; and b) it was not done for Garo but a more mainstream comics magazine (though it is a bit of a surprise to learn that this story is inked by none other than Ryōichi Ikegami of Crying Freeman fame). It is wisely placed at the end of the volume so as not to disturb the mood of the rest of the book.

In the other initial stories, themes of isolation and melancholy start to emerge. They also start to reject definitive endings and simply come to a quiet halt, more interested in setting a scene or introducing a character than evolving a plot. The title character in "The Salamander"–easily the darkest tale in the book–doesn’t recall how he ended up in the fetid sewer that is his home. And though he describes being unhappy and ill at first from his new living quarters, he nevertheless finds an eventual peace and contentedness over time, preferring solitude and the discovery of peculiar objects, including a dead fetus.

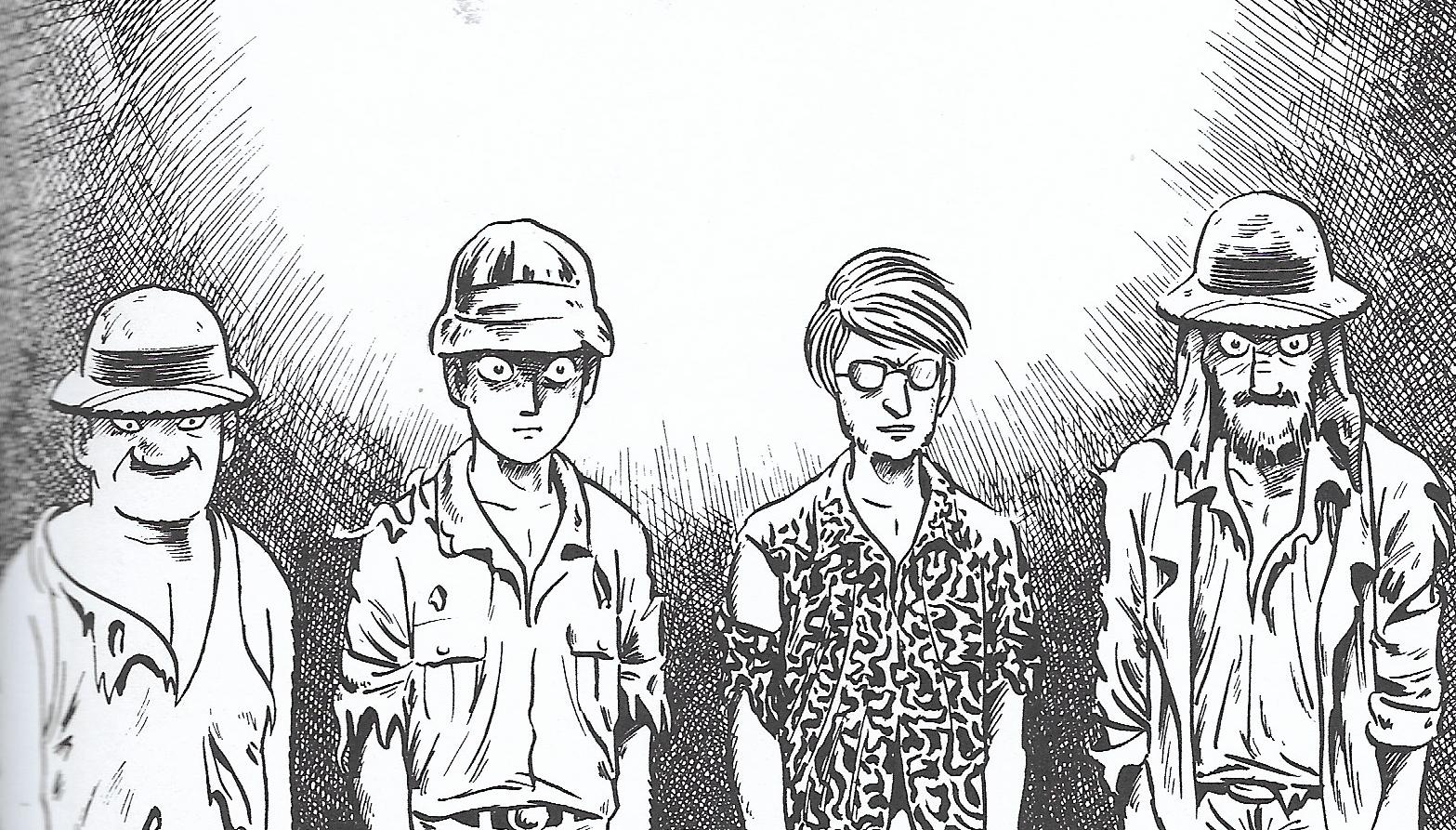

In the "The Lee Family", a man takes over an abandoned rural home, only to have a strange family move in upstairs, intruding on his “elegant paradise.” The wife and young children are silent and eerie, while the husband is “lazy” and broke, a draft rendition perhaps of the title character in The Man Without Talent. Perhaps the most striking thing about this story is the grim rimshot it ends on, with the family all staring out of the window directly at the reader, daring (or perhaps imploring?) them to show either scorn or pity - apparently this ending was so sudden and unnerving that some cartoonists actually attempted to make unofficial sequels.

But it is in the fifth story, "Scenes from the Seaside", that the pattern emerges. Here we first meet our Tsuge-like traveler, this time visiting the beach, and awkwardly flirting with a young female visitor. Tsuge puts his all into delineating the large ocean waves, ominous cliffs and throngs of suntanning tourists. This work is most evocative in a stunning final two-page spread where our hero attempts to swim through the surf to impress the lady, both characters silhouetted against dark clouds and a forbidding rain, dwarfed by the ocean.

From then on, the crowds thin out as our nameless protagonist starts venturing into more rural areas (apparently these trips mirrored Tsuge’s own travels during this time period). Perhaps vexed by the rapidly modernizing Japan and the technological onslaught of the late 20th century in general, Tsuge’s man seeks out inns that, to put it politely, have seen better days (at one point he asks to be directed to “the shabbiest inn”). Once there he usually comes across an eccentric or elderly character that calls to mind a vanishing past or just the general sweep of time. There is a romantic and perhaps even mawkish sensibility at work here, but Tsuge manages to deftly belie that through his empathy for the hapless people (and animals) he comes across, and through his sense of awe at the surrounding environment.

Take, for example, "The Incident at Nishibeta Village", where our hero, who has come to a remote area to fish, learns that “a nutcase” has escaped from the nearby mental hospital. A mob of locals form to find him, fearful of some murderous (or lascivious) madman on the loose. After a frantic, fruitless and comical search, our man discovers him by chance - not some dangerous lunatic but a hapless young man just as ill at ease with the world as the rest of us.

There are others. The lonely innkeeper in "Mister Ben of the Honyara Cave" whose gruff, stoic exterior hides sorrows that extend beyond a general lack of customers. There’s the old man in "Chohachi Inn", a former fisherman stuck on dry land due to a bad injury. Even the banana-stealing monkey seen in "Futamata Gorge" elicits sorrow and sympathy when its life is imperiled due to a bad storm.

While not as dark and foreboding as in the title story of The Swamp, there’s also an undercurrent of sexuality, specifically female sexuality, lurking in many of these stories. There’s the aforementioned romantic interest in "Scenes from the Seaside", and the indifferent wife in "The Lee Family", but there’s also two women in "Chohachi Inn", one of whom posed nude (albeit from the back) for the inn’s brochure. And in the titular story there’s a poor young girl, going through what appears to be a painful (and possibly her first) menstrual cycle, forced to work in place of her drunken father. In Tsuge’s stories, sexuality and desire are primal forces, no different in their consumptive power than the ocean in "Seaside".

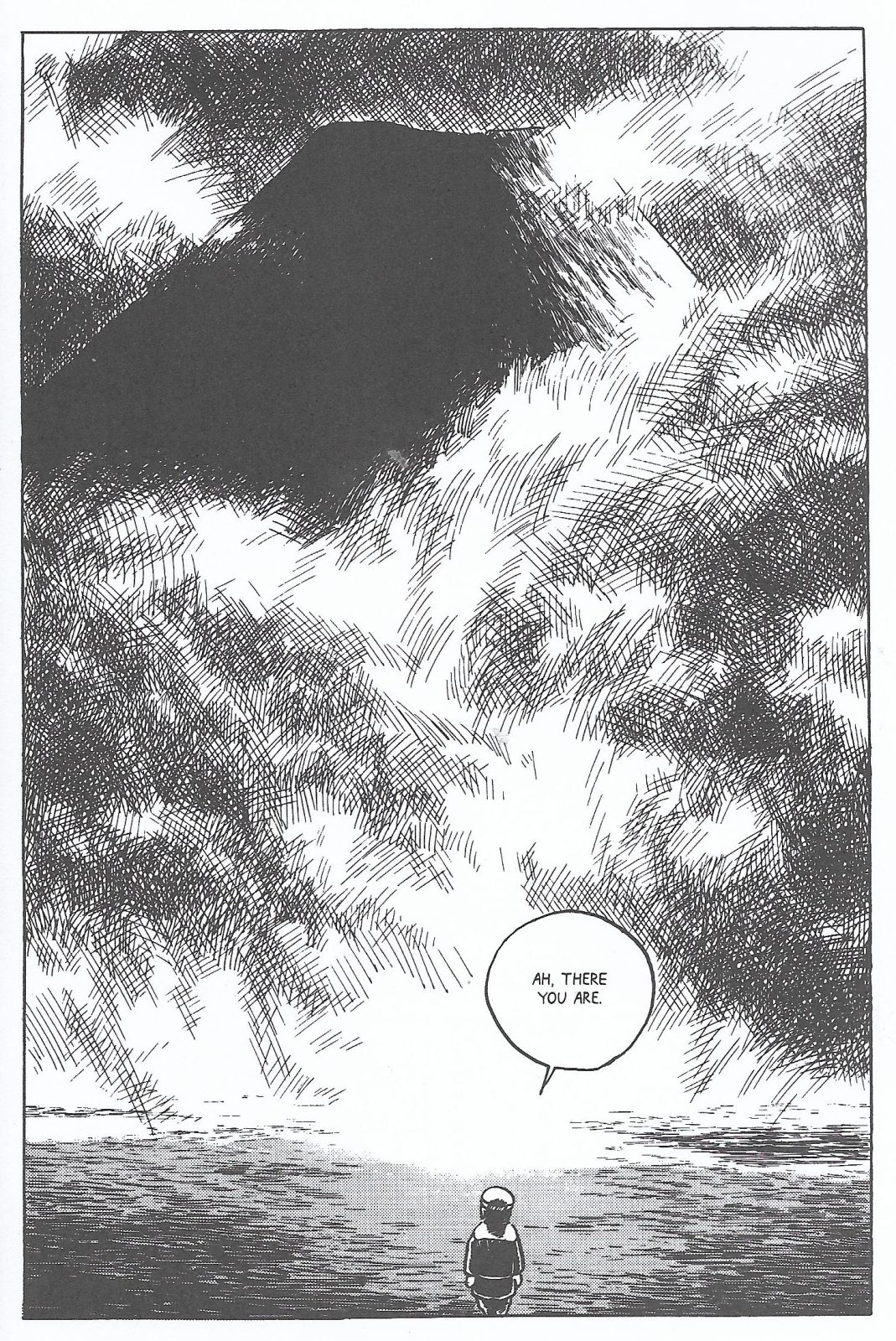

I can’t speak enough about Tsuge’s stunning depictions of the natural world and its inhabitants. Despite drawing upon photographic references (an idea apparently influenced by his time spent working as an assistant for GeGeGe no Kitarō creator Shigeru Mizuki), his lavish, sublimely detailed depictions of forest trails, crumbling huts and rushing streams never seem like mere tracings or staid copies, but rather a vibrant world that both entices and threatens, as when, at the end of "Chohachi Inn", Mount Fuji appears through parted clouds, filling the entire page in a manner both majestic and unsettling.

In a lengthy essay at the back of the book, series co-editors Mitsuhiro Asakawa and Ryan Holmberg state that these stories are “some of the most important works in Japanese comics history.” That might well be (and the pair make a compelling argument), but for this Western reader, the historical significance takes a back seat to the unique and singular voice on display. Now with this third Tsuge volume available (counting New York Review Comics' release of The Man Without Talent), we have a more complete picture: one of an artist uneasy with the surrounding world, in awe of what lies beyond his urban borders, suffused with sympathy for those who, like him, have found it difficult “getting by”.

In "Mister Ben of the Honyara Cave", an innkeeper asks the traveler why, if he’s not making any money, he continues to ply his trade as a cartoonist. “It’s all I know,” the traveler responds. Even all these generations later, we are lucky that Tsuge knew so much.