Pulp, the latest collaboration between Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips (with coloring by Jacob Phillips, who only gets better with each project), is a rather typical work for the pair. Despite the new-ish format, a one shot graphic novel that is not tied to their previous Criminal stories, it has a lot of the same virtues of their older comics: rock-solid storytelling, keen grasp of genre limitations (and how to break them) and interest in ideas that go beyond the boundaries of the plot. Sadly, it also shares their one major weakness: they don’t know how to end things.

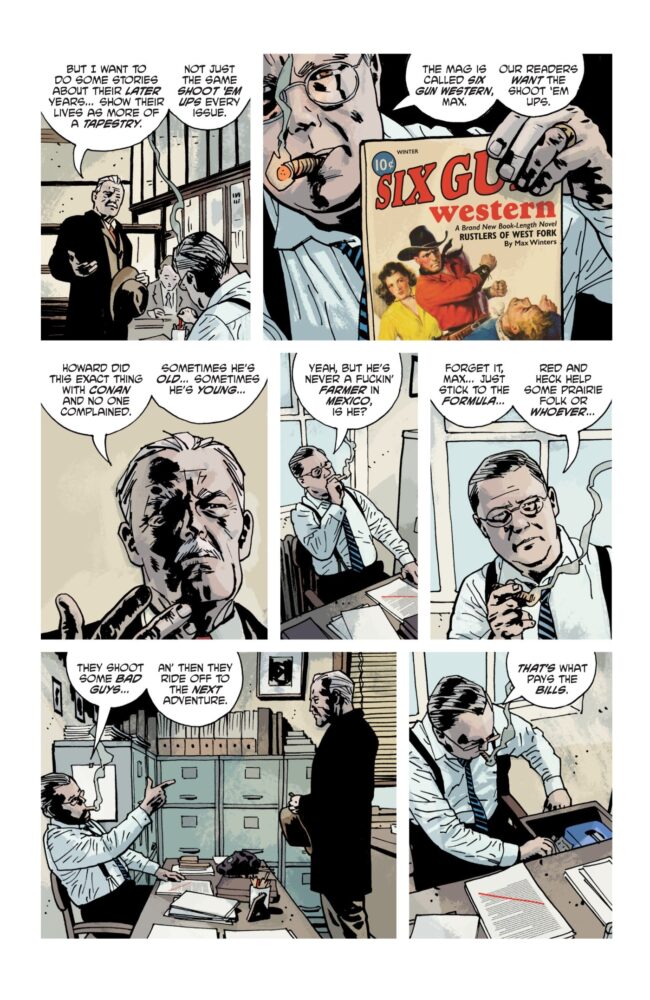

Oh, for sure, they end things well enough on the story level, all the plot threads are tied satisfactorily enough, every character gets its due; but on the level beyond sheer plotting Pulp remains unsatisfying. The graphic novel points at many interesting ideas, the way history is whitewashed through popular culture, how the comics market inherited its morally bankrupt business model from the pulp magazines, America’s oft-ignored embrace of the Nazi party etc. Yet it can never quite manages to make anything cohesive out of any these notions, let alone tying them all together. It is as if the creators believe that by merely pointing at important issues they engage with them.

This isn’t a first-time thing with Brubaker and Phillips. The Fade Out, another historical noir team-up with a lot of meaty issues in mind, ended in a way that ticked all the right boxes while leaving you wanting more, as if the real final step is missing. Criminal, their most successful team-up, works precisely because there is no end. It’s a series made of middles: dropping in and out of characters and timelines to indulge whatever is on the creators’ mind, engaging in process rather than conclusions.

Brubaker and Phillips’ most esteemed competition in the world of crime comics, the ever reliable David Lapham, doesn’t pretend he’s making some grand thesis statement on American culture. Stray Bullets is content to let the cruelty of criminals play out on the page and let the audience draw whatever it desires from it – be it sick pleasure or deep rumination (or any combination thereof). Pulp isn’t satisfied with just being a cool caper, it wants to be something more.

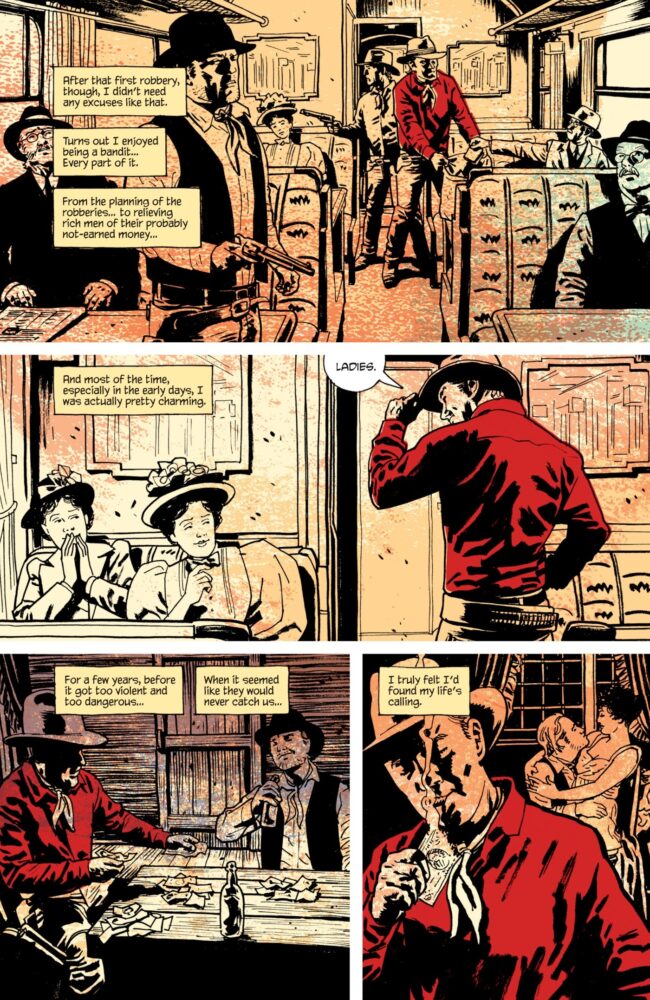

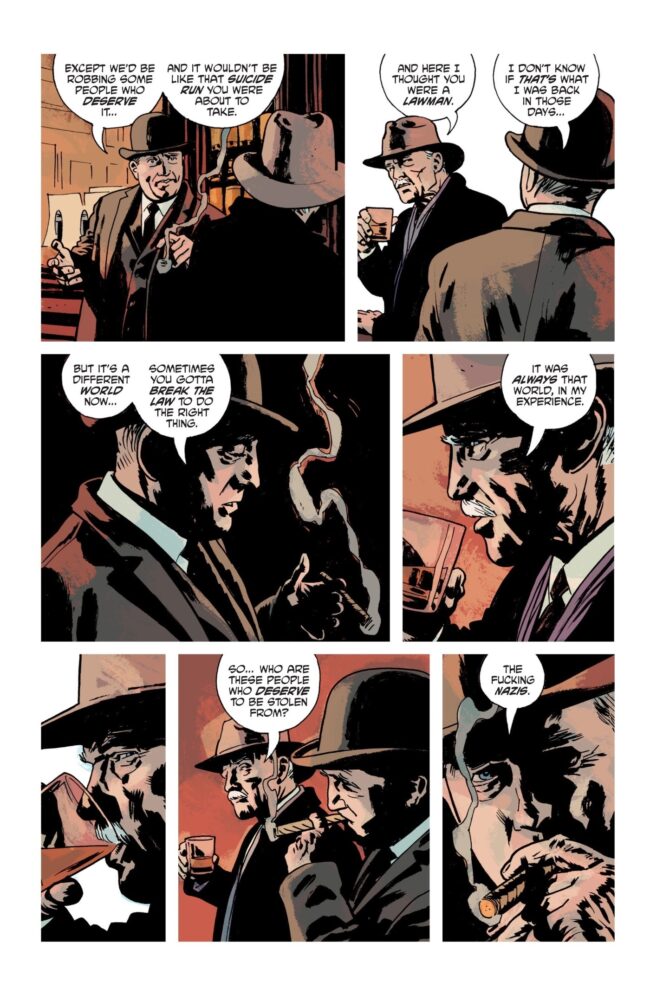

Pulp tells the story of Max Winters (that’s a good name, Brubaker was always solid with protagonist names), an aging writer in 1930’s making ends meet on two cents a word for western pulp magazine. What his editor doesn’t know is that all of the daring do Max is so good at describing is less fiction and more history – based on Max’s hidden life as an outlaw in dying days of the wild west. Now, on death’s door and with no retirement funds to call on, he’s got to pull one last job if he wants to ensure the fate of the woman who loves him. That job? Robbing the fucking Nazis!

This is a fine idea. Seeing Nazis robbed, and beaten and shot and all that other stuff, is still pretty nice. It is also obvious that the choice of that particular target is aimed squarely at the present. As Winters’ partner, Goldman, notes: “We see it in the newsreel like it’s some distant thing that’ll never touch us… but this hate, it’s here, too, Max.” Though I am about to be unkind in the following parts of the review I want to make it clear cut that Pulp is actually a fun read, something I write without commas of any kind or ironic distancing. It’s paced well, it’s surprisingly dense for its slim size, Sean Phillips get to draw grown men in suites smoking cigars... the good shit.

Some of the best stuff in Pulp is the cowboy parts, which kinda make me want to see this team just doing a straight up western. Whenever we get a glimpse into Winters' stories Phillips lets go of his natural style in favor of something more heightened. The pencils grow sharper, the figure-work bolder, the movement is clearer. This, again, helped immensely by Jacob Phillips coloring which becomes almost free of shading in favor of high contrast helps the characters pop on the page in a way that makes the rest of the graphic novel feel overtly mannered. I get it, there's meant to be a contrast between the 'dull' reality and the 'exciting' fiction; but this is a caper comics about an old cowboy robbing Nazis - why insist on being unexciting when you can go for broke?

At this point in their career these creators know this stuff inside and out. You can grumble that they don’t surprise you, but do you read the next Ed McBain or Donald Westlake novel trying to be surprised? Of course not! The regularity does not necessarily denote lack of artistry, simply a level of professionalism in one’s craftsmanship.

There's a certain rigidity to these pages, which appears intentional. Phillips always seems to put the characters at the center of the panel, and for all his much-vaunted atmospheric shadows this is basically old-school storytelling: show the reader what is necessary, but keep things moving. There's hardly ever a silent panel, as if Brubaker cracked the secret noir comics code of how many caption boxes could there be at each page. Pulp is very novelistic and yet the text never crowds out the art, it never overwhelms the page. You've got to be good to pull this type of thing over and over again without becoming dull. There's a whole lot of talking in this comics: conversations, monologues, infodumps... but it never feels like it until you stop and think the pages over. Phillips' page construction knows how to keep it in the right groove.

The problem begins when Pulp starts trying to engage on an intellectual level, to make some grand statement about the meeting of the genre and reality. As it reaches its climax Pulp turns out to be nothing more than an update of its own influence, with a knowing wink attached at the end. The book ends with violence, the righteous kind in which the one good man stands up to evil – with a six shooter in hand (almost) and justice in his heart. The violent, but necessary, acts of the one good man is what it takes. Early on in the story we witness Winter’s bitterness as his editor forces him to keep his character (i.e. himself) alive to have another thrilling adventure in the next issue. Just like Max himself is forced to continue mining his own past in the form of cheap entertainment way past the age of retirement; just like the comics market (descendant of the selfsame pulps) kept the same old characters in circulation for decades. No one gets to retire.

Which is why the end of Pulp feels unsatisfying. It gives you exactly what you expect, without challenging you in any meaningful way, while providing the illusion of challenge. It doesn’t really engage meaningfully with American hate, be it historical or modern. It gives you a momentary pleasure in seeing the perpetrators dispatched in a hail of gunfire, but nothing beyond it. Can't we ask for more from a decent pulp story?