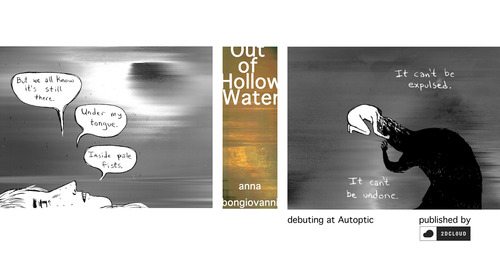

Anna Bongiovanni's debut book, Out of Hollow Water, is one of the better and more startling debuts I've seen in the last decade or so. Her work is an exemplar of a style of cartooning that's dense, dark, scratch,y and unflinching in its willingness to confront pain, trauma and horror. The obvious comparison for Bongiovanni is Julia Gfrorer, who in fact blurbed this book. They tap into different emotional and psychological veins in their work, even if their styles and rawness are similar. Both frequently make comics set in a timeless, nameless forest environment where darkness and the supernatural are real, lurking concerns; it's just that the two set their comics in different parts of that same, primal forest.

Out of Hollow Water explicitly deals with the trauma of violation, as well as the reality of surviving that trauma, in each of its three stories. While Bongiovanni has noted that these comics are personal and a way of working through her own issues, she's also careful to make the stories vague enough that one can fill in any number of blanks as to both precisely what happened and what each person is doing as a result. That's where using a fantasy/mythological setting makes so much sense, because it provides a buffer between real life while simultaneously creating a larger-than-life sense of dread and even suffocation on the page.

Each of the three stories can be read as entirely separate entities. They can also be read as loosely sequential, representing violation, the consequences of the violation, and attempting to cope with that violation. The first story, "Monster", is a first-person dialogue illustrating one woman's account of being violated by a monster. That violation can read as sexual, emotional, and/or psychological, and Bongiovanni makes the first reference in the book to "pretending": "All I can do is pretend not to notice your shadow just under the surface." Bongiovanni conveys the disorientation of the experience by throwing a different point of view at the reader in every panel: a woman pinned to the floor by a monstrous shadow creature, the shadow becoming her own shadow as she slumps to the floor, the woman narrating her story to an unseen listener. The story ends with a series of fragile drawings on grey paper that show various ways that the experience has warped and mutated her, both in fantasy terms and in terms of self-perception. One of these depicts her as being pregnant with a disgusting, tumorous object.

That leads directly to the title story. Bongiovanni brings the tension in this story to an almost unbearable pitch, thanks to a simple story device. In a cabin in that nameless forest, a child is born to a young woman (who may or may not be the woman from the first story; her hair color is different) and given to her younger sister to dispose of. The young girl protests, but is told in no uncertain terms that the baby doesn't belong "in the cave, like the rest". The older woman who's commanding the young girl notes that she needs to do this so that they can "pretend none of this happened", the second reference to denial in the book. Of course, given the flat, expressionless face of the young woman who gave birth, that will be easier said than done. For much of the book, Bongiovanni uses a single panel per page in a book that's 6 x 6" square. In this story, when we see the young girl defy her orders and make a long trek through the forest goes to a six panel grid to speed the reader along and then switches back to single-page panels on pages where she wants the reader to linger on images that ratchet up the tension.

That tension, of course, starts with the girl feeling the instinct to protect what is an innocent life from being murdered, especially since she's the instrument of that murder. At the same time, the reader knows that the child is the result of a monstrous union and possibly a supernatural or demonic rape. All the reader knows is that there's a Good Reason why the child needs to be drowned in a nameless well, never to be heard from again. So the reader can't help but feel for the young girl defying orders even as we know something terrible is going to happen if she disobeys. Sure enough, something terrible does happen: a monstrous, shadowy female creature follows the girl's trail to the well. What she does with the baby is unclear but obviously horrible. It's a story about innocence being repaid by brutality. about there frequently being no easy or palatable answers to a difficult situation, and the ways in which mercy can be exploited and betrayed.

The final story, "Grave", appears after some haunting images of a mutated/mutating baby/fetus once again appearing on grey paper, this time drawn with a tattered white line. It adds to the haunted, spectral quality that runs through the entire comic, as though the reader is witnessing something they really shouldn't see. "Grave" is told in second person, as the unseen narrator gives commands to the figure on the page. This story is about the consequences of trauma as well as the consequences of pretending it never happened. Once again, a young woman returns to a spot in a nameless forest, a spot where she buried a box filled with shame, regrets, fears, nightmares and memories. Her face is never seen until she disgorges a pinkish goo of negative feelings and memories into the box, and even then, her entire head is subsumed by that goo. We see brief flashback panels hinting at horrific childhood memories; just enough for the reader to get a glimpse of understanding what's going on. Like the other stories, there's no definitive conclusion here; we're told "You feel lighter. Almost in control", but this goes back to pretending once again. We are left with several pages of still water that may or may not have shadows lurking within them.

In Bongiovanni's stories, no one is let off the hook, least of all the reader. Though they bear some resemblance to actual fairy tales designed to scare children, stories without happy endings, Bongiovanni undercuts that by providing no lesson. Horrible things simply happen to people, and there are particularly horrible things that can happen to women and children. There's nothing cheap or exploitative about the images that she uses. Indeed, the book creates its tension because of her incredible restraint as a storyteller. In that restraint, one can feel the power and fury in her line, lurking in the stillness of quiet imagery that quickly flashes to the awful, the unforgettable and the unthinkable.