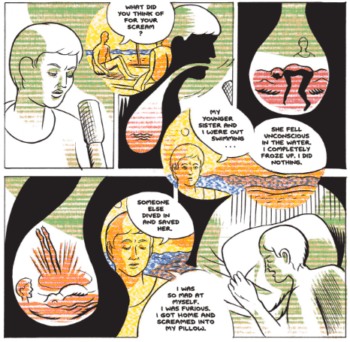

Three issues into Now, Fantagraphics’ flagship, triannual anthology, and we’re three for three on stand-alone Dash Shaw comics. Shaw’s comic here, “Crowd Chatter,” finds him layering streaky blobs of colors and patterns and an idiogrammatic X-ray technique atop his thick line. The X-ray trick exposes experiences the characters have absorbed, experiences just lurking deep inside their guts. As with all of Dash’s comics, the dialog is naturalistic and note-perfect. The story is nine pages and is perfect for this anthology. It’s funny, topical, and visually inventive. The more time you spend with it, the more depth is revealed in its swirl of consumption, repressed trauma, and the ways in which larger real-world events can get under your skin and impact your life. I’m sure there won’t be a Dash Shaw comic in every new issue of Now, but there should be: he’s the perfect cartoonist for this anthology.

There are no genre thrills in Now and there is nothing gory, titillating, or macabre. Characters wrestle with trauma, but there isn’t actually much violence depicted. There is little that is overtly political and there are no obvious thematic through-lines which run through individual issues. The anthology’s direction is less focused on thematic coherence and more on exhibiting the widest variety of techniques for expression in the medium. Some comics tell a story with a more traditional literary narrative like Roberta Scomparsa’s “The Jellyfish”. Others experiment with the formalist components of comics like Jose Ja Ja Ja’s “Grand Slam”. And still others do something completely unique like Keren Katz’s “My Summer at the Fountain of Fire and Water” which foregrounds the motion and posture of characters in a modern dance, cartooning amalgam.

Variety of technique is one way Now differs from Mome, Fantagraphics’ previous anthology series, which ran from 2005-2011. Mome was square-bound, more expensive per issue, and proudly embodied the expectations of the traditional book store market. It had comics by best-selling memoirist David B. and cover art depicting scenes either domestic or somewhat enigmatic – someone playing an instrument or feeding pigeons. At least that was my memory of Mome. Reading through again recently I realized I had turned it into a bit of caricature and it hadn’t been nearly as staid as I remembered. There were all sorts of different cover-art mixed in with the ones I remembered, and one with full-frontal male nudity. There was depth in the variety of the comics it ran, most of which were from young cartoonists. And there were definitely no shortage of experiments with form. Gabrielle Bell, Tim Hensley, Josh Simmons, John Pham, and even a young Dash Shaw all had major work published in Mome.

Variety of technique is one way Now differs from Mome, Fantagraphics’ previous anthology series, which ran from 2005-2011. Mome was square-bound, more expensive per issue, and proudly embodied the expectations of the traditional book store market. It had comics by best-selling memoirist David B. and cover art depicting scenes either domestic or somewhat enigmatic – someone playing an instrument or feeding pigeons. At least that was my memory of Mome. Reading through again recently I realized I had turned it into a bit of caricature and it hadn’t been nearly as staid as I remembered. There were all sorts of different cover-art mixed in with the ones I remembered, and one with full-frontal male nudity. There was depth in the variety of the comics it ran, most of which were from young cartoonists. And there were definitely no shortage of experiments with form. Gabrielle Bell, Tim Hensley, Josh Simmons, John Pham, and even a young Dash Shaw all had major work published in Mome.

The comics in Now do look different than the ones in Mome, but the difference has more to do with the changes in taste of the new generation of cartoonists than in any editorial direction. Dan Clowes and other 90’s alternative cartoonists’ influence were felt all across Mome, but they're practically non-existent in Now. Both thematically and stylistically the influence of the big Alternative cartoonists has receded as a dominant force. A comic in Mome like Paul Hornschiemier’s “Life With Mr Dangerous”, with its listless protagonist muddling her way through bad relationships, a dead-end job, and self-loathing felt like a relic on a recent re-read. It’s likely that no cartoonists with work in Now would list Peter Bagge as an influence, but he was clearly a major one for Kurt Wolfgang’s comics in Mome, with their rubbery armed characters getting into mischief and lazing about. There is little self-loathing in any of Now’s comics, and Now issues #1 - #3 might contain the least amount of cross-hatching of any non-genre comics anthology series published in the last 40 years. The one thing Now is best at is showing exactly how much the comics canon has been blown open in the last ten years.

Now also has more than a few translated comics. Some of the artists, like France’s Anne Simon, Israel’s Keren Katz, and Germany’s Anna Haifisch are contemporary cartoonists that already publish in English, have a presence at North American comics festivals, and generally fit in with the contemporary focus of the anthology. But each issue has also had at least one translated comic that doesn’t fit in with that particular editorial direction. Issue #1 of Now had work from J.C. Menu, a foundational figure in French alternative comics. Issue #2 had a Brazilian mini-comic originally published in 1998 by artist Fabio Zimbres. And now Issue #3 has a comic from another Brazilian artist, long-time comics professional Brazil’s Marcello Quintanilha. Quintanilha has been published by Casterman and various Brazilian publishers over the last 20 years, but his work had never been translated into English. His short comic in Now #3, “Sweet Daddy”, doesn’t look like anything else happening in North American English speaking comics, but it's professionally mature work. One small panel depicts an office scene with people sitting around at five or six different points between the foreground and the back. It’s no joke to have that type of casual depth in a non-showy way. You only get that good if you have done this for years professionally.

Now also has more than a few translated comics. Some of the artists, like France’s Anne Simon, Israel’s Keren Katz, and Germany’s Anna Haifisch are contemporary cartoonists that already publish in English, have a presence at North American comics festivals, and generally fit in with the contemporary focus of the anthology. But each issue has also had at least one translated comic that doesn’t fit in with that particular editorial direction. Issue #1 of Now had work from J.C. Menu, a foundational figure in French alternative comics. Issue #2 had a Brazilian mini-comic originally published in 1998 by artist Fabio Zimbres. And now Issue #3 has a comic from another Brazilian artist, long-time comics professional Brazil’s Marcello Quintanilha. Quintanilha has been published by Casterman and various Brazilian publishers over the last 20 years, but his work had never been translated into English. His short comic in Now #3, “Sweet Daddy”, doesn’t look like anything else happening in North American English speaking comics, but it's professionally mature work. One small panel depicts an office scene with people sitting around at five or six different points between the foreground and the back. It’s no joke to have that type of casual depth in a non-showy way. You only get that good if you have done this for years professionally.

The weakest link in Now #3 is the cover. Al Columbia turns in a painting that exhibits his impeccable draftsmanship with more dead-eyed citizens shuffling down the street on their way to or from their jobs. It’s a thoroughly rinsed metaphor. How much longer are we going to have to see the average white-collar salaryman get dragged by artists? The cover feels out of step with the rest of the anthology’s contemporary relevance. Now is beholden to younger cartoonists who are more likely to comment on the lack of work or decent pay than to criticize people who do have jobs. There certainly aren’t any other pot-shots at office-worker drones on the inside of the anthology, and I have to admit to feeling conflicted between my initial objection to the cover and a bit of nostalgia for spirited comic art, delivered at the expense of pitiable squares.