She knows her life is horrible. There is a life she wants, there is a life she thinks she wants, and there is a life that others want for her. Her life is none of those things. She would call it crud. Every single day something is deeply wrong. She knows this and grieves it but in her mind she rejects it. She tells herself every morning that today will be when it all becomes great, like it’s always supposed to be. She won’t be horrible. Her friends won’t be horrible. Her life won’t be horrible. She’ll have a boyfriend and he will not be horrible. Every evening she tells herself it’s started happening and it will happen for real tomorrow. Because it didn’t happen. It never happens. She can’t bear to admit to herself that she hates herself, and yet the only reason she hates herself is because it’s less scary for her to be the problem than to acknowledge that cruelty surrounds her, that her life is pain inflicted on her. It’s not a horror story. This is a comic about what it’s like to be a kid.

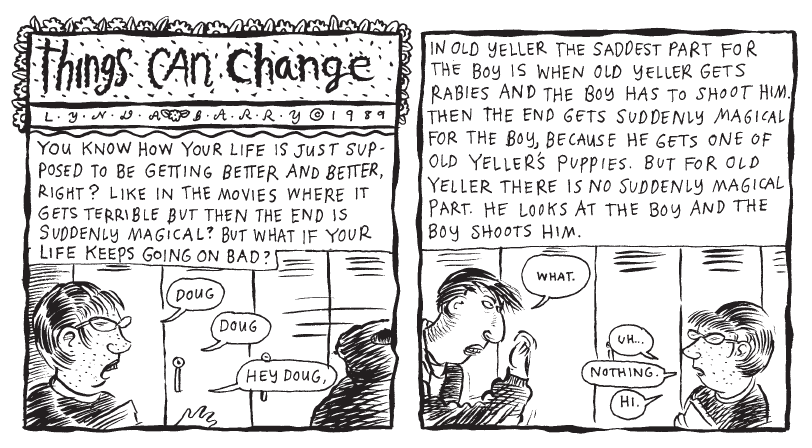

The back pages of My Perfect Life inform the reader that the graphic novel collects comic strips from Lynda Barry’s alternative weekly strip Ernie Pook’s Comeek from 1990-1991, bisected by the short story “The Most Obvious Question” which appeared in RAW in 1991. (Not noting, mind you, that this hardcover release from Drawn & Quarterly reprints a Perennial collection from 1992). The back cover tells another story about the work’s contents, as spoken by Barry’s characters in the voice of young Marlys, her older sister Maybonne, "the star of our show," stepping in only briefly to shyly whisper in her ear. Marlys tells the potential reader:

"This book’s about my sister. About her incredible life and opinions. [...] [T]his is a personal book about her life. Really personal. Could blow your mind."

Marlys’ words speak truthfully to the comics held within, only hinting at the painful intimacy of Maybonne’s “incredible life and opinions” with a small comment that Marlys will be watching over Maybonne, protecting her. These comics are indeed really personal, an overwhelming descent into the crummy life of a teenage girl and the desperate and beautiful stories she tells herself. Each strip’s panels are divided into two sections: up top, lengthy text captions derived from Maybonne’s diary (or letters she’s written), and, down bottom, illustrated narrative scenes of her life that follow, digress from, and undercut her written account. It is a testament to Barry’s craft as a cartoonist that both halves of her story are visually compelling - the length of the narration does not drown out the art but wonderfully captures the anxious over-excited inner voice of a kid who needs to tell huge stories to make their life grand and beautiful in the face of a small and joyless existence.

Maybonne is frustrated. Her town is miserable, school is crushing and dull, she is socially outcast, and her home life with her sister and grandmother is stagnant and claustrophobic. This is the year that Maybonne begins to notice boys - like, really notice them. It’s also the year that girls start to suspect she’s gay and avoid her, then suspect she is stealing people’s boyfriends and avoid her, adding juvenile sexual layers to their arbitrary-yet-obsessive cruelty towards an awkward, freckle-dotted pimply bespectacled girl who could never fit in with the rest. It’s also the year that boys start to notice that Maybonne is free, available and desperate, “easy.” Maybonne finds herself frustrated, “experienced,” disappointed, alone, eager, tossed around at the whims of destructive pubescent egos and left with only the promise in her heart and the entries in her diary, where she reminds herself that everyone is good deep down and that she should be able to love everyone.

Maybonne’s diary is out there, man - peace and love and hope for the entire world blossoming at once. The cracks in her worldview begin to show, not only in the images where we see her awkwardly stumble and hear the rumors whispered when she isn’t around, but in her own private words, which turn sour as the gulf between what she wants to be and what she lives and feels day after day widens further and further. “Most of all I just wish for everything about me to change. And then I swear to God I would quit acting insecure, and be myself,” Maybonne writes, “like in all those songs where people are being themselves.” That hopeless, disappointed, angry turn is devastating to read. On their own, the strips are funny, relatable and compelling. Collected, they are tragic and painfully recognizable, capturing that moment in any young girl’s life when she realizes everything is wrong and can hardly bear to admit it, and in that denial looks within to torment herself with whatever personal failing she can put into words, whatever self-loathing she can bear to believe rather than truly feel her hurt.

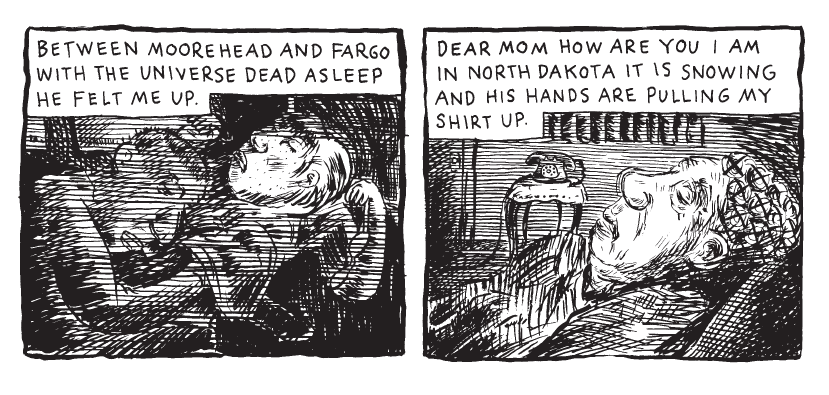

And then there is the longer story, the RAW story (in more ways than one), “The Most Obvious Question”, which casts Maybonne in a grimmer, more melancholic register than the four panels of space in an alt weekly could allow. In this story, Maybonne takes a Greyhound to visit her estranged mother, who does not love her. A charismatic young man, far older than she, talks Maybonne into leaving the bus with him, and then sexually assaults her. The reader follows Maybonne’s dissociated recollections: of her parents abandoning her and her sister; of her grandmother’s sharp contempt for her; of her lonely ride and the horrible experiences inflicted on her. Barry provides exceptionally elegant cartooning and gentle hatching, Maybonne’s dissociation presented to the reader as a moonlit abstraction of pain, providing the kindness and compassion that nobody could truly provide Maybonne when she lived an unbearable trauma.

Following this sobering, difficult narrative, the strips follow at an ever-chipper, manic pace, returning us to lighthearted and literally brighter cartoons full of loose drawing, smaller problems and open spaces. One of the last stories told the collected strips, in which Maybonne’s callous, cheating ex-boyfriend returns for her born again as a Jesus Freak, is easily the funniest in the book. It’s a jarring juxtaposition, but that juxtaposition is clarifying and I would argue gives the book a greater shape beyond the year of comics it presents in order. Childhood and early adolescence is a time of such great pain. We remember our youth in idealized terms, but horrible things happen to us, all of us, before we could ever know how to describe them. Many of us forget for a long time about the days we spent wishing from the moment we woke up that we could cease to exist, wondering why nobody really loves us, why it all went wrong and if it could ever get better. We forget because when we were little we didn’t have the words to understand or believe what we felt; like Maybonne, we imagined vast and creative rationalizations that could reveal the beauty of our inner world just as much as they could bury our bitter truths. We all led a Perfect Life like this, whether we liked it or not, because school as we knew it was designed to make sure we did.

And yet, these are not horror comics. These are humor comics, comics about the daily life of a normal girl, even with one literary story quietly crying out the unspoken pain implicit among the rest. Maybonne has a gorgeous mind. She is funny. Her life is funny. The things she says are funny. Everything about her is funny, and also beautiful and true. Her strength shines through every wretched cruddy moment as she ties it all back into her ridiculous, idiosyncratic and eternally upbeat worldview, writing optimism and comedy into even her most unvarnished moments of self-loathing and sadness. Her stubborn insistence of telling her frustrating, all-too-mundane grief-stricken life story on her own inventive terms allows these comics to be funny, and allows the reader to read these stories with a knowing smile on her face. More than all her familiar agonies, it’s that happy, simple feeling that Maybonne pushes both herself and the reader to feel that makes these comics “really personal,” an honest depiction of what an adolescence like hers is like. Despite everything, Maybonne’s life really is perfect. It’s perfect because it’s hers.