As much as I tend to joke about it, I'm not actually all that old a guy, though I'm at the point where generational differences become increasingly acute. For example, I quite vividly recall a time when access to the works of Alejandro Jodorowsky was partial at best, and restricted to those knowledgeable about gray-market tape trading and moldering back issues of Heavy Metal. My younger friends cannot recall this era, as it has been defunct for the better part of a decade; this year alone we are guaranteed English translations of the remainder of Jodorowsky's expansive work in the shared universe of The Incal -- concocted with the late artist Moebius in the early 1980s -- as well as wider releases for two newish feature films: one a documentary, Jodorowsky's Dune, premised on the abortive Frank Herbert movie adaptation which ultimately wound up powering Jodorowsky's writing career in BD; and The Dance of Reality, the first directorial effort by the man himself since The Rainbow Thief in 1990.

There is, of course, a gulf in visibility between these two films – and in a rare twist, it's the documentary that seems to have found faster, wider distribution, with all accordant boosts in media discussion. But then, conceptually, it is a celebration of nerd lore, centered around a movie that was never made, which means it can exist eternally as a manifestation of pure hype; not a bad result for Jodorowsky, a longtime signatory of Artaud's notion of imagination as reality, and a circus man to boot. But conservative me looks lamentably toward the other, which, despite being a finished work of the living, breathing artist at the front of the documentary, is apparently bereft of the geeky genre hooks necessary to sustain obsession, unless one considers a notional similarity to the autobiographical surrealism of Panic Movement compatriot Fernando Arrabal a hook. I do, but while I've read a lot of reviews, some of them quite astute, none seem interested in exploring this facet of Jodorowsky's past.

Luckily for me, there's nothing but history at play with The Metabarons. I've already detailed the premise behind this series, so I'll only repeat that it's a spin-off of The Incal -- that Moebius-drawn saga spiraled outward from the ruins of Dune -- and that it purports to narrate the history of a caste of space warriors whose toughness leaves their children even tougher, yet emotionally deadened. The Dance of Reality, I'm told, frames this father-to-son toughening (also a motif in Jodorowsky films such as El Topo and Santa Sangre) in explicitly autobiographical terms, which is no surprise: Jodorowsky's is an unusually obsessive body of work, incorporating comics, movies, prose, tarot readings, therapeutic role-playing, etc. as different manifestations of the same queries on how best to live as guarantor of pain you couldn't sign for as a child.

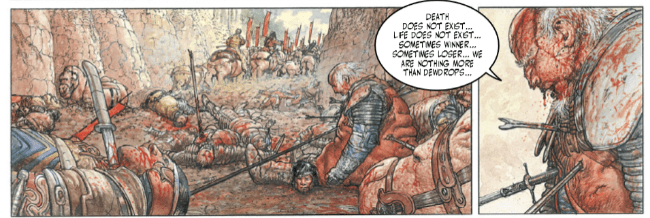

Castaka, however, is a prequel, and thus needn't concern itself so much with solutions. Beginning three generations before the start of The Metabarons (and framed, again, as a story told from one character to another), the plot leaps across a grip of boys' favorite genres in much the same way as its parent title. At first we are presented with jidaigeki – warring clans of ersatz samurai, their banners color-coded as if from Kurasawa's Ran, bound by codes of honor yet capable of most excellent treachery. The tone is that of exoticism, leering and sensational, delighting in its portrayal of departures from morality: a queen, at one point, is plucked from her garden via airship and triumphantly raped in front of her assembled subjects, though she and her rapist, eventually, become fond enough of one another for honorable suicide after the child of violence, the first proto-Metabaron, is brought to term in the face of a society of men rendered totally infertile by bacteriological warfare: purple gas ejaculated onto them from a wall of yellow ceramic pricks.

Paternalistic myth is thus delivered with chop-licking glee, often delving into overt male fantasy – left the only man in the world with functional sperm, the child is raised as a stud to sire the next generation, though he knows no love until a hard woman from far away (“Men are all just vulgar pigs!” is her first spoken line, a sentiment which lasts all of 15 ensuing panels) matches him in combat and bites his shoulder... the only touch that he can remember of his mother! Soon he is wailing like a babe, and the two are commingling open wounds in passion on the floor.

I am unaware of the production process for this book, save that it was originally released as two French albums in 2007 and 2013, but my understanding is that Jodorowsky typically improvises his scenarios piece by piece, based on what his artists have already completed, so I think it's fair to guess that Das Pastoras completed the work essentially "in sequence." An artist active on the European comics scene since the early 1980s, Das Pastoras is often compared to the American likes of Richard Corben, though he also shares certain similarities with the artist for The Metabarons proper, Juan Giménez. Both are painters apt to retaining a core of caricature at the heart of their art, and both are adept at filling the page with noisy, busy activity without sacrificing too much in the way of clarity.

Truthfully, unlike Giménez, Das Pastoras gets off to a rough start with an overly-stiff, pose-y sequence of hand-to-hand combat in the book's opening pages. Intentionally or not, subsequent pages then come to favor large crowds occupying wide spaces, with which the artist seems more comfortable, especially when large, putty-like beasts are involved (which naturally flatters Jodorowsky's own career-spanning fondness for elephants). By the end of Tome 1, isolated bodies-in-motion are drawn with considerably more authenticity of contact, while also offering a certain flair for racial differentiation, which immediately becomes critical to the story.

An alterationist of myth and pulp alike, Jodorowsky is undoubtedly familiar with the seams binding the jidaigeki and the American western. As such, planet and narrative are soon literally invaded by representatives from Jodorowsky's shared universe, the missionary/conqueror Techno-Technos, whose metaphorical opening of “Japan” to the “west” turns on a dime into the disease-spreading influence of European colonists on natives of the Americas, who are soon decimated: recall the froggy conquistadors from The Holy Mountain.

Afterward, the true character of Castaka is revealed: it's another Jodorowsky western, with the grown stud, his warrior wife, and their two borderline-feral daughters becoming intergalactic Indian desperadoes, sacking wagon trains along the trail of stars for profit and revenge. It's hugely energetic stuff, writer and artist now working in perfect synch to render their protagonist as a veritable screaming-mad Klaus Kinski, his features permanently wrought with hot rage, eyes wild and dialogue tending toward “LAMENTABLE TRAITOR!” and other top-of-the-lungs exhortations whilst his growing girls exhibit departures from their writer's offhanded mytho-poetic gender essentialism: one becomes buxom like her mother, while the other is drawn as, basically, a slighter variant on Marvel Comics' Wolverine (on whom Das Pastoras has also worked), though both remain superior fighters, and ultimately conjoin their very bodies(!) to dissolve any distinction between "masculine" and "feminine" personality traits – which, given the eternally boyish outlook of the project's genre apparatus, means they capture a man's sperm before besting him in combat, and there is so much respect when he dies.

This has always been part of Jodorowsky's appeal: he never disguises his taste for the lurid, in fact flaunting it as a means of facilitating spiritual and psychological inquiry. However, Castaka is hamstrung as a commercial work, in an industrial continuum, in that its excitations cannot develop into anything stronger than premonitions as to the direction of its parent narrative. As a result, there are only a few gestures toward the notions of reconciliation and self-abnegation at the heart of The Metabarons – the reason the story there is told from one character to another, after all, is because the receiving character must do something good with that understanding. In here, another Das Pastoras giant animal eventually enters the fray, and its relationship with the roving space family isn't quite respectful so much as an accident of personal codes complimenting one another, which I suppose will have to double for a suggestion of enlightenment divined from a collective unconsciousness lacking, for the moment, in praxis.

Still, if we want to talk text, Castaka is an indefatigable exercise, very well-made once it settles into its revenge narrative groove, and differing from The Metabarons in one crucial generic element: it's about fathers and daughters, and, if anything, I suppose the rank misogyny which Jodorowsky disinters from patriarchal tradition is meant to finally bend its knee before an evolved brand of violence which allows women to kill with total autonomy, without pity. An old exploitation spectacle then, from a proper midnight movie man.