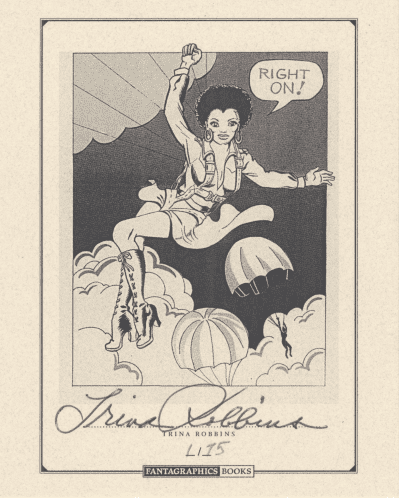

Wimmens Comix’s own Goddess

Trina Robbins, now approaching eighty, warned comics artists and readers a decade or two ago that she was preparing a memoir. Some of them—I should say some of us—wondered or even winced a little. She was famously in the thick of the underground comix world of 1970 to 1980 or so, furious at most of the male artists for their exclusionary mentality, which was closer to Tubby’s “Girl-Haters Club” than the comradely, even leftwing confraternity than they claimed. Her fire has not banked, but Trina has given the readers, some of them comix fans hardly born in the new century, a history of the times that emphatically includes a very remarkable history of herself.

Casual readers flipping through the pages of Last Girl Standing, my own way of reading any book with comic pages, will surely be struck in the early chapters by the contrast between sweet kid-and-teen family photos, and men’s-magazine-Trina in the nude. From early on, she seems to have had more self-confidence than she readily admits, because her outsider status, as a Jewish girl in heavily gentile Queens (with a Reddish or at least pro-Russian dad, for that matter), held her back not at all. She learned to read at age 4. Not long after that, she took up what turned out to be a life-long practice of sewing nearly anything she wanted to do, especially for women friends. We learn a hundred or so pages later that artistic efforts with cloth and with poster-making led to… comics, or comix.

Actually, Trina the comix maven comes in rather late in the picture, which is interesting for many reasons. She was years older than most of the rising u.g. comix artists, although by no means all of them. An advanced youngster in the golden age of comic books, she had drunk in the original Wonder Woman along with many of the lesser imitators. She didn’t realize it right away, but she was a hipster of the 1950s, when in many ways, New York City was at its peak as a world city of stunning architecture, manufacture of fashion garments, and rents low enough for the working class. In photos from the early 1950s, she appears the picture of innocence. Little did she know what was ahead.

By the late 1950s, still in New York, she had already adopted future science fiction giant Harlan Ellison as a boyfriend. Onward to L.A., where another new friend, sci-fi maven Forrest Ackerman, convinced her to become a nude model for men’s magazines. She gave in, she says, out of a feeling that she had no other particular talent. Actually, she was already figuring out what she could do about that. She wandered through the 1960s hanging with the likes of The Byrds, the Mommas and Poppas, and even Jim Morrison of the Doors, never a groupie but definitely On The Scene. And then she came back to New York, where she found her calling, more or less, at the East Village Other. There, her vaunted comics life was launched.

But first, she set up a little boutique, made and sold dresses for hippie chicks but also for the thriving theater scene. She appeared in cameo roles in several of the Andy Warhol films, not to mention assorted counterculture adventures, and she also had flings (as she calls them) with Abbie Hoffman and Paul Krassner. And like so many others of the historic moment, not excluding this reviewer, she smoked a whole lot of dope.

And then comic art, which was still in the process of becoming comix. She and her new boyfriend, Kim Deitch (son of Gene Deitch, famed animator of the 1950s), lived in a sort of comix museum of their own making on East Ninth Street, with art pinned on the walls in front while the two lived in the back. The modish East Village Other, offering up comics, soon produced Gothic Blimp Works, their own tabloid, under the editorship of Vaughan Bode. Whoever was fortunate enough to see a copy on sale or be sent one—somehow, several found their way to me in Wisconsin--had a real visual experience. A wild array of fresh talent suddenly showed itself: Robert Crumb, Justin Green, Jay Lynch, Leslie Carbarga, Art Spiegelman, Gilbert Shelton, Deitch and Trina, to mention only some of them.

About this time, the very end of the 1960s, two things happen to Robbins, one very personal and the other vital to the history of comic art. She decided to have a baby, although partner Kim was hitting the bottle with ever more determination. And she decided to move to the Bay Area, where for all the reasons of the regional cultural explosion, new comic art was also happening. In what might be described as a road trip resembling the drive of Orson Welles to Hollywood in 1940 by a personal chauffeur who later became a major horror film producer, Trina and Kim hopped a ride to San Francisco with Gilbert Shelton. There, as she writes, the approximately periodical comix tabloid Yellow Dog was already appearing, and Zaps were being prepared. They arrived in December, 1969.

Readers of Last Girl Standing, sympathetic both to Trina and to the inner circle of artists producing Zap and a host of other comics in the following decade, will likely find the next section of the book a bit nerve-rattling. She is still very, very angry at the sexual politics of the circle of males around Crumb, being placed among The Wives—if placed at all—and getting restless to produce her own stuff. Out of that anger, must have come some of the energy to produce It Ain’t Me Babe (1971) whose title was taken from a local women’s liberation tabloid of the same name, for which she happened to be an eager volunteer. In the meantime, she drew some very keen, anti-sexist satirical pieces for Denis Kitchen’s Projunior comic, published out in Wisconsin, and settled herself, by 1975, into a Victorian house that she still inhabits today.

It Ain’t Me Babe, the one-shot title, soon became a stunning series of Wimmen’s Comix, later Wimmin’s Comix, collected at last in 2015 as a set. As in any anthological series, the quality of art and narrative vary widely, strip to strip and artist to artist, but the uniqueness of the creation, the degree of keen insights and real humor about what used to be called the “Sex War,” had a major impact. Women’s comic art had, in at least a small way, come of age. Seen generations later, the work of the collective stands up, partly because these comics are good and perhaps also because things have improved less than we would have hoped.

Lamentably, Wimmen’s Comix also presents an opportunity lost in Last Girl Standing. Perhaps it is difficult to talk about one artist or a few artists without leaving out many, or perhaps it is Trina’s difficult leadership role that comes back so vividly to her. The quarrels of women artists versus women artists, Aline Kominsky in particular versus Trina, obviously still sting. The legendary Spain Rodriguez later told Trina that the male artists wanted a little world of their own and Trina’s personal style simply did not fit in. Spain and others worked hard, in future decades, to make up for early deficits. Perhaps the intimacy of the 1970s scene in which a handful of artists, with no ruminative benefits to their work but a whole lot of artistic innovation, made the scene so intense and in a way, exclusionary. Trina was a leader and she created her own comics scene. She also drew some fine comic art of her own, as I recalled when pulling Trina’s comics out of the attic. “Panthea,” “Rosie the Riveter” and other of her characters are lovingly drawn, the stories and art losing none of their energy and drama from forty years ago.

The events of the later 1970s merge into Trina’s life over the next forty years almost seamlessly, as if the main stories have already been told. Wet Satin, the erotic three-issue comic mixing satire and sex, certainly marked one moment in American art history, and like Tits ‘n Clits (produced down in San Diego) helped congeal a set of female friendships at Comic-Cons and elsewhere that has lasted and gone international. She also did Wonder Woman, in one of the mainstream revivals of the iconic figure, later began to produce women’s comics for young adults, and still later edged closer to a different self: the scholar.

Trina almost rushes past a significant history volume on artists, Women and the Comics, republished as A Century of Women Cartoonists followed by From Girls to Grrlz, proving the women had also been readers (and buyers) of comic books. Her work goes on, mainly as a scriptwriter for other artists and notably Anne Timmons but also getting a forgotten memoir by her father, published in Yiddish, translated and published in English, with some comics illustrations. In other words, she goes on. Quite a life, quite an artist.##

Paul Buhle’s latest comic is drawn by Noah Van Sciver: Johnny Appleseed.