In Roughneck, the latest graphic novel from Jeff Lemire, violence begets violence, the sins of the father are visited upon the son, and various other truisms apply. Lemire has returned to rural Ontario, but he’s visiting harsher places than those found in Essex County, his series of understated, beautifully rendered portraits of working-class life. Few of Lemire’s stories in the years since Essex have had the same poignancy, and while the environs of Roughneck are dingier, the book doesn’t cut as deep. Lemire’s lead, Derek Ouelette, is an ex-hockey player and a small-down nuisance. He spends his days drinking and fighting until the reappearance of his sister, an Oxycontin addict with an abusive partner, forces him to face his demons. The book is well intentioned but obvious; it has the ambition of a great work but a fixation on familiar tropes.

Roughneck seeks to examine the effects of violence—how it travels down generations, how violence directed outward also impacts oneself. Derek’s father pushed a toxic notion of manhood on Derek the youth, encouraging an aggressive streak that eventually caused the end of Derek’s NHL career. Derek spends his life after hockey being provoked and lashing out, again and again. It’s worthwhile subject matter, and the book would be a welcome addition to the literature of masculinities—especially given Lemire’s parallel career as a writer of superhero books, a comics tradition that tends to depict violence without so much ambivalence. But from beginning to end, Roughneck is too formulaic to shake up anyone’s preconceptions.

The success of a work like this—one that tackles big topics or interrogates received wisdom—sometimes depends on small, even incidental details as much as anything else. That’s a cliché in its own right, but the missteps of Roughneck validate the idea. The book’s dialogue, rather than enhancing readers’ sense of place, character, or history, reads as if borrowed from films or TV shows with similar concerns. When Derek enters a liquor store by saying, “Need to pick up my prescription,” for instance, the line establishes him more as a stock figure than a fully realized creation.

Scenes involving Derek’s father are worse. “You come to blame me for all your bullshit?” the old man says during a climactic confrontation with Derek’s sister. “Well, boo-hoo. We all got shit to deal with, kid.” Her reply includes: “'You're scared of everything. Scared of dying. Scared of being weak. So you gotta hit and hurt everything around to you to prove how tough you are.” A reader believing in the basic truth of these words—that patterns of violence begin out of fear, that violence rarely reflects strength of character—might nonetheless wince at the scene. It’s the danger of an artist being right while also being derivative. The lines reduce their subject to the stuff of melodrama and limit the persuasive power of the work.

Scenes involving Derek’s father are worse. “You come to blame me for all your bullshit?” the old man says during a climactic confrontation with Derek’s sister. “Well, boo-hoo. We all got shit to deal with, kid.” Her reply includes: “'You're scared of everything. Scared of dying. Scared of being weak. So you gotta hit and hurt everything around to you to prove how tough you are.” A reader believing in the basic truth of these words—that patterns of violence begin out of fear, that violence rarely reflects strength of character—might nonetheless wince at the scene. It’s the danger of an artist being right while also being derivative. The lines reduce their subject to the stuff of melodrama and limit the persuasive power of the work.

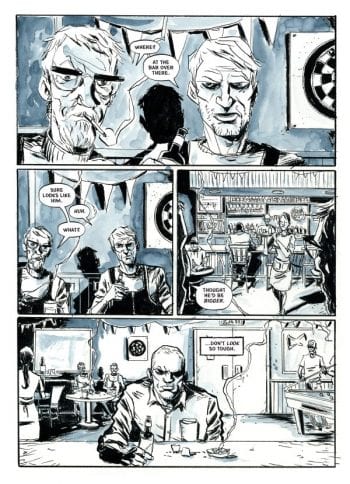

Lemire takes more risks with visual and literary devices throughout Roughneck, but his success rate is not much higher. Flashbacks unfold in full color, while present-day scenes have a subdued blue wash—a simple and effective contrast between Derek’s muted, melancholy status quo and other stages of his life. Other choices feel more like manipulation, e.g. the impossibly sad-eyed dog that appears before Derek from time to time, symbolizing unconfronted baggage. Lemire is trying here, but the story never achieves a meaningful depth of characterization through the various devices at work. Derek is a typical tortured tough guy, and his quiet desperation reads as much like the book’s pop-culture inheritance as the character’s family inheritance.

Readers also learn in the course of Roughneck that Derek and Beth’s mother was a member of the Cree First Nations group—a detail Lemire handles with respect but also seemingly with such a mind to his outsider status that mentions of the siblings’ mixed heritage appear in a limited and somewhat remote way. It’s difficult not to register a racial dimension to a scene in which Derek and Beth’s white father abuses their Cree mother, for example, but Roughneck doesn’t really have the tools to pursue the implications.

Lemire’s compositional gifts are a saving grace of the book, as they have been with certain other works post-Essex County. Spot blacks anchor his pages, scratchy linework complements the setting’s brittle cold, and he’s a clear, confident depicter of movement. Even so, a number of scenes call out for more adventurous—or at least more surprising—visual storytelling. When Derek and Beth catch up after a years-long estrangement, panels trade off points of view as if Lemire were cutting between camera setups. And a three-page montage of Derek frying eggs at a restaurant job reads less like the book exploring the tedium of his days and more like the book marking the time.

Lemire’s compositional gifts are a saving grace of the book, as they have been with certain other works post-Essex County. Spot blacks anchor his pages, scratchy linework complements the setting’s brittle cold, and he’s a clear, confident depicter of movement. Even so, a number of scenes call out for more adventurous—or at least more surprising—visual storytelling. When Derek and Beth catch up after a years-long estrangement, panels trade off points of view as if Lemire were cutting between camera setups. And a three-page montage of Derek frying eggs at a restaurant job reads less like the book exploring the tedium of his days and more like the book marking the time.

There are glimpses of a better story within Roughneck. One early scene finds teenage hockey players asking Derek for a selfie, having watched his (literal) greatest hits on YouTube. Before the sequence descends into violence—including a corny, Sin City-style splash of red upon the blue pallet—the discomfort on display is more distinct, more specific to the situation, than most other sensations in the story. Later, in the aftermath of Derek assaulting drug dealers because Beth has overdosed, the siblings, a sympathetic cop, and a family friend discuss next steps. Throughout their conversation, every small complication matters to the characters. It’s a refreshing change in a book that works mainly with large signposts.

Roughneck rejects violence as a solution to life’s obstacles, but it works with a heavy hand. Might doesn’t make right. Big doesn’t mean profound either. And although Roughneck has the trappings of a comics masterpiece, it never finds its own story to tell.