Inés Estrada is a 26-year-old Mexican cartoonist currently living in the USA. According to her blog , she makes a living “making whatever the fuck I want,” and that includes self-publishing Impatience, a beautifully printed and designed book. The cover is outlined in intense red which carries over to the edges of the pages and the back cover, which is printed in silver ink on a red background. Impatience is an anthology that includes comics in English and comics in Spanish featuring simultaneous translation into English.

“Traducciones” (“Translations”) is one of the translated stories. Estrada handles translating her own work in an unusual way—instead of replacing the original Spanish language balloons with English, as is usually done with translated comics, she places the translation at the bottom of the page, typeset with slashes to indicate a new balloon or caption. It is easier to read than you might expect—no more difficult than watching a movie with subtitles. Easier even—you don’t have to read them in a hurry like you do with movie subtitles or opera surtitles. It also means that the translation doesn’t have to be in any way abridged. I’ve only seen this before in poetry books. As an undergraduate I read Pablo Neruda’s Twenty Love Songs and a Song of Despair in parallel translation. The Spanish original poem would be on the left-hand page and the English translation on the right.

The obvious advantage of this kind of translation is that an artist avoids many of the compromises one must make when translating in the word balloons and captions. Not only do you lose the original language when you re-letter the balloons, but whatever phrases you replace them with must be made to fit into the old balloons. With Impatience and Lapsos, you can read Estrada’s original words and her own translation of them. But it does mean that the reader’s eyes are always bouncing up and down the page in order to take it in.

The main character in “Traducciones” is Lucía who works as a freelance translator of medical and academic documents. She is in love with a man named Felipe (who lives in Chile) and sleeps with a man named Foco whom she doesn’t like. Lucía has strange dreams. In one dream, she finds her house infested with “cockroach mice” and follows them into a small dark portal which takes her into another world. This ends up being a common occurrence in Estrada’s stories. It happens in the wordless story “Cenote” (the title of which refers to naturally occurring ponds in the Yucatan that were often used by Mayans as sacred sites). In “Cenote,” the portal is the protagonist’s own vagina. Travelling through tiny portals to parallel dimensions happens repeatedly in Estrada’s graphic novel Lapsos.

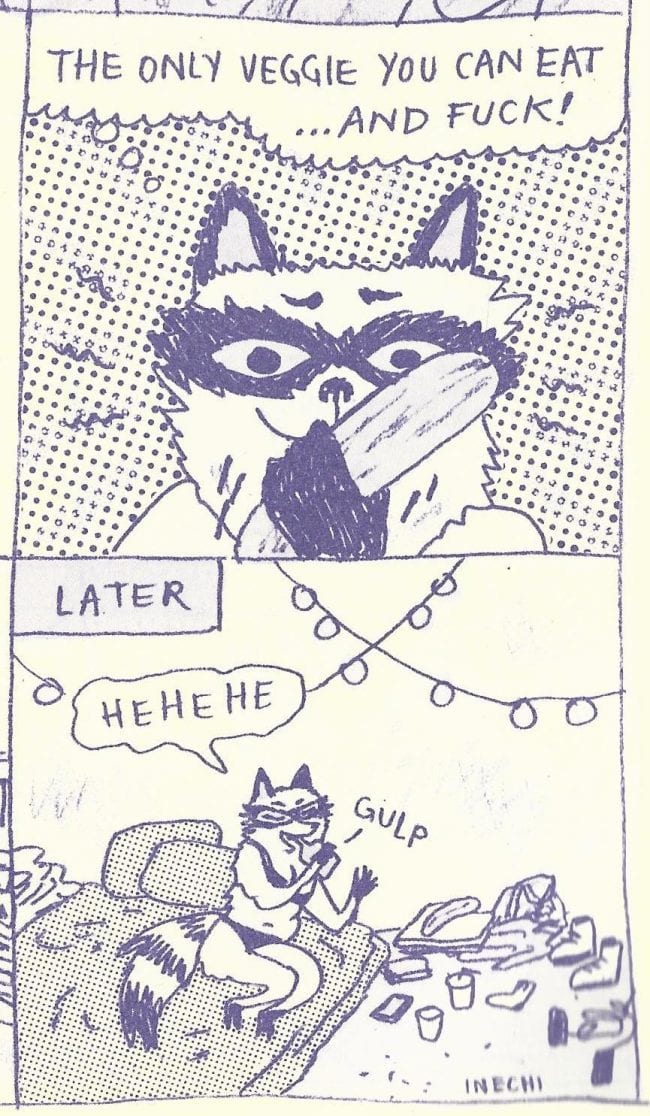

As “Cenote” suggests, Estrada is not afraid of sexuality and the body as subject matter. “Skunk Girl” is the story of a young woman who has since childhood had a disgusting smell. She finally learns to suppress and control it with mind-power, but she finds it sometimes useful to turn on—to make herself smell bad to dangerous people, but to also to lovers who happen to find that smell a turn-on. “Pachecomics” is an anthropomorphic strip featuring a turtle named Moco, a cat named Akram and a raccoon named Tencha. In one episode, Tencha buys a cucumber, “The only veggie you can east . . . and fuck!” She does use the cucumber as a dildo but it breaks off in her vagina. Her protagonists are usually young women who are horny and on the prowl for “hot boys.” Her frankness and her drawing remind me a little of early Julie Doucet.

Her subject matter revolves around hard partying young people in Mexico City—lots of drinking, pot-smoking and punk rock. One story, “Sindicalismo #89”, seems particularly anchored in a real place. The title refers to an address of a shabby apartment building and the people who live in it, including (not surprisingly) two young hard-partying women, Pau and Mecha. In her interview with Greg Hunter, she said that she used to live there, but the story was “not autobiographical at all.”

Lapsos (“Lapses” in English) was originally published in 2014, but a new edition by Spanish publisher Ediciones Valientes was published in September of this year. As with “Traducciones” and many of the other stories in Impatience, Lapsos features a simultaneous translation.

Lapsos (“Lapses” in English) was originally published in 2014, but a new edition by Spanish publisher Ediciones Valientes was published in September of this year. As with “Traducciones” and many of the other stories in Impatience, Lapsos features a simultaneous translation.

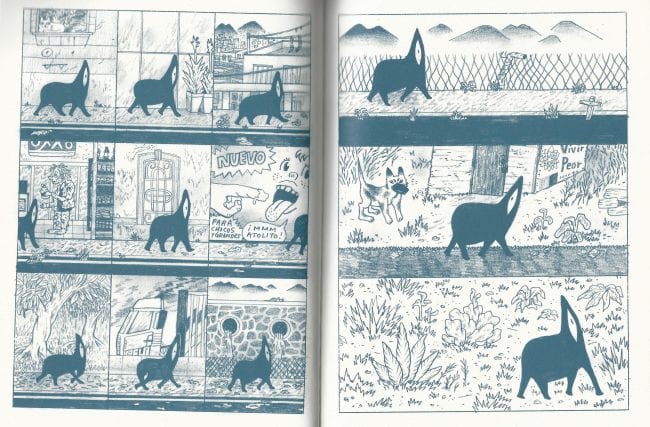

The story starts off with several germ-like entities having an encounter that seems simultaneously sexual and like a shared drug experience. It lets you know right away that you aren’t entering a naturalistic story, but it launches quickly into a more-or-less realistic story about the main character, a semi-irresponsible young man named Roque. This is makes it distinct from the stories in Impatience which invariably feature female protagonists. Roque has a job as a bus-driver (which he only got because he was the grandson of someone his boss really respected); he is separated from Ceci who he got pregnant in high-school—they have a son named Cometa—and like the typical Estrada protagonist, he likes drinking beer, getting high and going with his purely platonic female roommate Mayra to see punk rock bands. Things start getting weird for Roque when he runs over a two-headed Siamese cat. The cat who appears in his dreams making weird, unpleasant music.

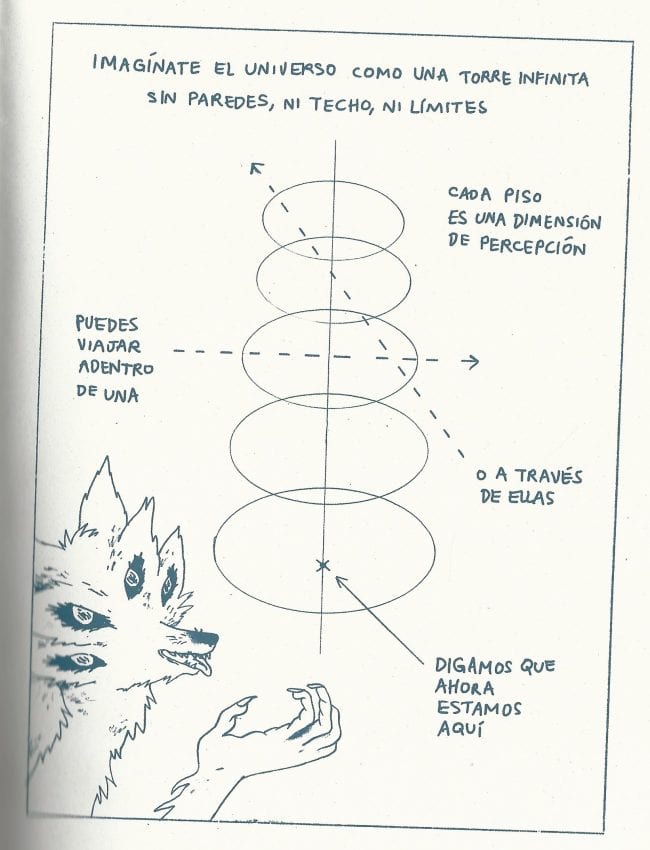

That sound is also made when a one-eyed denizen of another dimension finds a “monochord”, a musical instrument that when played opens a door to our dimension. One-eye comes through the portal here while Roque and Mayra are simultaneously sucked into another dimension. Roque and Mayra have numerous adventures traveling from dimension to dimension. In each dimension, they encounter strange creatures, including a four-eyed wolf-like critter that explains to them how the dimensions work and how to travel from one to another.

Meanwhile, in our dimension, the one-eyed creature encounters Cometa, who mistakes it for a cat, and Roque’s grandmother, who thinks he may be death coming for her (the creature is a black shape). He finds these encounters with the “biclops” disturbing and heads out of the city into the wilderness to avoid them. Roque and Mayra hear the song of the two-headed cat and use that music to reenter our universe through the body of the one-eyed creature. They end up far from the city where they find a new appreciation for our world, especially in its natural forms.

Lapsos doesn’t add up to much in the end. It’s best seen as a series of bizarre adventures along with some flashback to Roque, Mayra and Ceci’s school days. But Estrada’s art is excellent—the book is printed in blue ink (except for a certain number of duotine pages), and the drawing seems to combine pencil and ink. It is pleasingly hand-made and her designs for the extradimensional creatures are simple and effective.

Impatience is the more satisfying of the two books—each little story packs its own punch in a way that you don’t get with Lapsos, even though they overlap quite a bit in subject matter. The story in Lapsos doesn’t feel like it requires a whole book to tell. But the art—the design of the characters, the expressive style Estrada employs, the imaginative page layouts—is stronger in Lapsos. It has a visual unity that Impatience, by virtue of it having been published over the course of 3 years in a wide variety of formats, lacks. Both books are excellent in their own ways.